ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Only 38 % of young adults with hypertension have controlled blood pressure. Lifestyle education is a critical initial step for hypertension control. Previous studies have not assessed the type and frequency of lifestyle education in young adults with incident hypertension.

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this study was to determine patient, provider, and visit predictors of documented lifestyle education among young adults with incident hypertension.

DESIGN

We conducted a retrospective analysis of manually abstracted electronic health record data.

PARTICIPANTS

A random selection of adults 18–39 years old (n = 500), managed by a large academic practice from 2008 to 2011 and who met JNC 7 clinical criteria for incident hypertension, participated in the study.

MAIN MEASURES

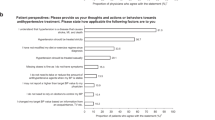

The primary outcome was the presence of any documented lifestyle education during one year after meeting criteria for incident hypertension. Abstracted topics included documented patient education for exercise, tobacco cessation, alcohol use, stress management/stress reduction, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, and weight loss. Clinic visits were categorized based upon a modified established taxonomy to characterize patients’ patterns of outpatient service. We excluded patients with previous hypertension diagnoses, previous antihypertensive medications, or pregnancy. Logistic regression was used to identify predictors of documented education.

KEY RESULTS

Overall, 55 % (n = 275) of patients had documented lifestyle education within one year of incident hypertension. Exercise was the most frequent topic (64 %). Young adult males had significantly decreased odds of receiving documented education. Patients with a previous diagnosis of hyperlipidemia or a family history of hypertension or coronary artery disease had increased odds of documented education. Among visit types, chronic disease visits predicted documented lifestyle education, but not acute or other/preventive visits.

CONCLUSIONS

Among young adults with incident hypertension, only 55 % had documented lifestyle education within one year. Knowledge of patient, provider, and visit predictors of education can help better target the development of interventions to improve young adult health education and hypertension control.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, Minino AM, Kung HC. Deaths: preliminary data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;59:1–51.

Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–50.

Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:e28–e292.

Yoon PW, Gillespie CD, George MG, Wall HK. Control of hypertension among adults—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2005-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:19–25.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72.

James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507–20.

Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:14–26.

Appel LJ, Brands MW, Daniels SR, Karanja N, Elmer PJ, Sacks FM. Dietary approaches to prevent and treat hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2006;47:296–308.

Mattila R, Malmivaara A, Kastarinen M, Kivela SL, Nissinen A. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention for hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:199–205.

Miller ER 3rd, Erlinger TP, Young DR, et al. Results of the Diet, Exercise, and Weight Loss Intervention Trial (DEW-IT). Hypertension. 2002;40:612–8.

Whelton SP, Chin A, Xin X, He J. Effect of aerobic exercise on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:493–503.

Ketola E, Sipila R, Makela M. Effectiveness of individual lifestyle interventions in reducing cardiovascular disease and risk factors. Ann Med. 2000;32:239–51.

Ardery G, Carter BL, Milchak JL, et al. Explicit and implicit evaluation of physician adherence to hypertension guidelines. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2007;9:113–9.

Bell RA, Kravitz RL. Physician counseling for hypertension: what do doctors really do? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:115–21.

Booth AO, Nowson CA. Patient recall of receiving lifestyle advice for overweight and hypertension from their General Practitioner. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:8.

Egede LE, Zheng D. Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in adults with diabetes: prevalence and missed opportunities for physician counseling. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:427–33.

Heymann AD, Gross R, Tabenkin H, Porter B, Porath A. Factors associated with hypertensive patients' compliance with recommended lifestyle behaviors. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13:553–7.

Mellen PB, Palla SL, Goff DC Jr, Bonds DE. Prevalence of nutrition and exercise counseling for patients with hypertension. United States, 1999 to 2000. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:917–24.

Moeller MA, Snelling AM. Health professionals' advice to Iowa adults with hypertension using the 2002 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Health Promot. 2006;20:392–5.

Valderrama AL, Tong X, Ayala C, Keenan NL. Prevalence of self-reported hypertension, advice received from health care professionals, and actions taken to reduce blood pressure among US adults—HealthStyles, 2008. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:784–92.

Viera AJ, Kshirsagar AV, Hinderliter AL. Lifestyle modification advice for lowering or controlling high blood pressure: who's getting it? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2007;9:850–8.

Tsiantou V, Pantzou P, Pavi E, Koulierakis G, Kyriopoulos J. Factors affecting adherence to antihypertensive medication in Greece: results from a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2010;4:335–43.

Fenton JJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, Ciechanowski P, Young BA. Quality of preventive care for diabetes: effects of visit frequency and competing demands. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:32–9.

Zulman DM, Kerr EA, Hofer TP, Heisler M, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Patient-provider concordance in the prioritization of health conditions among hypertensive diabetes patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:408–14.

Jaén CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1994;38:166–71.

Hatahet MA, Bowhan J, Clough EA. Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality (WCHQ): lessons learned. WMJ. 2004;103:45–8.

Sheehy A, Pandhi N, Coursin DB, et al. Minority status and diabetes screening in an ambulatory population. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1289–94.

Thorpe CT, Flood GE, Kraft SA, Everett CM, Smith MA. Effect of patient selection method on provider group performance estimates. Med Care. 2011;49:780–5.

Myers MG, Tobe SW, McKay DW, Bolli P, Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA. New algorithm for the diagnosis of hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1369–74.

