Abstract

In the area of financial services, lawmakers and regulators increasingly promote the use of plain language in business-to-consumer contracts. Although such efforts are undoubtedly welcomed by consumers, as they promote better comprehension, not much is known about the actual effects of improved readability on consumer attitudes and cognitive processes. Does improved readability in general contract terms have an impact on the consumer’s perception of their contractual position? Do contracts that are easier to read influence the steps or actions taken by consumers in the wake of conflict? In response to these questions, we present data from an experiment that investigates the relationship between the reading ease of general contract terms on the one hand and consumer expectations and willingness to engage in conflict on the other. Our findings suggest that readability increases the trust and confidence of the consumer in the sense that it increases their expectations of the claim. Moreover, we have found partial evidence to suggest that reading ease also increases the consumer’s willingness to engage in legal action in the case of subsequent claim denial.

Similar content being viewed by others

In recent years, the interest in the readability of business communication has grown considerably. The financial services industry—an industry that designs and sells products, which are intangible and consist entirely of words—is a case in point. Against the backdrop of diminishing levels of consumer trust in financial institutions, such as banks and insurance companies, several initiatives have recently been deployed in the financial services arena aimed at garnering consumer trust by “simplification” of legal written material for instance, contracts, standard contract terms, disclaimers, and correspondence. Indeed, conventional wisdom is that simple words and sentences are highly valued by consumers whilst “legalese” and legal “mumbo jumbo” make them suspicious. (Office of Fair Trading (OFT) 2011). Moreover, there is ample evidence to show that consumers lack the motivation to read general contract terms in the first place and that they quite easily suffer from information overload and cognitive depletion if they actually do. (Becher and Unger-Aviram 2010; Hillman 2006; Luth 2010; OFT 2011; Pogrund Stark and Choplin 2009). It comes as no surprise therefore that the policy goal of improving readability of legal documentation has found its way into regulatory agendas. Various EU rules and national rules instruct financial service providers to communicate in a clear, fair and non-misleading way.Footnote 1 Moreover, Article 5 of the EU Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Directive (93/13/EEC) simply stipulates that general contract terms shall be drafted in plain, intelligible language and that, in the case of ambiguity, the interpretation most favourable to the consumer prevails. Recently, in its preliminary rulings in the Kásler and Van Hove cases, the ECJ has reinforced its consumer-orientated approach in the application of Directive 93/13/EEC by specifying that contract terms require not only to be grammatically intelligible but also that the contract sets out the specific contractual mechanisms transparently in order that the consumer is in a position to evaluate the economic consequences which ensue from the contract (ECJ April 30, 2014, case C-26/13 (Kásler en Rábai / OTP Jelzálogbank Zrt); ECJ April 23, 2015, case C-96/14 (Van Hove / CNP Assurances SA)).

Hence, it seems that lawmakers, regulators, and courts alike are keen to support the “plain language movement” by striving for simplicity in legal documents. Indeed, at first glance, there is much to be said in favour of the “plain language movement.” Research, for instance, shows that plain language, consistent use of vocabulary, avoidance of overload and ambiguity, adaptation to the readership, and ease of document structure may impact on comprehension (Campbell 1999; Davis 1977; Garrisson et al. 2012; Greene et al. 2012; Kieras and Dechert 1985; Campbell 1999). Furthermore, the use of headers may aid recall and retrieval tasks (Hartley and Trueman 1983) and that adding connectors, logical structures, and coherence markers between sentences are beneficial to inexperienced readers (Kamalski et al. 2006). Likewise, in the area of legal communication, there is evidence to show that simplification of legal documents improves clarity for non-expert readership. (Adler 2012; Davis 1977; Hiltunen 2012; Masson and Waldron 1994; Pander Maat et al. 2009). For example, Charrow and Charrow (1979) asked lay jurors to paraphrase the jury instructions read out to them and it was observed that “easier” instructions resulted in a considerable improvement in performance. Tiersma and Curtis (2008) tested the comprehensibility of old and new versions of the Californian jury instructions on judgements of “circumstantial” versus “direct evidence.” The new instructions, in contrast to the old ones, contained more ordinary phrasing and included examples and illustrations. The authors observed that participants who received the new, easier version were more often correct in their judgement than participants who were given the old version (Tiersma and Curtis 2008).

