Abstract

Despite the historical prevalence of single motherhood in Latin America and its rise in recent years, there is limited knowledge on the magnitude and consequences of father absence as experienced by children. Using a nationally representative sample from the 2002 Guatemalan Reproductive Health Survey, this study provides unprecedented documentation on the national prevalence of children’s separate living arrangements from their biological fathers and nonresident fathers’ paternity establishment and child support payments. Using random-intercept models, this study further demonstrates that father absence has a negative effect on the school enrollment of indigenous children of both sexes and Ladino male children. Increased poverty in father-absent households explains a smaller proportion of this adverse effect on indigenous children, suggesting that their fathers, when present, play a stronger social, rather than economic, role compared to their Ladino counterparts. Finally, child support payments attenuate the negative effects of father absence, particularly among Ladino male children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Single motherhood has been historically common in Latin America because of the relatively high incidence of un-partnered childbearing and equally high dissolution rates, especially among non-marital consensual unions, when compared to other less-developed countries. Recent studies offer evidence that single motherhood has become even more common over the past several decades (Ali et al. 2003; Arriagada 2002), suggesting that an ever larger proportion of children are growing up in father-absent households. The negative consequences of father absence for children shown in earlier studies include poor academic performance, lower overall educational attainment, psychological and behavioral problems, and early marital and non-marital childbearing (for a recent review, see Sigle-Rushton and McLanahan 2004). However, much of the evidence comes from the U.S. and other developed nations, and the fortunes of Latin American children brought up in single-parent households are less well known despite its increasing significance to the region.

This research provides both descriptive and analytic documentations of father absence, using a large, nationally representative sample from Guatemala. Guatemala is a highly segmented society with one of the largest income disparities in the world. Poverty is disproportionately concentrated among indigenous people, who constitute approximately half of the Guatemalan population (Bossen 1984; Hall and Patrinos 2006). Mestizos, or locally called “Ladinos,” who are mixed-race individuals whose roots are traced to indigenous people and Spanish conquerors, have monopolized major commercial, cultural, and political positions in national society, while ascribing the indigenous people’s poverty to their “cultural and biological inferiority” (Casaus Arzu 1999; Nelson 1998). Indigenous people are isolated in rural and often remote areas, which severely hinder them from attaining higher socioeconomic status. This geographic isolation, along with the extremely high rates of community endogamy, has helped indigenous people maintain strong community ties, an ancestry-based identity, and cultural autonomy to the present.

A growing body of work has begun to establish the significant roles of race and ethnicity in family arrangements and father–child relationships (Brooks-Gunn and Markman 2005; Hofferth 2003; King et al. 2004; McLanahan 1985; Parke and Buriel 1998; Schwartz and Finley 2005). Family structures may be of particular interest to students of social stratification because their changes, patterns, and consequences may be closely associated with race and ethnicity and constitute important mechanisms in reproducing racial and ethnic inequalities (McLanahan and Percheski 2008). Guided by insightful ethnographic accounts of two distinct patriarchies by ethnicity in Guatemala (Bastos 1999; Maynard 1974), this study attempts to compare indigenous and Ladino children’s experiences of father absence and to determine whether the ethnic differences in the family structure and father–child relationship mitigate or reinforce ethnic inequality in Guatemala. Two steps are taken toward this goal. First, I document the prevalence of father absence in children’s lives by ethnicity. Second, I assess the implication of father absence on children’s welfare measured by school enrollment status. Particularly, I attempt to determine the relative importance of the economic versus the social roles that absent fathers might have played if they had shared the household with their children (Hofferth 2003).

To my knowledge, this study is the first to investigate both the prevalence and the consequences of father absence as experienced by children in Guatemala based on a nationally representative sample. This unprecedented documentation of father absence is made possible by the 2002 Guatemalan National Survey of Maternal and Child Health (ENSMI), which incorporated new, unique questions on co-resident status with biological fathers and the current school enrollment status for all the living children of the respondents in the sample as well as paternity establishment and economic support for children not residing with their fathers. The study takes full advantage of these rich data and provides important insights into the profile of fatherless children and the significance of ethnicity in father absence in Guatemala.

Father Absence in Latin America: Past Studies

The legacy of patriarchal ethos that the conquerors brought from pre-industrial Spain has had an important role in family arrangements among Ladinos, the descendants of these conquerors (Arriagada 2002). This traditional model of patriarchy idealizes the father’s role as the protector and sole provider of his family, which in turn legitimizes his authority in the household and establishes his masculine identity. In quasi-subsistence agriculture, which dominated the economy in the region, Ladino fathers were the main breadwinners and managers of family production enterprises (Kaztman 1992). However, modernization and the concomitant economic instability in Latin America have made this patriarchal male role more difficult to fulfill. Rapid industrialization and urbanization have led to a surge in the number of unemployed males and left many in a precarious labor market situation (CEPAL 1995). Urban residence and the increased exposure to mass media have fostered stronger aspirations for a higher standard of living, which many urban migrant males on meager wages were incapable of achieving for their families. These developments have been accompanied by an increase in female labor force participation and incomes, which further reduced the relative economic contribution of fathers and eroded the Ladino males’ authority in the household. As a result, unions have become more unstable and difficult to form among single Ladino males. However, fatherhood still remains an important public display and proof of male virility and “responsibility” (De Vos 1998) and one of the few avenues to sustain masculine identities among lower-class Ladino men (Bastos 1997; Fuller 2000; Viveros Vigoya 2001). Consequently, sexuality and reproduction are increasingly decoupled from family formation among Ladinos, and a growing number of children are “abandoned” by their biological fathers.

Ethnographic studies on men and the constructs of masculinity in Latin America caution against stereotyping Latin American men as “irresponsible husbands and fathers.” They have demonstrated that men do participate in parenting (Gutmann 1996) and consider family life as an important element of their masculine identities (Henao 1994) and although men’s abandonment of families did not cease, it is now questioned (Gutmann 2005). However, others also argue that as the gendered division of labor continues to dominate in the household, assigns fathers authoritative figures in the household, and exempts them from emotional investment in their children, fathers, although they may be present in the household, are still hesitant to actively adopt an affectionate role, especially toward their daughters, reinforcing the great distance between fathers and their children (Bronstein 1984; de Keijzer 1998; Fonseca 1998; Fuller 2000).

