Abstract

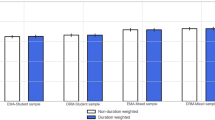

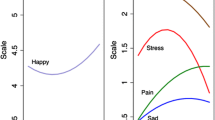

Duration-based measures of happiness from retrospectively constructed daily diaries are gaining in popularity in population-based studies of the hedonic experience. Yet experimental evidence suggests that perceptions of duration—how long an event lasts—are influenced by individuals’ emotional experiences during the event. An important remaining question is whether observational measures of duration outside the laboratory setting, where the events under study are engaged in voluntarily, may be similarly affected, and if so, for which emotions are duration biases a potential concern. This study assesses how duration and emotions co-vary using retrospective, 24-h diaries from a national sample of older couples. Data are from the Disability and Use of Time supplement to the nationally representative U.S. Panel Study of Income Dynamics. We find that experienced wellbeing (positive, negative emotion) and activity duration are inversely associated. Specific positive emotions (happy, calm) are not associated with duration, but all measures of negative wellbeing considered here (frustrated, worried, sad, tired, and pain) have positive correlations (ranging from 0.04 to 0.08; p < .05). However, only frustration remains correlated with duration after controlling for respondent, activity and day-related characteristics (0.06, p < .01). The correlation translates into a potentially upward biased estimate of duration of up to 10 min (20 %) for very frustrating activities. We conclude that estimates of time spent feeling happy yesterday generated from diary data are unlikely to be biased but more research is needed on the link between duration estimation and feelings of frustration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Both spouses had to be at least age 50 as of December 31, 2008 and at least one spouse age 60 or older at that time. Because the vast majority of married men and women ages 60 and older have spouses that are age 50 and older, the sample essentially represented married people ages 60 and older and their spouses.

<1 % of activities (N = 27) were omitted because the respondent was sleeping or did not report what they were doing.

References

Block, R. A. (1990). Models of psychological time. In R. A. Block (Ed.), Cognitive models of psychological time (pp. 1–35). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Block, R. A., George, E. J., & Reed, M. A. (1980). A watched pot sometimes boils: a study of duration experience. Acta Psychologica, 46(2), 81–94.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2011). American time use survey user’s guide: Understanding ATUS 2003–2009. http://www.bls.gov/tus/atususersguide.pdf. Accessed 9April, 2012.

Craik, F. I., & Hay, J. F. (1999). Aging and judgments of duration: effects of task complexity and method of estimation. Perception & Psychophysics, 61(3), 549–560.

Dockray, S., Grant, N., Stone, A. A., Kahneman, D., Wardle, J., & Steptoe, A. (2010). A comparison of affect ratings obtained with ecological momentary assessment and the Day Reconstruction Method. Social Indicators Research, 99(2), 269–283.

Droit-Volet, S., & Meck, W. H. (2007). How emotions colour our perception of time. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(12), 504–513.

Droit-Volet, S., et al. (2004). Perception of the duration of emotional events. Cognition and Emotion, 18, 849–858.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Kahneman, D. (1993). Duration neglect in retrospective evaluations of affective episodes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(1), 45–55.

Freedman, V. A., & Cornman, J. C. (2012). The Panel Study of Income Dynamics’ supplement on Disability and Use of Time (DUST) user guide: Release 2009.1. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Freedman, V. A., Stafford, F. P., Schwarz, N., Conrad, F. G., & Cornman, J. C. (2012). Disability, participation, and subjective wellbeing among older couples. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 588–596.

Gil, S., & Droit-Volet, S. (2008). Time perception, depression and sadness. Behavioural Processes, 80(2), 169–176. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2008.11.012.

Gould, W., Pitblado, J., & Poiv, B. (2010). Maximum likelihood estimation with Stata (4th ed.). Texas: Stata Press.

Hancock, P. A., & Rausch, R. (2010). The effects of sex, age, and interval duration on the perception of time. Acta Psychologica, 133(2), 170–179.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A., Schkade, D., Schwarz, M., & Stone, A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience. Science, 306, 1176–1780.

Kitamura, T., & Kumar, R. (1982). Time passes slowly for patients with depressive state. Acta Psychiatry Scandinavica, 65(6), 415–420.

Krueger, A. (2007). Are we having more fun yet? Categorizing and evaluating changes in time allocation. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2007(2), 193–215.

Krueger, A., & Stone, A. A. (2008). Assessment of pain: A community-based diary survey in the USA. Lancet, 371(9623), 1519–1525.

Kunzmann, U., Little, T. D., & Smith, J. (2000). Is age-related stability of subjective well-being a paradox? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the Berlin aging study. Psychology and Aging, 15, 511–526.

Liu, Y., & Wickens, C. D. (1994). Mental workload and cognitive task automaticity: An evaluation of subjective and time estimation metrics. Ergonomics, 37(11), 1843–1854.

Quigley, J. J., Combs, A. L., & O’Leary, N. (1984). Sensed duration of time: Influence of time as a barrier. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 58, 72–74.

Russell, J. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychological Review, 110(1), 145–172.

Schiffman, N., & Greist-Bousquet, S. (1992). The effect of task interruption and closure on perceived duration. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 30(1), 9–11.

Schwarz, N., Kahneman, D., & Xu, J. (2009). Global and episodic reports of hedonic experience. In R. Belli, D. Alwin, & F. Stafford (Eds.), Using calendar and diary methods in life events research (pp. 157–174). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Sévigny, M. C., Everett, J., & Grondin, S. (2003). Depression, attention, and time estimation. Brain and Cognition, 53(2), 351–353.

Stone, A. A., Schwartz, J. E., Schwarz, N., Schkade, D., Krueger, A., & Kahneman, D. (2006). A population approach to the study of emotion: Diurnal rhythms of a working day examined with the Day Reconstruction Method. Emotion, 6(1), 139–149.

Thayer, S., & Schiff, W. (1975). Eye-contact, facial expression and the experience of time. Journal of Social Psychology, 95(1), 117–124.

Weathers, R. (2005). A guide to disability statistics from the American community survey. Ithaca, NY: Employment and Disability Institute, Cornell University.

Yamada, Y., & Kawabe, T. (2011). Emotion colors time perception unconsciously. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal, 20(4), 1835–1841.

Zellner, A. (1962). An efficient method of estimating seemingly unrelated regressions and tests for aggregation bias. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 57(298), 348–368.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the U.S. National Institute of Health’s National Institute on Aging, P01 AG029409. The views expressed are those of the authors alone and do not represent their employers or funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Freedman, V.A., Conrad, F.G., Cornman, J.C. et al. Does Time Fly When You are Having Fun? A Day Reconstruction Method Analysis. J Happiness Stud 15, 639–655 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9440-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9440-0