In light of this literature, it seems reasonable to assume that simplifying language merely has beneficial effects and that improvement in ease of reading automatically accommodates consumer needs (Adler 2012). Indeed, when asked, consumers state that they value attempts to simplify wording and structure of general contract terms and that they prefer simplicity to “legalese” (OFT 2011; Treur and van Rijckevorsel 2004). The question however remains: What effect does improved reading ease actually have on consumers? Looking at the literature on reading ease, it is clear that although considerable effort has been put into measuring and improving readability, research into its behavioural effects is scarce. In fact, there is hardly any research that goes beyond issues such as comprehension, retention, and accessibility of text structure. For instance, what do we know about the effects of improved readability on both consumer attitudes and their “thinking and deciding” processes? Do consumers develop different attitudes towards the user of the general contract terms? Are they more likely to develop trust in the user of the “easy to read” contract terms? Do they show more confidence in their own interpretation of the contract, given that they have a better understanding of the wording of the contract? Do they think and act differently when confronted with “easy to read” contact terms compared to consumers who are exposed to “legalese?”

We know precious little about whether “easy to read contracts” actually cause consumers to change their attitude towards the contract and the party who drafted the contract terms in question. The available evidence is at best, ambiguous. For instance, some research suggests that improved readability of written communication garners trust and confidence in consumers by reducing the number of customers seeking after-sales clarification of terms and instructions (Baker 2011). Other research attempted but failed to find a clear relationship between ease of reading and perceived fairness of a contract (Stolle 1998) or trust (Pan and Zinkhan 2006). Therefore, there is a need to look beyond comprehension and accessibility if lawmakers, regulators, and courts want to gauge the practical impact of their interventions.

Therefore, with this article we attempt to add to the literature on this matter. To be precise, we aim to answer how readability of general contract terms impacts on the consumer’s perceptions of their contractual position and their actions in the case of a conflict at the performance stage. To this end, we report an experimental study that focuses on one specific aspect of the effect of readability on both consumer attitudes and their thinking and deciding processes, namely in a situation of conflict at the stage of performance of the contract. The reason for focusing on the role of readability at the performance and conflict stage in a contractual relationship is for the external validity of our findings. As mentioned, the evidence shows that consumers lack motivation to read general contract terms prior to entering into a contract. However, if we assume in line with the existing literature (Pogrund Stark and Choplin 2009) that actually, the willingness to read is more likely to be present in the case of a conflict between a consumer and a business which uses general contract terms; it may be worthwhile to focus on exactly this stage in the life of a contract. Thus, we do not focus here on the stage of entry into a contract but merely on the role of reading ease at the performance and conflict stage in a contractual relationship.

The setup of this article is as follows. Firstly, we review the literature on the relationship between readability on the one hand and consumer attitudes and decision-making on the other. From this literature, we derive our hypotheses and introduce the design for our experiment which measures the relationship between readability of general contract terms, consumer trust, expectations, and willingness to engage in conflict. We conclude with a discussion of our findings and their implications.

Readability, Expectations, and Conflict Behaviour

There are good reasons to believe that readability of contracts may indeed exert a positive influence on consumer attitudes towards the contracting party. For instance, the literature on “processing fluency” may be of relevance. This strand of research into the ease (“fluency”) or difficulty (“disfluency”) experienced in processing information consistently found that stimuli that are more easily processed are in general also evaluated more positively (Reber et al. 1998; Reber et al. 2004) and even increase the activation of zygomaticus major, the muscle involved in smiling (Winkielman and Cacioppo 2001). Moreover, research has also revealed that more processing fluency is also associated with perceiving products as less risky. Song and Schwarz (2009), for example, observed that food additives with names that are easier to pronounce are also seen as less risky products. Likewise, Alter and Oppenheimer (2006) observed that people attribute higher performance to fictional stocks that have easier names. In short, the research on “processing fluency” shows that “processing fluency” serves as a proximal cue which is integrated into cognitive assessments and evaluations (Alter and Oppenheimer 2009; Schwarz 2004).

