Abstract

Members of the insect order Diptera respond differentially to environmental changes and may play an important role in understanding the effects that livestock grazing disturbances have on biodiversity. Here we examine how increasing grazing pressures on the Mongolian steppe affect Diptera diversity and abundance. Using 2334 yellow pan traps, we sampled a total of 132 sites over four years to collect 17,348 flies. We compared fly diversity and abundance at five levels of livestock grazing. We observed that fly family diversity decreased in heavily grazed sites and that diptera communities at sites with intense grazing have proportionally higher prevalence of taxa from the families Muscidae, Sepsidae, Ephydridae, Chloropidae, and Tachinidae, two of which are often associated with animal waste. Chironomidae, Ceratopogonidae, Sarcophagidae, and Sciaridae are most prevalent at sites with very little or no grazing, and Anthomyiidae, Calliphoridae, Carnidae, Cecidomyiidae, Dolichopodidae, Empididae, Scatopsidae and Sphaeroceridae are most often encountered at sites with intermediate amounts of grazing. Observing changes in a few guilds of fly families at different grazing levels is beneficial in understanding human effects on fly diversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The diversity of Diptera, a major group in terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems, can tell us much about how organisms respond to environmental disturbance. Understanding how environmental disturbance events affect biological diversity remains an active area of research in community ecology (Moctezuma et al. 2016; Solar et al. 2016). One such anthropogenic impact on the environment, livestock grazing, can be particularly detrimental to biological communities, especially in concentrated amounts (Papanastasis et al. 2017), but recognizing the consequences of slight or moderate grazing on the biodiversity of a community can be challenging. Livestock grazing results in the removal of ground cover, the deposition of fecal matter, and the compaction of soil, which can severely degrade habitats especially in combination with watershed and stream channel erosion (Yadamsuren et al. 2015). This overuse of land often results in significant reductions in diversity and productivity in both plants and animals (Milton et al. 1994), but can also lead to the opposite outcome in terms of biotic diversity. Increasing available resources, such as fecal matter, can increase arthropod diversity by adding new niches (Verdú et al. 2000). However, converting a diversity of resources to this single “fecal” resource could decrease habitat heterogeneity and thus niches available to diverse arthropods. Because specialists exist at both high and low levels of grazing, the intermediate disturbance hypothesis suggests that, in fact, the greatest amount of diversity should be found at intermediate levels of disturbance (Connell 1978). These different biotic responses make it difficult to gauge the effect that livestock grazing has on biodiversity as a whole. We therefore examine the effect that grazing has on one particularly diverse group of invertebrates, the insect order Diptera (true flies).

Invertebrates are overwhelmingly dominant in abundance and niche diversity in most biotic communities and for this reason provide a good avenue for analyzing the effect of overgrazing on an ecosystem (Taylor and Doran 2001). In some heavily grazed areas, invertebrate diversity is low, but the abundance of a few taxa is much higher than in lightly grazed areas (Seymour and Dean 1999), probably because many invertebrates, including flies, are saprophagous or coprophagous by nature. Many flies rely on excrement provided by livestock for nutrition and reproduction, and thereby increase in population with increased grazing (McAlpine et al. 1981). The enhancement of the detritivore and decomposer resources and cycles could increase the number of exploiting taxa.

As some of the most abundant and diverse invertebrates, true flies have been used to monitor ecological pressures (Servia et al. 1998; Haslett 2001; Cabrini et al. 2013). Among adult aquatic insects found on Mongolian streambanks, Diptera were most significantly affected by livestock grazing and erosion resulting in a decrease in richness (Hayford and Gelhaus 2010). Crane flies (Tipuloidea) in particular were negatively impacted by grazing in Mongolia because of decreased plant biomass and desiccation of moss, a common larval habitat (Yadamsuren et al. 2015). Soil-dwelling Diptera have also been used as effective bioindicators because of the role they play in decomposition, their widespread abundance, and their niche similarity to other soil-dwelling species (Frouz 1999). Where manure is present, there is an increase in abundance of soil-dwelling larvae, especially in the families Chironomidae, Sciaridae, Scatopsidae and Psychodidae (Frouz 1999). However, the effect that heavy grazing has on adult fly taxonomic families and family diversity is unknown.

