Abstract

The influence of Fe speciation on the decomposition rates of N2O over Fe–ZSM-5 catalysts prepared by Chemical Vapour Impregnation were investigated. Various weight loadings of Fe–ZSM-5 catalysts were prepared from the parent zeolite H-ZSM-5 with a Si:Al ratio of 23 or 30. The effect of Si:Al ratio and Fe weight loading was initially investigated before focussing on a single weight loading and the effects of acid washing on catalyst activity and iron speciation. UV/Vis spectroscopy, surface area analysis, XPS and ICP-OES of the acid washed catalysts indicated a reduction of ca. 60% of Fe loading when compared to the parent catalyst with a 0.4 wt% Fe loading. The TOF of N2O decomposition at 600 °C improved to 3.99 × 103 s−1 over the acid washed catalyst which had a weight loading of 0.16%, in contrast, the parent catalyst had a TOF of 1.60 × 103 s−1. Propane was added to the gas stream to act as a reductant and remove any inhibiting oxygen species that remain on the surface of the catalyst. Comparison of catalysts with relatively high and low Fe loadings achieved comparable levels of N2O decomposition when propane is present. When only N2O is present, low metal loading Fe–ZSM-5 catalysts are not capable of achieving high conversions due to the low proximity of active framework Fe3+ ions and extra-framework ɑ-Fe species, which limits oxygen desorption. Acid washing extracts Fe from these active sites and deposits it on the surface of the catalyst as FexOy, leading to a drop in activity. The Fe species present in the catalyst were identified using UV/Vis spectroscopy and speculate on the active species. We consider high loadings of Fe do not lead to an active catalyst when propane is present due to the formation of FexOy nanoparticles and clusters during catalyst preparation. These are inactive species which lead to a decrease in overall efficiency of the Fe ions and consequentially a lower TOF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a highly potent greenhouse gas, having a global warming potential of roughly 300, therefore the effect on the atmosphere is far more devastating than carbon dioxide [1,2,3]. N2O is produced by both natural and anthropogenic sources [4,5,6]. There are many sources of anthropogenic N2O such as sewage treatment, fuel and biomass combustion, industrial chemical processes, and contributions from the agriculture sector [4]. Agricultural processes lead to around 60% of the global emissions. The main industrial processes that lead to the formation of N2O such as adipic and nitric acid production [1], with adipic acid production leading to around 80% of the global industrial emission of N2O (~ 10% total) [6, 7]. There are also small industrial uses such as hospital and dental surgeries [8]. Therefore it is extremely important to decompose N2O before it is released into the atmosphere. Decomposition of N2O takes place through dissociation into O2 and N2 (Eq. 1, [9, 10]).

There are many types of catalysts that can be used for N2O decomposition including perovskites [11,12,13,14,15], ceria-based catalysts [16,17,18], spinels [19,20,21] and iron containing zeolites [22]. In the latter case, H-ZSM-5 has been frequently used as a support [23,24,25]. Xie et al. reported 100% conversion at 450 °C using 7.46 wt % Fe [26] while Wood and co-workers [27] reported 84% conversion at 500 °C using an Fe/ZSM-5 catalyst with a loading of 0.57 wt%. Sobalik et al. showed that when using Ferrierite (FER) a Si:Al ratio of 8.5 outperformed Si:Al 10.5 when the same Fe loading is prepared for N2O decomposition [28]. Rauscher et al. reported that low Si:Al ratios are more effective for N2O decomposition catalysts [23]. Fe–ZSM-5 (Si:Al = 11.4) exhibited 95% conversion of N2O at 500 °C in contrast to Fe-BEA (93) achieving just 20% conversion of N2O at 575 °C [29]. The work of both these groups show that Si/Al ratio is an important factor for activity of an N2O decomposition catalyst.

Furthermore, it was shown that zeolites with different framework structures can be used for the decomposition of N2O with MFI (ZSM-5), beta (BEA) and ferrierite (FER) zeolites acting as supports for Fe [29,30,31]. Jisa et al. reported that low loaded Fe-FER was the most active, achieving 85% conversion at 450 °C [32]. FER had the lowest Si/Al ratio (8.6) out of all the zeolites tested compared to 15.5 for BEA and 13.4 for MFI. Supporting the earlier findings that a low Si:Al ratio is necessary for high N2O conversion. As the active Fe site is considered to form on the Al moiety in the zeolite framework, low Si:Al ratio zeolites can facilitate a higher concentration of active species [26].

The rate-limiting step in the decomposition of N2O is typically the recombination of oxygen to form O2. Specifically, the dissociation of N2O on the active Fe species is facile and leaves an oxidised Fe active site. The surface oxygen must then recombine with another oxygen atom to form O2. It has been demonstrated that the addition of a reductant can facilitate the abstraction of oxygen from the oxidised active site, significantly increasing the observed rate of N2O decomposition at lower temperatures [27, 33,34,35,36,37,38]. Propane [26, 39,40,41,42] has been used as a reductant, in addition to ethane, methane and CO [26, 43,44,45,46,47].

Fe–ZSM-5 can be prepared by various ion-exchange methods, including via wet [48,49,50,51] or solid state [23, 50, 52], or sublimation [28, 32, 53,54,55,56] methodologies. Wet ion exchange includes the use of solvents, while solid state includes solventless mechanical mixing. Sublimation makes use of low evaporation temperature salts, usually FeCl3, as precursors. One challenge with this preparation method is that Cl− ions tend to remain after sublimation and a post-preparation washing step may be required. To combat this we have used a variation of this preparation method: chemical vapour impregnation (CVI). In this method, Fe(acac)3 is used instead of FeCl3, as acetylacetonate precursors are easily removed under vacuum [57,58,59].