Building on the insight that product features which are easily processed are evaluated more positively, are seen as less risky, and are more effective; it stands to reason that contracts that are easier to read may also elicit more positive evaluations and trust of consumers towards the product itself. At the same time however, the fact that consumers may perceive their contract more positively, creates another consequence for parties issuing more readable contracts and that is, that consumer expectations are raised. This rise may be attributed to the concept of trust. According to the most widely used definitions, trust constitutes a willingness to be vulnerable that is based on expectations of particular behaviour (Mayer et al. 1995; Rousseau et al. 1998). Therefore by definition, trust only exists to the extent that parties expect trustworthy behaviour. If someone has more trust towards another party, he or she also expects to a greater extent that this trust will be honoured. For example, in the case of general insurance contract terms, this would mean that consumers exposed to “easy to read contracts” develop higher expectations of the other party to the contract at the performance stage that is at the stage of submission of a claim allegedly covered under the policy. Consumers may thus hold inflated beliefs about their actual contractual position and, in the case of insurance contracts, expect their insurance and the coverage of the contract to be more beneficial. This leads us to our first testable hypothesis, namely, that improving reading ease in general contract terms increases consumer expectations at the performance stage.

With these inflated expectations, however, there may also be a caveat for parties who make use of general contract terms. Trust in contractual relations does not typically amount to a robust and less calculative form of trust that is based on repeatedly consistent, positive interaction. Trust in these relations is more outcome-based and therefore more vulnerable to deterioration when conflict arises (Lewicki and Bunker 1995, 1996). In other words, actors in these relations may trust but will always verify whether their expectations are met (Lewicki and Bunker 1995, 1996; Lewicki et al. 2006; Rousseau et al. 1998). As a result, whereas “easy to read” contract terms may increase trust, the inherent increased expectations will also be the measuring rod for consumers when deciding to take action (i.e., filing a complaint or undertaking legal action) if these expectations are not met. This results in a second testable hypothesis, namely, that the higher the claim expectation, the greater the willingness to engage in conflict when the other party to the contract does not meet these augmented expectations.

Taking the existing literature further, we have therefore, postulated two hypotheses. Now a third is added to test the combined effect of the first two, namely, that a direct relationship exists between ease of reading and conflict attitude:

-

1.

Improvement of readability increases claim expectations.

-

2.

Higher claim expectations are associated with a greater willingness to engage in conflict when the claim is refused.

-

3.

Readability increases the willingness to engage in conflict.

The Experiment

Method

Recently, a number of Dutch insurance companies changed their general insurance terms in so far as these relate to car insurance. This was done in order to improve readability and increase public trust in their products. This allowed us to take the new and old version of the terms (“difficult” vs. “easy”) from one of the insurance companies as a case in point and to test our hypotheses on actual policy terms.

Participants and Design

A representative sample of 1542 Dutch citizens (52% female) participated in our online study. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions of our experimental between-subjects design. Participants were on average 51.94 years old (SD = 13.87), were all in the possession of a driving licence and had been holding that licence for an average of 29.77 years (SD = 14.17 years). Of the participants, 3% had completed elementary school only, 21% finished secondary school, 37% completed post-secondary vocational college (MBO), 29% went through post-secondary senior vocational college (HBO), and 11% had a university degree.

