Abstract

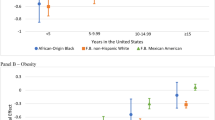

Although researchers have found an inverse relationship between length of U.S. residence and health, research on this issue among African-born immigrants is limited. Data from the 2011–2015 National Health Interview Surveys were pooled for African-born immigrants (N = 1137) and used to estimate weighted ordinary least squares regression models on self-reported health, adjusting for common immigrant health predictors. Length of U.S. residence was associated with significant health status declines only among those that had lived in the U.S. for 10 to less than 15 years (b = − 0.235, p < 0.05), net of covariates. African-born immigrants may have both different selection processes than other immigrants and not follow common integration patterns. These findings suggest that existing immigrant health frameworks may need modification to fully apply to this growing U.S. immigrant population.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson M. African immigrant population in US steadily climbs. Pew Research Center. 2017. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/02/14/african-immigrant-population-in-u-s-steadily-climbs/. Accessed 18 Jan 2018.

Anderson M, Lopez G. Key facts about Black immigrants in the U.S. Pew Research Center. 2018. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/24/key-facts-about-black-immigrants-in-the-u-s/. Accessed 28 Jan 2018.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Yearbook of immigration statistics: 2016. 2017. https://www.dhs.gov/immigration-statistics/yearbook/2016. Accessed 16 Aug 2018.

Capps R, McCabe K, Fix M. Diverse streams: African migration to the United States. 2012. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/CBI-african-migration-united-states. Accessed 24 Aug 2018.

Zong J, Batalova J. Sub-saharan African immigrants in the United States. 2017. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/sub-saharan-african-immigrants-united-states. Accessed 24 Aug 2018.

McCabe K. African immigrants in the United States. 2011. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/african-immigrants-united-states. Accessed 23 Aug 2018.

Venters H, Gany F. African immigrant health. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;13(2):333–44.

Kamya HA. African immigrants in the United States: the challenge for research and practice. Soc Work. 1997;42(2):287–287.

Wallace S, Young MEDT, Rodríguez MA, Brindis CD. A social determinants framework identifying state-level immigrant policies and their influence on health. Popul Health. 2019;7:100316.

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS). 2018 ACS 1-year estimates, Table B05006. 2018. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=B05006&tid=ACSDT1Y2018.B05006. Accessed 1 June 2020.

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS). 2018 ACS 1-year estimates, Table S0504. 2018. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=s0504&tid=ACSST1Y2018.S0504. Accessed 1 June 2020.

Ruggles S, Flood S, Goeken R, Grover J, Meyer E, Pacas J, Sobek M. IPUMS USA: Version 10.0 . Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2020. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V10.0.

Elo IT, Frankenberg E, Gansey R, Thomas D. Africans in the American labor market. Demography. 2015;52(5):1513–42.

American Immigration Council. The diversity immigrant visa program: an overview. 2017. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/the_diversity_immigrant_visa_program_an_overview.pdf. Accessed 7 Sept 2018.

Morgan-Trostle J, Zheng K, Lipscombe C. The state of Black immigrants. 2018. https://www.stateofblackimmigrants.com. Accessed 24 Aug 2018.

U.S. Department of State. Summary of refugee admissions as of 31-July-2018. 2018. https://www.wrapsnet.org/admissions-and-arrivals/. Accessed 3 Sept 2018.

Thomas KJA, Logan I. African female immigration to the United States and its policy implications. Can J Afr Stud. 2012;46(1):87–107.

Itzigsohn J, Giorguli S, Vazquez O. Immigrant incorporation and racial identity: racial self-identification among Dominican immigrants. Ethn Racial Stud. 2005;28(1):50–78.

Singh GK, Liu L. Mortality trends, patterns, and differentials among immigrants in the United States: International Perspectives. In: Migration, health and survival. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham; 2017.

Singh GK, Rodriguez-Lainz A, Kogan MD. Immigrant health inequalities in the United States: use of eight major national data systems. Sci World J. 2013;2013:21.