On the contrary, indigenous patriarchy in Guatemala has been often characterized by stronger paternal involvement and a more egalitarian economic partnership (Bastos 1999; Maynard 1974). In this traditional cultural model, the more important source of fathers’ authority in indigenous households is associated with their commitments to their families and communities, where they have significant social and ceremonial roles rather than the satisfactory fulfillment of their breadwinning role. The economic responsibility to sustain the household is shared between husbands and wives, and female labor force participation has always been more common in the indigenous household. Such an economic partnership strengthens the union, rather than undermines it (Cabrera Pérez-Armiñán 1992; Glitenberg 1994; Paul 1974). Furthermore, indigenous men unequivocally eschew Ladino “promiscuity” (Smith 1995), and women are not perceived as men’s means to prove their maleness, but are highly respected and valued as biological and cultural reproducers of Mayan cultures. The stronger emphasis on the social, rather than the economic, role for indigenous men and the lack of disjuncture between sexuality and reproduction and family organization together make the traditional family organization more resistant to economic crisis as compared to the Ladino patriarchy (Bastos 1999).

Parallel to the series of studies on men as fathers, extensive scholarly attention has been garnered by the “feminization of poverty,” or the potential impoverishment of a growing number of single mothers in Latin America (Buvinic and Gupta 1997; Chant 2003; De Vos and Arias 1998; Marcoux 1998). Unlike the increased incidence of poverty among female-headed households elsewhere, recent quantitative studies from Latin America demonstrate that single mothers are not necessarily the poorest of the poor, and their socioeconomic status is heterogeneous (CEPAL 2001; Fuwa 2000; Quisumbing et al. 2001). Single mothers are more likely to live in an extended family, have a smaller number of children, and be engaged in remunerated jobs, all of which safeguard them from severe poverty and compensate for the lack of a male partner’s income (González de la Rocha 1999a; Safa 1999; Waternberg 1999). Furthermore, many women and their children are actually better off alone because the absence of male partners enables single mothers to make decisions for themselves (Feijoó 1999) and allows a more balanced intra-household resource allocation (Chant 1997; Engle and Breaux 1998; Varley 2001). In addition, it is claimed that more women are taking the initiative in union dissolution than in the past (Chant 1997; González de la Rocha 1999b; Safa 1999), and a non-negligible fraction of unmarried single mothers do not demand the fathers’ acknowledgement of the paternity of their children (Budowski and Bixby 2003).

Although there is a significant number of quantitative and qualitative studies on the absence of father/husband in the household from both women’s and men’s perspectives, children’s experiences of father absence in Latin America has not been the focus of research (Barker 2003). While some studies have found no, or even protective effects of single motherhood (versus being raised in two-parent households) on children’s welfare as measured by height for age and school enrollment in Guatemala and other Latin American countries (Desai 1992; Engle 1995; Yoshioka 2006), the evidence to date is far from being conclusive or sufficient. In particular, the role of ethnicity has not been given attention. From the literature on ethnic differences in the roles attached to fathers, several hypotheses regarding the role of ethnicity in father absence can be generated. According to research on the ethnic difference in the way family organizations react to the force of modernization, it is predicted that indigenous children are more likely to live with their biological fathers than Ladino children. In contrast to the U.S. where minority children are more likely to be found in single-parent households and therefore less likely to receive the benefits of growing up with two parents than their white counterparts (Kennedy and Bumpass 2007), ethnic differences in children’s living arrangements in Guatemala are expected to mitigate, rather than exacerbate, the ethnic hierarchical structure. Second, since the economic role is described as less important for the indigenous than for the Ladino fathers, it is hypothesized that a smaller proportion of the expected negative effect of the absence of the biological father among indigenous children is attributed to the increased poverty in the father-absent household than to the lack of socio-emotional support from the father. On the other hand, a larger proportion of the negative effect of father absence among Ladino children is attributed more to poverty than to the lack of a paternal caregiver. Elsewhere, empirical evidence on the differential effects of father absence according to their children’s sex has been inconsistent (Lundberg et al. 2007; McLanahan 1985; Sigle-Rushton and McLanahan 2004). The socio-emotional distance between fathers and daughters among mestizos, as suggested in Latin American literature, might diminish the importance of a father’s presence among girls. Thus, father absence is expected to have an even smaller negative effect among Ladina girls.

Limitations

Two important limitations need to be acknowledged. The first concerns the lack of information about the father’s characteristics, particularly his ethnic identification. Taking into account of Guatemala’s extremely high ethnic endogamy rate—one of the highest community-endogamy rates in the world among indigenous people (Smith 1995)—it is reasonable to assume that the ethnicity of fathers, particularly those present in the household, is the same as that of the mothers for the majority of the cases. In the logistic regression used to assess the consequence of father absence, the coefficient estimate of father absence, or the difference in the likelihood of school enrollment between children in two-parent households, where the ethnicity of these parents is reasonably assumed to be the same, and children in father-absent households, regardless of ethnicity, represents the disadvantage of not having fathers of the same ethnicity in the household. The size of the difference may be underestimated, rather than overestimated, to the extent that this assumption does not hold. Therefore, this study elucidates ethnic differences in the importance and the type of father’s role, which is fulfilled by co-resident fathers of the same ethnicity, or which would have been fulfilled by absent fathers if they had had the same ethnicity as that of the mothers and co-resided with the children. On the other hand, because of the potentially higher instability of inter-ethnic unions, particularly in Guatemala where a rigid ethnic boundary/hierarchy that exists (Pebley et al. 2005), the assumption that the absent fathers have the same ethnicity as the mothers may be less likely to be valid and the likelihood of paternity establishment and economic support payments may be affected by whether or not the nonresident fathers are of the same ethnicity as the mothers. Implications will be further discussed later.

The second limitation concerns the inference of causality. The analyses are based on the fathers’ co-resident status and the school enrollment status of children at the time of the survey. The timing of mothers’ union dissolution or fathers’ death (if they have ever been in unions) and the timing of children’s exit from school (if they have ever been enrolled in school) are not considered due to the lack of data. The association between the children’s current living arrangement and the current school enrollment may be partially caused by endogeneity: mothers who are likely to be single are also likely to fail to enroll their children in school because of their unobserved characteristics. By using random-intercept models, this study is able to reduce this bias in the estimates, thereby broadly capturing the independent and negative association between father absence in the children’s households and school enrollment; however, the mothers’ union history and the children’s school enrollment history are required to better establish causality.

