Abstract

Adopting a general spatial framework, we analyse collusion concerning a price increase between two firms. We find that any variable affects the sustainability of collusion in the same way it affects the competitive profits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See the textbook by Motta (2004) for a very complete survey about old and new theories concerning collusion.

The relationship between product differentiation and the sustainability of collusion is exemplar of this problem. In fact, one may find a positive monotonic relationship (Chang 1991 and 1992; Hackner 1995; Miklòs-Thal 2008); a negative monotonic relationship (Friedman and Thisse 1993; Gupta and Venkatu 2002), and also a non-monotonic relationship (Deneckere 1983; Ross 1992).

However, Colombo (2011b) analyses collusion by using a spatial model which allows also for spatially asymmetric firms.

The term price schedule here refers to a positive valued function \( p(.) \) defined on S that specifies the price \( p(h) \) at which consumer h is served in equilibrium.

The case of non-optimal punishment is briefly discussed at the end of the article.

The case where the price increase is a percentage of the competitive price rather than a fixed amount yields the same results. We briefly discuss it in the Appendix.

We are restricting attention to prices such that the demand is inelastic. Clearly, whether or not demand is elastic at higher prices does not affect the results. I thank one referee for this point.

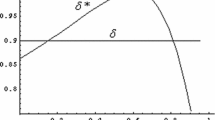

As the right-hand-side of (4) is lower than 1/2, if the market discount factor is higher than 1/2 any collusive price increase is sustainable in equilibrium. Therefore, the following Theorem 1 correctly applies only when \( \delta \leqslant {{1} \left/ {2} \right.} \).

Under the grim-trigger strategy (Friedman 1971), both firms start by charging the collusive price schedule. The firms continue to set the collusive price schedule until one firm has deviated from the collusive agreement. After a deviation has occurred, both firms play the equilibrium competitive price schedules forever.

References

Andaluz J (2010) Cartel sustainability with vertical product differentiation: price versus quantity competition. Res Econ 64:201–264

Chang MH (1991) The effects of product differentiation on collusive pricing. Int J Ind Organ 3:453–470

Chang MH (1992) Intertemporal product choice and its effects on collusive firm behaviour. Int Econ Rev 4:773–793

Colombo S (2010) Product differentiation, price discrimination and collusion. Res Econ 64:18–27

Colombo S (2011a) Taxation and predatory prices in a spatial model. Pap Reg Sci (forthcoming). doi:10.1111/j.1435-5957.2010.00342.x

Colombo S (2011b) Pricing policy and partial collusion. J Ind Compet Trade (forthcoming). doi:10.1007/s10842-010-0087-9

Colombo S (2011c) An indifference result concerning collusion in spatial frameworks. Res Econ (forthcoming). doi:10.1016/j.rie.2011.03.001

Deneckere R (1983) Duopoly super-games with product differentiation. Econ Lett 11:37–42

Espinosa MP (1992) Delivered pricing, FOB pricing and collusion in spatial markets. Rand J Econ 32:64–85

Friedman JW (1971) A non-cooperative equilibrium for super-games. Rev Econ Stud 38:1–12

Friedman JW, Thisse JF (1993) Partial collusion fosters minimum product differentiation. Rand J Econ 24:631–645

Gupta B, Venkatu G (2002) Tacit collusion in a spatial model with delivered pricing. J Econ 76:49–64

Hackner J (1995) Endogenous product design in an infinitely repeated game. Int J Ind Organ 13:277–299

Lederer PJ, Hurter AP (1986) Competition of firms: discriminatory pricing and location. Econometrica 54:623–640

Matsumura T, Matsushima N (2005) Cartel stability in a delivered pricing oligopoly. J Econ 86:259–292

Miklòs-Thal J (2008) Delivered pricing and the impact of spatial differentiation on cartel stability. Int J Ind Organ 26:1365–1380

Motta M (2004) Competition policy: theory and practice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ross T (1992) Cartel stability and product differentiation. Int J Ind Organ 10:1–13

Thisse JF, Vives X (1988) On the strategic choice of spatial pricing policy. Am Econ Rev 78:122–137

Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the helpful comments from two anonymous referees. All remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

In this appendix, we show that the result would be qualitatively the same if the price increase was a percentage of the competitive price rather than a fixed amount. Consider the collusive price schedule. Firms collude to increase the price of a percentage equal to w. It follows that the collusive price schedule is: \( p_h^C = p_h^N(1 + w) \) for all \( h \in S \). Hence, the collusive profits are: \( {\Pi^C} = \int_{{h \in {S^1}}} {[p_h^C - T(a,h)]f(h)dh} = {\Pi^N} + w\int_{{h \in {S^1}}} {p_h^Ndh} \). The deviation profits are: \( {\Pi^D} = \int_h {[p_h^C - T(a,h)]f(h)dh} = {\Pi^C} + w\int_{{h \in {S^2}}} {p_h^Nf(h)dh} \). Due to symmetry, we have: \( \int_{{h \in {S^2}}} {p_h^Nf(h)dh} = \int_{{h \in {S^1}}} {p_h^Nf(h)dh} \). Therefore, we can write: \( {\Pi^D} = {\Pi^N} + 2w\int_{{h \in {S^1}}} {p_h^Nf(h)dh} \). Using the deviation profits, the collusive profits and the punishment profits into (1), we can write the critical discount factor as follows: \( \delta * = \frac{{{\Pi^N} + 2w\int_{{h \in {S^1}}} {p_h^Nf(h)dh} - {\Pi^N} - w\int_{{h \in {S^1}}} {p_h^Ndh} }}{{{\Pi^N} + 2w\int_{{h \in {S^1}}} {p_h^Nf(h)dh} }} = \frac{w}{{1 + 2w - \Gamma }} \), where \( \Gamma = \frac{{\int_{{h \in {S^1}}} {T(a,h)f(h)dh} }}{{\int_{{h \in {S^1}}} {p_h^Nf(h)dh} }} \). However, note that the competitive profits are a decreasing function of \( \Gamma \), as the competitive profits must decrease with the transportation costs and must increase with the equilibrium competitive price. Therefore, we can conclude that the critical discount factor is inversely related to the competitive profits, as shown for a fixed amount increase of the price.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Colombo, S. Colluding on a Price Increase. J Ind Compet Trade 12, 365–371 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-011-0110-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-011-0110-9