Abstract

This paper presents an agent-based model of the labor market. It simulates the market in the recent period at the aggregate level and at the level of the principal categories of labor, on the basis of the decisions of heterogeneous agents, firms and individuals, who interact. These decisions rely on individual computations of profits and utilities, although rationality is bounded in such a complex environment. The theoretical structure that underlies the decisions is the search concept. We apply this framework to the case of France in 2011. The model is at a scale of 1/4700. It is fairly detailed on the institutions of the labor market that constrain the agents’ decisions. Finally it is calibrated by a powerful algorithm to reproduce a large number of variables of interest. The calibrated model presents a consistent accounting system of the gross flows of the individuals between the main states, employment, distinguishing open ended contracts and fixed duration contracts, unemployment and inactivity. The simulation of the gross flows accounts enables us to analyze the patterns of mobility in a way that the observed statistics on gross flows, which are partial, cannot do. The model then characterizes the nature of the labor market under study, reproducing the high proportion of the fixed duration contracts in the hiring flows, and it points to a dualism of the French labor market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For evidence of the bias introduced by a matching function as a result of an employment policy, see Neugart (2008).

The diversity of contracts exists in many other countries and the model could be adapted to simulate other labor markets.

Artifacts in multi-agent systems are the passive (non-proactive) entities providing the services and functions that make individual agents work together Omicini et al. (2008), and must be differed from proactive autonomous entities like the individuals or the firms.

Main FDC Features: maximum duration of 18 months with the possibility to go to 24 months in some cases, including the possibility to be renewed once, a small probationary period and allowance at the end of the contract: 10 % of total gross salary. Cannot be broken without heavy penalties (paying the remaining salary part).

Main OEC Features: no duration limit, probationary period, no firing costs for the first year, no termination costs if quitting, variable firing costs when firing.

One week is necessary to account for very short term contracts that are common in France.

Compared with the previous version of WorkSim (Lewkovicz and Kant 2008), the present version introduces experience factors and imperfect information.

This complementariness is justified by several economic studies. The complementarity in terms of performance between a technological level of a job (related to implicit physical capital associated) and a level of human capital used is a common accepted fact (Leiponen 2005), even if it should be qualified. The complementarity between general human capital and specific human capital has the following theoretical basis: the general human capital of an individual allows him to better utilize her specific knowledge (Ballot and Taymaz 1997; Acemoglu and Pischke 1999).

We have made the choice to discard the notion of firm human specific capital by creating instead two new types of human capitals. The first is the occupation human capital, which corresponds to the professional skills acquired in the educational system and subsequent experience acquired in a given occupation level. This type of human capital is obviously important and distinct from work experience since entering the labor market in the model (see Gibbons et al. (2005); Kambourov and Manovskii (2009); for evidence). In the model it is specific to a broad aggregate of occupations q, but it could be extended to more finely defined professions or crafts. The second is the job specific human capital. It covers possibly some required training given when entering the job but in any case the experience by learning on the job. It is assumed to be so specific that it will not have any use in other jobs. It notably contains some social skills specific to the job.

These increases in productivity corresponds to the learning by doing phenomena highlighted by Arrow (1962) and represent increases in productivity without training costs for the firm.

This is to model the impact of skills forgotten due to a too long period of unemployment or inactivity.

Note that when the firm consists only of its managing director or the managing director with one employee, the firm knows its global production \(Q_{j,t}\) and does not have any doubt on the effective productions; therefore \({\sigma }_{i,j,q,p,t}=0\).

As for “Salaire minimum interprofessionnel de croissance”. In 2011, the monthly net minimum wage for a full-time job was 1 072 €.

Moreover, in terms of theoretical consistency, it is necessary to choose a posted salary and not a salary negotiated on the basis of the match value. The matching theory usually chooses the latter, but the search theory involves the assumption of a distribution of salaries offered by companies, which leads job seekers to evaluate jobs and apply for them (or not).

See e.g. Lindbeck and Snower (1988). Note that very strong recessions like the 2008 recession might justify to qualify this hypothesis at the level of some firms.

The labor cost represents here the capital funds the firm has to pay in advance. Hence, the return is the ratio of the profit over this capital.

