Abstract

The purpose of this study is to obtain a consensus for the therapy of B3 lesions. The first International Consensus Conference on lesions of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions) including atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), flat epithelial atypia (FEA), classical lobular neoplasia (LN), papillary lesions (PL), benign phyllodes tumors (PT), and radial scars (RS) took place in January 2016 in Zurich, Switzerland organized by the International Breast Ultrasound School and the Swiss Minimally Invasive Breast Biopsy group—a subgroup of the Swiss Society of Senology. Consensus recommendations for the management and follow-up surveillance of these B3 lesions were developed and areas of research priorities were identified. The consensus recommendation for FEA, LN, PL, and RS diagnosed on core needle biopsy or vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB) is to therapeutically excise the lesion seen on imaging by VAB and no longer by open surgery, with follow-up surveillance imaging for 5 years. The consensus recommendation for ADH and PT is, with some exceptions, therapeutic first-line open surgical excision. Minimally invasive management of selected B3 lesions with therapeutic VAB is acceptable as an alternative to first-line surgical excision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast lesions classified as lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) are a heterogeneous group of abnormalities with a borderline histological spectrum, and a variable but low risk of associated malignancy [1]. They encompass a spectrum of histological diagnoses including atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), flat epithelial atypia (FEA), classical lobular neoplasia (LN), papillary lesions (PL), benign phyllodes tumors (PT), and radial scars (RS), each with variable rates of upgrade or long-term increased risk of breast cancer [2]. Histological diagnosis of a B3 lesion is made by either core needle biopsy (CNB) mostly using a 14G spring-loaded CNB or by vacuum-assisted biopsy (VAB) using a 7G–11G device either under ultrasound, stereotactic, or MRI guidance following informed consent and local anesthetic. Occasionally it is an incidental finding on a specimen which has been excised surgically.

Between 4 and 9 % of all CNBs are classified as B3 lesions with numbers increasing due to advances in diagnostic imaging such as highly sensitive MRI scanning and interventional techniques such as VAB [3]. However, the positive predictive value for malignancy has been falling (from 29 to 10 %) [4, 5]. Management of B3 lesions provides a challenge to the multidisciplinary team as diagnostic surgical excision is no longer the only available treatment. Minimally invasive breast biopsy, or VAB, facilitates removal of larger volumes of tissue than a CNB equivalent to a small wide local excision and allows the same diagnostic accuracy as open surgery [6]. For many B3 lesions, instead of surgical excision, VAB may be sufficient for therapeutic excision which would benefit the patient and save on healthcare costs by obviating the need for surgery [7].

The evidence base for appropriate management of B3 lesions in the breast is limited. Practice varies greatly from country to country. This article provides a review of the literature for the six different B3 lesions documented including the analysis of 2 large Swiss B3 histology databases followed by consensus recommendations by an expert panel taken after a voting by the participants of the symposium organized by the International Breast Ultrasound School (IBUS) and the Swiss MIBB group—a subgroup of the Swiss Society of Senology in January 2016, in Zurich, Switzerland.

Methodology

The first International Consensus Conference on lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) was held with international experts as part of the IBUS seminar in January 2016 in Zurich. These meetings have been held bi-annually since 2001 with discussion of therapeutic management options for B3 lesions. The meeting in January 2016 had 90 participants with the multidisciplinary expert panel (all the aforementioned authors) comprising nine radiologists, two pathologists, one surgeon, and three gynecologists. Each of the B3 lesions was discussed in turn with reference to the published literature and the analysis of the MIBB [8] working group database (histology from 22,072 VABs).

A set of recommendations for the management of B3 breast lesions was prepared building on the current practice of the Swiss MIBB working group. Recommendations for management of B3 breast lesions following histological diagnosis were either: (i) surveillance (defined as 6 monthly or yearly mammography and/or ultrasound, depending on the imaging findings) [9], (ii) therapeutic VAB excision, or (iii) therapeutic open surgical excision. All participants at the Consensus Conference were invited to vote on all recommendations and 50 of the 90 participants decided to. 27 (57 %) were radiologists, 2 (4 %) pathologists, 2 (4 %) surgeons, and 16 (34 %) gynecologists. Nearly two-thirds of those voting had more than 10 years’ experience in breast disease diagnosis and management.

There were 3344 “pure” B3 lesions in the MIBB database (15 % of all lesions). Following presentations of each B3 lesion in detail reviewing the published literature, three questions were asked in turn:

Q1. If a CNB returned a B3 lesion on histology, should the lesion be therapeutically excised?

Q2. If so, should it be excised therapeutically using VAB?

Q3. If the VAB returned a B3 lesion on histology and if the lesion was completely removed on imaging, is surveillance acceptable or should a repeat VAB or surgical excision be performed?

A panel discussion followed the voting and consensus recommendations were agreed for the management of each B3 lesion.

Results

Table 1 illustrates the number of cases in each B3 lesion category that underwent therapeutic surgical excision compared to those that did not following VAB. Table 2 illustrates the upgrade rate to invasive malignancy for each B3 lesion in cases that underwent therapeutic open surgical excision following VAB. Table 3 documents the voting results for each of the B3 lesions and Table 4 shows the overall consensus recommendations for the management of B3 lesions.

