Abstract

Purpose

Patients’ values for health outcomes are central to treatment decisions in bladder cancer (BCa). An instrument incorporating the expressed preferences of BCa patients, as measured by utility, can inform clinical guidelines, resource allocation and policy decisions. Developing this instrument requires a formal conceptual framework summarizing the important domains comprising global health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in BCa.

Methods

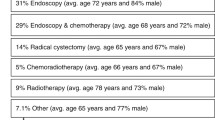

We performed a systematic literature search on the HRQOL effects of BCa and its treatments to generate initial items in Medline, Embase, CINAHL and PsychInfo up to January 2013. Thematic synthesis was used to group related items into overarching themes (domains) and create a provisional conceptual framework. In focus groups, 12 BCa experts and 47 BCa patients with diverse clinical histories generated further items to inform the final conceptual framework.

Results

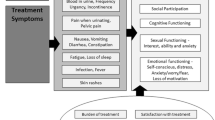

We retrieved 1,275 citations and reviewed 170 full-text publications. One hundred and sixty-nine items were extracted into 12 domains. Study investigators used the findings from the focus groups to confirm the domains and condense the list to 83 clinically important items. Functional limitations in work, travel, social interaction and sleep lowered HRQOL in many domains. The final conceptual framework included BCa-specific (urinary, sexual, bowel, body image) and generic domains (pain, vigor, social, psychological, sleep, functional, family relationship, medical care relationship).

Conclusions

A conceptual framework including 12 domains can serve as the foundation for the development of an instruments measuring global HRQOL in BCa and in particular, one that can measure patient preferences and generate utilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Jemal, A., Bray, F., Centre, M., Ferlay, J., Ward, E., & Forman, D. (2011). Global cancer statistics. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 61, 69–90.

Fokdal, L., Høyer, M., Meldgaard, P., & von der Maase, H. (2004). Long-term bladder, colorectal, and sexual functions after radical radiotherapy for urinary bladder cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology, 72(2), 139–145. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2004.05.006.

Efstathiou, J. A., Bae, K., Shipley, W. U., Kaufman, D. S., Hagan, M. P., Heney, N. M., et al. (2009). Late pelvic toxicity after bladder-sparing therapy in patients with invasive bladder cancer: RTOG 89-03, 95-06, 97-06, 99-06. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27(25), 4055–4061. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5776.

Grossman, H. B., Natale, R. B., Tangen, C. M., Speights, V. O., Vogelzang, N. J., Trump, D. L., et al. (2003). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine, 349(9), 859–866. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022148.

Nieder, A. M., Brausi, M., Lamm, D., O’Donnell, M., Tomita, K., Woo, H., et al. (2005). Management of stage T1 tumors of the bladder: International Consensus Panel. Urology, 66(6), 108–125.

David, K. A., Milowsky, M. I., Ritchey, J., Carroll, P. R., & Nanus, D. M. (2007). Low incidence of perioperative chemotherapy for stage III bladder cancer 1998–2003: A report from the National Cancer Data Base. The Journal of Urology, 178(2), 451–454. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.101.

Drummond, M. F., Sculpher, M. J., Torrance, G. W., O’Brien, B. J., & Stoddart, G. L. (2005). Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes (3rd ed., p. 379). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Froberg, D. G., & Kane, R. L. (1989). Methodology for measuring health-state preferences—I: Measurement strategies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 42(4), 345–354.

Torrance, G., & Feeny, D. (1989). Utilities and quality-adjusted life years. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health, 5, 559–575.

Blinman, P., King, M., Norman, R., Viney, R., & Stockler, M. R. (2012). Preferences for cancer treatments: An overview of methods and applications in oncology. Annals of Oncology, 23(5), 1104–1110. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr559.

Gacci, M., Saleh, O., Cai, T., Gore, J. L., D’Elia, C., Minervini, A., et al. (2013). Quality of life in women undergoing urinary diversion for bladder cancer: Results of a multicenter study among long-term disease-free survivors. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11(1), 43. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-11-43.

Froberg, D. G., & Kane, R. L. (1989). Methodology for measuring health-state preferences—II: Scaling methods. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 42(5), 459–471.

Dolan, P., Gudex, C., Kind, P., & Williams, A. (1995). A social tariff for EuroQol: Results from a UK general population survey (No. Discussion paper 138).