Mongolia has an array of diverse and, as yet, lightly polluted environments. With its low population density and varied biogeographical landscape, it has retained much of the biota that has been lost in surrounding more populous Asian countries (Fernandez-Gimenez 2000). Nomadic grazing has been prominent in Mongolia for centuries, including ruminants such as yaks, sheep, goats and cattle, and non-ruminating horses and camels (Johnson et al. 2006). The recent increase in the price of cashmere and privatization of land has led to domestic grazing becoming commercialized with heavier grazing in more areas (Mearns 2004; Maasri and Gelhaus 2011). This recent transition lends an opportunity to observe the short-term effects of grazing in Mongolia (Maasri and Gelhaus 2011).

We investigated the effect of grazing pressure on terrestrial adult fly diversity and abundance to test whether flies can be used as bioindicators to evaluate human impact on habitats in the Mongolian steppe and taiga. Because aquatic flies responded negatively to streambank erosion (Hayford and Gelhaus 2010) which is closely related to grazing, we hypothesize that terrestrial adults have a measured response to grazing pressures as well. This response could be negative—meaning that fly diversity decreases in response to increased grazing pressures, intermediate—meaning that fly diversity is highest in areas that are moderately grazed, or positive—indicating that fly diversity is greatest in areas that have been heavily grazed. These response categories can also be applied at the family level, comparing how frequently a family is encountered at the above grazing intensities. We asked which families of flies are most heavily affected by grazing and which are best used as bioindicators of grazing pressures and found a diversity of responses in the fly families examined.

Materials and methods

Study area

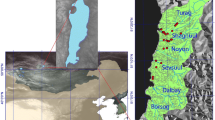

We sampled fly communities near streams and rivers from sites across northern Mongolia (Fig. 1; Table 1) as part of a larger general aquatic ecology survey of more than 400 sites called the Mongolian Aquatic Insect Survey (MAIS). This is an effort led by a group of international and Mongolian scientists to inventory aquatic insect diversity in the mountainous regions of Mongolia. As we visited these sites we also quickly sampled the terrestrial community. Collecting sites for this study were distributed primarily in the Altai range of western Mongolia, the Hangai range of central Mongolia, and the Onon river drainage of eastern Mongolia, and were sampled in July for four consecutive years (2008–2011). We selected sites based largely on relative ease of access on loops of rough roads that included many habitat types.

At each site, we sampled insect communities and took measurements of habitat conditions and biochemistry. Grazing intensity at each site was scored from 0 to 4 using a standardized rubric based on vegetation height and the composition of the grass community (Table 2). This minimized sampling bias by different researchers, an imperative as team members varied over the course of this project.

We collected insects at each site using yellow pan traps, a simple, cost-effective method to sample riparian flies (Vrdoljak and Samways 2012). With this approach, many flying insects, including flower-visiting guilds of insects as well as adults of aquatic insects, were trapped in a low-effort, high-yield manner. Yellow plastic 12 oz bowls (SOLO® Number PSB2Y-0099) were placed in a line of pans parallel to the riverbank at 10 m intervals, usually less than 1 m from the water, and filled with water and a dish soap surfactant. The number of pans placed at each site varied over the 4 years, with 20–25 per site for the first 2 years, and 10 per site during the last 2 years. This sampling variation was accounted for in diversity analysis by extrapolating rarefaction curves to the same maximum (25 pans per site) using EstimateS version 9 (Colwell 2013). Down-sampling also assisted in accounting for differences in the number of sites at each grazing level. The pans were left undisturbed for 1 h of daylight, and then specimens were collected. All trapping was done during the daytime without storms, although control for uniform temperatures, weather conditions, and time of day was not possible. We sorted dipteran specimens to family; more specific taxon sorting could add resolution to our analysis, but was impractical given the number of specimens and time available for this analysis. We vouchered specimens from this study in the alcohol collection under Diptera in the M. L. Bean Life Science Museum at Brigham Young University. They are stored in 70% ethanol, in general with only one family per vial but perhaps more than one species in a vial.