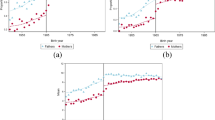

School Enrollment in Guatemala

In a less-developed country like Guatemala where agriculture dominates the economy, young children are often an important labor force in the household; thus enrolling them in school reflects substantial resources spared for, and a high level of parental commitment to, these children. A cross-national comparison indicates that Guatemala has a comparable net enrollment rate—94%—of primary education among children aged 7–12 years in Latin America; however, the net enrollment rate of secondary education among children aged 13–18 years is 35%, the lowest figure in the region (UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2008), even though the current law in Guatemala obliges all children to complete first 3 years of secondary education. Education is a powerful and important indicator of children’s long-term socioeconomic well-being and is one of the most important mechanisms by which ethnic inequality is created and reproduced over generations in Guatemala (Hallman et al. 2005). Figure 1 illustrates this: indigenous children are consistently less likely to be enrolled in school than Ladino children. The ethnic difference is more substantial among girls, particularly at older ages, probably because of their early childbearing (Lindstrom 2003), which conflicts with school attendance (Lloyd and Mensch 2008). Only 27% of indigenous girls at the age of 15 are enrolled in school while 68% of their Ladina counterparts attend school. The corresponding figures are 55 and 68% for indigenous and Ladino boys, respectively, highlighting the indigenous girls’ double burden of ethnicity and gender. This study further examines whether father absence adds to, or interacts with, ethnicity in its potential effects on children’s school enrollment.

Data and Methods

Data

The data for this study are drawn from the fourth version of Reproductive/Demographic Health Surveys conducted by the Guatemalan Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance (MSPAS) with technical assistance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta. It is a nationally representative sample of 9,155 women and 2,538 men. It employed a multi-stage cluster sample design based on the census tracts constructed for the 1994 Census, which define “communities” for the purpose of the present analysis. For the female sample used in this study,Footnote 1 one woman aged 15–49 years was randomly selected from each of the 30 randomly selected households per cluster. The final sample had 373 clusters. The response rate was 94% (MSPAS 2003).

The analytic samples are based on children of all women who were interviewed. However, children whose mothers were currently in either consensual or legal marital unions but did not reside with their male partners are excluded. This is because the reasons for such separate living arrangements cannot be determined from the data, and they can be due not only to the fathers’ temporary labor migration but also to the process of union dissolution. Children who did not reside with their mothers at the time of the survey are excluded because information on these children’s living arrangements is not available from the data. Out of 20,646 children in the sample who were 15 years old or younger, a total of 18,514 childrenFootnote 2 of 6,135 mothers constitute the first analytic sample for the descriptive analysis of the prevalence of father absence. Out of the 10,294 children aged 7Footnote 3–15 years, 7,863 children of 3,702 mothers constitute the second analytic sample and are used in the multivariate analysis of school enrollment.Footnote 4 Sampling weights were applied throughout the analyses to correct for the children’s unequal probabilities of selection.

Modeling Strategy and Variables

To estimate the effect of father absence on children’s school enrollment status, I use random-intercept models, or multi-level logistic regression models, where the second level is introduced for mothers. Random-intercept models take advantage of detailed information on multiple children of the same mother in the 2002 ENSMI. They reduce bias in the coefficient estimates of father absence by capturing and purging the estimation of the mother’s measured and unmeasured characteristics constant across these children and correcting for the potential correlation between their propensities to become single mothers and to fail to enroll their children in school (Ashenfelter and Krueger 1994; Wooldridge 2009). Residual variance captures the similarity among children of the same mothers because of their shared but unobserved characteristics.

To clarify the mechanism through which father absence in children’s households affects current school enrollment, I use a series of nested models. Along with other appropriate controls, the first model contains one main independent variable, a dichotomous indicator of father absence, for which children who live away from their biological fathers are coded 1, and those who live with both the parents are coded 0. The outcome variable, i.e., children’s school enrollment status, is also measured as a dichotomous indicator, coded 1 when the child is enrolled in school in the year 2002, and 0 otherwise. In this model, I test the significance of the interaction terms between father absence and the child’s female sex to examine whether girls are less disadvantaged by father absence than boys.

Household economic status is added to the second model to examine whether, and how much of, the negative effect of father absence, which will be shown, is explained by increased poverty in father-absent households. I expect to see a smaller reduction in the negative effect of father absence among indigenous children because their fathers’ economic role is hypothesized to be less important than that of their Ladino counterparts. As household income was not included in the 2002 ENSMI, a proxy index for household economic status is created based on the ownership of assets and housing characteristics and quality.Footnote 5 The assets that I consider are laundry machines, cars, and other items that are likely to represent the household economic standing. Housing characteristics include toilet facilities and availability of electricity. Materials that made up walls, roofs, and floors are evaluated by using three-level scale that ranges from low to high (Arias and De Vos 1996). I use principal-components analysis to determine the weights for each of these items, characteristics, and levels (Filmer and Pritchett 2001), and the sums of the weighted scores are then rescaled to a range of 0–1.

Finally, I create two dummy variables for children who live away from their biological fathers and receive economic support from these fathers, regardless of the amount, and for children who live away from their fathers and do not receive economic support. The reference category is children in two-parent households. This third and final model attempts to assess whether the negative effect of father absence is attenuated by the nonresident father’s child support payments.

To facilitate the comparisons of the coefficients among these nested regression models, the variance of the latent Y variable is fixed. This is because the coefficient estimates may otherwise change even when variables added to the model are not correlated with father absence (Mare 2006). A Y*-standardized coefficient indicates the expected change expressed in standard deviations of the latent outcome variable for a one-unit change in the given independent variable. All models include the same set of control variables. Most importantly, I control for the number of siblings aged 7–15 years, mother’s labor force participation, and whether the household is extended or nuclear to elucidate the potential negative effects of father absence that might be offset by these variables. Other child-level controls include sex and age, and the mother-level controls include Spanish-speaking ability (if she is indigenous), years of schooling, and age. Spanish speaking is determined by the language spoken at home, designed to capture a high degree of assimilation into the Ladino culture, and expected to increase school enrollment. Community-level variables are the proportion of residents in the non-agricultural sector, the proportion of indigenous people, and the proportion of mothers who completed elementary school. The last three variables are constructed based on the aggregation of the same data at the cluster level. Residence in a community with a higher proportion of residents in the non-agricultural sector is designed to capture a high level of modernization and expected to decrease the need for children’s labor contribution while increasing the demand for their better education. A larger proportion of indigenous residents might facilitate indigenous children’s enrollment because their numerical dominance in the community may counteract their “inferior” ethnic status, which might otherwise discourage them from attending school. Finally, well-educated neighbors might serve as role models for socioeconomic success, encouraging even less-educated mothers to enroll their children, regardless of ethnicity.