Tomlinson, G., Bremner, K. E., Ritvo, P., Naglie, G., & Krahn, M. D. (2012). Development and validation of a utility weighting function for the patient-oriented prostate utility scale (PORPUS). Medical Decision Making, 32(1), 11–30. doi:10.1177/0272989X11407203.

Programme on Mental Health—WHOQOL Measuring Quality of Life. (1997). World health (pp. 1–13). Geneva, Switzerland.

Kastner, M., Tricco, A. C., Soobiah, C., Lillie, E., Perrier, L., Horsley, T., et al. (2012). What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(1), 114. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-12-114.

Krahn, M., Ritvo, P., Irvine, J., Tomlinson, G., Bezjak, A., Trachtenberg, J., et al. (2000). Construction of the patient-oriented prostate utility scale (PORPUS): A multiattribute health state classification system for prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(9), 920–930.

Aaronson, N. K., Calais da Silva, F., Yoshida, O., van Dam, F. S., Fossa, S. D., Miyakawa, M., et al. (1986). Quality of life assessment in bladder cancer clinical trials: Conceptual, methodological and practical issues. Progress in Clinical and Biological Research, 221, 149–170.

Mansson, A., Johnson, G., & Mansson, W. (1988). Quality of life after cystectomy comparison between patients with conduit and those with continent caecal reservoir urinary diversion. British Journal of Urology, 62(3), 240–245.

Faithfull, S. (1995). “Just grin and bear it and hope that it will go away”: Coping with urinary symptoms from pelvic radiotherapy. European journal of cancer care, 4(4), 158–165.

Henningsohn, L., Wijkstrom, H., Steven, K., Pedersen, J., Ahlstrand, C., Aus, G., et al. (2003). Relative importance of sources of symptom-induced distress in urinary bladder cancer survivors. European Urology, 43(6), 651–662.

Gilbert, S. M., Dunn, R. L., Hollenbeck, B. K., Montie, J. E., Lee, C. T., Wood, D. P., et al. (2010). Development and validation of the Bladder Cancer Index: A comprehensive, disease specific measure of health related quality of life in patients with localized bladder cancer. The Journal of Urology, 183(5), 1764–1769.

Fellin, G., Graffer, U., Bolner, A., Ambrosini, G., Caffo, O., & Luciani, L. (1997). Combined chemotherapy and radiation with selective organ preservation for muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma. A single-institution phase II study. British Journal of Urology, 80(1), 44–49.

Roychowdhury, D. F., Hayden, A., & Liepa, A. M. (2003). Health-related quality-of-life parameters as independent prognostic factors in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21(4), 673–678.

Palapattu, G. S., Haisfield-Wolfe, M. E., Walker, J. M., BrintzenhofeSzoc, K., Trock, B., Zabora, J., et al. (2004). Assessment of perioperative psychological distress in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. The Journal of Urology, 172(5 Pt 1), 1814–1817.

Biermann, C. W., Schmidt, C., & Kuchler, T. (1995). Development of a life quality questionnaire in bladder cancer surgery. British Journal of Urology, 76(3), 412–413.

Thulin, H., Kreicbergs, U., Wijkstrom, H., Steineck, G., & Henningsohn, L. (2010). Sleep disturbances decrease self-assessed quality of life in individuals who have undergone cystectomy. The Journal of Urology, 184(1), 198–202.

Nordstrom, G., Nyman, C. R., & Theorell, T. (1992). Psychosocial adjustment and general state of health in patients with ileal conduit urinary diversion. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology, 26(2), 139–147.

Sengelov, L., Frolich, S., Kamby, C., Jensen, N. H., & Steven, K. (2000). The functional and psychosocial status of patients with disseminated bladder cancer. Urologic Oncology, 5(1), 20–24.

Kitamura, H., Miyao, N., Yanase, M., Masumori, N., Matsukawa, M., Takahashi, A., et al. (1999). Quality of life in patients having an ileal conduit, continent reservoir or orthotopic neobladder after cystectomy for bladder carcinoma. International Journal of Urology, 6(8), 393–399.

Rabow, M., Evans, C., Weinberg, V., & Miller, B. (2011). Symptom burden for patients with bladder cancer and their family caregivers: Preliminary results (753). Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(1), 304–305.

Colwell, J. C. (2005). Dealing with ostomies: Good care, good devices, good quality of life. The Journal of Supportive Oncology, 3(1), 72–74.