Procedure

Participants were informed that the study was not a test of legal knowledge and that they should follow their own judgement. The participants were then provided with a scenario describing a car accident they were involved in. They were driving the vehicle at the time of the accident. The accident in the scenario concerned a collision at a roundabout involving two motor vehicles. It occurred during the winter. The participants were told that they had been driving within the speed limit and that as they approached the roundabout and reduced their speed accordingly, an ice patch caused them to skid and collide with another vehicle.

The participants were told that due to the collision, the other vehicle was damaged but was able to be repaired and that although they themselves were not injured, the driver of the other vehicle sustained some minor injuries, namely bruising. Finally, the participants were informed that the other driver claimed compensation. Then, the participants were then instructed to check their insurance contract for coverage. They were also asked to assess what part of the damage they thought would be covered by their insurance. As reported hereafter, the second part of the scenario involved a letter of refusal from the insurance company.

Depending on the condition to which they were assigned, the participants received one of two sets general contract terms (“difficult” and “easy”). The difference between the two sets was not substantive but merely linguistic, so that the sole manipulation was in the reading ease of the contract terms.

Obviously, a reliable and valid method of gauging the difference between the two versions of the general contract terms was needed. The methodology of measurement of readability constitutes a whole branch of (psycho-)linguistics in itself which we leave undiscussed, suffice to say that, there are numerous models and practical tests concerning reading ease of written communications and the level of proficiency and fluency of individuals. In Europe, a well-known expert scale for gauging individuals’ foreign language abilities is the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR). Other, often purely quantitative methods used for modelling reading ease tend to be less comprehensive but more reliable (Van Dam et al. 2012; Van Boom 2014). For instance, the Flesch Reading Ease scale is a basic quantitative score of reading ease between 0 (“illegible”) and 100 (“easy”) which consists of a weighted measurement of sentence length and number of syllables per word. Each of these competing models of reading ease measurement (and there are many more) has its deficiencies. Therefore, the combined use of different methods may induce a richer understanding of the true readability of written communication. In our experiment, we did exactly that and relied on a combination of the methods above.

In our stylized version, the “difficult” contract terms consisted of some 1940 words. The reading ease was at CEFR level C1 and scored 47.61 out of 120 on the Dutch Flesch-Douma Reading Ease scale (0–120). The “easy” version consisted of some 2580 words, was at CEFR level B1 (the level recommended in the Dutch insurance industry as fitting for consumer contract terms) and scored 61.18 out of 120 on the FDRE scale. Obviously, the sets were stylised to make them as comparable as possible: indices were removed; document structure, headings, font (Calibri, 11 point in a non-searchable pdf), and typesetting were identical. Note that the numerical difference in readability between the “hard” and “easy” version is relatively minor.

To ensure adequate external validity, participants were provided with the complete set of contract terms rather than with a single term or selection of terms. At all times during the experiment, the participants could consult the terms. Thus, with our design, we only varied language, not content, structure, headers, margins or fonts. Why did we expose readers to the entire set of contract terms? Research on the reading ease of legal documents tends to expose test participants to excerpts rather than a document in its entirety. The drawback of this, however, lies in the reduced external validity of the observations. The exposure of the participants to short excerpts does not provide evidence on whether any possible effect of reading ease will persist in real-life settings where complete contracts have to be processed. Given our aim to conduct applied research, we chose the more externally valid approach by providing the full set of contract terms and selecting a large, representative sample of the Dutch population.

To investigate how reading ease and expectations subsequently impact on conflict behaviour when the consumer’s expectations are not met, we provided a second follow-up scenario. Here, following the skidding accident, the insurance company was said to have sent the participants a letter of refusal (same for both versions, score of 71.16 on the FDRE scale). The letter of refusal stated that the insurance company had investigated the accident, that it had concluded that the insured had neglected to take nocturnal frost conditions into account, and that the accident had therefore been caused by “reckless driving,” which is explicitly excluded from coverage. In the letter, the insurer announced that it would recoup from the insured any payments made to the injured party. Importantly, both versions of the insurance contract terms identically excluded coverage for “reckless driving” without defining or illustrating it. Thus, our scenario was deliberately formulated as a situation for which there was no clear answer available in the terms regarding the compensation to be expected. By choosing this ambiguous case, the potential effects on the consumers’ perceived contractual position could only be explained by the variation in reading ease and not by a better understanding of the terms.

