Abstract

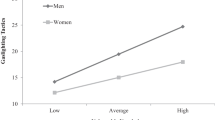

Intimate partner violence (IPV) has been associated with adverse physical, psychoemotional, and sexual health, and African American women are at higher risk for experiencing IPV. Considering African American women predominantly have African American male partners, it is essential to identify factors associated with IPV perpetration among African American men. The present study examined attitudes toward IPV, ineffective couple conflict resolution, exposure to neighborhood violence, and the interplay of these factors as predictors of IPV perpetration. A community sample of 80 single, heterosexual, African American men between 18 and 29 years completed measures assessing sociodemographics, attitudes towards IPV, perceived ineffective couple conflict resolution, exposure to neighborhood violence, and IPV perpetration during the past 3 months. Hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses, with age, education, and public assistance as covariates, were conducted on 65 men who reported being in a main relationship. Couple conflict resolution and exposure to neighborhood violence moderated the relation between attitudes supporting IPV and IPV perpetration. Among men who reported high ineffective couple conflict resolution and high exposure to neighborhood violence, IPV perpetration increased as attitudes supporting IPV increased. The findings indicated that interpersonal- and community-level factors interact with individual level factors to increase the risk of recent IPV perpetration among African American men. While IPV prevention should include individual-level interventions that focus on skills building, these findings also highlight the importance of couple-, community-, and structural-level interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Atlanta, GA: CDC, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control;2003.

Seth P, Raiford JL, Robinson L, Wingood GM. Intimate partner violence and other partner-related factors: correlates of sexually transmissible infections and risky sexual behaviours among young adult African American women. Sex Heal. 2010; 7: 25–30.

Raiford JL, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM. Effects of fear of abuse and possible STI acquisition on the sexual behavior of African American adolescent girls and young women. Am J Public Health. 2009; 99(6): 1067–1071.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Definition of intimate partner violence. 2009; http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/intimatepartnerviolence/definitions.html. Accessed March 17, 2009.

Edwards V, Black M, Dhingra S, McKnight-Eily L, Perry G. Physical and sexual intimate partner violence and reported serious psychological distress in the 2007 BRFSS. International Journal of Public Health. 2009; 54: 37–42.

Hien D, Ruglass L. Interpersonal partner violence and women in the United States: an overview of prevalence rates, psychiatric correlates and consequences and barriers to help seeking. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2009; 32: 48–55.

Campbell R, Lichty LF, Sturza M, Raja S. Gynecological health impact of sexual assault. Res Nurs Heal. 2006; 29: 399–413.

Bradley R, Schwartz AC, Kaslow NJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among low-income African-American women with a history of intimate partner violence and suicidal behaviors: self-esteem, social support, and religious coping. J Trauma Stress. 2005; 18: 685–696.

Wu E, El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, Chang M. Intimate partner violence and HIV risk among urban minority women in primary health care settings. AIDS Behav. 2003; 7(3): 291–301.

Bauer HM, Gibson P, Hernandez M, Kent C, Klausner J, Bolan G. Intimate partner violence and high-risk sexual behaviors among female patients with sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 2002; 29(7): 411–416.

Gielen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JG, Mahoney P, McDonnell KA, O’Campo P. HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007; 8: 178–198.

Lichtenstein B. Domestic violence, sexual ownership, and HIV risk in women in the American deep south. Social Science & Medicine. 2005; 60(4): 701–714.

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2003.

Stith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: a meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004; 10: 65–98.

Lawoko S. Predictors of attitudes toward intimate partner violence: a comparative study of men in Zambia and Kenya. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008; 23: 1056–1074.

Moore TM, Stuart GL. A review of the literature on masculinity and partner violence. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2005; 6(1): 46–61.

Saunders DG, Lynch AB, Grayson M, Linz D. The inventory of beliefs about wife beating: the construction and initial validation of a measure of beliefs and attitudes. Violence and Victims. 1987; 2: 39–57.

Shields NM, McCall GJ, Hanneke CR. Patters of family and nonfamily violence: violent husbands and violent men. Violence and Victims. 1988; 3: 83–97.

Cadsky O, Crawford M. Establishing batterer typologies in a clinical sample of men who assault their female partners. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 1988; 7: 119–127.

Caetano R, Cunradi CB, Schafer J, Clark CL. Intimate partner violence and drinking among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the US. J Subst Abus. 2000; 11: 123–138.

Cunradi CB, Caetano R, Clark CL, Schafer J. Neighborhood poverty as a predictor of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States: Multilevel analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2000; 10: 297–308.

Cornelius TL, Resseguie N. Primary and secondary prevention programs for dating violence: a review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2007; 12: 364–375.

Riggs D, O’Leary K, Breslin F. Multiple correlates of physical aggression in dating couples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1990; 5: 61–73.