Results

Father Absence: Separate Living Arrangements and Lack of Paternity Establishment and Child Support Payments

First, the prevalence of father absence in children’s lives is documented through a series of cross-tabulations. The first indicator of fathers’ lack of involvement in children’s lives is their separate living arrangements from their children. Table 1 shows the proportion of children who reside with their fathers according to age and ethnicity. As expected, indigenous childrenFootnote 6 are more likely to live with their biological fathers than their Ladino counterparts in every age group. The average proportion of indigenous children with co-resident fathers is 92% while it is 85% in the Ladino sample, and this difference is statistically significant. The proportions of children with fathers in their households decrease over ages for both the ethnic groups, probably mainly because of the union dissolution of their parents. However, the association between age and co-resident status is statistically significant only for Ladino children, which is probably because of higher union instability among Ladina mothers.

Subsequently, I look at ethnic differences in nonresident fathers’ paternity establishment and monetary child support. Paternity establishment, apart from being crucial for mothers to legally claim child support payments from the fathers of their children (Argys and Peters 2001), has symbolic, social importance in Latin America (Budowski and Bixby 2003). While children legally recognized by their fathers are entitled to have their fathers’ surnames in addition to their mothers’, children without established paternity are left with only one surname given by their mothers, and thus are forced to carry a visible stigma of being fatherless (Werthemer 2006). Economic supportFootnote 7 is important because it alleviates poverty (Amato and Gilbreth 1999; Argys et al. 2001; Bartfeld 2000), which is one of the most important disadvantages suffered by lone mothers and their children.

Paternity establishment is determined whether “the (biological) father put his surname at the birth registration (al momento de inscriber a [name of the child] en el registro civil el padre de [name of the child] le puso su apellido),” or agreed to be recorded as the father, and child support is defined by the receipt of cash of any amount at the time of the survey. According to the first row of Table 2, 64% of all children who live away from their fathers, regardless of ethnicity, were legally recognized by them, and there is no significant difference by ethnicity. The same table indicates that indigenous children are less likely to be economically supported by their nonresident fathers than their Ladino counterparts (14 vs. 30%). Here, the ethnic difference is statistically significant. For the vast majority of the cases where paternity was established (93% for indigenous children and 97% for Ladino children), paternity acknowledgement was done voluntarily by the biological fathers. The paternity of the remaining children (7% for indigenous and 3% for Ladino) was established by court orders or through compulsion by the families of the mothers. These ethnic differences are marginally significant (p < .10). For the cases where children’s paternity was not established, 70% of the fathers of both the ethnic groups combined (there are no significant ethnic differences) “did not want to legally recognize the children” while for 19% of the cases, the “mothers did not want the fathers to legally recognize their children.”

The last two rows of Table 2 demonstrate the associations between paternity establishment and child support payments. For indigenous children, paternity establishment does not seem to have a major role in economic support payments: the proportion of the children who receive economic support is 11% when paternity was established and 16% otherwise. These figures are not significantly different. On the other hand, the proportion of Ladino children who are economically supported increases from 5% without established paternity to 44% with established paternity. The difference in these figures in the Ladino sample is statistically significant.

School Enrollment Status

I begin the second section by exploring the observed patterns of school enrollment and other potential socioeconomic determinants of school enrollment by the fathers’ co-resident status with their children and ethnicity as shown in Table 3. I find an initial support for the negative association between the school enrollment status and father absence among indigenous children: A significantly smaller proportion of indigenous children living away from their fathers are enrolled in school as compared to their counterparts living in two-biological-parent families. However, the father’s co-resident status does not seem to have a significant impact on Ladino children’s school enrollment.

There are several significant differences in other variables with respect to fathers’ co-resident status within each ethnic group. As suggested by the Latin American literature, children who live away from their biological fathers have fewer siblings, their mothers are more likely to be in the labor force, and their households are more likely to be extended rather than nuclear, regardless of ethnicity, all of which might counteract the potential disadvantage suffered by children without fathers. Additionally, fatherless Ladino children are more likely to live in a modernized community. Both indigenous and Ladino children in father-absent households are more likely to be found in a community with a higher proportion of women who have graduated from primary school than their respective counterparts in two-parent households.

The first multivariate model examines whether the absence of the biological father in the household has a negative effect on children’s school enrollment status, without controlling for the household economic status or child support payments. The results are presented in the first column of Table 4 for the indigenous sample, and the fourth column for the Ladino sample. Holding constant several child, mother, and community characteristics, father absence in the household significantly decreases the indigenous children’s likelihood of enrollment in school. A small and non-significant interactive effect between the child’s sex and father absence in the indigenous sample suggests that living away from fathers has similarly adverse effects on girls and boys. Father absence also negatively affects the school enrollment for Ladinos, but only for the male children as expected. The positive and significant coefficient of the interaction between father absence and the child’s female sex is nearly as large as the coefficient of father absence that pertains to boys. This indicates that the effect of father absence on Ladina girls is close to zero. Father absence in the household seems to be only slightly more deleterious for indigenous children than for Ladino male children: the Y-standardized coefficient of father absence for both the indigenous girls and boys is −0.573 (odds ratio, or OR: 0.564) while it is −0.530 (OR: 0.589) for Ladino male children.

Subsequently, I assess the degree to which this negative effect of father absence can be explained by the decreased economic resources in the household. In this second and subsequent models, the interaction between father absence and the child’s sex is maintained in the Ladino sample, though omitted in the indigenous sample for parsimony. Hence, the analysis focuses on the effects of father absence among the indigenous children of both the sexes and Ladino male children. The coefficients of the household economic status are, not surprisingly, extremely large and significant in both the samples, suggesting that it is one of the key determinants of children’s school enrollment, regardless of ethnicity. The introduction of this variable decreases the coefficient of father absence in both the ethnic groups; however, it is less substantial for indigenous children as hypothesized. The reduction in the indigenous sample is approximately 9% from a coefficient of −0.573 to −0.520 (OR: 0.595) whereas it decreases by 38% from −0.530 to −0.331 (OR: 0.718) in the Ladino sample. This suggests that a relatively smaller fraction of the negative effect of father absence in indigenous households operates by reducing economic resources. This is consistent with the argument that fathers of indigenous children play a more important social, rather than economic, role while the role of Ladino children’s fathers is more strongly related to economic factors.