Analysis

We generated sample-based rarefaction curves using EstimateS (Colwell 2013) to evaluate the effectiveness of our sampling at representing fly diversity for each level of grazing (Fig. 2). Species area/effort theory predicts that taxa will increase with effort up to a point of saturation of habitat, niche, or geographic footprint (Srivastava 1999; Gotelli and Colwell 2001), and we were interested in how close our efforts had come to saturation at each grazing level. The Est(S) function in EstimateS uses the reference sample to compute the expected number of different species in a given number of pooled samples (Colwell 2013). Each sample was represented by the number of flies or families of flies found in a single trap. We extrapolated each of the rarefaction curves to a total of 780 traps, corresponding to the total number of traps in our largest category (slight grazing) to account for uneven sampling. A grazing level was considered sampled to near-saturation if the number of observed families was more than 95% of what was expected after 780 traps. We randomized each curve with 100 sample order randomization runs with the EstimateS function, and compared the difference in rarefaction curves of family diversity at different grazing levels. If the 84% confidence intervals of the curves of different grazing levels did not overlap, a difference was considered significant (Fig. 3). This metric mimics P < 0.05 statistical testing more realistically than stricter confidence intervals (MacGregor-Fors and Payton 2013).

Sample-based species accumulation curves for the five levels of grazing. Dashed lines indicate where data was extrapolated. Black diamonds indicate where curves reach near saturation with 95% of the diversity. Curves generated using the S(est) function in EstimateS (Colwell 2013)

Diptera family richness for different grazing intensities with an 84% confidence interval as a response to effort at 90 pans (number at least-sampled grazing level), 300 pans, 500 pans and 780 pans (number at most-sampled grazing level). Diversity metrics have been extrapolated to show expectations under a uniform sampling effort using EstimateS

To analyze the effect of grazing intensity on terrestrial fly diversity, we compared fly abundance and family richness for each level of grazing using analysis of variance (ANOVA) in R version 3.2.2 (R Core Team 2013). We also used EstimateS to compare diversity differences extrapolated for maximum or minimum real sampling effort (e.g., to 25 pans per site or with only 9 sites from each grazing level).

We evaluated how each family responded to different grazing pressures by grouping taxa into four categories based on the slope estimated from a linear regression model of that family’s prevalance versus grazing intensity (Table 3; Fig. 4). If the slope was less than − 0.03, it was scored as having a negative response to grazing, being most prevalent at less-grazed sites (Fig. 4; Ceratopogonidae). If the slope was between − 0.03 and 0.03 and the average frequency of the fly family was at least 10% higher in intermediately-grazed areas (slight grazing, moderate grazing, or mixed grazing) than at the two extremes of grazing (no and heavy), we categorized it as having an intermediate response, being most abundant at middle amounts of grazing (Fig. 4; Anthomyiidae). If the slope was greater than 0.03, the family was considered to have a positive response to grazing pressures, being more prevalent at heavily grazed areas (Fig. 4; Ephydridae). Finally, a family with a slope between − 0.03 and 0.03 and with prevalence at middle grazing pressures less than 10% higher than at extremes was categorized as having no response (Fig. 4; Phoridae). Data-deficient taxa (a family with fewer than 10 individuals collected) were not categorized as their rarity would not allow for robust statistical testing. The thresholds for slope categories were set at − 0.03 and 0.03 because families with slopes > 0.03 or < − 0.03 also had correlation coefficients > 0.5 and < − 0.5 respectively.