Botteman, M. F., Pashos, C. L., Redaelli, A., Laskin, B., & Hauser, R. (2003). The health economics of bladder cancer: A comprehensive review of the published literature. Pharmacoeconomics, 21(18), 1315–1330.

Gilbert, S. M., Wood, D. P., Dunn, R. L., Weizer, A. Z., Lee, C. T., Montie, J. E., et al. (2007). Measuring health-related quality of life outcomes in bladder cancer patients using the Bladder Cancer Index (BCI). Cancer, 109(9), 1756–1762. doi:10.1002/cncr.22556.

Cookson, M. S., Dutta, S. C., Chang, S. S., Clark, T., Smith, J. A. J., & Wells, N. (2003). Health related quality of life in patients treated with radical cystectomy and urinary diversion for urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: Development and validation of a new disease specific questionnaire. The Journal of Urology, 170(5), 1926–1930.

Jefford, M., Karahalios, E., Pollard, A., Baravelli, C., Carey, M., Franklin, J., et al. (2008). Survivorship issues following treatment completion–results from focus groups with Australian cancer survivors and health professionals. Journal of Cancer Survivorship: Research and Practice, 2(1), 20–32. doi:10.1007/s11764-008-0043-4.

Helman, C. G. (1995). The body image in health and disease: Exploring patients’ maps of body and self. Patient Education and Counseling, 26, 169–175.

Mechanic, D. (2004). In my chosen doctor i trust: And that trust transfers from doctors to organisations. British Medical Journal, 329(7480), 1418–1419.

Rasmussen, D. M., & Elverdam, B. (2008). The meaning of work and working life after cancer: An interview study. Psycho-Oncology, 17, 1232–1238. doi:10.1002/pon.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by an operating Grant from The Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors would like to thanks Kirstin Boehme for her assistance reviewing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Search strategies for conceptual framework and item generation

Appendix 2: Script for expert focus group—item generation

Group leader (NP): Thank you for agreeing to participate in this genitourinary, BCa expert panel today. Let me introduce the members of the group. Dr. XX, specialty YY, from University VV. My name is Nathan Perlis. I am a urology resident at University of Toronto and a Masters student at the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation. I am one of the co-investigators in this study. This is ZZ he/she is the research assistant working on our project.

The objective of our study is to design a measurement instrument that can accurately measure quality of life for patients with BCa, particularly focusing on how quality of life issues affect BCa patients when making decisions about their care. This instrument is intended for use on all patients with BCa regardless of disease severity, age, or treatment history.

You have all been invited to this focus group because of your extensive experience working with patients with BCa. Likely, you have all helped council patient through difficult decisions regarding care where quality of life was an important consideration. At this stage of questionnaire design we are trying to consider as many items as possible that may be important to BCa patients and their quality of life. By the end of today’s session we hope to have a long-list of items that can later be pared down to the most important to be included in our instrument.

Your participation in this focus group is entirely voluntary. If at any time you would like to withdraw you can stop participating. I will be transcribing the items that you suggest during this session on a board for everyone to see and the RA will be taking notes. Each of your identities will be anonymous and the items generated will not be linked with particular specialists. I am also audio recording the meeting. I will use the audiotape only to clarify my notes, and once I am satisfied with the transcription the tapes will be deleted.

Are there any questions so far?

Would anyone no longer like to participate?

Let us start with a general question: How do you think quality of life is diminished for patients with BCa?

Items will be written on chalkboard. We will be as inclusive as possible—items will be considered unique as long as any specialist considers them separate (i.e., Loss of sensation and numbness).

When no new items are being suggested we will prompt the group further by presenting a list of items that we generated prior by literature search:

Here is a list of items that we generated from the literature that have been used in previous quality of life instruments for patients with BCa. Does this list prompt any new items that you can offer?

Once no new items are generated we will conclude:

Thank you again for your attendance. We will inform you soon regarding possible dates for the next expert meeting where we will review the preliminary instrument.

Appendix 3: Patient focus group and phone interview script

Hello everyone, thank you very much for attending this focus group today. My name is Nathan Perlis. I am a doctor currently training in urology and attaining a master’s degree in clinical epidemiology at University of Toronto. This is XXX the research assistant on this project. First, I would like to thank you for agreeing to participate in this study. If any of you have any questions about the study or need any clarification please ask at any point. If at any time you feel that you would no longer like to participate in the study that is fine. Participation is completely voluntary. We thank you for taking time to attend this session.