During the deposition of Fe on zeolites it is possible to form various types of Fe species such as framework Fe3+ (formed during isomorphous substitution), isolated Fe3+ or Fe2+ anchored to the zeolite framework by either Si–O–Fe or Al–O–Fe bridges, di-nuclear Fe–O–Fe species either in the framework or in the channels, oligomeric Fe oxo-species, and both small nanoparticles and bulk FeOx particles [26, 59,60,61]. Determination of the active Fe species for N2O decomposition remains a challenge; thus far nano-particulate iron [26, 62] and extra-framework Fe have been suggested to catalyse the decomposition of N2O. However, most suggest that extra framework Fe is the active species due to enabling the formation of α-oxygen, [38, 63,64,65,66,67,68] which is formed by decomposing N2O over reversible redox α-Fe sites that switch between Fe2+ and Fe3+ [69, 70].

Treatment of catalysts with acids was reported to increase both their activity and stability, due to the removal of spectator Fe species (FexOy nano-particulates and clusters), with extended periods of time for acid washing not required to remove Fe species, with Fe being removed almost immediately [59]. Due to the stability of the zeolites, acid washing does not greatly affect the pore channels and new mesopores were not created. During mild acid washing only a small quantity of surface Al is removed [71]. This stability implies that only the Fe species present will be affected by the acid washing and the zeolite will remain unchanged [72]. Alternatively literature shows that steaming pre-treatments can be used to extract iron from the pores and into the extra-framework sites [53, 73,74,75,76], however we will not consider this technique in this work.

In this work we have investigated the importance of different Fe species in Fe–ZSM-5 for the decomposition of N2O in the presence and absence of a reductant, propane. In addition to comparing different Fe loadings, we have evaluated the efficacy of acid washing to increase the efficiency of the Fe in the active catalyst and we have used UV/Vis spectroscopy to identify the different Fe species.

2 Experimental

2.1 Catalyst Preparation

A series of Fe–ZSM-5 catalysts (0.4, 1.25, 2.5 wt%) were prepared by CVI following the procedure described by Forde et al. [58]. Prior to catalyst preparation, ZSM-5 (23) and (30) (Zeolyst, 2 g) were dried under vacuum, and then placed into a Schlenk flask and evacuated at room temperature using a vacuum line, followed by heating at 150 °C for 1 h under continuous vacuum to remove any surface water species. ZSM-5 (23 or 30) (Zeolyst, 0.975–0.996 g) and iron acetylacetonate Fe(acac)3 (Sigma Aldrich, 0.0253–0.1582 g) were placed into a glass vial and mixed by manual shaking. The obtained mixture was then transferred to a 50 mL Schlenk flask fitted with a magnetic stirrer bar and sealed. The flask was then evacuated at room temperature using a vacuum line followed by heating at 150 °C for 2 h under continuous vacuum conditions with stirring to induce sublimation and deposition of the organometallic precursor onto the support. The flask was then brought up to atmospheric pressure with air and the sample removed and calcined at 550 °C in static air for 3 h.

Acid washing was performed by heating 10 v/v% HNO3(aq) (50 mL) to 50 °C, adding the catalyst (0.25 g) and stirring for 10 min. The solution was filtered and washed with deionised water (1 L g−1) followed by drying in an oven at 110 °C for 16 h. The samples obtained using this method were denoted as Acid Washed (AW).

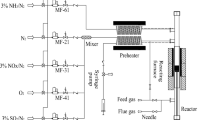

2.2 Catalyst Testing

All reactions were performed at atmospheric pressure in a continuous-flow fixed-bed reactor. A 35 cm length of 1/4 in outer diameter stainless steel tubing was packed with 0.0625 g of catalyst that was sandwiched between two layers of quartz wool. The reaction temperature was tested in the range 200–600 °C. The total flow for all reactions was 100 mL min−1 (GHSV of 45,000 h−1) and the gas feed was 5 v/v% N2O in He or 5 v/v% N2O, 5 v/v% C3H8 in He. All outgoing gaseous products were analysed online using an Agilent 7890B Gas Chromatograph (GC) [columns: Hayesep Q (80–100 mesh, 1.8 m) MolSieve 5A (80–100 mesh, 2 m)] fitted with a thermal conductivity detector.

Here we define Turnover Frequency (TOF) based on the total moles of Fe present by ICP (Eq. 2) as it is a challenge to determine the concentration of surface active sites.

2.3 Catalyst Characterisation

Diffuse reflectance UV/Vis spectra was collected using an Agilent Cary 4000 UV/Vis spectrophotometer. Samples were scanned between 200 and 800 nm (150 nm min−1).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on a Thermo Fisher Scientific K-alpha+ spectrometer. Samples were analysed using a micro-focused monochromatic Al X-ray source (72 W) over an area of approximately 400 microns. Data were recorded at pass energies of 150 eV for survey scans and 40 eV for high resolution scan with 1 eV and 0.1 eV step sizes respectively. Charge neutralisation of the sample was achieved using a combination of both low energy electrons and argon ions. Data analysis was performed in CasaXPS using a Shirley type background and Scofield cross sections, with an energy dependence of -0.6.

Nitrogen adsorption isotherms were collected on a Micrometrics 3Flex. Samples (0.050 g) were degassed (250 °C, 9 h) prior to analysis. Analyses was carried out at − 196 °C with P0 measured continuously. Free space was measured post analysis with He. Pore size analysis was carried out using DFT (N2-Cylindrical Pores-Oxide surface) via the Micrometrics 3Flex software.

Inductively Coupled Plasma – Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) was performed by Exeter Analytical Services using HF digestion to get an accurate Fe loading. The sample was digested by Anton Paar Multiwave 3000 microwave with nitric and HF acids—then the HF was neutralised with the addition of boric acid. A reagent blank was carried out. An internal standard was added to the resulting solutions, and the blank and sample were run against Fe standards by ICP-OES using Thermo Fisher iCAP Duo 7400.