Father absence in both indigenous and Ladino households continues to have significantly negative effects even after the household economic status is held constant in the second model. Finally, whether the receipt of child support payments from nonresident fathers attenuates this negative effect is examined. Regardless of ethnicity, children who do not live with their fathers but receive child support payments are not significantly less likely to be enrolled in school than their counterparts in two-parent households. On the other hand, their counterparts without child support payments are significantly disadvantaged in school enrollment. However, child support payments seem to have weaker effects on indigenous children: the coefficient for the indigenous children with economic support is still negative and large while it is no longer negative for their Ladino male counterparts.

The main results of other variables are briefly discussed based on this third and final model. Female children are significantly less likely to be enrolled in school for both the ethnic groups; however, consistent with the pattern shown in Fig. 1, such a negative effect of being a girl is stronger in the indigenous sample. For indigenous children, the number of school-age brothers and sisters does not have any effects on their school enrollment whereas its large and significantly negative effect in the Ladino sample indicates that Ladino siblings may compete for parental resources. The effect of indigenous mothers’ Spanish-speaking ability is positive as expected, but not significant. Mothers’ education significantly increases school enrollment at a similar rate for indigenous and Ladino children. Older mothers are significantly more likely to have their children in school than younger mothers, but this is only true in the Ladino sample. Mothers’ labor force participation has a positive effect for both the ethnic groups; however, such an effect is significant only in the indigenous sample. The presence of grandparents in the house hold has no significant effect for both the ethnic groups. The proportion in the non-agricultural sector in a community unexpectedly and significantly decreases Ladino children’s school enrollment. The proportion of indigenous residents has a larger positive effect in the indigenous sample as expected; however, such an effect is not statistically significant. Finally, a higher level of educational attainment at the community level has an additional and strong positive effect on school enrollment among indigenous children.

Discussion and Conclusions

The study shows that a non-negligible proportion of children (13% of the children aged 0–15 years of both the ethnic groups combined) live away from their biological fathers in Guatemala. Slightly over one-third of these children are not legally recognized by their fathers, and three-quarters do not receive child support payments, suggesting that nonresident fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives might be limited. This study also highlights the important ethnic differences in the prevalence and consequences of father absence. Bivariate analyses show that indigenous children are more likely to share the same household with their biological fathers as expected; however, in the fewer cases where indigenous children live away from their fathers, these fathers are less likely to provide child support payments than the fathers of Ladino children, appearing to be less committed to the children’s welfare. However, the non-significant difference in paternity establishment between indigenous and Ladino children and the similarly non-significant association between paternity establishment and child support payments among indigenous children suggest that the absent fathers of indigenous children are likely to be also indigenous, and thus may be poor and unable to provide economic support, rather than lacking concern for their children.

Multivariate analyses establish that father absence in the household significantly hampers children’s likelihood of school enrollment for both the ethnic groups, except for Ladina female children. Consistent with the hypothesis, a smaller proportion of the negative effect of living away from fathers is attributed to increased poverty in fatherless households for indigenous children than for Ladino male children, and father absence is more deleterious for indigenous children than for Ladino boys when the household economic status is controlled. To the extent that fathers belong to the same ethnic group as their children, the findings suggest that the role of indigenous fathers extends beyond the economic role as seen for Ladino fathers.

A potential scenario behind this ethnic difference may lie in the greater gender difference in public appearance between indigenous partners than that between Ladino partners. Although Guatemalan patriarchy prescribes that men are public figures and women belong to the domestic sphere, regardless of ethnicity, the appearance of indigenous women in public is substantially more restricted than that of Ladina women. Indigenous women are expected to protect the Mayan ethnic identity and avoid contact with Ladinos (Smith 1995). Monolingualism of Mayan language and the use of community-specific dress are far more common among indigenous women than among men and clearly demarcate the ethnic boundary. They not only help indigenous women distance themselves from Ladinos, but also inevitably result in their lack of connection with public institutions because “public” is exclusively a Ladino attribute, their personnel are predominantly Ladinos, and the language spoken in these institutions is Spanish. On the other hand, many indigenous men speak Spanish, wear Western clothing, and are literate (Pebley et al. 2005), which not only reflects substantially decreased barriers to Ladino culture but also suggests that they may be better skilled at making inquiries and preparing the paperwork necessary to register their children in school. In other words, indigenous fathers serve as a critical connection between children and the world outside of the household; therefore, father absence in the indigenous household may signify a loss of a primary contact with schools, leading to the lower likelihood of indigenous children’s school enrollment.

On the other hand, Ladina single mothers are likely to face far fewer obstacles approaching schools for their children’s enrollment than their indigenous counterparts because they belong to the dominant ethnic group. Many Ladina mothers are the primary contact persons with school officials even when their male partners are present in their households. According to the auxiliary analysis, inquiries and the paperwork for children’s school registration in two-parent households are done by the mothers alone for 52% of Ladino children, by the fathers alone for 32%, and by both for 16% while the corresponding figures for indigenous children are 32, 53, and 13%, respectively, confirming such an ethnic difference. Therefore, if not constrained by an economic hardship, Ladina mothers are more likely to be competent in facilitating their children’s school enrollment alone than their indigenous counterparts.

Another important finding is that Ladina female children who do not reside with their biological fathers are by no means less likely to be enrolled in school than their counterparts in two-parent households. The significant interaction between child’s sex and father absence in the household, observed even before the household economic status is controlled for, suggests that an economic disadvantage does not discourage Ladina single mothers from enrolling their daughters in school. There are two indications. First, the greater distance between fathers and daughters in the Ladino household suggested in the literature may indeed diminish the socio-emotional importance of the presence of fathers for their female children. Second, Ladina mothers may favor daughters in the allocation of economic resources in the household, similarly to the evidence found elsewhere for parents’ preference for same-sex children (Thomas 1994).

Regardless of ethnicity, children in father-absent households who receive economic support from their nonresident fathers are not significantly less likely to be enrolled in school when compared with their counterparts in two-parent households. The larger reduction of the negative effect of father absence by child support payments for Ladino boys seems consistent with the argument that the Ladino fathers have a more important economic, rather than social, role. However, it is important to note that child support payments by nonresident fathers may be associated with the quality of their relationships with their children (Nepomnyaschy 2007; Seltzer et al. 1989) and these fathers may also play supervisory and authoritative roles.