So, the participants were confronted with a refusal of coverage and therefore a potential conflict with the insurer. They were asked to what extent they agreed with the insurance company’s position. They were reminded again that they could consult the terms, bearing in mind, however, that the contract terms themselves do not provide any answer as to who is right and that the reader needs to interpret the policy exclusion. The participants were finally asked to what extent they were willing to engage in further conflict with the insurance company (e.g., by seeking advice, hiring a lawyer etc.)

Measures

Self-Reported Comprehension

After the participants had read the scenario, as a subjective test of readability, we firstly measured the extent to which participants found the contracts easy or difficult to understand using 4 items (all on seven-point Likert scales ranging from 1 = completely disagree to 7 = completely agree). The items were “The text contains a lot of difficult sentences” (reverse scored), “the text contains a lot of difficult words” (reverse scored), “the language in this text is difficult” (reverse scored), and “I found the text easy to understand.” Scores on these items correlated sufficiently and were combined in single seven-point Likert scale measuring self-reported comprehension (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Claim Expectation

We subsequently assessed the participants’ trust towards the insurer in terms of their claim expectation. More specifically, we asked them what part of the damage they thought would be compensated by their insurance company on a five-point Likert scale (1 = nothing, 2 = less than half, 3 = half, 4 = more than half, 5 = everything).

Conflict Behaviour

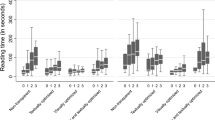

After the participants filled out the compensation estimate, we assessed their behavioural intentions in the second part of the scenario. We measured three types of post-conflict behaviour that clearly differ in so far as cost is concerned. We distinguished between: (1) information seeking (2) complaint filing, and (3) undertaking legal action. Three items were measured for information seeking firstly, asking for more information from the insurer; secondly, asking advice from family or friends and lastly, asking advice from an insurance expert, Cronbach’s α = .57). Two items assessed whether they would file a complaint with the insurance company or with the consumer complaint board (α = .63). The willingness to undertake legal action was measured using three items: going to court themselves; hiring a legal expert, but not a lawyer; and hiring a lawyer, even though the costs were likely to exceed the potential gain (α = .75).

Results

Self-reported Comprehension

Initially, to test whether the two contract versions resulted in different levels of perceived comprehension, we conducted a one-way anova with contract version as independent and the comprehension scale as dependent variable. The results clearly confirmed that participants who received the “easy” version found it easier to understand (M = 4.88, SD = 1.41) than participants who received the difficult version (M = 4.45, SD = 1.49), F(1, 1540) = 32.87, p < .001, η 2 = .02).

Claim Expectation

In order to evaluate the first hypothesis that reading ease increases the consumer’s expectations concerning their position vis-à-vis the other contracting party, a one-way anova was conducted with contract version as independent and claim expectation as dependent variable. The results supported our first hypothesis: Participants who received the “easy” version expected a larger part of the damage to be compensated (M = 4.67, SD = 0.88) than participants who received the difficult version (M = 4.53, SD = 0.98, F(1, 1540) = 8.98, p < .005, η 2 = .01).

Conflict Behaviour

Hypothesis two predicted that claim expectation was associated with the consumer’s behaviour in the event of an unsuccessful claim. More precisely, we anticipated those consumers who expect damage to be covered to a greater extent to also engage more in information seeking, complaint filing, or undertaking legal action.

An ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with claim expectation (standardized z-scores) predicting information seeking, yielded a significant main effect of claim expectation, indicating that the more participants expected the insurer to cover the damage, the more they were inclined to seek information from the insurer, family and friends, and other people with insurance expertise, b = 0.11, SE = 0.02, F(1, 1540) = 31.20, p < .001, η 2 = .02.