3 Results and Discussion

Although iron-containing zeolites catalyse N2O decomposition, [24,25,26,27, 48,49,50, 72, 78] high reaction temperatures (> 450 °C) are typically required. The effect of varying the Si:Al ratio has been investigated previously [23, 29], the Fe:Al ratio is also an important parameter, as the maximum population of ɑ-Fe sites is directly proportional to the Al content of the zeolite [27, 50, 79]. Additionally, the presence of spectator or extraneous Fe species remains a challenge with respect to calculating real TOF values.

Fe–ZSM-5 Catalysts were prepared with Fe loadings of 0.4 and 1.25 wt% with two different Si:Al ratios. It is clear that the lower Si:Al ratio exhibits higher relative activity (Table 1).The addition of propane enhances the decomposition of N2O by reducing the oxidised α-Fe sites that remain on the surface of the catalysts, preventing turnover of N2O [27, 33,34,35,36,37,38]. Due to the higher activity of the Fe–ZSM-5 (23) parent zeolite catalyst, further investigation was carried out on this Si:Al ratio zeolite [26].

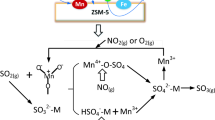

In order to understand the effect of Si:Al ratio, UV/Vis spectroscopy of the various catalysts was performed (Fig. 1). When Fe is added to ZSM-5, four UV-active species can be differentiated. These absorb at: 200–250 nm (isolated Fe3+ in framework sites), 250–350 nm (isolated or oligomeric extra framework Fe species in zeolite channels), 350–450 nm (iron oxide clusters) and > 450 nm (large surface oxide species) [61, 80]. UV/Vis shows how higher Al content leads to high absorbance in the region 250–350 nm due to the presence of more extra-framework ɑ-Fe.

UV/Vis spectra of a series of Fe–ZSM-5 (23 or 30) catalysts and H-ZSM-5 support. Filled triangle framework Fe3+, filled diamond extra framework species, filled circle FexOy clusters, filled square large FexOy species. a H-ZSM-5 (23), b H-ZSM-5 (30), c 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), d 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (30), e 1.25 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), f 1.25 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (30)

An additional Fe–ZSM-5 (23) catalyst was prepared with an Fe weight loading of 2.5% and contrasted to the 0.4 and 1.25 wt% catalysts. Figure 2 (closed symbols) illustrates the conversion of N2O over the four Fe–ZSM-5 (23) catalysts across the temperature range of 400–600 °C. The increasing weight loading of Fe in ZSM-5 increased the conversion of N2O, up to ca. 70% conversion over the 1.25 wt% catalyst, compared to 40% conversion over the 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 catalyst. Increasing the Fe loading to 2.5 wt% did not increase the N2O conversion further (Fig. 2). The 0.4% Fe catalyst exhibited limited activity despite the presence of active extra-framework ɑ-Fe species. Therefore, when N2O decomposition takes place at these sites oxygen recombination is limited due to the oxygen species proximity to combine to form molecular oxygen and, therefore, effectively blocking active sites.

The influence of Fe weight loading on N2O conversion over Fe–ZSM-5 catalysts. Closed symbols: N2O present 5 v/v% N2O in He, open symbols: N2O + Propane present: 5 v/v% N2O, 5 v/v% C3H8 in He, circle 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), square 1.25 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), triangle 2.5 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23). Conditions; total flow rate 100 mL min−1, 0.06 g catalyst, temperature range 200–600 °C, GHSV 45,000 h−1

High loadings of Fe lead to a high proportion of active framework and extra-framework species and due to the increased density of these species, the rate of oxygen recombination is higher, leading to a higher conversion. UV/Vis spectroscopy (Fig. 3) shows that there are a number of distinct Fe species present in the high loaded catalysts, with both FexOy nanoparticle and cluster species present, indicating that not all the Fe is efficiently utilised. Therefore, while a significant proportion of Fe is not necessarily active, there is a high concentration of extra-framework ɑ-Fe sites that can facilitate oxygen recombination and high N2O conversion.

UV/Vis spectra of a series of Fe–ZSM-5 (23) catalysts and H-ZSM-5 support. Filled circle framework Fe3+, filled diamond extra framework species, filled circle FexOy clusters, filled square Large FexOy species. a H-ZSM-5 (23), b H-ZSM-5 (23) AW, c 0.16 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), d 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), e 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23) AW, f 1.25 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), g 2.5 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23)

When propane is added to the reaction feed-stream, the onset of activity shifts from 400 to 450 °C to a much lower temperature (Fig. 2 open symbols). In this context, propane acts as a reductant [26, 39, 40, 42, 81] and limits the formation of site blocking oxygen species on the surface of the catalyst. The rate-limiting step without propane is oxygen recombination. Propane can activate the oxidised α-Fe site forming CO and CO2, which regenerates the active site and allows the reaction to proceed [27, 33,34,35,36]. At lower temperatures (< 500 °C) minor quantities of propene, ethene and ethane are produced, however, at higher temperatures the selectivity shifts to exclusively CO and CO2.

Comparing the reaction data (Fig. 2) to the UV/Vis spectroscopy (Fig. 3), it is possible to observe that the more active catalysts have a higher proportion of framework and extra framework ɑ-Fe species. This is the case in the 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 catalyst, where UV/Vis spectroscopy (Fig. 3) shows that framework and extra-framework species are present, with only a small absorbance due to FexOy nano-particles and clusters. By contrast, the poor activity of 1.25 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 correlates with the high proportion of nanoparticles and clusters of FexOy present, which limit the number of Fe ions available to form the active species.