Example of differential responses of select Diptera families to grazing pressure as gathered from yellow pan traps in Mongolia. Ceratopogonidae displays a negative response to increased grazing pressure. Anthomyiidae is most prevalent in areas of intermediate disturbance. Ephydridae shows a positive response to increased grazing pressures, and Phoridae has a negligible response to grazing. Dotted lines represent line of best fit. Solid lines connect values from different grazing pressures

Results

We visited 132 different sites and set up 2334 pan traps to collect 17,348 flies. This yielded, on average, 7.0 flies per trap (ranging from 0 to 115) and 2.6 different families in each trap. Of the 155 recognized families of Diptera (Marshall 2012), 49 were represented in our samples (Table 3). A third of the individuals we collected were Chironomidae (5858 from 112 sites). Other prominent families were Ephydridae (2459 from 112 sites), Dolichopodidae (2273 from 105 sites), Muscidae (1922 from 105 sites), Anthomyiidae (723 from 86 sites), Chloropidae (688 from 90 sites), Phoridae (587 from 53 sites), Tachinidae (309 from 58 sites) and Sciaridae (303 from 76 sites). In all, 87% of the flies we collected were from these nine families. Six families were collected as a single individual: Aulacigastridae, Conopidae, Lonchopteridae, Opomyzidae, Sciomyzidae, and Therevidae. Most of the 49 families we collected had intermediate levels of abundance between 10 and 300 individuals. The families that were encountered at the highest frequencies also had the greatest abundance (Fig. 5).

Sampling effectiveness

The richness accumulation curves showed that we collected enough samples to reach near-saturation values of 95% or more of the total extrapolated diversity for each grazing level except no grazing, where we collected only 63% of the diversity (Fig. 2). Our sampling yielded 26 diferent families from ungrazed sites (from 90 pans), 40 different families from sites with slight grazing (780 pans), 40 families from sites with moderate grazing (636 pans), 36 families from sites with mixed grazing (508 pans) and 24 families from sites with heavy grazing (122 pans).

Richness and abundance across a grazing gradient

The overlapping 84% confidence intervals of our extrapolated species effort curves (Fig. 3) indicate that heavily grazed sites have lower overall fly family diversity than sites with intermediate levels of grazing (e.g., slight, moderate, and mixed). The confidence interval for ungrazed sites remained extremely broad (likely due to the small true sample size for this category), and overlapped with the confidence interval for heavily grazed sites. These relationships remained consistent at both our simulated high and low sampling schemes (e.g., 780 pans, the maximum at any category, and 90 pans, the minimum at any category). Similarly, without extrapolation, mean numbers of fly families at sites with intermediate grazing levels (slight: 8.88, moderate: 8.85, mixed: 8.96) are higher than the average number of flies at heavy grazing (8.18) and no grazing (8.44), however, these were not statistically significant (ANOVA, F = .2218, df = 4, p = 0.9258).

Average overall Diptera abundance was greater at sites with grazing than at sites with no grazing (Fig. 6), but these differences were not statistically significant (ANOVA, F = 0.349, df = 4, p = 0.8443).

Taxonomic response to grazing

Different fly families spanned the variety of possible responses to livestock grazing pressure (Table 3; Fig. 4). Four families (Chironomidae, Sciaridae, Ceratopogonidae and Sarcophagidae) decreased in frequency as grazing increased, eight families (Dolichopodidae, Anthomyiidae, Empididae, Sphaeroceridae, Cecidomyiidae, Calliphoridae, Carnidae, and Scatopsidae) were most prevalent at intermediate grazing, and five families (Ephydridae, Muscidae, Chloropidae, Tachinidae and Sepsidae) increased in frequency as grazing increased. In addition, 32 families had no responses to grazing or did not have enough specimens collected to make conclusive judgements about patterns. However, in the 23 families where 20 or fewer specimens were collected, only three of them, Pipunculidae, Tabanidae, and Aulacigastridae, were collected in areas with heavy grazing. Of the nine most abundant families, all but Phoridae showed a positive, negative, or intermediate response.