Very little attention has been brought to optimal search theory by firms, certainly because matching theory has replaced the detailed decision based approach of search theory that could consider heterogeneous firms by a representative agent approach. Pissarides (1976, pp. 37–41) is an exception and computes the optimal reservation productivity -that he calls recruitment standard- for a fixed wage. He also shows that if the firms had very flexible wages, they would use that tool rather than a recruitment standard, but we do not consider that firms can change their wage offer to respond to their idiosyncratic recruiting problems.

Internal candidates are employees of the firm with a seniority greater than a certain threshold (SeniorityThreshold), and whose occupation is strictly one level lower to the occupation level of the job.

The amenity is a proxy for all the factors that make the work pleasant or painful. We consider the work time per period when we calculate this amenity to avoid a bias, and above all, the amenity is fully revealed to the employee only after hiring. This amenity discovery could cause some early quitting, as it is happening in reality. Thus, in terms of imperfect information, there is a symmetric process between amenity discovery for the employee and employee’s productivity discovery for the employer. The main difference is that we assume the employee to be promptly informed of the amenity, while the productivity is measured only very gradually (the probationary period is too short to reveal the real productivity).

In fact, and even if societies are constantly evolving on that issue. French women in 2011 have devoted more time than men to housework and the education of children. According to INSEE’s enquiry on time use (2010), on average (including persons withot children), women devote 45mn daily to care for children, while men spend only 19 mn on such an activity. Indeed, in 2011, the employment rate of French women working full-time and living in a couple with three children or more was 39.8 % against 87 % for men in the same situation (INSEE 2011b).

However, for states perceived as temporary, such as unemployment, the individual takes into account in the utility of this state the expectation of a future job. See below.

As for “Revenu de solidarité active”. In France, this a minimum income for people without resources. In 2011, the RSA was 467 € per month for a single person aged 25 or more.

We distinguish this myopic utility to be unemployed \(\textit{UTUEM}_{i,t}\) from the dynamic reservation utility \(\textit{UTRES}{}_{i,t}\) according to search theory that takes into account the expectation to get a job with an expected salary. This dynamic reservation utility remains based on bounded rationality, since searchers do not anticipate the possible breach of the contract they look for, and the values of the many states beyond.

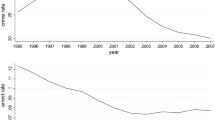

These targets could not be found for later than 2007. However. these transitions are not too volatile. even the partial information we have obtained for 2011 displays the effects of the crisis—see Table 2.

According to Berche et al. (2011), in 2010, 46.2 % of total hires are for FDC one week or less, and 18 % less than one month (statistics based on the DUE).

Gradin et al. (2015) show that 20 % of unemployment spells in Spain last less than one month in 2007, a fact easy to explain by the weight of FDC in this country.

In this paragraph, we rounded the flow numbers given by WorkSim to ease the reading and comparisons.

We could multiply the flow by 52 to obtain an annual flow. We do not since the numbers in the text would differ from those in the figure, which would be confusing. However, one can see that for the hires in FDC, it would yield a figure of 8.4 millions. This is half the number of FDC hires in the DUE. The simulated annual hires into OEC amount to 2.6 millions, to compare with the 3.4 millions in DUE. We underestimate because the model is calibrated on the DMMO that underestimate gross flows into short FDC, but the bias is slight compared to the bias in flows measured on a monthly transition matrix.

This distinction would call for developments for which we do not have space in this paper, as well as an extensive explanation of the results. See Ballot (2002, p.72). who distinguishes static and dynamic segmentation.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Pischke, J.-S. (1999). The structure of wages and investment in general training. Journal of Political Economy, 107, 539–572.

Adams, J. S. (1963). Towards an understanding of inequity. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(5), 422.

Arrow, K. J. (1962). The economic implications of learning by doing. The Review of Economic Studies, 29(3), 155–173.

Auger, A. & Hansen, N. (2012). Addressing numerical black-box optimization: CMAE-ES. LION 6, 16-20 January 2012, Paris, France.

Ballot, G. (1981). Marché du travail et dynamique de la répartition des revenus salariaux. Thèse pour le doctorat d’Etat d’Economie, Université Paris X-Nanterre.

Ballot, G. (1988). Concurrence entre catégories de main-d’Oeuvre et fonctionnement du marché du travail: l’expérience du modèle ARTEMIS. In Ministère d’Etat chargé du Plan et de l’Aménagement du Territoire et Ministère du Travail, de l’Emploi et de la Formation professionnelle, Structures du marché de travail et politiques (pp. 224–240). Paris: Syros.