Peneau et al. demonstrated that using dilute HNO3, it is possible to remove excess iron and spectator species from the catalyst, which was investigated for the selective oxidation of ethane by H2O2 [59]. Here, 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23) was identified as a suitable catalyst formulation for acid washing, due to the presence of extra-framework ɑ-Fe species and minor levels of spectator FexOy nano-particulates and clusters. Previous work within the group has shown that it is difficult to distinguish between the Fe species present at higher weight loadings, therefore lower weight loadings were selected for acid washing to enable changes to be noted [82, 83]. After acid washing the calcined catalyst, ICP-OES analysis of the digested samples revealed that the weight loading had reduced to 0.16%. Figure 4a illustrates the activity of the as-prepared parent catalyst, the acid washed 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 catalyst, a 0.16 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (prepared by CVI for comparison to the AW catalyst) as well as the analogous H-ZSM-5 catalysts, which were tested to confirm that the support alone was not active for the reaction. The 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23) sample has an N2O conversion of 40% at 600 °C, however, over the acid washed catalyst the conversion was lower at 600 °C at 25%.

a Influence of Fe loading and acid washing over Fe–ZSM-5 catalysts for N2O conversion (closed symbols); Left pointed triangle 0.16 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), circle 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), right pointed triangle 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23) acid washed, diamond H-ZSM-5 (23), inverted triangle H-ZSM-5 (23) acid washed. Conditions: 5 v/v% N2O in He, total flow rate 100 mL min−1, 0.06 g catalyst, temperature range 400–600 °C, GHSV 45,000 h−1. b N2O conversion with propane present; open symbols. Conditions: 5 v/v% N2O, 5 v/v% C3H8 in He total flow rate 100 mL min−1, 0.06 g catalyst, temperature range 400–600 °C, GHSV 45,000 h−1

UV/Vis Spectroscopy (Fig. 3) supports the hypothesis that the decrease in activity observed after acid washing was due to the removal of framework Fe3+ ions which are extracted and deposited onto the surface of the catalyst as nanoparticles of FexOy (270 nm). UV/Vis Spectroscopy of 0.16 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 suggests that the Fe is present as framework Fe3+ and extra-framework ɑ-Fe species only (Fig. 3). The lower activity of this catalyst further suggests that the proximity of the Fe sites to each other is crucial to achieve high activity in N2O decomposition. When propane is present (Fig. 4b) however, the relative proximity of active sites does not affect activity as propane can abstract oxygen from a single oxidised Fe site.

UV/Vis Spectroscopy was further used to understand the contrasting influence of the Fe loading concentration on N2O decomposition with and without propane. The spectrum of H-ZSM-5 (23) shows that framework Fe3+ species are present in the parent zeolite due to the absorbance at 220 nm (Fig. 3) and are likely to be impurities introduced during manufacture [84]. However, acid washing the H-ZSM-5 has the effect of re-dispersing the Fe species and forming Fe with extra-framework character. The 0.16 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 catalyst appears to possess both framework (< 250 nm) and extra-framework Fe (280 nm) only. Both the 1.25 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 and 2.5 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 catalysts contains all species present, with framework (< 250 nm), extra-framework Fe (280 nm), iron oxide nanoparticles (400 nm) and large clusters of iron oxide (> 450 nm). The spectrum of 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23) shows that there are three species of Fe present, framework Fe3+, extra-framework ɑ-Fe and large FexOy clusters. In contrast, the spectrum of 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23) acid washed sample shows that there are all four species of Fe present. Most notably, a reduced absorbance due to extra- framework ɑ-Fe being extracted and an increased absorbance from deposited FexOy nanoparticles and clusters.

Further characterisation was performed on the 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 and acid washed samples with XPS (Table 2). XPS measurements revealed a significant loss of Fe from the surface of the catalyst following acid washing, as the atomic % of Fe dropped from 2.02 to 0.28%, in addition to a decrease in the intensity of the Fe peak (Fig. 5). Consideration of the surface and bulk Fe content, as determined using XPS and ICP-OES showed a drop in the surface:bulk Fe ratio after acid washing (5.05 and 1.75 for the as-prepared and acid washed 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 catalysts, respectively). This confirmed that Fe was preferentially removed from the surface of the catalyst rather than within the micro-porous channels. Furthermore, XPS showed that the binding energy of Fe is 711 eV in the calcined and acid washed catalysts, this alongside the satellite at 719 eV indicates that there is Fe3+ species present [85, 86]. After the addition of iron to the ZSM-5 the binding energy of both the Al and Si shift to slightly higher binding energies. Shifts in the Al spectrum from 102.9 eV in ZSM-5 to 103.4 eV in the calcined and acid washed catalyst, with Si shifting from 74.1 to 74.9 eV were observed in both catalysts. This shift to a higher binding energy indicates that Fe has substituted into the lattice, [87,88,89] and corresponds with the UV/Vis spectroscopy as there is a larger absorption in the framework Fe3+ region indicating that Fe has substituted into the framework.

Surface area measurements for all catalysts remained constant at around 430 m2 g−1. This is consistent with the parent zeolite, which has a surface area of 423 m2 g−1. The micropore volume of H-ZSM-5 (23) is 0.167 cm3 g−1, this varies by ± 0.003 cm3 g−1 when iron is added and calcined and then acid washed, (Table 2). The consistency of surface area and micropore volume during the catalyst preparation, calcination, and acid washing indicates that H-ZSM-5 (23) is stable under the pre-treatment conditions.