Discussion

Our project represents the most complete effort thus far to document flies in Mongolia. In our 17,348 flies, we encountered 49 different families. This is comparable to the results of similar surveys done in Australian rain forests where 56 families were found from 28,647 flies (Kitching et al. 2004) or in a forested national park in Germany where 62 families were found among 19,641 individuals (Scherber et al. 2014).

An overall aim of the project was to collect fly families at every site that had been chosen by the MAIS survey. We had no expectation of sampling lightly and heavily sites equally, and in the end had more moderately grazed sites than ungrazed or heavily grazed sites, so it was necessary to rarify our data for comparison. This analysis shows that fly diversity at our sites in Mongolia is greater at intermediate levels of grazing (slight, moderate, mixed) than in heavily grazed areas. This may be consistent with Connell’s intermediate-disturbance hypothesis (1978) or with a decrease in diversity with increased grazing. At sites with heavy grazing, there is less variation in family diversity and fewer families than at sites with intermediate levels of grazing. However, streams where no grazing was observed have a high variation in fly family diversity that is sometimes as low as the heavily grazed sites. More ungrazed streambanks need to be sampled to better resolve the impact of grazing in this environment, though locating such sites may be difficult as commercialized herding spreads across the country.

In contrast to the decrease in family diversity, Diptera abundance increased in sites where at least some grazing was present. Part of this rise was due to immense abundance increases for specific families at single sites. For example, in the family Phoridae, 587 individuals were collected throughout the course of the study, of which 324 were collected from a single heavily grazed site. This is one of the most ecologically diverse groups of flies, and it is not unheard of for this family to dominate the abundance at a particular site (Brown 2005). At another site that had mixed grazing, 828 Chironomidae individuals were collected. Additionally, 209 of the 243 Psychodidae individuals were also collected from a single site with mixed grazing. Both of these families have members that are especially well-adapted to anoxic environments as larvae (Boltz et al. 2008), which may explain their high abundance in areas where grazing mammals provide the necessary habitat in a localized manner (Verdú et al. 2000). Such single-site superabundances can skew observed trends, so it is important to be mindful of the influence of outliers on parametric statistics when studying highly heterogeneous ecological systems.

Four of the five families that increased in abundance with grazing pressures, Ephydridae, Muscidae, Tachinidae and Sepsidae, are commonly found in connection with animal biproducts such as carrion or animal excrement (McAlpine et al. 1981). The fifth, Chloropidae, is mainly a plant feeder, but includes many saprophagous species which often suck up liquid secretions and tend to mass around animals, including at least one genus that feeds in excrement or dead animals (Oldroyd 1965; Ismay and Nartshuk 2000). As more livestock are grazed, greater amounts of animal excrement provide habitat for these families. However, many other dung-feeding or dung-breeding families like Calliphoridae, Sphaeroceridae, Scatopsidae, Phoridae, Psychodidae, Carnidae and Sarcophagidae did not increase with increased grazing. In fact, Calliphoridae was not collected at any sites with heavy grazing, and Sarcophagidae responded negatively to increased grazing. Following a disturbance, insects that are more tolerant to stress may dominate a community (Schowalter 2012), which may explain why some taxa ostensibly adapted for the byproducts of grazing nevertheless found themselves shunted into a minor role.

The families that responded negatively to increased grazing pressure (Chironomidae, Sciaridae, Sarcophagidae, and Ceratopogonidae) are found in a variety of habitats. Most Chironomidae are aquatic as larvae, but as terrestrial adults live on a variety of substrates, Sciaridae are often vegetable feeders or live on fungi, Sarcophagidae feed on flesh or carrion, and Ceratopogonidae feed on either other insects or mammals (Oldroyd 1965; McAlpine et al. 1981). Each of these families have members that inhabit a wide variety of niches but all of these habitats could be degraded or impacted with increased grazing pressures.