Ballot, G. (2002). Modeling the labor market as an evolving institution: Model artemis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 49(1), 51–77.

Ballot, G., & Taymaz, E. (1997). The dynamics of firms in a micro-to-macro model: The role of training, learning and innovation. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 7(4), 435–457.

Ballot, G. & Taymaz, E. (2000). Competition, training, heterogeneity persistence, and aggregate growth in a multi-agent evolutionary model. In G. Ballot & G. Weisbuch (Eds.) Applications of Simulation to Social Sciences Oxford: HERMES Science.

Barlet, M., Blanchet, D., & Le Barbanchon, T. (2009). Microsimulation et modèles d’agents; une approche alternative pour l’évaluation des politiques d’emploi. Economie et Statistique, 429–430, 51–76

Barlet, M., Minni , C.and Ettouati, S., Finot, J., & Paraire, X. (2014). Entre 2000 et 2012, forte hausse des embauches en contrats temporaires, mais stabilisation de la part des cdi dans l’emploi. DARES Analyses 56. Paris: DARES.

Becker, G.S. (1975). Investment in human capital: Effects on earnings. In Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (2nd ed., pp. 13–44). New York: NBER

Beffy, M., Buchinsky, M., Fougère, D., Kamionka, T., & F., Kramarz. (2006). The returns to seniority in France (and why they are lower than in the US?). IZA DP 1935, PP. 155–173.

Berche, K., Hagneré, C., & Vong, M. (2011). Les déclarations d’embauche entre 2000 et 2010 : une évolution marquée par la progression des CDD de moins d’un mois. Acoss Stat, (143), Décembre 2011.

Berche, K. & Vong, M. (2012). La baisse des embauches de plus d’un mois se confirme au premier trimestre 2012. ACCOSTAT, (149)

Bergmann, B. (1974). A microsimulation of the macroeconomy with explicitely represented money flows. Annals of Economic and Social Measurement, 3, 475–489.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (1994). The wage curve. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Conseil d’Orientation pour l’Emploi (COE). (2013). Emplois durablement vacants et difficultés de recrutement. Rapport technique.

DARES. (2012). Les mouvements de main-d’oeuvre en 2011. DARES Analyses, (71).

Deroyon, T., Montaut, A., & Pionnier, P.-A. (2013). Utilisation rétrospective de l’enquête emploi à une fréquence mensuelle : apport d’une modélisation espace-état. Document de travail, g2013/01-f1301, INSEE.

Dubois, Y., Hairault, J.-O., Le Barbanchon, T., Sopraseuth, T., et al. (2011). Flux de travailleurs au cours du cycle conjoncturel. Paris: Université Paris 1.

Eliasson, G. (1977). Competition and market processes in a simulation model of the Swedish economy. American Economic Review, 67(1), 277–281

Gibbons, R., Katz, L. F., Lemieux, T., & Parent, D. (2005). Comparative advantage, learning, and sectoral wage determination. Journal of Labor Economics, 23(4), 681–724.

Gradín, C., Cantó, O., & del Río, C. (2015). Unemployment and spell duration during the great recession in the EU. International Journal of Manpower, 36(2), 216–235.

Hansen, N., & Ostermeier, A. (2001). Completely derandomized self-adaptation in evolution strategies. Evolutionary Computation, 9(2), 159–195.

INSEE. (2008). Population active à la recherche d’un autre emploi (PARAE). (87).

INSEE. (2011a). Entreprises selon le nombre de salariés et l’activité en 2011.

INSEE. (2011b). Taux d’activité selon le sexe et la configuration familiale en 2011.

INSEE. (2011c). Taux de chômage par âge en 2011.

INSEE. (2011d). Une photographie du marché du travail en 2011.

INSEE. (2013a). Fiches thématiques - Synthèse des actifs occupés - Emploi et salaires - Insee Références - Édition 2013.

INSEE. (2013b). L’emploi dans la fonction publique en 2011. Insee Premiére (1460).

INSEE. (2014). Table insee natnon03324. Rapport technique.

Jauneau, Y. & Nouel de Buzonniere, C. (2011). Transitions annuelles au sens du BIT sur le marché du travail. INSEE.

Jovanovic, B. (1979). Job matching and the theory of turnover. The Journal of Political Economy, 87(5), 972–990.

