Abstract

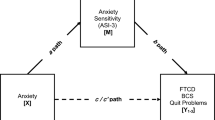

There is a growing literature that documents the direct and indirect effects of anxiety sensitivity in terms of the maintenance of cigarette smoking and cessation problems, as maintained, at least in part, by affective-regulatory expectancies effects and motives for smoking. Yet, the role of expectancies about the interoceptive-specific consequences of smoking abstinence has yet to be empirically examined. Participants (N = 110) were daily tobacco smokers recruited as part of a self-guided tobacco cessation study. Baseline (pre-treatment) data were utilized. A structural equation model was constructed to examine the relations between anxiety sensitivity in terms of interoceptively-relevant smoking abstinence expectancies (somatic symptoms and harmful consequences) in regard to perceived barriers to smoking cessation, number of problematic symptoms experienced during past quit attempts, and the number of prior quit attempts. Anxiety sensitivity was significantly related to interoceptive threat abstinence expectancies (β = .56, p < .001). Expectancies were directly related to perceived barriers to smoking cessation (β = .39, p < .001) and number of problematic symptoms experienced during past quit attempts (β = .41, p < .001), but not the number of prior quit attempts. Mediational results indicated indirect (but not direct) effects of anxiety sensitivity on perceived barriers to smoking cessation and problems during prior quit attempts; effects that occurred through interoceptive threat smoking abstinence expectancies. The present findings suggest that one’s expectancies about the negative interoceptive consequences of smoking abstinence may be an explanatory mechanism between anxiety sensitivity and certain quit-relevant smoking processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The current data were collected between 2010 and 2013, prior to the publication of the DSM-5; thus, anxiety disorders included the following: panic disorder with/without agoraphobia, agoraphobia, social phobia, specific phobias, obsessive–compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder.

References

Abrams, K., Zvolensky, M. J., Dorman, L., Gonzalez, A., & Mayer, M. (2011). Development and validation of the smoking abstinence expectancies questionnaire. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 13(12), 1296–1304. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr184.

Arbuckle, J. L. (2012). IBM ® SPSS ® Amos™ 21.0 user’s guide. Chicago, IL: IBM Corporation.

Assayag, Y., Bernstein, A., Zvolensky, M. J., Steeves, D., & Stewart, S. S. (2012). Nature and role of change in anxiety sensitivity during NRT-aided cognitive-behavioral smoking cessation treatment. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 41(1), 51–62. doi:10.1080/16506073.2011.632437.

Baker, T. B., Brandon, T. H., & Chassin, L. (2004a). Motivational influences on cigarette smoking. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 463–491. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142054.

Baker, T. B., Piper, M. E., McCarthy, D. E., Majeskie, M. R., & Fiore, M. C. (2004b). Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review, 111(1), 33–51. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33.

Brown, R. A., Kahler, C. W., Zvolensky, M. J., Lejuez, C. W., & Ramsey, S. E. (2001). Anxiety sensitivity: Relationship to negative affect smoking and smoking cessation in smokers with past major depressive disorder. Addictive Behaviors, 26(6), 887–899. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00241-6.

Brown, R. A., Lejuez, C. W., Kahler, C. W., & Strong, D. R. (2002). Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(1), 180–185. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.180.

Cox, W. M., & Klinger, E. (1988). A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(2), 168–180.

Farris, S. G., Vujanovic, A. A., Hogan, J., Schmidt, N. B., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2014). Main and interactive effects of anxiety sensitivity and physical distress intolerance with regard to PTSD symptoms among trauma-exposed smokers. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 15(3), 254–270. doi:10.1080/15299732.2013.834862.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. (2007). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCIDI/NP). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Gonzalez, A., Zvolensky, M. J., Hogan, J., McLeish, A. C., & Weibust, K. S. (2011). Anxiety sensitivity and pain-related anxiety in the prediction of fear responding to bodily sensations: A laboratory test. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 70(3), 258–266. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.07.011.

Heatherton, T. F., Kozlowski, L. T., Frecker, R. C., & Fagerström, K. (1991). The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x.

Hendricks, P. S., & Leventhal, A. M. (2013). Abstinence related expectancies predict smoking withdrawal effects: Implications for possible causal mechanisms. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 21(4), 269–276. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-3169-7.

Hendricks, P. S., Westmaas, J. L., Ta Park, V. M., Thorne, C. B., Wood, S. B., Baker, M. R., et al. (2013). Smoking abstinence-related expectancies among American Indians, African Americans, and Women: Potential mechanisms of disparities. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors,. doi:10.1037/a0031938.

Hendricks, P. S., Wood, S. B., Baker, M. R., Delucchi, K. L., & Hall, S. M. (2011). The smoking abstinence questionnaire: Measurement of smokers’ abstinence-related expectancies. Addiction, 106, 716–728. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03338.x.

Hopper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6, 53–60.

Johnson, K. A., Farris, S. G., Schmidt, N. B., Smits, J. A., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2013). Panic attack history and anxiety sensitivity in relation to cognitive-based smoking processes among treatment-seeking daily smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 15(1), 1–10. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr332.

Johnson, K. A., Stewart, S., Rosenfield, D., Steeves, D., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2012). Prospective evaluation of the effects of anxiety sensitivity and state anxiety in predicting acute nicotine withdrawal symptoms during smoking cessation. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 26(2), 289–297. doi:10.1037/a0024133.

Kassel, J. D., Stroud, L. R., & Paronis, C. A. (2003). Smoking, stress, and negative affect: correlation, causation, and context across stages of smoking. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 270–304. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.270.