Likewise, the OLS regression with claim expectation (standardized z-scores) predicting complaint filing revealed a significant main effect of claim expectation, indicating that the more damage participants expected the insurer to cover, the more they were inclined to file a complaint to the insurer or to the ADR Board, b = 0.19, SE = 0.02, F(1, 1540) = 71.08, p < .001, η 2 = .04.

Finally, another OLS regression with claim expectation (standardized) predicting the consumer’s willingness to undertake legal action also resulted in a significant main effect of claim expectation. Participants who expected the insurer to cover more damage, were also more inclined to engage in legal action, by means of hiring a legal expert, going to court themselves, or instructing a solicitor to represent them in court, b = 0.11, SE = 0.02, F(1, 1540) = 20.90, p < .001, η 2 = .01. Hypothesis two was therefore confirmed.

Hypothesis three predicted a direct effect of reading ease on conflict behaviour. To evaluate this hypothesis, we used one-way anova’s to see whether the contract version had a direct effect on any of the three conflict behaviours. These analyses failed to show a direct effect of readability on information seeking, F(1, 1540) = 0.01, ns, complaint filing, F(1, 1540) = 0.26, ns, or the undertaking of legal action, F(1, 1540) = 0.89, ns. Hypothesis three was therefore not confirmed.

Discussion and Conclusion

In order to gain a better understanding of the influence of reading ease on consumer decision-making processes concerning contract clauses, the central question of our research was how reading ease in general contract terms impacts on the consumer’s perceptions of their contractual position and their actions in the case of a conflict at the performance stage. Our findings show that easier-to-read insurance contract terms inflate estimates of the compensation that will be awarded in the case of an accident. Secondly, we investigated whether readability also influences the willingness to engage in conflict in the case of unsuccessful claims. We measured the participant’s willingness to engage in advice seeking, complaint filing, or legal action and found evidence for an indirect relationship: Improved reading ease raised expectations of coverage which in turn was an important determinant of the willingness to seek information, file complaints, or undertake legal action. However, contrary to our expectations, we did not find a direct effect of reading ease on this willingness to engage in conflict. One of the explanations for this may be that although the difference in reading ease between the “hard” and “easy” to read versions is in itself significant, the extent of the effect of this is rather minimal. To remedy this, we could have used mock texts with more substantial reading ease differences but this would have defeated our purpose, since it would have completely removed the external validity from the experiment.

Our findings contribute to the literature in several ways. First of all, whereas previous research into the readability of contract terms tended to focus on the effects of reading ease on the general appeal, comprehension and retention levels, we studied its specific effects on the consumer’s expectations that is to say, the extent to which customers expect their insurer to compensate the damage sustained. Using a large, representative sample, we observed that easier-to-read contract terms raise consumer expectations regarding claims. These results are therefore, on the one hand, consistent with the hypothesis that easier-to-read contracts bolster trust but they also reveal an inherent aspect of trust, namely higher expectations. A second contribution to the literature lies in the fact that we also looked at the effects of the readability of contracts on consumer behaviour in the wake of a conflict (seeking information, advice, and undertaking legal action). Our findings provide partial evidence for this link.

What are the implications of our findings? It is clear that in both the European and the national context, lawmakers, regulators, and courts are increasingly taking an interest in the simplification of legal documentation in consumer markets such as standard contract terms. This is especially the case in the domain of financial consumer products, where complexity of the product is matched by the complexity of the contractual wording used to describe the product. Regulatory standards in this area have been used to encourage financial service providers to switch to “easy to read” general contract terms. Our findings indicate that enhancing reading ease may also inflate consumer expectations with regard to the performance levels of the professional counterparty. These heightened expectations in turn can influence the consumer’s willingness to engage in conflict when such expectations are not met. To be clear, we do not advocate that this should stop policymakers from insisting on improvement of reading ease as a goal in itself but we do nevertheless point out that there is a caveat. The least that can be said is that blindly regulating towards enhancing reading ease without taking into account its effects on consumer attitudes, expectations, and willingness to engage in conflict may result in parts of the picture remaining unseen. It seems to us that consumer trust in the insurance industry will not benefit if “easy to read” contract terms give rise to increased levels of expectation, only for these not to be realised in the subsequent claims process. So, ideally, insurance companies should include a “road testing” phase in their product approval procedure to test both the effect of their use of enhanced reading ease on cognitive aspects such as comprehension levels in their consumer audience as well as the effect on their attitudes and their “thinking and deciding” processes.