As you have already read in the consent form, this study concerns quality of life in BCa. You are being asked to take part in this research study because you have BCa and have experienced its affects on quality of life. The aim of this study is to develop a new questionnaire to measure quality of life in all BCa patients.

This study will not benefit you specifically but it should advance knowledge about issues related to the treatment of BCa. There are no expected risks of participation in this study, other than feelings of stress or embarrassment. You may refuse to answer any questions should you so choose.

The objective of our study is to design a measurement instrument that can accurately measure quality of life for patients with BCa, particularly focusing on how quality of life issues affect BCa patients when making decisions about their care. This instrument is intended for use on all patients with BCa regardless of disease severity, age, or treatment history.

At this early stage of questionnaire development we are trying to consider as many items as possible that may be important to you and your quality of life. By the end of today’s session we hope to have a long-list of items that can later be pared down to the most important items to be included in the instrument.

Everything that you say today will be kept in strict confidence. We will be taking notes, but your names will not be linked to any comments. We will also be audio recording and transcribing the interview but names of participants will not be transcribed and the audiotapes will be destroyed once they are transcribed. We ask that any comments that other participants make today be treated with strict confidence.

Are there any questions?

Can I clarify anything so far?

Is there anyone that would no longer like to participate?

We will start the question and answer period now.

What are the most significant ways in which BCa affects your quality of life?

Try and consider times during your illness where you were faced with a difficult decision about therapy for BCa. Were there quality of life issues that you were concerned about? How did those affect your decision making?

Thank you for those detailed responses. We would like you now to consider some specific areas that may or may not have been covered already.

How does BCa affect your physical health?

How does BCa affect your self-care?

How does BCa affect your work?

How does BCa affect your household activities?

How does BCa affect your social activities?

How does BCa affect your hobbies?

How does BCa affect your relationships?

How does BCa affect your ability to be sexually intimate?

Thank you again for participating in this session. We will be contacting you all to arrange follow-up interviews.

Appendix 4: Unabridged item list from literature search

-

1.

Frequency

-

2.

Dysuria

-

3.

Painful urination

-

4.

Urgency

-

5.

Nocturia

-

6.

Sleep disturbance

-

7.

Bone pain from metastatic disease

-

8.

Pelvic pain from metastatic disease

-

9.

Incontinence

-

10.

Pain (general)/aches pains

-

11.

Hematuria

-

12.

Incomplete emptying

-

13.

Decreased urinary stream

-

14.

Nausea

-

15.

Fatigue

-

16.

Dyspnea

-

17.

Insomnia

-

18.

Infection

-

19.

Lymphoedema

-

20.

Urinary control

-

21.

Nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy

-

22.

Anorexia from chemo

-

23.

Weight loss fro chemo

-

24.

Fatigue and malaise from chemo

-

25.

Alopecia from chemo

-

26.

Diarrhea from chemo

-

27.

Mouth soreness from chemo

-

28.

Sleep disturbance from chemo

-

29.

Serious chemo toxicity—septicemia/organ failure

-

30.

Hematologic—anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, neutropenia

-

31.

Infertility from chemo

-

32.

GI symptoms/rectal/diarrhea/blood

-

33.

Abdominal bloating

-

34.

Difficulty or apprehension about catheterizing a pouch/stoma/neobladder

-

35.

Continent reservoir advantage intact skin, no stoma, no appliance

-

36.

Pain/soreness at stoma

-

37.

Ileal conduit—leakage/neobladder nocturnal leak

-

38.

Chronic urinary infections

-

39.

Contracted bladder

-

40.

Renal failure and electrolyte disturbances

-

41.

Skin excoriation

-

42.

Sexual impotence

-

43.

Foul odor from stoma/urine/gas

-

44.

Incontinence with neobladder/leakage stoma

-

45.

Metabolic abnormality—b12 deficiency, osteoporosis, acidosis

-

46.

Food intolerance

-

47.

Appetite loss

-

48.

Frequent stoma emptying

-

49.

Urinary bother

-

50.

Feel urostomy is foreign

-

51.

Fatigue and malaise

-

52.

Radiation cystitis

-

53.

Radiation proctitis

-

54.

Radiation enteritis

-

55.

Diarrhea

-

56.

GI fistula

-

57.

Contracted bladder

-

58.

Infertility—increased FSH

-

59.

Hematuria

-

60.

Body awareness

-

61.

Urinary frequency

-

62.

Dysuria

-

63.

Hematuria

-

64.