Riggs D, O’Leary K. A theoretical model of courtship aggression. In: Pirog-Good MA, Stets JE, eds. Violence in dating relationships. New York: Praeger; 1989: 53–71.

Antonio T, Hokoda A. Gender variations in dating violence and positive conflict resolution among Mexican adolescents. Violence and Victims. 2009; 24: 533–545.

Robertson K, Murachver T. Attitudes and attributions associated with female and male partner violence. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2009; 39: 1481–1512.

Feldman CM, Ridley CA. The role of conflict-based communication responses and outcomes in male domestic violence toward female partners. J Soc Pers Relat. 2000; 17: 552–573.

Kurdek LA. Conflict resolution styles in gay, lesbian, heterosexual nonparent, and heterosexual parent couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994; 56: 705–722.

Gottman JM, Krokoff LJ. Marital interaction and satisfaction: a longitudinal view. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989; 57: 47–52.

Snyder DK. Manual for the marital satisfaction inventory.: Western Psychological Services; 1981.

Christensen A. Dysfunctional interaction patterns in couples. In: Knoller P, Fitzpatrick MA, eds. Perspectives on marital interaction. Philadelphia: Multilingual Matters; 1988: 31–52.

Toro-Alfonso J, Rodriguez-Madera S. Domestic violence in Puerto Rican gay male couples: perceived prevalence, intergenerational violence, addictive behaviors, and conflict resolution skills. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004; 19: 639–654.

Norlander B, Eckhardt C. Anger, hostility, and male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005; 25: 119–152.

Raghavan C, Rajah V, Gentile K, Collado L, Kavanagh AM. Community violence, social support networks, ethnic group differences, and male perpetration of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009; 24: 1615–1632.

Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Harris TR. Neighborhood characteristics as predictors of male to female and female to male partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009:1–24.

Goldstein PJ. The drug/violence nexus: a tripartite conceptual framework. Journal of Drug Issues. 1985; 15: 493–506.

Ross CE, Jang SJ. Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: the buffering role of social ties with neighbors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2000; 28: 401–420.

Gelles RJ. Family violence. Annu Rev Sociol. 1985; 11: 347–367.

Price EL, Byers ES. The attitudes towards dating violence scales: development and initial validation. Journal of Family Violence. 1999; 14(4): 351–375.

Ewart CK, Suchday S. Discovering how urban poverty and violence affect health: development and validation of a neighborhood stress index. Heal Psychol. 2002; 21(3): 254–262.

Shepard MF, Campbell JA. The abusive behavior inventory: a measure of psychological and physical abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1992; 7: 291–305.

Raj A, Santana C, La Marche A, Amaro H, Cranston K, Silverman JG. Perpetration of intimate partner violence associated with sexual risk behaviors among young adult men. Am J Public Health. 2006; 96(10): 1873–1878.

Silverman JG, Decker MR, Kapur NA, Gupta J, Raj A. Violence against wives, sexual risk and sexually transmitted infection among Bangladeshi men. Sex Transm Infect. 2007; 83(3): 211–215.

Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1983.

Holmbeck GN. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002; 27(1): 87–96.

Stueve A, O’Donnell L. Urban young women’s experiences of discrimination and community violence and intimate partner violence. Journal of Urban Health. 2008; 85: 386–401.

Raghavan C, Mennerich A, Sexton E, James S. Community violence and its direct, indirect, and mediating effects on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2006; 12: 1–18.

Messinger AM, Davidson LL, Rickert VI. IPV among adolescent reproductive health patients: the role of relationship communication. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011; 26(9): 1851–1867.

Bell KM, Naugle AE. Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: moving towards a contextual framework. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008; 28(7): 1096–1107.

Casenave NA, Straus MA. Race, class network embeddedness, and family violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the U.S. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, eds. Physical violence in American families: risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 1990:321–335.

Blankenship KM, Friedman SR, Dworkin S, Mantell JE. Structural interventions: concepts, challenges and opportunities for research. J Urban Health. 2006; 83(1): 59–72.

Higgins JA. Rethinking gender, heterosexual men, and women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2010; 100(3): 435–445.

Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006; 368: 1973–1983.

Tourangeau R, Smith TW. Asking sensitive questions: the impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1996; 60: 275–304.

Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998; 280: 867–873.

Wingood GM, Seth P, DiClemente RJ, Robinson LS. Association of sexual abuse with incident high-risk human papillomavirus infection among young African American women. Sex Transm Dis. 2009; 36: 784–786.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Education & Behavior. 2000; 27(5): 539–565.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raiford, J.L., Seth, P., Braxton, N.D. et al. Interpersonal- and Community-Level Predictors of Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration among African American Men. J Urban Health 90, 784–795 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-012-9717-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-012-9717-3