A potential factor that determines the quality of relationships between nonresident fathers and their children is the family structure history, such as whether they were born to single mothers or once-wedded parents and, in the case of the latter, the length of unions before dissolution or parental death (Sweeney 2007). A father who has been in a union with the mother of his children, especially for a longer period of time, is likely to have a stronger attachment to the children, thus maintaining closer ties with them even after the partnership with their mother has ended (Buvinic et al. 1992). Moreover, the duration of separation might also be a key determinant of a nonresident father’s involvement with his children (Carson 2008; Seltzer 1991). On the other hand, a father who has never been in a union with the mother is least likely to have any bond with his children; therefore, the consequences of father absence in the household for these children might be the severest. However, stress associated with family structure transitions and parental death might have strong, albeit temporal, adverse effects on children’s well-being (Brown 2006; Charles et al. 2002; McLanahan 1985; Sanz-de-Galdeano and Vuri 2007). Additional work needs to assess the nature and characteristics of the relationships between nonresident fathers and their children (Carson 2006; King and Sobolewski 2006), particularly addressing the potential diversity in family structures, to better identify the mechanisms by which child support payments improve the chances of school enrollment among children in father-absent households. It also needs to investigate the extent to which ethnic differences in the consequences of father absence in households are explained by those in the patterns of family structure history.

Unlike the literature in the U.S. that consistently suggests that the racial and ethnic differences in the family structure reinforce existing racial and ethnic stratification, results of this study reveal a more complex picture, showing diverse associations between ethnicity and three indicators of fathers’ involvement in their children’s lives and the differential effects of separate living arrangements from fathers on school enrollment, according to ethnicity. The lower likelihood of indigenous children living away from their fathers suggests that ethnic differences in the family structure in Guatemala are likely to alleviate than aggravate existing ethnic inequality. However, the results also demonstrate that apart from their generally lower likelihood of school enrollment as compared to Ladinos, indigenous children living away from their fathers, irrespective of sex, are more disadvantaged than fatherless Ladino children, particularly Ladina girls, when the household economic status is held constant. Furthermore, Ladino children are significantly more likely to receive economic support from their nonresident fathers than indigenous children, such support eliminates the disadvantages of Ladino male children, and they are as likely to be enrolled in school as their counterparts in two-parent households. Finally, the gender gap in school enrollment among indigenous children is greater than that among Ladinos, making indigenous girls in father-absent households the most vulnerable group of all.

The negative impact of father absence in children’s households on school enrollment established in this study provides evidence against the recent assertion that female household headship is not responsible for the intergenerational transmission of disadvantage for indigenous children in Guatemala. Further work is needed to assess other social, behavioral, and psychological measures of children’s well-being to ensure a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between ethnicity and father absence.

Notes

Although the men’s sample contains the same information on the children except for their school enrollment status, it is not used in the present study because of its smaller size and the underreporting of children who do not reside with them.

Eight percent of the children (1,627) are excluded because their fathers lived away from their mothers at the time of the survey although the mothers reported being in unions while 3% of the children (556) are excluded because they lived away from their mothers.

As the normative age to begin primary education is 7 years in Guatemala, children who were at least 7 years old when the school year started on January 2002 were considered for this study.

Since the children’s sample is constructed based on the sample whose sampling units were mothers, children whose mothers were over 49 years old are not represented. This results in some bias in the distribution of mother’s age particularly among older children.

The results are potentially sensitive to the specification of household economic status. School enrollment might be more responsive to a short-term income fluctuation than to an accumulation of wealth that this proxy is meant to capture.

Children whose fathers are Ladinos are most likely to be considered as “Ladinos” even when their mothers are indigenous. This is because Ladinos are, by definition, mixed-race individuals. However, since the ethnicity of the fathers is not identified in the data, I refer to children of indigenous mothers as “indigenous children” and to children of Ladina mothers as “Ladino children” for the sake of convenience.

Neglect of child support payments is considered a crime, and family members who fail to support their dependents can be sent to prison for up to 2 years, according to the nation’s criminal law. Child support eligibility does not include the “legitimacy” of the children; therefore, children of a mother who has never legally married to the father can equally claim child support payments (Werthemer 2006).

References

Ali, M. M., Cleland, J., & Shah, I. H. (2003). Trends in reproductive behavior among young single women in Colombia and Peru: 1985–1999. Demography, 40(4), 659–673. doi:10.1353/dem.2003.0031.

Amato, P. R., & Gilbreth, J. G. (1999). Nonresident fathers and children’s well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61(3), 557–573. doi:10.2307/353560.

Argys, L. M., & Peters, H. E. (2001). Interactions between unmarried fathers and their children: The role of paternity establishment and child-support policies. The American Economic Review, 91(2), 125–129.

Argys, L. M., Peters, H. E., & Waldman, D. M. (2001). Can the Family Support Act put some life back into deadbeat dads? An analysis of child-support guidelines, award rates, and levels. The Journal of Human Resources, 36(2), 226–252. doi:10.2307/3069658.

Arias, E., & De Vos, S. (1996). Using housing items to indicate socioeconomic status: Latin America. Social Indicators Research, 38(1), 53–80. doi:10.1007/BF00293786.

Arriagada, I. (2002). Changes and inequality in Latin American families. CEPAL Review, 77, 135–153.

Ashenfelter, O., & Krueger, A. (1994). Estimates of the economic return to schooling from a new sample of twins. The American Economic Review, 84(5), 1157–1173.

Barker, G. (2003). Men’s participation as fathers in the Latin American and Caribbean region: A critical literature review with policy considerations. Unpublished manuscript. Washington, DC.

Bartfeld, J. (2000). Child support and the postdivorce economic well-being of mothers, fathers, and children. Demography, 37(2), 203–213. doi:10.2307/2648122.

Bastos, S. (1997). Desbordando Patrones: El Comportamiento Doméstico de los Hombres. La Ventana, 6, 164–222.

Bastos, S. (1999). Concepciones del hogar y ejercicio del poder. El caso de los mayas de ciudad de Guatemala. In M. González de la Rocha (Ed.), Divergencias del modelo tradicional: Hogares de jefatura femenina en América Latina (pp. 37–75). México DF: CIESAS.

Bossen, L. (1984). The redivision of labor: Women and economic choice in four Guatemalan communities. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Bronstein, P. (1984). Differences in mothers and fathers behaviors toward children: A cross-cultural-comparison. Developmental Psychology, 20(6), 995–1003. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.20.6.995.