Notes

For example, Life Insurance Directive 2002/83/EC Annex III (information for policy holders to be provided in writing in a “clear and accurate manner”); article 10 of E-Commerce Directive 2000/31/EC (certain information to be provided “clearly, comprehensibly, and unambiguously”). Cf. article 7 (2) of Unfair Commercial Practices Directive 2005/29/EC and article 19 (2) of MIFiD Directive 2004/39/EC for similar duties. At the national level, see, e.g., the UK Financial Services Authority (FSA) Insurance: Conduct of Business sourcebook (ICOBS), s. 2.2 “Communications to clients and financial promotions” as well as Banking: Conduct of Business sourcebook (BCOBS), s. 2.2. In the USA, even more specific plain language statutes exist (Kimble 1995).

References

Adler, M. (2012). The plain language movement. In P. M. Tiersma & L. M. Solan (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of language and law (pp. 67–83). Oxford: O.U.P.

Alter, A. L., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2006). Predicting short-term stock fluctuations by using processing fluency. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(24), 9369–9372. doi:10.1073/pnas.0601071103.

Alter, A. L., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2009). Uniting the tribes of fluency to form a metacognitive nation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13(3), 219–235. doi:10.1177/1088868309341564.

Baker, J. A. (2011). And the winner is: How principles of cognitive science resolve the plain language debate. University of Missouri-Kansas City Law Review, 80(2), 287–306.

Becher, S. I., & Unger-Aviram, E. (2010). The law of standard form contracts: Misguided intuitions and suggestions for reconstruction. DePaul Business & Commercial Law Journal, 8(3), 199–227.

Campbell, N. (1999). How New Zealand consumers respond to plain English. Journal of Business Communication, 36(4), 335–361.

Charrow, R. P., & Charrow, V. R. (1979). Making legal language understandable: A psycholinguistic study of jury instructions. Columbia Law Review, 79(7), 1306–1374. doi:10.2307/1121842.

Davis, J. (1977). Protecting consumers from overdisclosure and gobbledygook: an empirical look at the simplification of consumer credit contracts. Virginia Law Review, 63(6), 841–920.

Garrison, L., Hastak, M., Hogarth, J. M., Kleimann, S., & Levy, A. S. (2012). Designing evidence-based disclosures: A case study of financial privacy notices. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 46(2), 204–234. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2012.01226.x

Greene, E., Fogler, K., & Gibson, S. C. (2012). Do people comprehend legal language in wills? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26, 500–507.

Hartley, J., & Trueman, M. (1983). The effects of heading in text on recall, search and retrieval. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 53, 205–214.

Hillman, R. A. (2006). On-line consumer standard-form contracting practices: A survey and discussion of legal implications. In J. K. Winn (Ed.), Consumer protection in the age of the ‘Information Economy’ (p. 283). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Hiltunen, R. (2012). The grammar and structure of legal texts. In P. M. Tiersma & L. M. Solan (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of language and law (pp. 39–51). Oxford: O.U.P.

Kamalski, J. M. H., Lentz, L. R., & Sanders, T. J. M. (2006). Effects of coherence marking on the comprehension and appraisal of discourse. In R. Sun & N. Miyake (Eds.), Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 1575–1580). Mahwah, NJ, USA: Erlbaum.