Atypical ductal hyperplasia

The histopathologic features of ADH are essentially those of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). If less than 2 mm, the lesion is classified as ADH and if more than 2 mm, it is classified as low-grade DCIS [10, 11]. This is the fundamental problem of ADH diagnosed by CNB where often only parts of the lesion have been excised as VAB or surgical excision may upgrade the diagnosis from a B3 to a B5a lesion and this is why most guidelines recommend surgical excision following a CNB diagnosis of ADH [12]. Stereotactic VAB underestimation rates range from 9 to 58 % [13–25]. Even with complete removal of malignant microcalcifications by VAB, underestimation rates up to 17 % are documented [26–29]. The highest underestimation rates (22–65 %) are published for ultrasound-guided 14G CNB [21, 22, 25, 30–34] while ultrasound-guided VABs have much lower rates of underestimation (0–22 %) [33, 35]. Grady et al. found no underestimation in lesions completely removed by 8 G ultrasound-guided VAB [35]. For MRI-guided VAB only two studies exist regarding underestimation of ADH showing underestimation rates of 32 and 38 %, respectively [36, 37].

In studies analyzing patients on surveillance without surgical treatment following a VAB diagnosis of ADH, long-term upgrade rates to invasive breast cancer of 3–8 % are reported [19, 26]. After therapeutic surgical excision of ADH, patients had a fourfold increased risk of developing breast cancer in either breast with a cumulative incidence of 30 % in 25 years [10, 11, 38, 39]. Currently, there is very little data to indicate that lesions smaller than 6 mm completely excised by VAB with less than 2 foci of ADH may safely avoid surgery [14, 19, 21, 26, 40].

736 cases of ADH from the MIBB database were reviewed. 439 (60 %) had subsequent therapeutic open surgical excision following VAB (Table 1) with an upgrade rate of 5 % (22/439) to invasive malignancy (B5b) (Table 2).

If a CNB returned ADH on histology

100 % of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 24 % thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 73 % thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned ADH on histology

51 % of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 42 % thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 3).

Consensus recommendation

A lesion containing ADH which is visible on imaging should undergo therapeutic open surgical excision. If a unifocal ADH lesionFootnote 1 has been completely removed by VAB, surveillance is justified. Otherwise open surgery is still recommended (Table 4).

Flat epithelial atypia

FEA is defined as a neoplastic proliferation of the terminal ductulo-lobular units (TDLU) by a few layers of cells with low-grade (monomorphic) atypia [2, 41, 42]. Histopathology of FEA lesions encompasses the proliferation of round and uniform cells (defined as low-grade atypia) exhibiting inconspicuous nuclei [2, 41, 42]. There is often associated calcification. An FEA lesion lacks secondary architecture such as roman bridges or cellular tufts and exhibits a characteristic immunophenotype of negative low-molecular weight cytokeratins and high regulation of estrogen receptors [2, 41, 42]. The mammographic appearance of FEA is mostly seen as microcalcifications which are irregular and branching with accompanying marked duct dilatation [2, 41, 42]. Coexisting lesions both on imaging and on histopathology encompass classical LN, other benign columnar cell lesions, low-grade intraductal proliferations such as ADH/DCIS, or tubular carcinoma [2, 41, 42].

The risk of developing breast cancer with a diagnosis of FEA is estimated at 1–2 times higher than those without FEA [2, 41, 42]. ADH and DCIS are the most frequent pathologies found following surgical excision with their incidence varying from 0 to 40 %. Underestimation rates are between 0–20 % if FEA is diagnosed on core biopsy and are very similar if diagnosed on VAB (0–21 %) [43–48]. Current German (AGO) 2015 guidelines [12], do not recommend therapeutic open surgical excision of FEA diagnosed on CNB or VAB if the lesion is small (maximum 2 TDLU) and the imaging abnormality was completely removed by VAB. Surgical excision is recommended if there is radiopathological discrepancy, if the lesion is visible on imaging and the imaging classification is BIRADS 4. For BIRADS 3 lesions, completely removed by VAB, open surgery is not considered necessary [43–48].

773 cases of FEA from the MIBB database were reviewed. 177 (23 %) had subsequent therapeutic open surgical excision following VAB (Table 1) with an upgrade rate of 9 % (16/191) to invasive malignancy (B5b) (Table 2).

If a CNB returned FEA on histology

97 % of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 70 % thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 27 % thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned FEA on histology

3 % of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 94 % thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 3).

Consensus recommendation

A lesion containing FEA, which is visible on imaging should undergo therapeutic excision with VAB. Thereafter surveillance is justified (Table 4).

Classical lobular neoplasia

Classical LN encompasses a spectrum of atypical epithelial proliferations in the TDLU of the breast [2, 41, 42]. The histology consists of non-cohesive proliferating epithelial cells with or without pagetoid involvement of the terminal ducts [2, 41, 42]. There are several nomenclatures used for LN: The classical type of LN covers all lobular lesions, which develop in the TDLU except those with pleomorphic or extensive variants. The older nomenclature of atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) refers to the same lesion but to different extents, defined as ALH if less than 50 % of the given TDLU are involved and LCIS if more than 50 % is involved [2, 41, 42]. The World Health Organization (WHO) also applies the term lobular intraepithelial lesion (LIN), which can be classified as LIN 1, 2, and 3, with LIN 1 formally being equivalent to ALH, LIN2 to LCIS, and LIN3 to the pleomorphic or extensive LN variants with or without necrosis [2, 41, 42]. MIBB classification of lobular neoplasia categorizes all lesions (classical LN, ALH, LCIS, LIN1, LIN2) as B3, but LIN 3 or pleomorphic LN or those with extensive necrosis are classified as B5a. The MIBB classification and the WHO recommend the use of the histological terms classical LN as B3 and pleomorphic LN as B5a [2, 12].