In aquatic assessment protocols, Chironomidae have historically been used as indicators of high levels of disturbance or stress (Pinder 1986; Plafkin et al. 1989), often the dominant macroinvertebrate in heavily polluted habitats (Winner et al. 1980). However, the group is taxonomically diverse and Chironomidae species can be found in almost every body of freshwater (Pinder 1986), so characterizing all of Chironomidae as “tolerant” of pollution or disturbances is an over-generalization. Although chironomids were prevalent in high numbers at a majority of our sites, they showed the greatest affinity for sites where there was low or intermediate amounts of grazing. We suspect that the rich abundance and diversity of aquatic forms of chironomids at our sites may swamp any signal from the less diverse soil inhabiting guild of these flies that has occasionally been reported in previous ecological surveys (Frouz 1999).

The family where we observed the most dramatic negative response to livestock grazing is Ceratopogonidae, the “biting midges”. Diptera from this family were present at more than 50% of ungrazed or slightly grazed sites, while we encountered them only twice in our 18 heavily grazed sites. Members of this family have been found to be responsive to pesticides in other habitats (Rochlin et al. 2011) and this may reflect their susceptibility to other environmental disturbances such as grazing, and potential as bioindicators of acceptable levels of grazing.

We were surprised by a lack of response in several families where a response was expected. For example, aquatic crane flies in Mongolia responded negatively to grazing pressures in a previous stucdy (Yadamsuren et al. 2015), but we encountered them at similar frequencies across all levels of grazing. This may be because the larvae respond differently than the adults or because this effect can only be seen at the species level.

The families with the most visible responses to grazing were Ceratopogonidae as an indicator of low grazing pressures and Ephydridae and Muscidae as indicators of heavy grazing. We recommend these families as indicators of grazing pressures. Future research should focus on further evaluating these families as bioindicators in areas with similar or distinct biota. These families could also be the focus of future work at the species level.

In conclusion, the consequences of large livestock mammal grazing on fly populations in Mongolia are complex and tailored to individual taxonomic groups, but overall, heavy grazing has a negative effect on fly diversity at the family level. The same pattern is likely reflected at the species level, but we need more intensive field experiments to begin to speculate the reasons why. Although many fly families have members that are part of several different guilds and it may be easier to measure guilds within families, differences in habitat preferences have been documented in guilds of fly families (Hughes et al. 2000), and we can begin to see the makeup of these guilds in the results of our study. As levels of commercial grazing continue to increase in Mongolia, many populations of flies, especially those dependent on low levels of grazing are vulnerable. Understanding fly diversity metrics and taxonomic guilds is important to understanding the effect that grazing disturbances have on biodiversity as a whole and may be useful for evaluating land use.

References

Boltz JP, Goodwin SJ, Rippon D, Daigger GT (2008) A review of operational control strategies for snail and other macrofauna infestations in trickling filters. Water Pract 2:1–16. https://doi.org/10.2175/193317708X335181

Brown VB (2005) Malaise trap catches and the crisis in neotropical dipterology. Am Entomol 51:180–183. https://doi.org/10.1093/ae/51.3.180

Cabrini I, Grella MD, Andrade CFS, Thyssen PJ (2013) Richness and composition of Calliphoridae in an Atlantic Forest fragment: implication for the use of dipteran species as bioindicators. Biodivers Conserv 22:2635–2643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-013-0545-x

Colwell RK (2013) EstimateS: statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples. Version 9 and earlier. User’s Guide and application. http://purl.oclc.org/estimates

Connell JH (1978) Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. Science 199:1302–1310. https://doi.org/10.2307/1745369

de Castro Solar RR, Barlow J, Andersen AN et al (2016) Biodiversity consequences of land-use change and forest disturbance in the Amazon: a multi-scale assessment using ant communities. BIOC 197:98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.03.005

Fernandez-Gimenez ME (2000) The role of mongolian nomadic pastoralists’ ecological knowledge in rangeland management. Ecol Appl 10:1318–1326