Kieras, D. E., & Dechert, C. (1985). Rules for comprehensible technical prose: a survey of the psycholinguistic literature University of Michigan Technical Report No. 21.

Kimble, J. (1995). Answering the critics of plain language. The Scribes Journal of Legal Writing, 5(1994–1995), 51–85.

Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1995). Trust in relationships: A model of trust development and decline. In B. B. Bunker & J. Z. Rubin (Eds.), Conflict, cooperation and justice (pp. 133–173). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1996). Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 114–139). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lewicki, R. J., Tomlinson, E. C., & Gillespie, N. (2006). Models of interpersonal trust development: Theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. Journal of Management, 32, 991–1022.

Luth, H. A. (2010). Behavioural economics in consumer policy—the economic analysis of standard terms in consumer contracts revisited (diss. Rotterdam). Antwerpen: Intersentia.

Masson, M. E. J., & Waldron, M. A. (1994). Comprehension of legal contracts by non-experts: Effectiveness of plain language redrafting. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 8, 67–85.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734.

OFT. (2011). Consumer contracts (OFT1312). London: Office of Fair Trading.

Pan, Y., & Zinkhan, G. (2006). Exploring the impact of online privacy disclosures on consumer trust. Journal of Retailing, 82(4), 331–338.

Pander Maat, H., De Boer, N., & Timmermans, C. (2009). De gebruiksvriendelijkheid van hypotheekinformatie: Een lezersonderzoek. Utrecht: Universiteit Utrecht.

Pogrund Stark, D., & Choplin, J. M. (2009). A license to deceive: Enforcing contractual myths despite consumer psychological realities. NYU J. of L. & Business, 5, 617–744.

Reber, R., Winkielman, P., & Schwarz, N. (1998). Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judgments. Psychological Science, 9(1), 45–48. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00008.

Reber, R., Schwarz, N., & Winkielman, P. (2004). Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: Is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(4), 364–382. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_3.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different at all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 393–404.

Schwarz, N. (2004). Metacognitive experiences in consumer judgment and decision making. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14(4), 332–348. doi:10.1207/s15327663jcp1404_2.

Song, H., & Schwarz, N. (2009). If it’s difficult to pronounce, it must be risky—Fluency, familiarity, and risk perception. Psychological Science, 20, 135–138.

Stolle, D. P. (1998). A social scientific look at the effects and effectiveness of plain language contract drafting. (PhD), University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/dissertations/AAI9839149 (Paper AAI9839149)

Tiersma, P. M., & Curtis, M. (2008). Testing the comprehensibility of jury instructions: California’s old and new instructions on circumstantial evidence. Journal of Court Innovation, 1, 231–261.

Treur, H. F., & van Rijckevorsel, J. L. A. (2004). CVS Consumentenonderzoek—Eerste editie—In opdracht van de Commissie Consumentenbeleid van het Verbond van Verzekeraars. Den Haag: Verbond van Verzekeraars.

Van Boom, W. H. (2014). Begrijpelijke hypotheekvoorwaarden en consumentengedrag. In T. M. Berkhout & A. A. van Velten (Eds.), Perspectieven voor vastgoedfinanciering (pp. 45–80). Amsterdam: Stichting Fundatie Bachiene.

Van Dam, M. R., Van Boom, W. H., & Tuil, M. L. (2012). Tekstbegrip en klantbelang bij financiële producten. In E. M. Dieben & F. M. A. ’t Hart (Eds.), Klantbelang Centraal (Financieel Juridische Reeks 4) (pp. 109–124). Amsterdam: NIBE-SVV.

Winkielman, P., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2001). Mind at ease puts a smile on the face: psychophysiological evidence that processing facilitation elicits positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 989–1000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Boom, W.H., Desmet, P. & Van Dam, M. “If It’s Easy to Read, It’s Easy to Claim”—The Effect of the Readability of Insurance Contracts on Consumer Expectations and Conflict Behaviour. J Consum Policy 39, 187–197 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-016-9317-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-016-9317-9