The incidence of classical LN has been increasing and varies from 0.5 to 4 %. It can occur at all ages but predominantly in premenopausal women. Most lesions present incidentally without any palpable mass and less than half of classical LN lesions have associated calcification. Published data on the risk of developing breast cancer after diagnosis on CNB or VAB show, a relative risk of 1–2 % per year, 15–17 % after 15 years, and 35 % after 35 years with relatively equal rates of ipsi- and contralateral breast cancer (8.7 and 6.7 %, respectively) [2, 49–53]. The upgrade rate after classical LN diagnosis on CB or VAB is variable in the literature, ranging from 0 to 50 % which can at least partially be explained by variation in study design and inconsistent use of ALH, LCIS, and LN nomenclatures [2, 41]. In one study, underestimation was found to be 4 % in classical LN cases when LN was an incidental finding and 18 %, when LN represented the radiologic targets by D’Alfonso et al. [50]. Higher upgrade rates were associated with cases that demonstrated mass lesions and calcification on imaging or with radiopathological discordance. Lower underestimation rates were detected in classical LN cases, where no residual calcification was found after biopsy, calcification was incidental, and there was complete concordance between histological and imaging findings [2, 41, 50].

The WHO recommends surgical excision after classical LN diagnosis on CNB or VAB if there is another B3 lesion present, if another coexisting lesion warrants excision alone, if there is a mass lesion on imaging, or in any case of radiopathological discordance [2, 41]. The German AGO 2015 guidelines favor open excision only if there is a B5a component, if classical LN is extensive, in the presence of necrosis on the CNB or VAB, or in cases of discordance with imaging [12]. Open surgical excision is therefore not considered necessary if there is a complete concordance between histology and imaging, if the imaging finding is classified as BIRADS 3, or of LN is a focal finding and is not associated with calcifications [2, 12, 41].

546 cases of classical LN from the MIBB database were reviewed. 191 (35 %) had subsequent therapeutic open surgical excision following VAB (Table 1) with an upgrade rate of 12.6 % (24/191) to invasive malignancy (B5b) (Table 2).

If a CNB returned classical LN on histology

91 % of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 58 % thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 42 % thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned classical LN on histology

13 % of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 87 % thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 3).

Consensus recommendation

A lesion containing classical LN lesion, which is visible on imaging should undergo therapeutic excision with VAB. Thereafter surveillance is justified (Table 4).

Papillary lesion

PLs represent up to 5 % of all biopsied breast lesions [54–57]. The term PL comprises a heterogeneous group of epithelial lesions such as intraductal papilloma, intraductal papilloma with ADH, intraductal papilloma with DCIS, papillary DCIS, encapsulated papillary carcinoma, solid papillary carcinoma, and invasive papillary carcinoma [2]. PLs demonstrate intra-lesional heterogeneity and can be associated with small foci of ADH or DCIS within the PL or in the adjacent tissue which may be missed by limited sampling with CNB. When describing PL, only PL without atypia should be considered, as a lesion with atypia should be considered within the higher class lesions (e.g., ADH) and offered therapeutic open surgical excision.

Upgrade rates after surgical excision of benign papillomata diagnosed following CNB or VAB vary from 0 to 28 % with atypical cells and from 0 to 20 % for invasive cancer [58–60]. Generally, understaging of invasive malignancy is reduced if multiple biopsy cores are taken or if a larger biopsy needles are employed such as in VAB. Only one study by Chang et al. evaluated the accuracy of VAB in PL without atypia by open surgical excision following VAB with no upgrade to malignancy but an upgrade of 18.3 % to atypia [61]. Most studies following up VAB excision of PL without atypia did not observe any upgrade to malignancy with at least 2 years of surveillance [60, 62, 63]. One recorded a minimal underestimation of 1.4 % [64] and another 3.2 % [65].

The upgrade rate to malignancy following VAB in the MIBB database was 7.7 % for PL without atypia which is higher than in the documented literature. One reason might be the fact that the size of the PL was not recorded, implying that some PL might not have been completely removed. Mosier et al. removed only lesions smaller than 15 mm (range 3–15 mm) to ensure the complete removal of the PL [62]. With this approach, they had no upgrades to malignancy after nearly 9 years. Due to difficulties in excluding malignancy with small tissue samples at CNB, heterogeneity of PLs, and an upgrade rate to carcinoma of up to 20 % [58], the current recommendation is to completely remove PL without atypia, either by surgery or VAB [58–60].

954 cases of PL from the MIBB database have been reviewed. 154 (16 %) had subsequent therapeutic open surgical excision following VAB (Table 1) with an upgrade rate of 2.6 % (4/154) to invasive malignancy (B5b) (Table 2).

If a CNB returned PL on histology

100 % of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 84 % thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 11 % thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned PL on histology

9 % of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 91 % thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 3).

Consensus recommendation

A PL lesion, which is visible on imaging should undergo therapeutic excision with VAB. Thereafter surveillance is justified (Table 4).

Phyllodes tumor

PTs are rare fibroepithelial neoplasms accounting for less than 1 % of primary breast tumors [2, 66]. Histologically, they are classified as benign, borderline, and malignant with the first two subtypes categorized as B3 lesions [67]. The majority of PTs are benign, (63–78 %) with borderline PTs diagnosed in 11–30 % of cases [2]. Incidence is highest in women aged 40–51 years [68, 69]. Overlapping clinical, radiological, and histopathological features may make differentiation from benign fibroadenomata challenging at times, however accurate preoperative diagnosis is essential to establish the most appropriate therapeutic approach.