Mucus secretion

-

65.

Nausea

-

66.

Fatigue

-

67.

Chills

-

68.

Joint pain

-

69.

Fever

-

70.

Pain secondary to IV therapy

-

71.

Time required to get the iv course complete

-

72.

Able to have sex

-

73.

Impotence/ED

-

74.

Fear of intimacy

-

75.

Decreased libido

-

76.

Decreased sexual pleasure

-

77.

Psychogenic ED

-

78.

Painful intercourse

-

79.

Genital pain in women with intercourse

-

80.

Satisfied by sexual life

-

81.

Level of “sexuality”

-

82.

Intercourse frequency

-

83.

Disrupted vaginal anatomy

-

84.

Altered sensation

-

85.

Importance of getting back to “normal” or baseline lifestyle

-

86.

Demand of treatment regimes limit ability to maintain social contacts

-

87.

Fear of leaking limits social interaction

-

88.

Fear of being burden to others

-

89.

Embarrassment of symptoms

-

90.

Hesitancy in asking for support

-

91.

Family withdrawal of contact

-

92.

Hobbies and interests maintained or restricted

-

93.

Position in family

-

94.

Generally altered marital/partner relationship/family

-

95.

Generally altered relationships with friends

-

96.

Embarrassed public bathing, swimming, etc., from stoma

-

97.

Comfortable discussing condition with friends

-

98.

Afraid to be far from toilet

-

99.

Reduction in free time

-

100.

Holidays/traveling

-

101.

Difficulty meeting new people

-

102.

Self-care activities

-

103.

Mobility

-

104.

Physical activity

-

105.

Role activity

-

106.

Unfit to work

-

107.

Physically unwell

-

108.

Tired

-

109.

Generally ill

-

110.

Vitality/energetic

-

111.

Maintaining independence

-

112.

Forced to spend time in bed

-

113.

Exercise

-

114.

Depression

-

115.

Anxiety

-

116.

Physical and emotional burden of repeat procedure

-

117.

Fear of death

-

118.

Loss of love

-

119.

Support from spouse

-

120.

Loss of security

-

121.

Generally altered mental status

-

122.

Irritability

-

123.

Despair with urinary leakage

-

124.

Loneliness

-

125.

Worry treatment won’t work

-

126.

Worry treatment will limit ability to work

-

127.

Trauma from genital surgery

-

128.

Loss of self-esteem

-

129.

Coping

-

130.

Tense

-

131.

Accepting diagnosis

-

132.

Restless

-

133.

Find life meaningless

-

134.

Changed outlook on life

-

135.

Distress of false positive results

-

136.

Distress due to waiting time for results of tests

-

137.

Feel safe or not

-

138.

Altered relationship to pain

-

139.

General psych distress

-

140.

Somatization

-

141.

Uncertainty

-

142.

Loss of body image

-

143.

Ability to conceal stoma

-

144.

Catheterizing in public

-

145.

Feel undesirable when family or friends see stoma

-

146.

Accepting the stoma

-

147.

Contempt

-

148.

Happiness

-

149.

Spiritual life/religion

-

150.

Sense of inner peace

-

151.

Reason to be alive

-

152.

Coping strategies

-

153.

Interpersonal manner of healthcare providers

-

154.

Technical quality of healthcare delivery

-

155.

Efficacy of medical care

-

156.

Availability of stoma nurse

-

157.

Knowledge of ward nurse about stoma needs

-

158.

Sufficient and quality of info about disease and treatment and satisfaction

-

159.

Nursing efforts to develop self-care

-

160.

Feeling like nothing can be done to relive symptoms

-

161.

Embarrassed to “make a fuss” or tell MD about symptoms so as not to jeopardize Rx

-

162.

Knowing who to contact and what to do when side-effects occur

-

163.

Talking with patient that has undergone same treatment

-

164.

Anxiety about not knowing ahead of time which urinary reconstruction will be performed

-

165.

Satisfied with type of diversion received

-

166.

Contact with hospital

-

167.

Decrease “in patient” hospital stay without surgery

-

168.

Provision of nurse-led follow-up care increases pt satisfaction

-

169.

Physician effort in including patient in decision making

Appendix 5: Twenty most frequent items relating HRQOL and BCa in the literature

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perlis, N., Krahn, M., Alibhai, S. et al. Conceptualizing global health-related quality of life in bladder cancer. Qual Life Res 23, 2153–2167 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0685-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0685-9