Abstract

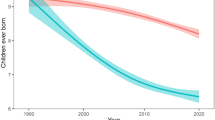

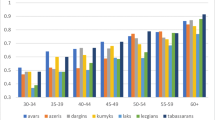

Compared with that in other countries, the issue of fertility in China is more complicated because of its restriction policy or system. Several major hypotheses have been proposed to explain and predict the impact of migration on China’s fertility regardless of China’s real situation. Therefore, this paper analyzes the impact of migration on fertility considering China’s underlying restrictions using the data from the Chinese General Social Survey carried out in 2008. The social class in this study was divided into two, namely urban class and rural class. By building the 2 × 2 mobility tables and the diagonal mobility model, the study determined the impact of migration on fertility and analyzed the influence of some restrictions, such as family planning, traditional fertility concept, and household registration system. Results show that migration greatly affects fertility: upward migration (i.e., from rural to urban) may decrease the fertility, whereas downward migration (i.e., from urban to rural) may increase it. The degree of decline on fertility is greater than that of increase. Family planning still plays a role in fertility decline. Traditional concepts on fertility, for example, bringing up sons to take care of parents in their old age and preferring boys to girls, are anchored on the people’s mind, which is detrimental to the stability of the fertility rate. Moreover, the household registration system primarily influences the fertility behavior of temporary migration, with a negative relationship between them.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Afridi, F., Li, S. X., & Ren, Y. (2012). Social identity and inequality: The impact of China’s Hukou system. IZA Discussion Paper No. 6417. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2028297.

Andersson, G. (2004). Childbearing after migration: Fertility patterns of foreign-born women in Sweden. International Migration Review, 38(2), 747–774.

Bao, S. M., Bodvarsson, O. B., Hou, J. W., & Zhao, Y. H. (2011). The regulation of migration in a transition economy: China’s Hukou system. Contemporary Economic Policy, 29(4), 564–579.

Blau, A., & Duncan, C. (1967). The American occupational structure. New York: The Free Press.

Bongaarts, J., & Sinding, S. W. (2009). A response to critics of family planning programs. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(1), 39–44.

Cai, Y. (2008). Assessing fertility levels in China using variable-r method. Demography, 45(2), 371–381.

Cai, Y. (2010). China’s below-replacement fertility: Government policy or socioeconomic development? Population and Development Review, 36(3), 419–440.

Chan, K. M. (2010). The household registration system and migrant labor in China: Notes on a debate. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 357–364.

Chen, W., & Wu, L. L. (2006). China’s low fertility and its determinants. Population Research, 30(1), 13–20.

Clifford, D. (2009). Spousal separation, selectivity and contextual effects: Exploring the relationship between international labor migration and fertility in post-Soviet Tajikistan. Demographic Research, 21(32), 946–972.

Dreze, J., & Murthi, M. (2001). Fertility, education, and development: Evidence from India. Population and Development Review, 27(1), 33–63.

Dribe, M., Bavel, J. V., & Campbell, C. (2012). Social mobility and demographic behavior: Long term perspectives. Demographic Research, 26(8), 173–190.

Ebenstein, A. (2010). The “missing girls” of China and the unintended consequences of the one child policy. Journal of Human Resources, 45(1), 87–115.

Erikson, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (2009). Social class, family background, and intergenerational mobility: A comment on Mcintosh and Munk. European Economic Review, 53, 118–120.

Frejka, T., & Ross, J. (2001). Paths to subreplacement fertility: The empirical evidence. Population and Development Review, 27, 213–254.

Goldberg, D. (1959). The fertility of two-generation urbanites. Population Studies, 12(3), 214–222.

Goldberg, D. (1960). Another look at the Indianapolis fertility data. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly, 38(1), 23–36.

Goldstein, A., White, M., & Goldstein, S. (1997). Migration, fertility, and state policy in Hubei Province, China. Demography, 34(4), 481–491.

Goodkind, D. (2011). Child under reporting, fertility and sex ratios imbalance in China. Demography, 48(1), 291–316.

Greenhalgh, S. (2008). Just one child: Science and policy in Deng’s China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Greenhalgh, S., & Winckler, A. E. (2005). Governing China’s population: From Leninist to neoliberal biopolitics. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gu, B., Wang, F., Guo, Z., & Zhang, E. (2007). China’s local and national fertility policies at the end of the twentieth century. Population and Development Review, 33(1), 129–148.

Hertel, T., & Zhai, F. (2006). Labor market distortions, rural-urban inequality and the opening of China’s economy. Economic Modelling, 23, 76–109.

Hua, Y. F. (2009). The development and prospects of China’s old age security system. Social Sciences in China, 30(1), 185–196.

Koc, I., & Onan, I. (2004). International Migrants’ remittances and welfare status of the left-behind families in Turkey. International Migration Review, 38(1), 78–112.

Kulu, H. (2005). Migration and fertility: Competing hypotheses re-examined. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie, 21(1), 51–87.

Li, Y., Niu, S. W., Ma, L. B., & Luo, G. H. (2011). Chinese population, growth, and the environment: A new analysis. Remote Sensing, Environment and Transportation Engineering, 28, 5802–5805.