Underestimation rates of PTs following CNB range from 8 to 39 % (mean 20 %) [70, 71].Concordance rates between CNB and surgical excision for benign and borderline/malignant PTs are between 38.5 and 82 % and 74.7–100 %, respectively [72], with higher concordance of up to 90 % following VAB [73]. Youk et al. documented upgrades from benign to malignant PTs in 8.7 % of patients, with higher underestimation rates found in pre-excisional ultrasound BIRADS 4 lesions and higher classifications [73]. Recurrence rates for benign PTs are similar following ultrasound -guided VAB (0–19.4 %) and surgical excision (5–17 %) [74–76], but higher for borderline PTs following surgical excision (14–25 %) [77, 78]. The majority of published studies recommend open surgical excision for all histological PT-subtypes, despite the fact that the recurrence rate for benign PTs after VAB and surgical excision do not vary significantly [73–76, 79–81].

18 cases of PT from the MIBB database have been reviewed. 3 (17 %) had subsequent therapeutic open surgical excision following VAB (Table 1) with an upgrade rate of 0 % to invasive malignancy (B5b) (Table 2).

If a CNB returned PT on histology

91 % of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 51 % thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 46 % thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned PT on histology

11 % of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 83 % thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 3).

Consensus recommendation

A PT lesion, which is visible on imaging should undergo therapeutic open surgical excision with clear margins. If a VAB shows a benign PT, surveillance is justified, while borderline and malignant PTs require re-excision to obtain clear margins (Table 4).

Radial scar

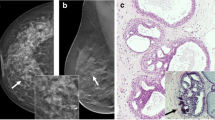

RS or complex sclerosing lesions (CSL) of the breast are characterized by a stellate-like distortion. The nomenclature depends on the size of the lesion which is defined as radial scar if the focus is less than 1 cm or complex sclerosing lesion if over 1 cm [2, 41]. Histopathology of a RS/CSL involves a stellate-like elastosis with or without the presence of associated lobulocentric cysts, usual ductal hyperplasia, adenosis, and microcalcifications. The adenosis may evolve the elastic fibers resulting in entrapped glands, which may mimic a highly differentiated neoplastic glandular proliferation [2, 41]. On mammography, RS/CSL mostly appear as a stellate lesion which mimics an invasive carcinoma. The incidence is variable being 4–9 % in population-based pathology databases, but being significantly higher, up to 63 % in sole pathology literature [2, 41].

The prognosis of RS/CSL depends on the presence of associated atypia [2, 41, 82–87]. Based on correlation between imaging and pathology, RS/CSL without atypia following CNS or VAB are unlikely to have malignancy in the surgical excision specimen if the lesion is less than 6 mm on imaging and the patients are younger than 40 years or older than 60 years [82–87]. The relative risk of developing breast cancer given the presence of a RS/CSL without atypia varies between 1.1 and 3.0 % [88–90]. Conversely, RS/CSL showing cytological or histological atypia, have a higher relative risk of 2.8–6.7 % particularly in patients over 50 years of age [88–90]. Underestimation rates for pure RS/CSL vary between 1 and 28 % following CNB and 8 % following VAB [2, 41, 82–87]. The AGO 2015 and WHO 2012 guidelines recommend surveillance if the imaging findings have been completely excised at VAB and no atypia was found in the histological examination. RS/CSL with atypia on histology following CNB/VAB should undergo therapeutic open surgical excision [2, 12, 41, 88–90].

317 cases of RS/CSL from the MIBB database have been reviewed. 46 (15 %) had subsequent therapeutic open surgical excision following VAB (Table 1) with an upgrade rate of 2 % (1/46) to invasive malignancy (B5b) (Table 2).

If a CNB returned RS/CSL on histology

85 % of the participants thought the lesion should be excised. 72 % thought therapeutic VAB excision was acceptable and 26 % thought therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed.

If a VAB returned RS/CSL on histology

2 % of the participants thought that therapeutic open surgical excision should be performed and 98 % thought that surveillance was adequate (Table 3).

Consensus recommendation

A RS/CSL lesion, which is visible on imaging should undergo therapeutic excision with VAB. Thereafter surveillance is justified (Table 4).

Discussion

The expert consensus panel and participants agreed that for most of the B3 lesions (except for ADH and PT), surgery can be avoided and therapeutic excision with VAB of a lesion which is visible on imaging is an acceptable alternative. However, as data are lacking at present the panel still recommends open surgery in cases of ADH. As more data on the minimally invasive conservative management of B3 lesions become available, a more conservative approach may also be justified in cases of ADH. The outcome from this consensus meeting is a progressive move forward to a more conservative approach to managing these lesions in which open surgery can potentially be avoided. Studies following a diagnosis of low-grade DCIS have shown excellent survival rates of more than 98 % at ten years after diagnosis without surgery [91, 92] which have prompted randomized phase III trials for surgery versus no surgery in low- and intermediate-grade DCIS [93, 94]. Therefore it is becoming clear, that it is even more reasonable to try to avoid unnecessary open surgery or overtreatment in some women. It is important to emphasize that these recommendations cannot exclude a false-negative diagnosis in every individual patient and each case should be discussed on an individual basis with a multidisciplinary team taking into account the imaging features, lesion size, practicality and technical feasibility of minimally invasive management, patient demographics, and patient preference.

Notes

Focal ADH is not defined in the WHO classification and mentioning the exact dimension of ADH lesions below 2 mm is not mandatory. However recent literature data suggest, that ADH lesions (less than 2 mm in extension max. 2 cross sections) may not have to undergo surgical excision. These data need further validation.

