Abstract

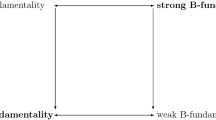

On the truthmaker view of ontological commitment [Heil (From an ontological point of view, 2003); Armstrong (Truth and truthmakers, 2004); Cameron (Philosophical Studies, 2008)], a theory is committed to the entities needed in the world for the theory to be made true. I argue that this view puts truthmaking to the wrong task. None of the leading accounts of truthmaking—via necessitation, supervenience, or grounding—can provide a viable measure of ontological commitment. But the grounding account does provide a needed constraint on what is fundamental. So I conclude that truthmaker commitments are not a rival to quantifier commitments, but a needed complement. The quantifier commitments are what a theory says exists, while the truthmaker commitments are what a theory says is fundamental.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Convention for variables: Here and in what follows, “p” is dedicated to propositions, and “w” (as well as its subscripted counterparts “w 1” and “w 2”) to worlds.

Those sceptical of unrestricted composition may replace ‘(∃x)’ with the plural quantifier ‘(∃xx)’ and speak plurally of ‘the truthmakers,’ as the entities whose joint existence necessitates the truth of the proposition in question. Those sceptical of transworld identity may replace ‘if x exists at w 2’ with ‘if x has a counterpart at w 2’ or (better) ‘if x has a duplicate at w 2.’ Nothing in what follows will turn on these details.

Among the many problems with MNec is the problem that the mind-making physical entity(s) could exist in a dualistic world, where the dualistic addition makes different mental entities exist (c.f. Hawthorne 2002; Leuenberger forthcoming). For instance, let my brain-state b ground my pain-state m. Still it is possible that b exist in a dualistic world w where my spirit state s changes things so that b and s together do not yield pain-state m. In w, b exists but m does not.

Indeed Armstrong’s totality fact, insofar as it conjoins all the first-order facts and then says that there are no more, further offends against the intuitions that the fundamental entities ought to be amenable to free recombination, and ought to be non-redundant. As to free recombination, none of the first-order facts can be altered without altering the totality fact, and the totality fact cannot be altered without altering at least some of the first-order facts. As to non-redundancy, the totality fact entails all the first-order facts. Indeed, once one posits the fundamental totality fact, it is mysterious why one would bother to posit any fundamental first-order facts whatsoever, since all of these are already entailed. The totality fact can go it alone.

Another way to get objects to serve is to modify TNec from ‘if x exists at w 2’ to ‘if x has a duplicate at w 2.’ See Parsons 1999 for further discussion.

This is the principle that Smith (1999, Sect. 4) refers to as TN+: if x truth-necessitates p, the x + y truth-necessitates p.

I must confess that I do not fully understand what ‘subtraction’ comes to for states-of-affairs. These have both object and property constituents. Presumably minimality on the object constituent can be spelled out mereologically, in terms of not being to subtract any parts and still have a truthmaker for the proposition in question. But minimality on the property constituent is trickier. Presumably one should not be able to subtract any conjuncts. But what about determinate-determinable relations? Should we also think of the determinable as ‘subtracted’ with respect to specificity? Fortunately the argument to come will not turn on any of these questions.

It may be worth recalling that Lewis himself endorsed the quantifier view of commitment (c.f. Lewis 1999). TSup was simply not built for the task of measuring commitments. This is no objection to TSup per se, but only an objection to the attempt to put TSup to a further task it was never intended for.

See Schaffer (forthcoming) for further defense of TGro. See especially Sect. 4 for an explanation of how to handle negative existentials through the combination of TGro with a monistic view of what is fundamental.

References

Aristotle. (1984). Categories. In J. Barnes (Ed.), The complete works of Aristotle: The revised Oxford translation (Vol. 1, pp. 3–24). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Armstrong, D. M. (1997). A world of states of affairs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Armstrong, D. M. (2004). Truth and truthmakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bigelow, J. (1988). The reality of numbers: A physicalist’s philosophy of mathematics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bricker, P. (2006). The relation between general and particular: Entailment vs supervenience. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, 2, 251–287.

Cameron, R. (2008). Truthmakers and ontological commitment: Or how to deal with complex objects and mathematical ontology without getting into trouble. Philosophical Studies, 140, 1–18.

Cameron, R., & Barnes, E. (2007). A critical study of John Heil’s ‘From an ontological point of view’. SWIF Philosophy of Mind Review, 6, 22–30.

Hawthorne, J. (2002). Blocking definitions of materialism. Philosophical Studies, 110, 103–113.

Heil, J. (2003). From an ontological point of view. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kim, J. (1993). Postscripts on supervenience. In Supervenience and mind: Selected philosophical essays (pp. 161–174). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leibniz, G. W. F. (1960). Discourse on metaphysics. In The Rationalists (pp. 409–453). New York: Anchor Books.

Leuenberger, S. (forthcoming). Ceteris Absentibus Physicalism. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, 4.

Lewis, D. (1999). Noneism or allism? In Papers in metaphysics and epistemology (pp. 152–163). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, D. (2001). Truthmaking and difference-making. Nous, 35, 602–615.

McLaughlin, B., & Bennett, K. (2005). Supervenience. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/stanford/entries/supervenience/. Accessed 21 April 2008.

Merricks, T. (2007). Truth and ontology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Parsons, J. (1999). There is no ‘Truthmaker’ argument against nominalism. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 77, 325–334.

Quine, W. V. O. (1963). On what there is. In from a logical point of view (pp. 1–19). New York: Harper & Row.

Schaffer, J. (forthcoming). The least discerning and most promiscuous truthmaker. Philosophical Quarterly.

Smith, B. (1999). Truthmaker realism. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 77, 274–291.

Van Inwagen, P. (1990). Material beings. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ross Cameron, Matti Eklund, and the audience at Ontological Commitment in Sydney.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schaffer, J. Truthmaker commitments. Philos Stud 141, 7–19 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-008-9260-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-008-9260-y