Li, H. B., & Zhang, J. S. (2007). Do high birth rates hamper economic growth? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(1), 110–117.

Lindstrom, D. P., & Giorguli, S. (2002). Short and long-term effects of US migration experience on Mexican women’s fertility. Social Forces, 80(4), 1341–1368.

Lindstrom, D. P., & Giorguli, S. (2007). The interrelationship of fertility, family maintenance, and Mexico-U.S. migration. Demographic Research, 17(28), 821–858.

Long, H., Zou, J., & Liu, Y. (2009). Differentiation of rural development driven by industrialization and urbanization in eastern coastal China. Habitat International, 33(4), 454–462.

Ma, Y. T. (2007). The demographic dividend grow with each passing day is dynamic 21CN great-leap-forward development. China’s Population Science, 1, 2–9.

Mason, K. O. (1992). Culture and the fertility transition: Thoughts on theories of fertility decline. Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”, 48(3–4), 1–14.

Mcnicoll, G. (2001). Government and fertility in transitional and post-transitional societies. Population and Development Review, 27, 129–159.

Milewski, N. (2010). Immigrant fertility in West Germany: Is there a socialization effect in transitions to second and third births? European Journal of Population, 26, 297–323.

Morgan, S. P., Guo, Z. G., & Hayford, R. S. (2009). China’s below-replacement fertility: Recent trends and future prospects. Population and Development Review, 35(3), 605–629.

Orrenius, P., Zavodny, M., & Kerr, M. (2012). Chinese immigrants in the US labor market: Effect of post-Tiananmen immigration policy. International Migration Review, 2, 456–482.

Peng, Y. (2010). When formal laws and informal norms collide: Lineage networks versus birth control policy in China. The American Journal of Sociology, 116(3), 770–805.

Peng, T. (2011a). The impact of citizenship on labour process: State, capital and labour control in South China. Work, Employment & Society, 25(4), 726–741.

Peng, X. (2011b). China’s demographic history and future challenges. Science, 333(6042), 581–587.

Presser, H., Hattori, M., Parashar, S., Raley, S., & Sa, Z. (2006). Demographic change and response: Social context and the practice of birth control in six countries. Journal of Population Research, 23(2), 135–163.

Quaranta, L. (2011). Agency of change: Fertility and seasonal migration in a nineteenth century alpine community. European Journal of Population, 27, 457–485.

Retherford, R. D., Choe, M. K., Chen, J., Li, X., & Cui, H. (2005). How far has fertility in China really declined? Population and Development Review, 31(1), 57–84.

Rosenzweig, M. R., & Zhang, J. (2009). Do population control policies induce more human capital investment? Twins, birth weight and China’s “one-child” policy. Review of Economic Studies, 76(3), 1149–1174.

Scharping, T. (2003). Birth control in China, 1949–2000: Population policy and demographic development. London: Routledge.

Sobel, M. J. (1981). Myopic solutions of markov decision processes and stochastic games. Operations Research, 29(5), 995–1009.

Whalley, J., & Zhang, S. (2007). A numerical simulation analysis of (Hukou) labor mobility restrictions in China. Journal of Development Economics, 83, 392–410.

Wu, X. G., & Treiman, D. J. (2004). The household registration system and social stratification in China, 1955–1996. Demography, 41(2), 363–384.

Yang, X. (2000). The fertility impact of temporary migration in China: A detachment hypothesis. European Journal of Population, 16, 163–183.

Yang, Y. M., & Peng, J. (2003). Present status, problems, and countermeasures for family planning work of floating population—a case study of Chongqing. Population and Family Planning, 9, 22–24.

Yao, S., Zhang, Z., & Hanmer, L. (2004). Growing inequality and poverty in China. China Economic Review, 15, 145–163.

Ye, H., & Wu, X. G. (2011). Fertility decline and trend in educational gender inequality in China. Study of Sociology, 5, 153–178.

You, H. X., & Poston, D. L. (2004). Are floating migrants in China child-bearing guerrillas: An analysis of floating migration and fertility. Asia and Pacific Migration Journal, 13(4), 405–422.

Zhao, Z., & Guo, Z. (2010). China’s below replacement fertility: A further exploration. Canadian Studies in Population, 37(3–4), 525–562.

Zheng, Z., Cai, Y., Wang, F., & Gu, B. (2009). Below-replacement fertility and childbearing intention in Jiangsu Province, China. Asian Population Studies, 5(3), 329–347.

Acknowledgments

This article is supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation General Project (71173099) and National Natural Science Foundation Youth Project (70903002), supported in part by Trans-Century Training Program Foundation for the Talents of Humanities and Social Science by the State Education Commission (NCET-11-0228). We also thanks Yun Yu (graduate student in School of Humanity and Social Science, Nanjing University of Science and Technology) for making substantial contributions for translation and Yan Li (Zhejiang University) for making substantial contributions for data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, Y., Yi, Y. & Sun, Q. The Impact of Migration on Fertility under China’s Underlying Restrictions: A Comparative Study Between Permanent and Temporary Migrants. Soc Indic Res 116, 307–326 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0280-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0280-4