Kelly, M. M., Grant, C., Cooper, S., & Cooney, J. L. (2013). Anxiety and smoking cessation outcomes in alcohol-dependent smokers. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 15(2), 364–375. doi:10.1093/ntr/nts132.

Kenny, D.A. (2014). Measuring Model Fit. Retrieved March 31, 2014, 2014, from http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Kraemer, K. M., Luberto, C. M., & McLeish, A. C. (2013). The moderating role of distress tolerance in the association between anxiety sensitivity physical concerns and panic and PTSD-related re-experiencing symptoms. Anxiety, Stress and Coping: An International Journal, 26(3), 330–342.

Leyro, T. M., Zvolensky, M. J., Vujanovic, A. A., & Bernstein, A. (2008). Anxiety sensitivity and smoking motives and outcome expectancies among adult daily smokers: replication and extension. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 10(6), 985–994. doi:10.1080/14622200802097555.

Macnee, C. L., & Talsma, A. (1995). Development and testing of the barriers to cessation scale. Nursing Research, 44(4), 214–219. doi:10.1097/00006199-199507000-00005.

Marshall, E. C., Johnson, K., Bergman, J., Gibson, L. E., & Zvolensky, M. J. (2009). Anxiety sensitivity and panic reactivity to bodily sensations: Relation to quit-day (acute) nicotine withdrawal symptom severity among daily smokers making a self-guided quit attempt. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17(5), 356.

Marshall, G. N., Miles, J. N., & Stewart, S. H. (2010). Anxiety sensitivity and PTSD symptom severity are reciprocally related: Evidence from a longitudinal study of physical trauma survivors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119(1), 143–150. doi:10.1037/a0018009.

McCarthy, D. E., Curtin, J. J., Piper, M. E., & Baker, T. B. (2010). Negative reinforcement: Possible clinical implications of an integrative model. In J. D. Kassel (Ed.), Substance absuse and emtoion (pp. 15–42). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

McNally, R. J. (2002). Anxiety sensitivity and panic disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 52(10), 938–946. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01475-0.

Perna, G., Romano, P., Caldirola, D., Cucchi, M., & Bellodi, L. (2003). Anxiety sensitivity and 35 % CO2 reactivity in patients with panic disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 54(6), 573–577. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00468-3.

Rapee, R. M., & Medoro, L. (1994). Fear of physical sensations and trait anxiety as mediators of the response to hyperventilation in nonclinical subjects. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103(4), 693.

Reiss, S., Peterson, R. A., Gursky, D. M., & McNally, R. J. (1986). Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24(1), 1–8. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9.

Schmidt, N. B., Zvolensky, M. J., & Maner, J. K. (2006). Anxiety sensitivity: Prospective prediction of panic attacks and axis I pathology. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40(8), 691–699. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.009.

Sirota, A. D., Rohsenow, D. J., Dolan, S. L., Martin, R. A., & Kahler, C. W. (2013). Intolerance for discomfort among smokers: Comparison of smoking-specific and non-specific measures to smoking history and patterns. Addictive Behaviors, 38(3), 1782–1787.

Taylor, S., Zvolensky, M. J., Cox, B. J., Deacon, B., Heimberg, R. G., Ledley, D. R., et al. (2007). Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the anxiety sensitivity index-3. Psychological Assessment, 19(2), 176–188. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176.

Tofighi, D., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2011). RMediation: An R package for mediation analyses confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 692–700.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Zvolensky, M. J., Baker, K. M., Leen-Feldner, E., Bonn-Miller, M. O., Feldner, M. T., & Brown, R. A. (2004). Anxiety sensitivity: Association with intensity of retrospectively-rated smoking-related withdrawal symptoms and motivation to quit. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 33(3), 114–125. doi:10.1080/16506070310016969.

Zvolensky, M. J., Bogiaizian, D., Salazar, P. L., Farris, S. G., & Bakhshaie, J. (2014a). An anxiety sensitivity reduction smoking cessation program for Spanish-speaking smokers. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 21, 350–363.

Zvolensky, M. J., Farris, S. G., Guillot, C. R., & Leventhal, A. M. (2014b). Anxiety sensitivity as an amplifier of the subjective and behavioral tobacco abstinence effects. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 142, 224–230.

Zvolensky, M. J., Farris, S. G., Schmidt, N. B., & Smits, J. A. (2014c). The role of smoking inflexibility/avoidance in the relation between anxiety sensitivity and tobacco use and beliefs among treatment-seeking smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22(3), 229–237. doi:10.1037/a0035306.

Zvolensky, M. J., Yartz, A. R., Gregor, K., Gonzalez, A., & Bernstein, A. (2008). Interoceptive exposure-based cessation intervention for smokers high in anxiety sensitivity: A case series. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 22(4), 346–365. doi:10.1891/0889-8391.22.4.346.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a pre-doctoral National Research Service Award from the National Institute of Drug Abuse awarded to Dr. Langdon (F31-DA026634). Ms. Farris acknowledges support from a pre-doctoral National Research Service Award from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (F31-DA035564). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government, and the funding sources had no other role than financial support.

Conflict of Interest

Samantha G. Farris, Kirsten J. Langdon, Angelo M. DiBello, and Michael J. Zvolensky declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Houston and the University of Vermont. Informed consent was obtained from all individual subjects participating in the study.

Animal Rights

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Farris, S.G., Langdon, K.J., DiBello, A.M. et al. Why Do Anxiety Sensitive Smokers Perceive Quitting as Difficult? The Role of Expecting “Interoceptive Threat” During Acute Abstinence. Cogn Ther Res 39, 236–244 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9644-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-014-9644-6