Schmittdiel J, Selby JV, Swain B, et al. Missed opportunities in cardiovascular disease prevention?: low rates of hypertension recognition for women at medicine and obstetrics-gynecology clinics. Hypertension. 2011;57:717–22.

Johnson HM, Thorpe CT, Bartels CM, et al. Undiagnosed hypertension among young adults with regular primary care use. J Hypertens. 2014;32:65–74.

Tu K, Campbell NR, Chen ZL, Cauch-Dudek KJ, McAlister FA. Accuracy of administrative databases in identifying patients with hypertension. Open Med. 2007;1:e18–26.

Manson JM, McFarland B, Weiss S. Use of an automated database to evaluate markers for early detection of pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:180–7.

Gearing RE, Mian IA, Barber J, Ickowicz A. A methodology for conducting retrospective chart review research in child and adolescent psychiatry. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15:126–34.

Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Matchar DB, Reichert TA. Regression models for prognostic prediction: advantages, problems, and suggested solutions. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985;69:1071–77.

Scheuner MT, Wang SJ, Raffel LJ, Larabell SK, Rotter JI. Family history: a comprehensive genetic risk assessment method for the chronic conditions of adulthood. Am J Med Genet. 1997;71:315–24.

Fluker SA, Whalen U, Schneider J, et al. Incorporating performance improvement methods into a needs assessment: experience with a nutrition and exercise curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:S627–33.

Murff HJ, Rothman RL, Byrne DW, Syngal S. The impact of family history of diabetes on glucose testing and counseling behavior in primary care. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2247–8.

Reisch LM, Fosse JS, Beverly K, et al. Training, quality assurance, and assessment of medical record abstraction in a multisite study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:546–51.

Borzecki AM, Wong AT, Hickey EC, Ash AS, Berlowitz DR. Identifying hypertension-related comorbidities from administrative data: what's the optimal approach? Am J Med Qual. 2004;19:201–6.

Hebert PL, Geiss LS, Tierney EF, Engelgau MM, Yawn BP, McBean AM. Identifying persons with diabetes using Medicare claims data. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:270–7.

Marciniak MD, Lage MJ, Dunayevich E, et al. The cost of treating anxiety: the medical and demographic correlates that impact total medical costs. Depress Anxiety. 2005;21:178–84.

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27.

Fawcett J, Kravitz HM. Anxiety syndromes and their relationship to depressive illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983;44:8–11.

Starfield B, Weiner J, Mumford L, Steinwachs D. Ambulatory care groups: a categorization of diagnoses for research and management. Health Serv Res. 1991;26:53–74.

Mitsnefes MM. Hypertension in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:493–512.

Milder IE, Blokstra A, de Groot J, van Dulmen S, Bemelmans WJ. Lifestyle counseling in hypertension-related visits--analysis of video-taped general practice visits. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:58.

Bertakis KD, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Azari R, Robbins JA. The influence of gender on physician practice style. Med Care. 1995;33:407–16.

Henderson JT, Weisman CS. Physician gender effects on preventive screening and counseling: an analysis of male and female patients' health care experiences. Med Care. 2001;39:1281–92.

Schmittdiel J, Grumbach K, Selby JV, Quesenberry CP Jr. Effect of physician and patient gender concordance on patient satisfaction and preventive care practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:761–9.

Piette JD, Kerr EA. The impact of comorbid chronic conditions on diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:725–31.

Krein SL, Hofer TP, Holleman R, Piette JD, Klamerus ML, Kerr EA. More than a pain in the neck: how discussing chronic pain affects hypertension medication intensification. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:911–6.

Rand CM, Auinger P, Klein JD, Weitzman M. Preventive counseling at adolescent ambulatory visits. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:87–93.

Stange KC, Woolf SH, Gjeltema K. One minute for prevention: the power of leveraging to fulfill the promise of health behavior counseling. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:320–3.

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012:1–8.

Yarnall KS, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Family physicians as team leaders: “time” to share the care. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A59.

Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Smith TF, et al. How valid are medical records and patient questionnaires for physician profiling and health services research? A comparison with direct observation of patients visits. Med Care. 1998;36:851–67.

Stange KC, Flocke SA, Goodwin MA, Kelly RB, Zyzanski SJ. Direct observation of rates of preventive service delivery in community family practice. Prev Med. 2000;31:167–76.

Galuska DA, Will JC, Serdula MK, Ford ES. Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? JAMA. 1999;282:1576–8.

Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Physician counseling about exercise. JAMA. 1999;282:1583–8.

Acknowledgements

Contributors

The authors gratefully acknowledge Patrick Ferguson and Katie Ronk for data preparation, and Colleen Brown for manuscript preparation.

Funders

Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the Health Innovation Program and the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) under award number UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health under award number U54TR000021. Heather Johnson is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23HL112907, and also by the University of Wisconsin Centennial Scholars Program of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Amy Kind is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number K23AG034551, the American Federation for Aging Research, the Atlantic Philanthropies, the Starr Foundation, and the Madison VA Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center. Nancy Pandhi is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under award number K08AG029527. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional funding for this project was provided by the University of Wisconsin Health Innovation Program and the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health from the Wisconsin Partnership Program.

Prior Presentations

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, H.M., Olson, A.G., LaMantia, J.N. et al. Documented Lifestyle Education Among Young Adults with Incident Hypertension. J GEN INTERN MED 30, 556–564 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3059-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3059-7