Due to the complexity in resolving the active Fe species, the TOF over the catalysts samples was calculated for N2O decomposition (Fig. 6a) using the total moles of Fe present in the sample. The low loaded Fe–ZSM-5 sample with 0.16 wt% Fe achieved a TOF of ca. 3.99 × 103 s−1 at 600 °C. The TOF of the acid washed H-ZSM-5 catalyst at 600 °C is an order of magnitude greater than the Fe based catalyst, when propane is present at 600 °C (Fig. 6b). This is due to the zeolite achieving 52% conversion (Fig. 6b) and only having trace amounts of iron present (245 ppm) typically in framework positions. This results in an extremely high TOF based on the ppm of iron present, however in reality a very low yield of nitrogen was observed. The activity of the H-ZSM-5 after acid washing is due to the formation of active extra-framework ɑ-Fe from Fe that has been removed from the framework [63, 64, 90]. The TOF of the acid washed catalyst was calculated to be 0.94 × 103 s−1, which compares to 0.69 × 103 s−1 achieved over the parent catalyst at 600 °C (Fig. 6a). When comparing the activity of the parent and acid washed catalyst in the presence of propane, the difference in activity is less significant and at higher temperatures (> 550 °C) the activity is comparable: both catalysts achieved 95% N2O conversion at 600 °C (Fig. 4b). In terms of TOF, the activity of the acid washed Fe–ZSM-5 catalyst was two and a half times that of the calcined equivalent catalyst (Fig. 6b). However, the TOF over the 0.16 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 catalyst is ca. 8.5 × 103 s−1 at > 550 °C, with propane present. Park et al. reported a TOF of 1.8 × 103 s−1 for N2O decomposition at 550 °C using 1.96 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (27) [50] compared to 2.59 × 103 s−1 achieved by 0.16% Fe–ZSM-5 (23) at 550 °C under similar conditions, demonstrating the superior activity of the catalyst prepared herein.

a TOF of N2O decomposition over a series of Fe–ZSM-5 catalysts that have been calcined or acid washed, closed symbols. Left pointed triangle 0.16 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), circle 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), square 1.25 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23), triangle 2.5 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23) right pointed triangle 0.4 wt% Fe–ZSM-5 (23) AW. Conditions: 5 v/v% N2O in He, total flow rate 100 mL min−1, 0.06 g catalyst, temperature range 400–600 °C, GHSV 45,000 h−1. b TOF of N2O decomposition with propane present, open symbols; Conditions: 5 v/v% N2O, 5 v/v% C3H8 in He, total flow rate 100 mL min−1, 0.06 g catalyst, temperature range 400–600 °C, GHSV 45,000 h−1

4 Conclusions

At low Fe loadings, Fe–ZSM-5 (23) catalysts prepared by CVI have two species of Fe present, Framework Fe3+ and isolated extra-framework FexOy in the pores, as shown by UV/Vis spectroscopy. However, when high-loading Fe–ZSM-5 is prepared by this method there are two additional species of Fe present: FexOy nanoparticles and large clusters. The species of iron present in low loaded catalysts, framework and extra-framework Fe, are the active species for N2O decomposition, which lead to high conversion when propane is present, however without propane the activity of these catalysts is limited by slow oxygen desorption, due to the low proximity of active Fe sites. Therefore, the oxygen desorption step becomes rate limiting. At higher weight loadings with only N2O present the activity of the catalyst is increased as the density of the active sites increase, therefore, increasing the rate of oxygen desorption. When acid washing is performed it is not possible to selectively remove the FexOy nanoparticles and clusters, but instead extra-framework Fe is extracted from the pores and deposited on the surface, leading to a decrease in conversion, but increase in TOF.

References

Pérez-Ramírez J, Kapteijn F, Schöffel K, Moulijn JA (2003) Formation and control of N2O in nitric acid production: where do we stand today? Appl Catal B 44:117–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0926-3373(03)00026-2

Weimann J (2003) Toxicity of nitrous oxide. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 17:47–61

Grace P, Barton L (2014) http://theconversation.com/meet-n2o-the-greenhouse-gas-300-times-worse-than-co2-35204. In: http://theconversation.com/meet-n2o-the-greenhouse-gas-300-times-worse-than-co2-35204. Accessed 12 June 2017

IPCC (2007) Climate change 2007: synthesis report. In: The Core Writing Team, Pachauri RK, Reisinger A (eds), Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. IPCC, Geneva, p 104

Li L, Xu J, Hu J, Han J (2014) Reducing nitrous oxide emissions to mitigate climate change and protect the ozone layer. Environ Sci Technol 48:5290–5297. https://doi.org/10.1021/es404728s

IPCC (2013) Climate Change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

UNEP (2013) Drawing down nitrous oxide to protect climate and the ozone layer. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi

Maroufi SS, Gharavi MJ, Behnam M, Samadikuchaksaraei A (2011) Nitrous oxide levels in operating and recovery rooms of Iranian hospitals. Iran J Public Health 40:75–79

Space Propulsion Group (2012) http://www.spg-corp.com/nitrous-oxide-safety.html. In: http://www.spg-corp.com/nitrous-oxide-safety.html

Kapteijn F, Rodriguez-Mirasol J, Moulijn JA (1996) Heterogeneous catalytic decomposition of nitrous oxide. Appl Catal B 9:25–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/0926-3373(96)90072-7

Kumar S, Teraoka Y, Joshi AG et al (2011) Ag promoted La0.8Ba0.2MnO3 type perovskite catalyst for N2O decomposition in the presence of O2, NO and H2O. J Mol Catal A 348:42–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2011.07.017

Kumar S, Vinu A, Subrt J et al (2012) Catalytic N2O decomposition on Pr0.8Ba0.2MnO3 type perovskite catalyst for industrial emission control. Catal Today 198:125–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2012.06.015

Dacquin JP, Lancelot C, Dujardin C et al (2009) Influence of preparation methods of LaCoO3 on the catalytic performances in the decomposition of N2O. Appl Catal B 91:596–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2009.06.032

Kartha KK, Pai MR, Banerjee AM et al (2011) Modified surface and bulk properties of Fe-substituted lanthanum titanates enhances catalytic activity for CO + N2O reaction. J Mol Catal A 335:158–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2010.11.028