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Markman, L. B. (2005). The contribution of parenting to ethnic and racial gaps in school readiness. The Future of Children, 15(1), 139–168. doi:10.1353/foc.2005.0001.

Brown, S. L. (2006). Family structure transitions and adolescent well-being. Demography, 43(3), 447–461. doi:10.1353/dem.2006.0021.

Budowski, M., & Bixby, L. R. (2003). Fatherless Costa Rica: Child acknowledgment and support among lone mothers. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 34(2), 229–254.

Buvinic, M., & Gupta, G. R. (1997). Female-headed households and female-maintained families: Are they worth targeting to reduce poverty in developing countries? Economic Development and Cultural Change, 45(2), 259–280. doi:10.1086/452273.

Buvinic, M., Valenzuela, J. P., Molina, T., & Gonzalez, E. (1992). The fortunes of adolescent mothers and their children—the transmission of poverty in Santiago, Chile. Population and Development Review, 18(2), 269–297. doi:10.2307/1973680.

Cabrera Pérez-Armiñán, M. L. (1992). Tradición y cambio de la Mujer K’iche’. Guatemala: IDESAC.

Carson, M. (2006). Family structure, father involvement, and adolescent behavioral outcomes. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 68, 137–154. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00239.x.

Carson, M. (2008). Coparenting and nonresident fathers’ involvement with young children after a nonmarital birth. Demography, 45(2), 461–488. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0007.

Casaus Arzu, M. E. (1999). La Metamorfosis del Racismo en la Elite de Poder en Guatemala. In A. Bianch, C. R. Hale, & P. Murga (Eds.), ¿Racismo en Guatemala? (pp. 47–92). Guatemala: AVANSCO.

CEPAL. (1995). Familia y futuro. Un programa regional en América Latina y el Caribe (Vol. 37). Santiago, Chile: ENLAC.

CEPAL. (2001). Panorama social de América Latina. Santiago, Chile: CEPAL.

Chant, S. (1997). Women-headed households: Poorest of the poor? Perspectives from Mexico, Costa Rica and the Philippines. IDS Bulletin, 28(3), 26–48.

Chant, S. (2003). Female household headship and the feminization of poverty: Facts, fictions and forward strategies. Unpublished manuscript, Working paper. London: Gender Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Charles, R., Martinez, J., & Forgatch, M. S. (2002). Adjusting to change: Linking family structure transitions with parenting and boy’s adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 16(2), 107–117. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.16.2.107.

de Keijzer, B. (1998). Paternidad y transición de género. In B. Schmuckler (Ed.), Cambios transcendentales en América Latina y el Caribe. Mexico city: EDAMEX, Population Council.

Desai, S. (1992). Children at risk: The role of family structure in Latin America and west Africa. Population and Development Review, 18(4), 689–717. doi:10.2307/1973760.

De Vos, S. (1998). Nuptiality in Latin America: The view of a sociologist and family demographer. Unpublished manuscript, Working paper. Wisconsin: Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

De Vos, S., & Arias, E. (1998). Female headship, marital status and material well-being—Colombia 1985. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 39(2), 177–197. doi:10.1177/002071529803900202.

Engle, P. L. (1995). Father’s money, mother’s money, and parental commitment: Guatemala and Nicaragua. In R. L. Blumberg, C. Rakowsi, I. Tinker, & M. Monteón (Eds.), Engendering wealth and well-being: Empowerment for global change (pp. 155–179). Boulder, CO: Westview.

Engle, P. L., & Breaux, C. (1998). Fathers’ involvement with children: Perspectives from developing countries. Social Policy Report, XII(1), 2–21.

Feijoó, M. d. C. (1999). De pobres mujeres a mujeres pobres. In M. González de la Rocha (Ed.), Divergencias del modelo tradicional: Hogares de fejatura femenina en América Latina (pp. 155–162). México DF: CIESAS.

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. H. (2001). Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data-or tears: An application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography, 38(1), 115–132.

Fonseca, J. C. L. (1998). Paternidade adolescente: Da investigaçao á intervençao. In M. Arilha, S. Unbehaum, & B. Medrado (Eds.), Homens e masculinidades. Outras Palavras (pp. 185–214). São Paulo, Brazil: Ecos/Editora 23.

Fuller, N. (2000). Work and masculinity among Peruvian urban men. European Journal of Development Research, 12(2), 93–114. doi:10.1080/09578810008426767.

Fuwa, N. (2000). The poverty and heterogeneity among female-headed households revisited: The case of Panama. World Development, 28(8), 1515–1542. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00036-X.

Glitenberg, J. (1994). To the mountain and back: The mysteries of Guatemalan highland family.

González de la Rocha, M. (1999a). Hogares de jefatura femenina en México: Patrones y formas de vida. In M. González de la Rocha (Ed.), Divergencias del modelo tradicional: Hogares de jefatura femenina en América Latina (pp. 125–154). México DF: CIESAS.

González de la Rocha, M. (1999b). A manera de introducción: Cambio social, transformación de la familia y divergencias del modelo tradicional. In M. González de la Rocha (Ed.), Divergencias del modelo tradicional: Hogares de jefatura femenina en América Latina (pp. 19–36). México DF: CIESAS.

Gutmann, M. C. (1996). The meanings of macho: Being a man in Mexico city. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gutmann, M. C. (2005). Mexican men who abandon their families: Households as border zones in Mexico city. Estudios Interdisciplinarios de America Latina y el Caribe, 16(1).

Hall, G., & Patrinos, H. A. (Eds.). (2006). Indigenous peoples, poverty and human development in Latin America 1994–2004. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hallman, K., Paracca, S., Catino, J., & Ruiz, M. J.(2005). Multiple disadvantages of Mayan females: The effects of gender, ethnicity, poverty, and residence on education in Guatemala. Unpublished manuscript, Working paper. Washington, DC: Population Councils.

Henao, H. (1994). El hombre finisecular en busca de identidad: Reflexiones a partir del caso antioqueño. Unpublished manuscript. Paper presented at the symposium Sexualidad y Construcción de Identidad de Género, VII Congreso de Antropología. Madellín, Columbia: Universidad de Antioquia.

Hofferth, S. L. (2003). Race/ethnic differences in father involvement in two-parent families: Culture, context, or economy? Journal of Family Issues, 24(2), 185–216. doi:10.1177/0192513X02250087.

Kaztman, R. (1992). ¿Por qué los hombres son tan irreponsables? Revista de la CEPAL, 46.

Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. (2007). Cohabitations and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Unpublished manuscript, Presented at the Annual Meetings of the Population Association of America, New York.

King, V., & Sobolewski, J. M. (2006). Nonresident fathers’ contributions to adolescent well-being. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 68(3), 537–557. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00274.x.

King, V., Harris, K. M., & Heard, H. E. (2004). Racial and ethnic diversity in nonresident father involvement. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66(1), 1–21. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00001.x.

Lindstrom, D. P. (2003). Rural–urban migration and reproductive behavior in Guatemala. Population Research and Policy Review, 22(4), 351–372. doi:10.1023/A:1027336615298.

Lloyd, C. B., & Mensch, B. S. (2008). Marriage and childbirth as factors in dropping out from school: An Analysis of DHS data from sub-Saharan Africa. Population Studies, 62(1), 1–13. doi:10.1080/00324720701810840.

Lundberg, S., McLanahan, S., & Rose, E. (2007). Child gender and father involvement in fragile families. Demography, 44(1), 79–92. doi:10.1353/dem.2007.0007.

Marcoux, A. (1998). The feminization of poverty: Claims, facts, and data needs. Population and Development Review, 24(1), 131–139. doi:10.2307/2808125.

Mare, R. D. (2006). Response: Statistical models of educational stratification—Hauser and Andrew’s models for school transitions. Sociological Methodology, 36, 27–37. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9531.2006.00173.x.

Maynard, E. (1974). Guatemalan women: Life under two type of patriarchy. In C. Matthiasson (Ed.), Many sisters (pp. 77–98). New York: The Free Press.

McLanahan, S. (1985). Family structure and the reproduction of poverty. American Journal of Sociology, 90(4), 873–901. doi:10.1086/228148.

McLanahan, S., & Percheski, C. (2008). Family structure and reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134549.

MSPAS. (2003). Guatemala: Encuesta Nacional de Salud Materno Infantil 2002. Guatemala: Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social, MSPAS.

Nelson, D. M. (1998). Perpetual creation and decomposition: Bodies, gender, and desire in the assumptions of a Guatemalan discourse of Mestizaje. Journal of Latin American Anthropology, 4(1), 74–111. doi:10.1525/jlat.1998.4.1.74.

Nepomnyaschy, L. (2007). Child support and father-child contact: Testing reciprocal pathways. Demography, 44(1), 93–112. doi:10.1353/dem.2007.0008.

Parke, R. D., & Buriel, R. (1998). Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In W. Damon & N. Eisenburg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 463–552). New York: Wiley.

Paul, L. (1974). The mastery of work and the mystery of sex. In M. Z. Rosaldo (Ed.), Women, culture and society. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Pebley, A. R., Goldman, N., & Robles, A. (2005). Isolation, integration, and ethnic boundaries in rural Guatemala. The Sociological Quarterly, 46, 213–236. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2005.00010.x.

Quisumbing, A. R., Haddad, L., & Peña, C. (2001). Are women overrepresented among the poor? An analysis of poverty in 10 developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 66(1), 225–269. doi:10.1016/S0304-3878(01)00152-3.

Safa, H. I. (1999). Women coping with crisis: Social consequences of export-led industrialization in the Dominican Republic. North-South Agenda Paper No. 36. Miami: North-South Center, University of Miami.

Sanz-de-Galdeano, A., & Vuri, D. (2007). Parental divorce and students’ performance: Evidence from longitudinal data. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 69(3), 321–338. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0084.2006.00199.x.

Schwartz, S. J., & Finley, G. E. (2005). Fathering in intact and divorced families: Ethnic differences in retrospective reports. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 67(1), 207–215. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00015.x.

Seltzer, J. A. (1991). Relationships between fathers and children who live apart: The father’s role after separation. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 79–101. doi:10.2307/353135.

Seltzer, J. A., Schaeffer, N. C., & Charng, H. W. (1989). Family ties after divorce: The relationship between visiting and paying child-support. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51(4), 1013–1031. doi:10.2307/353213.

Sigle-Rushton, W., & McLanahan, S. (2004). Father absence and child well-being: A critical review. In The future of the family (pp. 116–155). New York: Russel Sage.

Smith, C. A. (1995). Race-class-gender ideology in Guatemala: Modern and anti-modern forms. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 37(4), 723–749.

Sweeney, M. M. (2007). Stepfather families and the emotional well-being of adolescents. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(March), 33–49.

Thomas, D. (1994). Like father, like son—like mother, like daughter—parental resources and child height. The Journal of Human Resources, 29(4), 950–988. doi:10.2307/146131.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2008). Data centre. http://stats.uis.unesco.org/unesco/TableViewer/document.aspx?ReportId=143&IF_Language=eng. Retrieved 7 Mar 2008.

Varley, A. (2001). Gender, families and households. In V. Desai & R. Potter (Eds.), The companion to development studies (pp. 219–234). London: Edward Arnold.

Viveros Vigoya, M. (2001). Contemporary Latin American perspectives on masculinity. Men and Masculinities, 3(3), 237–260. doi:10.1177/1097184X01003003002.

Waternberg, L. (1999). Vulnerabilidad y jefatura en los hogares urbanos colombianos. In M. González de la Rocha (Ed.), Divergencias del modelo tradicional: Hogares de jefatura femenina en América Latina (pp. 77–96). México DF: CIESAS.

Werthemer, J. W. (2006). Gloria’s story: Adulterous concubinage and the law in twentieth-century Guatemala. Law and History Review, 24(2), 375–422.

Wooldridge, J. (2009). Introductory economics: A modern approach (4th ed.). Mason, OH: Wouth-Western College Publishing.

Yoshioka, H. (2006). A Q-analysis of census data: Intra-household income allocation and school attendance in Chiapas, Mexico. Quality and Quantity, 40, 1061–1077. doi:10.1007/s11135-005-5080-8.

Acknowledgments

A version of this study was presented at the 2008 meetings of the Population Association of America, New Orleans. This research was partially supported by a Mellon Fellowship in Latin American Sociology. I thank Donald Treiman, Edward Telles, Megan Sweeney, Steven Wallace, Paul Stupp, Timothy Johnson, Reina Turcios-Ruiz, and Edgar Sajquim for their valuable input on this article.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishida, K. The Role of Ethnicity in Father Absence and Children’s School Enrollment in Guatemala. Popul Res Policy Rev 29, 569–591 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-009-9160-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-009-9160-7