References

Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, Tornberg S, Holland R, von Karsa L (2008) European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosis. Fourth edition–summary document. Ann Oncol 19:614–622

Lakhani SREI, Schnitt SJ, Tan PH, van de Vijver MJ (2012) WHO classification of tumours of the breast, fourth edition 2012. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Pathology N-oDSotNCGfBS. Guidelines for non-operative diagnostic procedures and reporting in breast cancer screening. NHSBSP Publication No 50. (2001)

El-Sayed ME, Rakha EA, Reed J, Lee AH, Evans AJ, Ellis IO (2008) Audit of performance of needle core biopsy diagnoses of screen detected breast lesions. Eur J Cancer 44:2580–2586

Rakha EA, Ho BC, Naik V, Sen S, Hamilton LJ, Hodi Z et al (2011) Outcome of breast lesions diagnosed as lesion of uncertain malignant potential (B3) or suspicious of malignancy (B4) on needle core biopsy, including detailed review of epithelial atypia. Histopathology 58:626–632

O’Flynn EA, Wilson AR, Michell MJ (2010) Image-guided breast biopsy: state-of-the-art. Clin Radiol 65:259–270

Alonso-Bartolome P, Vega-Bolivar A, Torres-Tabanera M, Ortega E, Acebal-Blanco M, Garijo-Ayensa F et al (2004) Sonographically guided 11-G directional vacuum-assisted breast biopsy as an alternative to surgical excision: utility and cost study in probably benign lesions. Acta Radiol 45:390–396

Saladin C, Haueisen H, Kampmann G, Oehlschlegel C, Seifert B, Rageth L et al (2015) Lesions with unclear malignant potential (B3) after minimally invasive breast biopsy: evaluation of vacuum biopsies performed in Switzerland and recommended further management. Acta Radiol. 0284185115610931

Neuschatz AC, DiPetrillo T, Safaii H, Price LL, Schmidt-Ullrich RK, Wazer DE (2003) Long-term follow-up of a prospective policy of margin-directed radiation dose escalation in breast-conserving therapy. Cancer 97:30–39

Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, Rados MS (1985) Atypical hyperplastic lesions of the female breast. A long-term follow-up study. Cancer. 55:2698–2708

Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ (1990) A comparison of the results of long-term follow-up for atypical intraductal hyperplasia and intraductal hyperplasia of the breast. Cancer 65:518–529

(AGO) AGO. Guidelines of the AGO breast committee: lesions of uncertain malignant potential (B3) (ADH, LIN, FEA, Papilloma, Radial Scar). http://www.ago-onlinede/fileadmin/downloads/leitlinien/mamma/Maerz2016/en/2016E%2006_Lesions%20of%20Uncertain%20Malignant%20Potential%20%28B3%29pdf. 2016

Brem RF, Behrndt VS, Sanow L, Gatewood OM (1999) Atypical ductal hyperplasia: histologic underestimation of carcinoma in tissue harvested from impalpable breast lesions using 11-gauge stereotactically guided directional vacuum-assisted biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 172:1405–1407

Deshaies I, Provencher L, Jacob S, Cote G, Robert J, Desbiens C et al (2011) Factors associated with upgrading to malignancy at surgery of atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed on core biopsy. Breast 20:50–55

Houssami N, Ciatto S, Ellis I, Ambrogetti D (2007) Underestimation of malignancy of breast core-needle biopsy: concepts and precise overall and category-specific estimates. Cancer 109:487–495

Jackman RJ, Nowels KW, Rodriguez-Soto J, Marzoni FA Jr, Finkelstein SI, Shepard MJ (1999) Stereotactic, automated, large-core needle biopsy of nonpalpable breast lesions: false-negative and histologic underestimation rates after long-term follow-up. Radiology 210:799–805

Kettritz U, Rotter K, Schreer I, Murauer M, Schulz-Wendtland R, Peter D et al (2004) Stereotactic vacuum-assisted breast biopsy in 2874 patients: a multicenter study. Cancer 100:245–251

Teng-Swan Ho J, Tan PH, Hee SW, Su-Lin Wong J (2008) Underestimation of malignancy of atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed on 11-gauge stereotactically guided mammotome breast biopsy: an Asian breast screen experience. Breast 17:401–406

Ancona A, Capodieci M, Galiano A, Mangieri F, Lorusso V, Gatta G (2011) Vacuum-assisted biopsy diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia and patient management. Radiol Med 116:276–291

Bedei L, Falcini F, Sanna PA, Casadei Giunchi D, Innocenti MP, Vignutelli P et al (2006) Atypical ductal hyperplasia of the breast: the controversial management of a borderline lesion: experience of 47 cases diagnosed at vacuum-assisted biopsy. Breast 15:196–202

Gumus H, Mills P, Gumus M, Fish D, Jones S, Jones P et al (2013) Factors that impact the upgrading of atypical ductal hyperplasia. Diagn Interv Radiol 19:91–96

Londero V, Zuiani C, Linda A, Battigelli L, Brondani G, Bazzocchi M (2011) Borderline breast lesions: comparison of malignancy underestimation rates with 14-gauge core needle biopsy versus 11-gauge vacuum-assisted device. Eur Radiol 21:1200–1206

Pandelidis S, Heiland D, Jones D, Stough K, Trapeni J, Suliman Y (2003) Accuracy of 11-gauge vacuum-assisted core biopsy of mammographic breast lesions. Ann Surg Oncol 10:43–47

Polom K, Murawa D, Kurzawa P, Michalak M, Murawa P (2012) Underestimation of cancer in case of diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) by vacuum assisted core needle biopsy. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 17:129–133

Sohn V, Keylock J, Arthurs Z, Wilson A, Herbert G, Perry J et al (2007) Breast papillomas in the era of percutaneous needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol 14:2979–2984

Forgeard C, Benchaib M, Guerin N, Thiesse P, Mignotte H, Faure C et al (2008) Is surgical biopsy mandatory in case of atypical ductal hyperplasia on 11-gauge core needle biopsy? A retrospective study of 300 patients. Am J Surg 196:339–345