Russo N, Mescia D, Fino D et al (2007) N2O decomposition over perovskite catalysts. Ind Eng Chem Res 46:4226–4231. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie0612008

Zabilskiy M, Erjavec B, Djinović P, Pintar A (2014) Ordered mesoporous CuO-CeO2 mixed oxides as an effective catalyst for N2O decomposition. Chem Eng J 254:153–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2014.05.127

Zhou H, Hu P, Huang Z et al (2013) Preparation of NiCe mixed oxides for catalytic decomposition of N2O. Ind Eng Chem Res 52:4504–4509. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie400242p

Zhou H, Huang Z, Sun C et al (2012) Catalytic decomposition of N2O over CuxCe1-xOy mixed oxides. Appl Catal B Environ 125:492–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.06.021

Abu-Zied BM, Soliman SA, Abdellah SE (2015) Enhanced direct N2O decomposition over CuxCo1-xCo2O4(0.0 ≤ x ≤ 1.0) spinel-oxide catalysts. J Ind Eng Chem 21:814–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiec.2014.04.017

Stelmachowski P, Maniak G, Kaczmarczyk J et al (2014) Mg and Al substituted cobalt spinels as catalysts for low temperature deN2O-evidence for octahedral cobalt active sites. Appl Catal B 146:105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.05.027

Amrousse R, Tsutsumi A, Bachar A, Lahcene D (2013) N2O catalytic decomposition over nano-sized particles of Co-substituted Fe3O4 substrates. Appl Catal A 450:253–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2012.10.036

Konsolakis MI (2015) Recent advances on nitrous oxide (N2O) decomposition over non–noble metal oxide catalysts: catalytic performance, mechanistic considerations and surface chemistry aspects. ACS Catal. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.5b01605

Rauscher M, Kesore K, Mönnig R et al (1999) Preparation of a highly active Fe-ZSM-5 catalyst through solid-state ion exchange for the catalytic decomposition of N2O. Appl Catal A 184:249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0926-860X(99)00088-5

Abu-Zied BM, Schwieger W, Unger A (2008) Nitrous oxide decomposition over transition metal exchanged ZSM-5 zeolites prepared by the solid-state ion-exchange method. Appl Catal B 84:277–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2008.04.004

Sklenak S, Andrikopoulos PC, Boekfa B et al (2010) N2O decomposition over Fe-zeolites: structure of the active sites and the origin of the distinct reactivity of Fe-ferrierite, Fe-ZSM-5, and Fe-beta. A combined periodic DFT and multispectral study. J Catal 272:262–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2010.04.008

Abdulhamid H, Fridell E, Skoglundh M (2004) Influence of the type of reducing agent (H2, CO, C3H6 and C3H8) on the reduction of stored NOX in a Pt/BaO/Al2O3 model catalyst. Top Catal 30/31:161–168. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:TOCA.0000029745.87107.b8

Reimer RWoodB, Bell J AT (2002) Studies of N2O adsorption and decomposition on Fe–ZSM-5. J Catal 209:151–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcat.2002.3610

Sobalik Z, Novakova J, Dedecek J et al (2011) Tailoring of Fe-ferrierite for N2O decomposition: on the decisive role of framework Al distribution for catalytic activity of Fe species in Fe-ferrierite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 146:172–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.05.004

Melián-Cabrera I, van Eck ERH, Espinosa S et al (2017) Tail gas catalyzed N2O decomposition over Fe-beta zeolite. On the promoting role of framework connected AlO6 sites in the vicinity of Fe by controlled dealumination during exchange. Appl Catal B 203:218–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.10.019

Mauvezin M, Delahay G, Coq B et al (2001) Identification of iron species in Fe-BEA: influence of the exchange level. J Phys Chem B 105:928–935. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0021906

Øygarden AH, Pérez-Ramírez J (2006) Activity of commercial zeolites with iron impurities in direct N2O decomposition. Appl Catal B 65:163–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2006.03.002

Jíša K, Nováková J, Schwarze M et al (2009) Role of the Fe-zeolite structure and iron state in the N2O decomposition: comparison of Fe-FER, Fe-BEA, and Fe-MFI catalysts. J Catal 262:27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2008.11.025

Guesmi H, Berthomieu D, Kiwi-Minsker L (2008) Nitrous oxide decomposition on the binuclear [Fe II (µ-O)(µ-OH)Fe II] center in Fe-ZSM-5 zeolite. J Phys Chem C 112:20319–20328. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp808044r

Sang C, Kim BH, Lund CRF (2005) Effect of NO upon N2O decomposition over Fe/ZSM-5 with low iron loading. J Phys Chem B 109:2295–2301. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp048884m

Hansen N, Heyden A, Bell AT, Keil FJ (2007) A reaction mechanism for the nitrous oxide decomposition on binuclear oxygen bridged iron sites in {Fe-ZSM-5}. J Phys Chem C 111:2092–2101. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp065574q

Bulushev DA, Kiwi-minsker L, Renken A (2004) Dynamics of N2O decomposition over Fe/ZSM-5 catalysts: effects of. 211:2004

Sun K, Xia H, Hensen E et al (2006) Chemistry of N2O decomposition on active sites with different nature: effect of high temperature treatment of Fe/ZSM-5. J Catal 238:186–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2005.12.013

Pirngruber GD (2003) The surface chemistry of N2O decomposition on iron containing zeolites (I). J Catal 219:456–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9517(03)00220-3

Ohtsuka H, Tabata T, Okada O et al (1997) A study on selective reduction of NOx by propane on Co-Beta. Catal Lett 44:265–270

Ohtsuka H, Tabata T, Okada O et al (1998) A study on the roles of cobalt species in NOx reduction by propane on Co-Beta. Catal Today 42:45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(98)00075-3

