Abstract

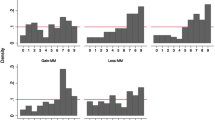

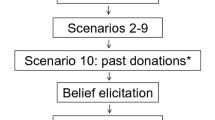

Several papers have documented that when subjects play with standard laboratory “endowments” they make less self-interested choices than when they use money they have either earned through a laboratory task or brought from outside the lab. In the context of a charitable giving experiment we decompose this into two common artifacts of the laboratory: the intangibility of money (or experimental currency units) promised on a computer screen relative to cash in hand, and the distinct treatment of random “windfall” gains relative to earned money. While both effects are found to be significant in non-parametric tests, the former effect, which has been neglected in previous studies, has a stronger impact on total donations, while the latter effect has a greater impact on the probability of donating. These results have clear implications for experimental design, and also suggest that the availability of more abstract payment methods may increase other-regarding behavior in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Arabmazar, A., & Schmidt, P. (1981). Further evidence on the robustness of the Tobit estimator to heteroskedasticity. Journal of Econometrics, 17(2), 253–258.

Breman, A. (2006). Give more tomorrow: evidence from a randomized field experiment. Unpublished manuscript.

Carlsson, F., He, H., & Martinsson, P. (2009). Easy come, easy go—the role of windfall money in lab and field experiments (Working Papers in Economics 374).

Cherry, T., & Shogren, J. (2008). Self-interest, sympathy and the origin of endowments. Economics Letters, 101(1), 69–72.

Cherry, T., Frykblom, P., & Shogren, J. (2002). Hardnose the dictator. American Economic Review, 92(4), 1218–1221.

Cherry, T., Kroll, S., & Shogren, J. (2005). The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on public good contributions: evidence from the lab. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 57(3), 357–365.

Clark, J. (2002). House money effects in public good experiments. Experimental Economics, 5(3), 223–231.

Cookson, R. (2000). Framing effects in public goods experiments. Experimental Economics, 3(1), 55–79.

Eckel, C., & Grossman, P. (1996). Altruism in anonymous dictator games. Games and Economic Behavior, 16(2), 181–191.

Eckel, C., & Grossman, P. (1998). Are women less selfish than men?: evidence from dictator experiments. The Economic Journal, 108(448), 726–735.

Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J., Savin, N., & Sefton, M. (1994). Fairness in simple bargaining games. Games and Economic Behavior, 6(3), 347–369.

Gourieroux, C., Monfort, A., & Trognon, A. (1984). Pseudo maximum likelihood methods: applications to Poisson models. Econometrica, 52(3), 701–720.

Harrison, G. (2007). House money effects in public good experiments: Comment. Experimental Economics, 10(4), 429–437.

Hoffman, E., & Spitzer, M. (1985). Entitlements, rights, and fairness. Journal of Legal Studies, 14(2), 259–297.

Hoffman, E., McCabe, K., Shachat, K., & Smith, V. (1994). Preferences, property rights, and anonymity in bargaining games. Games and Economic Behavior, 7(3), 346–380.

Hoffman, E., McCabe, K., & Smith, V. (1996). Social distance and other-regarding behavior in dictator games. American Economic Review, 86, 653–660.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J., & Thaler, R. (1991). Anomalies: the endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 193–206.

Kroll, S., Cherry, T., & Shogren, J. (2007). The impact of endowment heterogeneity and origin on contributions in best-shot public good games. Experimental Economics, 10(4), 411–428.

List, J. (2004). Young, selfish and male: field evidence of social preferences. The Economic Journal, 114(492), 121–149.

Locke, J. (1988). Two treatises of government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Loomes, G., & Burrows, P. (1994). The impact of fairness on bargaining behaviour. Empirical Economics, 19, 201–221.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: a theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633–644.

Mittone, L., & Ploner, M. (2006). Is it just legitimacy of endowments? an experimental analysis of unilateral giving (CEEL Working Paper N. 02/2006).

Niederle, M., & Vesterlund, L. (2007). Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1067–1101.

Oberholzer-Gee, F., & Eichenberger, R. (1999). Focus effects in dictator game experiments.

Oberholzer-Gee, F., & Eichenberger, R. (2004). Fairness in extended dictator game experiments. Manuscript.

Oxoby, R., & Spraggon, J. (2008). Mine and yours: property rights in dictator games. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organisation, 65, 703–713.

Papke, L., & Wooldridge, J. (1996). Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401 (k) plan participation rates. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11(6), 619–632.

Rabin, M. (1993). Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. American Economic Review, 83(5), 1281–1302.

Ruffle, B. (1998). More is better, but fair is fair: tipping in dictator and ultimatum games. Games and Economic Behavior, 23(2), 247–265.

Rutstrom, E., & Williams, M. (2000). Entitlements and fairness: an experimental study of distributive preferences. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 43(1), 75–89.

Sheffrin, H., & Thaler, R. (1988). The behavioral life-cycle hypothesis. Economic Inquiry, 26, 609–643.

Thaler, R. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4, 199–214.

Thaler, R., & Johnson, E. (1990). Gambling with the house money and trying to break even: the effects of prior outcomes on risky choice. Management Science, 36, 643–660.

Vohs, K., Mead, N., & Goode, M. (2006). The psychological consequences of money. Science, 314, 1154–1156.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reinstein, D., Riener, G. Decomposing desert and tangibility effects in a charitable giving experiment. Exp Econ 15, 229–240 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-011-9298-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-011-9298-0

Keywords

- House money effect

- Experimental methodology

- Tangibility

- Public goods

- Charitable giving

- Individual choice

- Altruism