Frouz J (1999) Use of soil dwelling Diptera (Insecta, Diptera) as bioindicators: a review of ecological requirements and response to disturbance. Agric Ecosyst Environ 74:167–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8809(99)00036-5

Gotelli NJ, Colwell RK (2001) Quantifying biodiversity: procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol Lett 4:379–391. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00230.x

Haslett JR (2001) Biodiversity and conservation of Diptera in heterogeneous land mosaics: a fly’s eye view. J Insect Conserv 5:71–75. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011321005040

Hayford B, Gelhaus J (2010) The relationship between grazing and erosion and adult aquatic insect metrics in streams of outer Mongolia. Mong J Biol Sci 8:27–39. https://doi.org/10.22343/mjbs.2010.08.04

Hughes JB, Daily GC, Ehrlich PR et al (2000) Society for conservation biology conservation of insect diversity: a habitat approach conservation of insect diversity: a habitat approach. Conserv Biol 14:1788–1797. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2000.99187.x

Ismay JW, Nartshuk EP (2000) Family chloropidae. In: Papp L, Darvas B (eds) Manual or palearctic diptera. Science Herald, Budapest, pp 382–430

Johnson DA, Sheehy DP, Miller D, Damiran D (2006) Mongolian rangelands in transition. Secheresse 17:133–141

Kitching RL, Bickel D, Creagh AC et al (2004) The biodiversity of diptera in old world rain forest surveys: a comparative faunistic analysis. J Biogeogr 31:1185–1200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.01096.x

Maasri A, Gelhaus J (2011) The new era of the livestock production in Mongolia: consequences on streams of the great lakes depression. Sci Total Environ 409:4841–4846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.08.005

MacGregor-Fors I, Payton ME (2013) Contrasting diversity values: statistical inferences based on overlapping confidence intervals. PLoS ONE 8:8–11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056794

Marshall SA (2012) Flies: the natural history & diversity of Diptera. Firefly Books, Richmond Hill

McAlpine JF, Peterson BV, Shewell GE et al (1981) Manual of nearctic diptera. vol 1, Biosystematics Research Institute, Agriculture Canada, Ottawa

Mearns R (2004) Sustaining livelihoods on Mongolia’s pastoral commons: insights from a participatory poverty assessment. Dev Change 35:107–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2004.00345.x

Milton SJ, Dean WRJ, du Plessis MA, Siegfried WR (1994) A conceptual model of arid rangeland degradation. Bioscience 44:70–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/1312204

Moctezuma V, Halffter G, Escobar F (2016) Response of copronecrophagous beetle communities to habitat disturbance in two mountains of the Mexican Transition Zone: inluence of historical and ecological factors. J Insect Conserv 20:945–956. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-016-9923-5

Oldroyd H (1965) The natural history of flies. Norton, New York

Papanastasis VP, Bautista S, Chouvardas D et al (2017) Comparative assessment of goods and services provided by grazing regulation and reforestation in degraded Mediterranean rangelands. Land Degrad Dev 28:1178–1187. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2368

Pinder LCV (1986) Biology of freshwater chironomidae. Annu Rev Entomol 31:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.31.010186.000245

Plafkin JL, Barbour MT, Porter KD et al (1989) Rapid bioassessment protocols for use in stream and rivers: benthic macroinvertebrates and fish. U.S. Environ. Prot. Agency, Assess. Watershed Prot. Div. Off. Water Regul. Stand. Washington, D.C. EPA 440-4-89-001. p 150

R Core Team (2013) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Core Team, Vienna

Rochlin I, Dempsey ME, Iwanejko T, Ninivaggi DV (2011) Aquatic insects of new york salt marsh associated with mosquito larval habitat and their potential utility as bioindicators. J Insect Sci 11:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1673/031.011.17201

Scherber C, Vockenhuber EA, Stark A et al (2014) Effects of tree and herb biodiversity on diptera, a hyperdiverse insect order. Oecologia 174:1387–1400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-013-2865-7