Van Den Brink RW, Booneveld S, Verhaak MJFM, De Bruijn FA (2002) Selective catalytic reduction of N2O and NOx in a single reactor in the nitric acid industry. Catal Today 75:227–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(02)00073-1

Centi G, Vazzana F (1999) Selective catalytic reduction of N2O in industrial emissions containing O2, H2O and SO2: behavior of Fe/ZSM-5 Catalysts. Catal Today 53:683–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(99)00155-8

Djéga-Mariadassou G, Fajardie F, Tempère JF et al (2000) A general model for both three-way and deNO(x) catalysis: dissociative or associative nitric oxide adsorption, and its assisted decomposition in the presence of a reductant. Part I. Nitric oxide decomposition assisted by CO over reduced or oxidized rhodiu. J Mol Catal A 161:179–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1381-1169(00)00334-4

He L, Wang LC, Sun H et al (2009) Efficient and selective room-temperature gold-catalyzed reduction of nitro compounds with CO and H2O as the hydrogen source. Angew Chem Int Ed 48:9538–9541. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200904647

Teramura K, Tanaka T, Ishikawa H et al (2004) Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO in the presence of H2 or CH4 as a reductant over MgO. J Phys Chem B 108:346–354. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0362943

Yogo K, Ihara M, Terasaki I, Kikuchi E (1993) Selective reduction of nitrogen monoxide with methane or ethane on gallium ion-exchanged ZSM-5 in oxygen-rich atmosphere. Chem Lett 22:229–232. https://doi.org/10.1246/cl.1993.229

Burch R, Loader PK (1994) Investigation of Pt/Al2O3, and Pd/Al2O3 & catalysts for the combustion of methane at low concentrations. Appl Catal B 5:149–164

Pieterse JAZ, Booneveld S, Van Den Brink RW (2004) Evaluation of Fe-zeolite catalysts prepared by different methods for the decomposition of N2O. Appl Catal B 51:215–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2004.02.013

Li L, Shen Q, Li J et al (2008) Iron-exchanged FAU zeolites: preparation, characterization and catalytic properties for N2O decomposition. Appl Catal A 344:131–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2008.04.011

Park JH, Choung JH, Nam IS, Ham SW (2008) N2O decomposition over wet- and solid-exchanged Fe-ZSM-5 catalysts. Appl Catal B 78:342–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.09.020

Chen B, Liu N, Liu X et al (2011) Study on the direct decomposition of nitrous oxide over Fe-beta zeolites: from experiment to theory. Catal Today 175:245–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2011.04.010

Christoforou SC, Efthimiadis EA, Vasalos IA (2002) Catalytic conversion of N2O to N2 over metal-based catalysts in the presence of hydrocarbons and oxygen. Catal Lett 79:137–147

Zhu Q, Hensen EJ, Mojet BL et al (2002) N2O decomposition over Fe/ZSM-5: reversible generation of highly active cationic Fe species. Chem Commun. https://doi.org/10.1039/B202843C

Kucherov a V, Montreuil CN, Kucherova TN, Shelef M (1998) In situ high-temperature ESR characterization of FeZSM-5 and FeSAPO-34 catalysts in flowing mixtures of NO, C3H6, and O-2. Catal Lett 56:173–181

Lee H-T, Rhee H-K (1999) Stability of Fe/ZSM-5 De-NOx catalyst: effects of iron loading and remaining Brønsted acid sites. Catal Lett 61:71–76. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019044032219

Lobree LJ, Hwang I, Reimer J, Bell AT (1999) An in situ infrared study of NO reduction by C3H8 over Fe-ZSM-5. Catal Lett 63:233–240

Forde MM, Armstrong RD, Hammond C et al (2013) Partial oxidation of ethane to oxygenates using Fe- and Cu-containing ZSM-5. J Am Chem Soc 135:11087–11099. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja403060n

Forde MM, Armstrong RD, McVicker R et al (2014) Light alkane oxidation using catalysts prepared by chemical vapour impregnation: tuning alcohol selectivity through catalyst pre-treatment. Chem Sci. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4sc00545g

Peneau V, Armstrong RD, Shaw G et al (2017) The low-temperature oxidation of propane by using H2O2 and Fe/ZSM-5 catalysts: insights into the active site and enhancement of catalytic turnover frequencies. ChemCatChem 9:642–650. https://doi.org/10.1002/cctc.201601241

Ates A, Hardacre C, Goguet A (2012) Oxidative dehydrogenation of propane with N2O over Fe-ZSM-5 and Fe–SiO2: influence of the iron species and acid sites. Appl Catal A 441–442:30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2012.06.038

Pérez-Ramírez J, Groen JC, Brückner A et al (2005) Evolution of isomorphously substituted iron zeolites during activation: comparison of Fe-beta and Fe-ZSM-5. J Catal 232:318–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2005.03.018

Kapteijn F, Mul G, Moulijn J, Pérez-Ramírez J (2002) Highly active SO2-resistant ex -framework FeMFI catalysts for direct N2O decomposition. Appl Catal B 35:227–234

Sun K, Zhang H, Xia H et al (2004) Enhancement of α-oxygen formation and N2O decomposition on Fe/ZSM-5 catalysts by extraframework Al. Chem Commun. https://doi.org/10.1039/B408854A

Hensen EJM, Zhu Q, Hendrix MMRM et al (2004) Effect of high-temperature treatment on Fe/ZSM-5 prepared by chemical vapor deposition of FeCl3: I. Physicochemical characterization. J Catal 221:569–583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2003.09.024

Pérez-Ramírez J (2003) Active site structure sensitivity in N2O conversion over FeMFI zeolites. J Catal 218:234–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9517(03)00087-3

Sobolev V (1993) Catalytic properties of ZSM-5 zeolites in N2O decomposition: the role of iron. J Catal 139:435–443