Uretsky MC, Mathiesen SG. The effects of years lived in the United States on the general health status of California’s foreign-born populations. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9(2):125–36.

Acevedo-Garcia D, Bates LM. Latino health paradoxes: empirical evidence, explanations, future research, and implications. Latinas/Os in the United States: changing the face of America. 2008;101–113.

Horevitz E, Organista KC. The Mexican health paradox: expanding the explanatory power of the acculturation construct. Hispanic J Behav Sci. 2013;35(1):3–34.

Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the "salmon bias" and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1543–8.

Landale NS, Oropesa RS. Migration, social support and perinatal health: an origin-destination analysis of Puerto Rican women. J Health Soc Behav. 2001:166–183.

Scribner R, Dwyer JH. Acculturation and low birthweight among Latinos in the Hispanic HANES. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(9):1263–7.

Vega WA, Amaro H. Latino outlook: good health, uncertain prognosis. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15(1):39–67.

Hummer RA, Melvin JE, He M. Immigration: health and mortality. In: International encyclopedia of the Soc. & Beh. Sciences, 2n edn. Elsevier, New York; 2015:654–661.

Ro A. The longer you stay, the worse your health? A critical review of the negative acculturation theory among Asian immigrants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(8):8038–57.

Escobar JI, Vega WA. Mental health and immigration's AAAs: where are we and where do we go from here? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(11):736–40.

Hurh WM, Kim KC. Adaptation stages and mental health of Korean male immigrants in the United States. Int Migr Rev. 1990;24(3):456–79.

Frisbie WP, Cho Y, Hummer RA. Immigration and the health of Asian and Pacific Islander adults in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153(4):372–80.

Hamilton TG, Palermo T, Green TL. Health assimilation among Hispanic immigrants in the United States: the impact of ignoring arrival-cohort effects. J Health Soc Behav. 2015;56(4):460–77.

Acevedo-Garcia D, Bates LM, Osypuk TL, McArdle N. The effect of immigrant generation and duration on self-rated health among US adults 2003–2007. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(6):1161–72.

Kimbro RT, Gorman BK, Schachter A. Acculturation and self-rated health among Latino and Asian immigrants to the United States. Soc Probl. 2012;59(3):341–63.

Afable-Munsuz A, Ponce NA, Rodriguez M, Perez-Stable EJ. Immigrant generation and physical activity among Mexican, Chinese & Filipino adults in the U.S. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(12):1997–2005.

Ro A, Bostean G. Duration of US stay and body mass index among Latino and Asian immigrants: a test of theoretical pathways. Soc Sci Med. 2015;144:39–47.

John DA, De Castro A, Martin DP, Duran B, Takeuchi DT. Does an immigrant health paradox exist among Asian Americans? Associations of nativity and occupational class with self-rated health and mental disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2085–98.

Lee S, O'Neill A, Park J, Scully L, Shenassa E. Health insurance moderates the association between immigrant length of stay and health status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(2):345–9.

Gee GC, Ryan A, Laflamme DJ, Holt J. Self-reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 initiative: the added dimension of immigration. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1821–8.

Akresh IR, Do DP, Frank R. Segmented assimilation, neighborhood disadvantage, and Hispanic immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2016;149(1):114–21.

Hamilton TG. The healthy immigrant (migrant) effect: in search of a better native-born comparison group. Soc Sci Res. 2015;54:353–65.

Hamilton TG, Green TL. From the West Indies to Africa: a universal generational decline in health among Blacks in the United States. Soc Sci Res. 2018;73:163–74.

Hamilton TG, Hummer RA. Immigration and the health of US Black adults: does country of origin matter? Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(10):1551–600.

Read JG, Emerson MO. Racial context, Black immigration and the US Back/White health disparity. Soc Forces. 2005;84(1):181–99.

Reed HE, Andrzejewski CS, Luke N, Fuentes L. The health of African immigrants in the US: explaining the immigrant health advantage. The Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America. San Francisco, CA; 2012.