Schowalter TD (2012) Insect responses to major landscape-level disturbance. Ann Rev Entomolo 57(1):1–20

Servia MJ, Cobo F, Gonzalez MA (1998) Deformities in larval Prodiamesa olivacea (Meigen, 1818) (Diptera, Chironomidae) and their use as bioindicators of toxic sediment stress. Hydrobiologia 385:153–162

Seymour CL, Dean WRJ (1999) Effects of heavy grazing on invertebrate assemblages in the Succulent Karoo, South Africa. J Arid Environ 43:267–286. https://doi.org/10.1006/jare.1999.0552

Srivastava DS (1999) Using local-regional richness plots to test for species saturation: pitfalls and potentials. J Anim Ecol 68:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.1999.00266.x

Taylor RJ, Doran N (2001) Use of terrestrial invertebrates as indicators of the ecological sustainability of forest management under the Montreal process. J Insect Conserv 5:221–231. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013397410297

Verdú JR, Crespo MB, Galante E (2000) Conservation strategy of a nature reserve in Mediterranean ecosystems: the effect of protection from grazing on biodiversity. Biodivers Conserv 9:1707–1721. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:102650672

Vrdoljak SM, Samways MJ (2012) Optimising coloured pan traps to survey flower visiting insects. J Insect Conserv 16:345–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-011-9420-9

Winner RW, Boesel MW, Farrell MP (1980) Insect Community structure as an index of heavy-metal pollution in lotic ecosystems. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 37:647–655. https://doi.org/10.1139/f80-081

Yadamsuren O, Hayford B, Gelhaus J et al (2015) Declines in diversity of crane flies (Diptera: Tipuloidea) indicate impact from grazing by livestock in the Hovsgol region of Mongolia. J Insect Conserv 19:465–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-015-9767-4

Acknowledgements

We thank directing members of the Mongolian Aquatic Insect Survey, listed below, for their support in this project. We also thank the participants and support staff of the Mongolian Aquatic Insect Survey. We thank members of the Nelson Laboratory at Brigham Young University, especially Joss Wertz, who collected the first year of data for this project. We thank the Roger and Victoria Sant Endowment for a Sustainable Environment (Brigham Young University) for providing funding for this project to get students into the unfamiliar territory of central Asia. We gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the US National Science Foundation (DEB-BSI #0743732, “Survey and Inventory of the Aquatic Macroinvertebrates of the Altai and Hangai Mountain drainages, Mongolia”, to J. Gelhaus, J. Morse, C. R. Nelson) for direct support of this fly diversity research and to (DEB-BSI #0206674, “Survey and Inventory of the Aquatic Macroinvertebrates of the Selenge River, Mongolia” to J. Gelhaus, J. Morse, B. Hayford), and (DEB-BS&I #0816910, “An Ecological Guild-Based Biodiversity Inventory and Survey of the Aquatic Non-biting Midges (Diptera: Chironomidae) of the Altai and Hangai Mountain Drainages, Mongolia” to B. Hayford) for supporting work. Our studies were conducted under the arching support of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Clemson University, Brigham Young University, and Wayne State College. We give special thanks to Jon Gelhaus, Barbara Hayford, the late Sarah Walker Judson, Jigmed Khandsuren “Handaa”, Alain Maasri, John Morse, Sigitas Podenas, Virginija Podeniene, Chuluunbat Suvdtsetseg, Sundarea, Enkhnasan Davaadorj for their field help and the entire MAIS team for their hard work and diligence. We give our highest thanks and respect to the late Balgan Namkhaidorj for his professional entomological guidance, his uncanny geographical knowledge, and his direct material safety mentoring during our expeditions as we bounced across the steppe and taiga. Goodbye friend, bayarlalaa. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the US National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Clement, R.A., Frandsen, P.B., McKnight, T. et al. Fly family diversity shows evidence of livestock grazing pressure in Mongolia (Insecta: Diptera). J Insect Conserv 22, 231–243 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-018-0056-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-018-0056-x