Kambourov, G., & Manovskii, I. (2009). Occupational specificity of human capital. International Economic Review, 50(1), 63–115.

Leiponen, A. (2005). Skills and innovation. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 23(5), 303–323.

Lewkovicz, Z., & Kant, J.-D. (2008). A multi-agent simulation of a stylized french labor market : Emergences at the micro-level. Advances in Complex Systems, 11(2), 217–230.

Lindbeck, A., & Snower, D. J. (1988). The insider-outsider theory of employment and unemployment. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Mortensen, D. T., & Pissarides, C. (1994). Job creation and job destruction in the theory of unemployment. Review of Economic Studies, 61(3), 397–415.

Neugart, M. (2008). Labor market policy evaluation with ACE. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 67(2), 418–430.

OECD. (2011). Oecd economic outlook (Vol. 2011(1)). Rapport Technique. Paris: OECD.

Omicini, A., Ricci, A., & Viroli, M. (2008). Artifacts in the A&A meta-model for multi-agent systems. Autonomous Agents and Multi-Agent Systems, 17(3), 432–456.

Phelps, E. (1970). Microfoundations of employment and inflation theory. London: Macmillan.

Pissarides, C. (1976). Labour market adjustment: Microeconomic foundations of short-run Neoclassical and Keynesian dynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pissarides, C. (1990). Equilibrium unemployment theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

Pissarides, C. (2009). The unemployment volatility puzzle: Is wage stickiness the answer. Econometrica, 77(5), 1339–1369.

Richiardi, M. (2006). Toward a non-equilibrium unemployment theory. Computational Economics, 27, 135–160.

Salop, S. C. (1979). Monopolistic competition with outside goods. The Bell Journal of Economics, 10(1), 141–156.

Service-Public.fr. (2011). Allocation d’aide au retour à l’emploi (ARE) : montant et versement.

Simon, H. A. (1955). A behavioral model of rational choice. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69(1), 99–118.

Simon, H. A. (1956). Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review, 63(2), 129–138.

Stigler, G. J. (1962). Information in the labor market. The Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 94–105.

Tassier, T., & Menczer, F. (2001). Emerging small-world referral networks in evolutionary labor markets. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, 5(5), 482–492.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: List of WorkSim Agents Characteristics

Appendix 2: Parameters of the Institutional Framework

Parameter | Description | Value for France in 2011 |

|---|---|---|

FDCbonus | Percentage of the gross wage given to the employee at the end of a FDC if not converted in an OEC | 10 % |

FiringCost | Firing cost of an employee in OEC depending on his/her salary and seniority | cf. paragraph below |

NoticePeriodOEC | Legal dismissal advance notice period for an OEC | 1 month if employees’ seniority is below 2 years. 2 months otherwise. |

EmployerCharges | Percentage of employer’s social security contributions on net wage | 54 % |

EmployeeCharges | Percentage of employee’s social security contributions on net wage | 28 % |

\(ReductionCharges_>20\) | Reduction of employer’s charges at the SMIC level for firms with 20 employees or more | 26 % of gross wage |

\(ReductionCharges_<20\) | Reduction of employer’s charges at the SMIC level for firms with less than 20 employees | 28.1 % of gross wage |

SMIC | Monthly net minimum wage for a full-time job | 1 072 € |

RSA | Minimum income for people without ressources | 467 € per month for a single person aged 25 or more |

ALCHO | Unemployment benefits | See Service-Public.fr (2011) for the calculation |

ProbationaryPeriodFDC | Probationary period of a FDC | One day per working week with a limit of 2 weeks if the expected duration of the contract is below 6 months. 1 month if the expected duration of the contract is over 6 months. |

ProbationaryPeriodOEC | Probationary period of a OEC | 2 months for blue collars. 3 months for middle level positions. 4 months for executives. |

WorktimePerPeriod | Legal work time per week for a full time job | 35 hours |

AgeRetirement | Minimum retirement age for a full-rate pension | 65 years |

1.1 Firing Costs in France in 2011

In 2011, according to the article R. 1234-2 of the Labor Code in France in 2011, the severance pay for an employee dismissed is one fifth of one month’s salary per year of seniority. For an employee with at least ten years of seniority, this severance pay is one fifth of one month’s salary plus two fifteenth of one month’s salary per year of seniority over ten years (According to the Labor laws L.1234-9, R.1234-2 and R.1234-4). The reference salary used to calculate the severance pay is the maximum between the average of the gross wages in the last 12 months and the average of the gross wages in the last 3 months.