Okafor MTC, Carter-Pokras OD, Picot SJ, Zhan M. The relationship of language acculturation (English proficiency) to current self-rated health among African immigrant adults. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(3):499–509.

Alang SM, McCreedy EM, McAlpine DD. Race, ethnicity, and self-rated health among immigrants in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(4):565–72.

Reynolds MM, Chernenko A, Read JG. Region of origin diversity in immigrant health: moving beyond the Mexican case. Soc Sci Med. 2016;166:102–9.

Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38(1):21–37.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. General Health Status. 2018. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/General-Health-Status#one. Accessed 6 Feb 2018.

Parsons VL, Moriarity CL, Jonas K, Moore TF, Davis KE, Tompkins L. Design and estimation for the national health interview survey, 2006–2015. National Center for Health Statistics. 2014;2(165).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. About the national health interview survey. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm. Accessed 23 Aug 2018.

National Center for Health Statistics. Variance estimation guidance, NHIS 2006–2015 (adapted from the 2006–2015 NHIS survey description documents). 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/2006var.pdf. Accessed 22 Aug 2018.

Gubernskaya Z. Age at migration and self-rated health trajectories after age 50: understanding the older immigrant health paradox. J Gerontol B. 2014;70(2):279–90.

Antecol H, Bedard K. Unhealthy assimilation: why do immigrants converge to American health status levels? Demography. 2006;43(2):337–60.

Miranda PY, Yao NL, Snipes SA, BeLue R, Lengerich E, Hillemeier MM. Citizenship, length of stay, and screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer in women, 2000–2010. Cancer Cause Control. 2017;28(6):589–98.

Antecol H, Bedard K. Immigrants and immigrant health. In: Chiswick B, Miller P, editors. Handbook of the economics of international migration. Kidlington, Oxford: Elsevier; 2015. p. 271–314.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. 2017, StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX.

Feliciano C. Educational selectivity in US immigration: how do immigrants compare to those left behind? Demography. 2005;42(1):131–52.

Hamilton TG. Selection, language heritage, and the earnings trajectories of black immigrants in the United States. Demography. 2014;51(3):975–1002.

Andemariam EM. The challenges and opportunities faced by skilled African immigrants in the US job market: a personal perspective. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. 2007;5(1):111–6.

Cumoletti M, Batalova J. Middle Eastern and North African Immigrants in the United States. 2018. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/middle-eastern-and-north-african-immigrants-united-states. Accessed 24 Nov 2019.

Samari G. Islamophobia and public health in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):1920–5.

Jasso G, Douglas S. Massey, Mark R. Rosenzweig and James P. Smith. The New Immigrant Survey. 2005. https://nis.princeton.edu/index.html. Accessed 30 July 2019.

Okafor MTC, Carter-Pokras OD, Zhan M. Greater dietary acculturation (dietary change) is associated with poorer current self-rated health among African immigrant adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(4):226–35.

Ngoubene-Atioky AJ, Williamson-Taylor C. Culturally based health assumptions in Sub-Saharan African immigrants: body mass index predicting self-reported health status. J Health Psychol. 2019:1359105316683241.

Chaumba J. Health status, use of health care resources, and treatment strategies of Ethiopian and Nigerian immigrants in the United States. Soc Work Health Care. 2011;50(6):466–81.

Krause NM, Jay GM. What do global self-rated health items measure? Med Care 1994:930–42.

Alba RD, Logan JR, Stults BJ, Marzan G, Zhang W. Immigrant groups in the suburbs: a reexamination of suburbanization and spatial assimilation. Am Sociol Rev 1999:446–60.

Acknowledgements

Ezinne M. Nwankwo was supported by the UCLA Graduate Summer Research Mentorship program, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Health Policy Research Scholars program. Steven P. Wallace received support from NIMHD R01 MD012292 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through UCLA CTSI Grant UL1TR001881. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the NIH or any of the funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nwankwo, E.M., Wallace, S.P. Duration of United States Residence and Self-Reported Health Among African-Born Immigrant Adults. J Immigrant Minority Health 23, 773–783 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01073-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01073-8