Panov GI, Kharitonov AS, Sobolev VI (1993) Oxidative hydroxylation using dinitrogen monoxide: a possible route for organic synthesis over zeolites. Appl Catal A 98:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/0926-860X(93)85021-G

Panov GI, Sobolev VI, Kharitonov AS (1990) The role of iron in N2O decomposition on ZSM-5 zeolite and reactivity of the surface oxygen formed. J Mol Catal 61:85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-5102(90)85197-P

Panov GI, Starokon EV, Pirutko LV et al (2008) New reaction of anion radicals O-with water on the surface of FeZSM-5. J Catal 254:110–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2007.12.001

Parfenov MV, Starokon EV, Pirutko LV, Panov GI (2014) Quasicatalytic and catalytic oxidation of methane to methanol by nitrous oxide over FeZSM-5 zeolite. J Catal 318:14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2014.07.009

Fernandez C, Stan I, Gilson JP et al (2010) Hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolites in shape-selective xylene isomerization: role of mesoporosity and acid site speciation. Chemistry 16:6224–6233. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.200903426

Wu M, Wang H, Zhong L et al (2016) Effects of acid pretreatment on Fe-ZSM-5 and Fe-beta catalysts for N2O decomposition. Cuihua Xuebao/Chinese J Catal 37:898–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1872-2067(15)61052-X

Sun K, Zhang H, Xia H et al (2004) Enhancement of α-oxygen formation and N2O decomposition on Fe/ZSM-5 catalysts by extraframework Al. Chem Commun 216:2480–2481. https://doi.org/10.1039/B408854A

Dubkov KA, Ovanesyan NS, Shteinman AA et al (2002) Evolution of iron states and formation of α-sites upon activation of FeZSM-5 zeolites. J Catal 207:341–352. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcat.2002.3552

Ribera A, Arends IWCE, De Vries S et al (2000) Preparation, characterization, and performance of FeZSM-5 for the selective oxidation of benzene to phenol with N2O. J Catal 195:287–297. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcat.2000.2994

Panov GI, Uriarte AK, Rodkin MA, Sobolev VI (1998) Generation of active oxygen species on solid surfaces. Opportunity for novel oxidation technologies over zeolites. Catal Today 41:365–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-5861(98)00026-1

Forde MM, Kesavan L, Bin Saiman MI et al (2014) High activity redox catalysts synthesized by chemical vapor impregnation. ACS Nano 8:957–969. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn405757q

Li G, Pidko EA, Filot IAW et al (2013) Catalytic properties of extraframework iron-containing species in ZSM-5 for N2O decomposition. J Catal 308:386–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2013.08.010

Wood BR, Reimer JA, Bell AT et al (2004) Nitrous oxide decomposition and surface oxygen formation on Fe-ZSM-5. J Catal 224:148–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcat.2004.02.025

Kumar MS, Perez-Ramirez J, Debbagh MN et al (2006) Evidence of the vital role of the pore network on various catalytic conversions of N2O over Fe-silicalite and Fe-SBA-15 with the same iron constitution. Appl Catal B 62:244–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.07.012

Van Den Brink RW, Booneveld S, Verhaak MJFM, De Bruijn FA (2002) Selective catalytic reduction of N2O and NOx in a single reactor in the nitric acid industry. Catal Today. 75(1–4):227–232

Chow YK, Dummer NF, Carter JH et al (2018) A kinetic study of methane partial oxidation over Fe-ZSM-5 using N2O as an oxidant. ChemPhysChem 19:402–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphc.201701202

Xu J, Armstrong RD, Shaw G et al (2016) Continuous selective oxidation of methane to methanol over Cu- and Fe-modified ZSM-5 catalysts in a flow reactor. Catal Today 270:93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2015.09.011

Hammond C, Forde MM, Ab Rahim MH et al (2012) Direct catalytic conversion of methane to methanol in an aqueous medium by using copper-promoted Fe-ZSM-5. Angew Chem Int Ed 51:5129–5133. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201108706

Biesinger MC, Payne BP, Grosvenor AP et al (2011) Resolving surface chemical states in XPS analysis of first row transition metals, oxides and hydroxides: Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni. Appl Surf Sci 257:2717–2730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.10.051

Graat PCJ, Somers MAJ (1996) Simultaneous determination of composition and thickness of thin iron-oxide films from XPS Fe 2p spectra. Appl Surf Sci 100–101:36–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-4332(96)00252-8

Södergren S, Siegbahn H, Rensmo H et al (1997) Lithium intercalation in nanoporous anatase TiO2 studied with XPS. J Phys Chem B 101:3087–3090. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp9639399

Chen W, Xu Q, Hu YS et al (2002) Effect of modification by poly(ethylene oxide) on the reversibility of insertion/extraction of Li+ ion in V2O5 xerogel films. J Mater Chem 12:1926–1929. https://doi.org/10.1039/b203056j

Stakheev AY, Shpiro ES, Apijok J (1993) XPS and XAES study of titania-silica mixed oxide system. J Phys Chem 97:5668–5672. https://doi.org/10.1021/j100123a034

Pérez-Ramírez J, Kapteijn F, Brückner A (2003) Active site structure sensitivity in N2O conversion over FeMFI zeolites. J Catal 218:234–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9517(03)00087-3

Acknowledgements

ERC Funding ‘After the GoldRush’ code, ERC-AtG-291319. Cardiff Catalysis Institute would like to thank Exeter Analytical for the ICP-OES data. The authors would like to thank Dr. Robert Armstrong for fruitful discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Richards, N., Nowicka, E., Carter, J.H. et al. Investigating the Influence of Fe Speciation on N2O Decomposition Over Fe–ZSM-5 Catalysts. Top Catal 61, 1983–1992 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-018-1024-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-018-1024-0