Kohr JR, Eby PR, Allison KH, DeMartini WB, Gutierrez RL, Peacock S et al (2010) Risk of upgrade of atypical ductal hyperplasia after stereotactic breast biopsy: effects of number of foci and complete removal of calcifications. Radiology 255:723–730

McGhan LJ, Pockaj BA, Wasif N, Giurescu ME, McCullough AE, Gray RJ (2012) A typical ductal hyperplasia on core biopsy: an automatic trigger for excisional biopsy? Ann Surg Oncol 19:3264–3269

Villa A, Tagliafico A, Chiesa F, Chiaramondia M, Friedman D, Calabrese M (2011) Atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed at 11-gauge vacuum-assisted breast biopsy performed on suspicious clustered microcalcifications: could patients without residual microcalcifications be managed conservatively? AJR Am J Roentgenol 197:1012–1018

Hsu HH, Yu JC, Hsu GC, Yu CP, Chang WC, Tung HJ et al (2012) Atypical ductal hyperplasia of the breast diagnosed by ultrasonographically guided core needle biopsy. Ultraschall Med 33:447–454

Youk JH, Kim EK, Kim MJ (2009) Atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosed at sonographically guided 14-gauge core needle biopsy of breast mass. AJR Am J Roentgenol 192:1135–1141

Chae BJ, Lee A, Song BJ, Jung SS (2009) Predictive factors for breast cancer in patients diagnosed atypical ductal hyperplasia at core needle biopsy. World J Surg Oncol 7:77

Grady I, Gorsuch H, Wilburn-Bailey S (2005) Ultrasound-guided, vacuum-assisted, percutaneous excision of breast lesions: an accurate technique in the diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia. J Am Coll Surg 201:14–17

Jang M, Cho N, Moon WK, Park JS, Seong MH, Park IA (2008) Underestimation of atypical ductal hyperplasia at sonographically guided core biopsy of the breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol 191:1347–1351

Lourenco AP, Khalil H, Sanford M, Donegan L (2014) High-risk lesions at MRI-guided breast biopsy: frequency and rate of underestimation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 203:682–686

Hartmann LC, Radisky DC, Frost MH, Santen RJ, Vierkant RA, Benetti LL et al (2014) Understanding the premalignant potential of atypical hyperplasia through its natural history: a longitudinal cohort study. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 7:211–217

Liberman L, Holland AE, Marjan D, Murray MP, Bartella L, Morris EA et al (2007) Underestimation of atypical ductal hyperplasia at MRI-guided 9-gauge vacuum-assisted breast biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 188:684–690

Ely KA, Carter BA, Jensen RA, Simpson JF, Page DL (2001) Core biopsy of the breast with atypical ductal hyperplasia: a probabilistic approach to reporting. Am J Surg Pathol 25:1017–1021

Sanders ME, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, Page DL (2005) The natural history of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in women treated by biopsy only revealed over 30 years of long-term follow-up. Cancer 103:2481–2484

Sneige N, Lim SC, Whitman GJ, Krishnamurthy S, Sahin AA, Smith TL et al (2003) Atypical ductal hyperplasia diagnosis by directional vacuum-assisted stereotactic biopsy of breast microcalcifications. Considerations for surgical excision. Am J Clin Pathol 119:248–253

Dabbs DJ (2012) Breast pathology

Tavassoli FA DP (2003) (ed). Pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs

Chivukula M, Bhargava R, Tseng G, Dabbs DJ (2009) Clinicopathologic implications of “flat epithelial atypia” in core needle biopsy specimens of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol 131:802–808

Darvishian F, Singh B, Simsir A, Ye W, Cangiarella JF (2009) Atypia on breast core needle biopsies: reproducibility and significance. Ann Clin Lab Sci 39:270–276

Ingegnoli A, d’Aloia C, Frattaruolo A, Pallavera L, Martella E, Crisi G et al (2010) Flat epithelial atypia and atypical ductal hyperplasia: carcinoma underestimation rate. Breast J 16:55–59

Kunju LP, Kleer CG (2007) Significance of flat epithelial atypia on mammotome core needle biopsy: should it be excised? Hum Pathol 38:35–41

Piubello Q, Parisi A, Eccher A, Barbazeni G, Franchini Z, Iannucci A (2009) Flat epithelial atypia on core needle biopsy: which is the right management? Am J Surg Pathol 33:1078–1084

Senetta R, Campanino PP, Mariscotti G, Garberoglio S, Daniele L, Pennecchi F et al (2009) Columnar cell lesions associated with breast calcifications on vacuum-assisted core biopsies: clinical, radiographic, and histological correlations. Mod Pathol 22:762–769

Bodian CA, Perzin KH, Lattes R (1996) Lobular neoplasia. long term risk of breast cancer and relation to other factors. Cancer 78:1024–1034

D’Alfonso TM, Wang K, Chiu YL, Shin SJ (2013) Pathologic upgrade rates on subsequent excision when lobular carcinoma in situ is the primary diagnosis in the needle core biopsy with special attention to the radiographic target. Arch Pathol Lab Med 137:927–935

Haagensen DE Jr, Mazoujian G, Dilley WG, Pedersen CE, Kister SJ, Wells SA Jr (1979) Breast gross cystic disease fluid analysis. I. isolation and radioimmunoassay for a major component protein. J Natl Cancer Inst 62:239–247

Ottesen GL, Graversen HP, Blichert-Toft M, Christensen IJ, Andersen JA (2000) Carcinoma in situ of the female breast. 10 year follow-up results of a prospective nationwide study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 62:197–210

Page DL, Kidd TE Jr, Dupont WD, Simpson JF, Rogers LW (1991) Lobular neoplasia of the breast: higher risk for subsequent invasive cancer predicted by more extensive disease. Hum Pathol 22:1232–1239