Appendix 3: Calibration Results

Appendix 4: Calibrated Exogenous Parameters of the Model

Parameter | Description | Calibrated value |

|---|---|---|

\(\alpha _{0}\) | Average base factor for individual preference for free time | 0.188 |

\(\alpha _{old}\) | Increment of the factor for individual preference | 0.038 |

for free time every year for an individual | ||

\(\alpha _{child1}\) | First sensitivity parameter to the preference for free time of women depending on the number of children in her household | 0.47 |

\(\alpha _{child2}\) | Second sensitivity parameter to the preference for free time of women depending on the number of children in her household | 1.29 |

\(\alpha _{youngWomen}\) | Specific sensitivity parameter to the preference for free time for young women under 25 having children | 2.7 |

\(\textit{ICHANG}\) | Psychological cost of starting to search for a job | 1.21 |

ProfitThreshold | Profit threshold under which the firm initiates a redundancy plan | −4.5 % |

\(\sigma _{D}\) | Demand volatility of each firm | 0.0139 |

PrLossXP | Percentage of general experience loss each period after 6 month out of employment | \(0.018~\%\) |

UtilityContract | Base parameter for calculation of preference for contract stability | 7.3 |

sensiStabAge | Sensitivity factor to age in the preference for contract stability | 0.0002 |

\(N_{1}\) | Parameter in hiring norm calculation | 0.50 |

\(N_{3}\) | Parameter in hiring norm calculation | 0.049 |

\(N_{4}\) | Parameter in hiring norm calculation | 0.0099 |

\(ParamUTRES_{1}\) | Parameter in reservation utility calculation | 1.69 |

\(ParamUTRES_{3}\) | Parameter in reservation utility calculation | 0.001 |

\(\zeta \) | Share of sales revenue kept by the firm | 0.749 |

P | Price of the good in the economy | 0.79 |

\(\Psi _{Executive}\) | Mean share of the firm demand allocated to executive positions | 0.48 |

\(\Psi _{MiddleLevel}\) | Mean share of the firm demand allocated to middle level positions | 0.33 |

\(\beta _{Excecutive}\) | Increase factor of human capital with experience for executive jobs | 0.001 |

\(\beta _{MiddleLevel}\) | Increase factor of human capital with experience for middle level jobs | 0.001 |

\(\beta _{EO}\) | Increase factor of human capital with experience for employee/worker jobs | 0.0005 |

\(\sigma _{CProd}\) | Standard deviation of the distribution of individual productivity core | 0.38 |

\(\sigma _{0}\) | Initial standard deviation of employee productivity estimation by firms | 0.43 |

\(probaFDC_{Executive}\) | Probability to draw a FDC contract when creating job for executives | 0.032 |

\(probaFDC_{MiddleLevel}\) | Probability to draw a FDC contract when creating job for middle level jobs | 0.585 |

\(probaFDC_{EO}\) | Probability to draw a FDC contract when creating job for employee/worker jobs | 0.97 |

\(Q_{Executive}^{base}\) | Average base productivity of executive jobs | 2301 |

\(Q_{MiddleLevel}^{base}\) | Average base productivity of middle level jobs | 1393 |

\(Q_{Employee/Workers}^{base}\) | Average base productivity of employee/worker jobs | 671 |

EmployThreshold | Employability threshold above which the individuals find themselves employable | 220 |

\(ProbaFDC_{1week}\) | Probability to draw duration of 1 week when creating a FDC contract | 0.59 |

\(ProbaFDC_{1month}\) | Probability to draw duration of 1 month when creating a FDC contract | 0.18 |

\(ProbaFDC_{2months}\) | Probability to draw duration of 2 months when creating a FDC contract | 0.091 |

\(ProbaFDC_{6months}\) | Probability to draw duration of 6 months when creating a FDC contract | 0.016 |

\(ProbaFDC_{12months}\) | Probability to draw duration of 12 months when creating a FDC contract | 0.12 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goudet, O., Kant, JD. & Ballot, G. WorkSim: A Calibrated Agent-Based Model of the Labor Market Accounting for Workers’ Stocks and Gross Flows. Comput Econ 50, 21–68 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-016-9577-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-016-9577-0