Liberman L, Bracero N, Vuolo MA, Dershaw DD, Morris EA, Abramson AF et al (1999) Percutaneous large-core biopsy of papillary breast lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 172:331–337

Mercado CL, Hamele-Bena D, Singer C, Koenigsberg T, Pile-Spellman E, Higgins H et al (2001) Papillary lesions of the breast: evaluation with stereotactic directional vacuum-assisted biopsy. Radiology 221:650–655

Philpotts LE, Shaheen NA, Jain KS, Carter D, Lee CH (2000) Uncommon high-risk lesions of the breast diagnosed at stereotactic core-needle biopsy: clinical importance. Radiology 216:831–837

Reynolds HE (2000) Core needle biopsy of challenging benign breast conditions: a comprehensive literature review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 174:1245–1250

Chang JM, Moon WK, Cho N, Han W, Noh DY, Park IA et al (2011) Management of ultrasonographically detected benign papillomas of the breast at core needle biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 196:723–729

Bianchi S, Bendinelli B, Saladino V, Vezzosi V, Brancato B, Nori J et al (2015) Non-malignant breast papillary lesions - b3 diagnosed on ultrasound–guided 14-gauge needle core biopsy: analysis of 114 cases from a single institution and review of the literature. Pathol Oncol Res 21:535–546

Kim MJ, Kim SI, Youk JH, Moon HJ, Kwak JY, Park BW et al (2011) The diagnosis of non-malignant papillary lesions of the breast: comparison of ultrasound-guided automated gun biopsy and vacuum-assisted removal. Clin Radiol 66:530–535

Chang JM, Han W, Moon WK, Cho N, Noh DY, Park IA et al (2011) Papillary lesions initially diagnosed at ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted breast biopsy: rate of malignancy based on subsequent surgical excision. Ann Surg Oncol 18:2506–2514

Mosier AD, Keylock J, Smith DV (2013) Benign papillomas diagnosed on large-gauge vacuum-assisted core needle biopsy which span < 1.5 cm do not need surgical excision. Breast J. 19:611–617

Youk JH, Kim MJ, Son EJ, Kwak JY, Kim EK (2012) US-guided vacuum-assisted percutaneous excision for management of benign papilloma without atypia diagnosed at US-guided 14-gauge core needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol 19:922–928

Wyss P, Varga Z, Rossle M, Rageth CJ (2014) Papillary lesions of the breast: outcomes of 156 patients managed without excisional biopsy. Breast J 20:394–401

Yamaguchi R, Tanaka M, Tse GM, Yamaguchi M, Terasaki H, Hirai Y et al (2015) Management of breast papillary lesions diagnosed in ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted and core needle biopsies. Histopathology 66:565–576

Buchanan EB (1995) Cystosarcoma phyllodes and its surgical management. Am surg 61:350–355

Yang X, Kandil D, Cosar EF, Khan A (2014) Fibroepithelial tumors of the breast: pathologic and immunohistochemical features and molecular mechanisms. Arch Pathol Lab Med 138:25–36

Krishnamurthy S, Ashfaq R, Shin HJ, Sneige N (2000) Distinction of phyllodes tumor from fibroadenoma: a reappraisal of an old problem. Cancer 90:342–349

Tse GM, Niu Y, Shi HJ (2010) HJ Phyllodes tumor of the breast: an update. Breast cancer 17:29–34

Bode MK, Rissanen T, Apaja-Sarkkinen M (2007) Ultrasonography and core needle biopsy in the differential diagnosis of fibroadenoma and tumor phyllodes. Acta Radiol 48:708–713

Youn I, Choi SH, Moon HJ, Kim MJ, Kim EK (2013) Phyllodes tumors of the breast: ultrasonographic findings and diagnostic performance of ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy. Ultrasound Med Biol 39:987–992

Choi J, Koo JS (2012) Comparative study of histological features between core needle biopsy and surgical excision in phyllodes tumor. Pathol Int 62:120–126

Youk JH, Kim H, Kim EK, Son EJ, Kim MJ, Kim JA (2015) Phyllodes tumor diagnosed after ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted excision: should it be followed by surgical excision? Ultrasound Med Biol 41:741–747

Ouyang Q, Li S, Tan C, Zeng Y, Zhu L, Song E et al (2016) Benign phyllodes tumor of the breast diagnosed after ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted biopsy: surgical excision or wait-and-watch? Ann Surg Oncol 23:1129–1134

Park HL, Kwon SH, Chang SY, Huh JY, Kim JY, Shim JY et al (2012) Long-term follow-up result of benign phyllodes tumor of the breast diagnosed and excised by ultrasound-guided vacuum-assisted breast biopsy. J breast cancer 15:224–229

Zurrida S, Bartoli C, Galimberti V, Squicciarini P, Delledonne V, Veronesi P et al (1992) Which therapy for unexpected phyllode tumour of the breast? Eur J Cancer 28:654–657

Kim S, Kim JY (2013) Kim do H, Jung WH, Koo JS. Analysis of phyllodes tumor recurrence according to the histologic grade. Breast Cancer Res Treat 141:353–363

McCarthy E, Kavanagh J, O’Donoghue Y, McCormack E, D’Arcy C, O’Keeffe SA (2014) Phyllodes tumours of the breast: radiological presentation, management and follow-up. Br J Radiol 87:20140239

Barrio AV, Clark BD, Goldberg JI, Hoque LW, Bernik SF, Flynn LW et al (2007) Clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of 293 phyllodes tumors of the breast. Ann Surg Oncol 14:2961–2970

Chaney AW, Pollack A, McNeese MD, Zagars GK, Pisters PW, Pollock RE et al (2000) Primary treatment of cystosarcoma phyllodes of the breast. Cancer 89:1502–1511

Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Balassanian R, Blair SL, Burstein HJ, Cyr A et al (2016) Invasive Breast Cancer Version 1.2016, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw 14:324–354

Douglas-Jones AG, Denson JL, Cox AC, Harries IB, Stevens G (2007) Radial scar lesions of the breast diagnosed by needle core biopsy: analysis of cases containing occult malignancy. J Clin Pathol 60:295–298

Farshid G, Rush G (2004) Assessment of 142 stellate lesions with imaging features suggestive of radial scar discovered during population-based screening for breast cancer. Am J Surg Pathol 28:1626–1631

Fasih T, Jain M, Shrimankar J, Staunton M, Hubbard J, Griffith CD (2005) All radial scars/complex sclerosing lesions seen on breast screening mammograms should be excised. Eur J Surg Oncol 31:1125–1128

Linda A, Zuiani C, Furlan A, Londero V, Girometti R, Machin P et al (2010) Radial scars without atypia diagnosed at imaging-guided needle biopsy: how often is associated malignancy found at subsequent surgical excision, and do mammography and sonography predict which lesions are malignant? Am J Roentgenol 194:1146–1151

Orel SG, Evers K, Yeh IT, Troupin RH (1992) Radial scar with microcalcifications: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiology 183:479–482

Sloane JP, Mayers MM (1993) Carcinoma and atypical hyperplasia in radial scars and complex sclerosing lesions: importance of lesion size and patient age. Histopathology 23:225–231

Berg JC, Visscher DW, Vierkant RA, Pankratz VS, Maloney SD, Lewis JT et al (2008) Breast cancer risk in women with radial scars in benign breast biopsies. Breast Cancer Res Treat 108:167–174

Jacobs TW, Byrne C, Colditz G, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ (1999) Radial scars in benign breast-biopsy specimens and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 340:430–436

Sanders ME, Page DL, Simpson JF, Schuyler PA, Dale Plummer W, Dupont WD (2006) Interdependence of radial scar and proliferative disease with respect to invasive breast carcinoma risk in patients with benign breast biopsies. Cancer 106:1453–1461

Sagara Y, Mallory MA, Wong S, Aydogan F, DeSantis S, Barry WT et al (2015) Survival benefit of breast surgery for low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Surg 150:739–745

Ryser MD, Worni M, Turner EL, Marks JR, Durrett R (2016) Hwang ES. A Computational Risk Analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst, Outcomes of Active Surveillance for Ductal Carcinoma in Situ, p 108

Francis A, Fallowfield L, Rea D (2015) The LORIS Trial: addressing overtreatment of ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin oncol (Royal College of Radiologists (Great Britain)) 27:6–8

Kuerer HM (2015) Ductal carcinoma in situ: treatment or active surveillance? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 15:777–785

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all members of the MIBB working group for their reliable good work entering data for all of their patients who had a VAB. Active breast units entering data in 2015 were: Aarau, Brustzentrum Hirslandenklinik Aarau (B. Saar); Aarau, Kantonsspital Aarau (D. Schwegler-Guggemos); Baden, Kantonsspital Baden (R. Kubik-Huch); Basel, Bethesda-Spital Basel (P. Trabucco); Basel, Brustzentrum Universitätsspital Basel (S. Dellas); Bellinzona, Centro senologico della Svizzera italiana (C. Canonica); Bern, Brustzentrum Bern (M. Sonnenschein); Bern, Inselspital (P. Sager); Bern, Lindenhofspital (S. Gasser); Biel, Spitalzentrum Biel (U. Tesche); Bülach, Spital Bülach (M.L. Kaufmann); Chênes-Bougeries, Clinique des Grangettes (K. Kinkel); Chur, Senologiezentrum, Frauenklinik Fontana (P. Fehr); Frauenfeld, Kantonsspital Frauenfeld (D. Wetter); Genève 4, Hôpital Universitaire de Genève (D. Botsikas); Genève, Imagerie médicale Genève (V. Cerny); Genève, Institut ImageRive (F. Couson); Grabs, Grabs (D. Wruk); Lausanne 20, Imagerie du Flon (D. Lepori); Lausanne, CHUV (J.-Y. Meuwly); Liestal, IMAMED (C. Gückel); Lugano, Centro di Radiologia e Senologia Luganese (G. Kampmann); Lugano, Clinica Sant’Anna (E. Cauzza); Lugano, EOC Lugano (V. A. Vitale); Luzern 16, Kantonsspital Luzern (C. Kurtz); Luzern, Hirslanden-Klinik St. Anna (A. Hoffmann); Schaffhausen, Kantonsspital Schaffhausen (K. Breitling); Schlieren, Verein Brustknotenpunkt (S. Potthast); St. Gallen, Brustzentrum St. Gallen (D. Matt); St. Gallen, Tumor- und Brustzentrum ZeTuP, St. Gallen (V. Dupont Lampert); Thun, Spital STS AG (I. Honnef); Wetzikon, GZO Spital Wetzikon (J. Schneider); Winterthur, Brustzentrum Kantonsspital Winterthur/RIL (Th. Hess); Winterthur, Radiologie am Graben (P. Scherr); Zürich, BrustCentrum Zürich-Bethanien (O. Köchli); Zürich, Brust-Zentrum Zürich Seefeld (C. Rageth); Zürich, Universitätsspital Zürich (D. Fink).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the context of this publication.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rageth, C.J., O’Flynn, E.A., Comstock, C. et al. First International Consensus Conference on lesions of uncertain malignant potential in the breast (B3 lesions). Breast Cancer Res Treat 159, 203–213 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3935-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-016-3935-4