Abstract

Large grazers are known to affect ecosystem functioning even to the degree where ecosystems transition to another vegetation state. Alongside the vegetation change, several features of ecosystem functioning, such as ecosystem carbon sink capacity and soil carbon mineralisation rates, may be altered. It has remained largely uninvestigated how the grazing effects on carbon cycling processes depend on the duration of grazing. Here, we hypothesised that grazing affects ecosystem carbon sink through plant-driven processes (for example, photosynthesis) on shorter time-scales, whereas on longer time-scales changes in soil-driven processes (for example, microbial activity) become more important contributing to a decreased carbon sink capacity. To test this hypothesis, we investigated key processes behind ecosystem carbon cycling in an area that recently had become dominated by graminoids due to a high reindeer grazing intensity and compared these to the processes in an area of decades old grazing-induced graminoid dominance and in an area of shrub dominance with little grazer influence. In contrast to our hypothesis, areas of both old and recent grassification showed a similar carbon sink capacity. Yet the individual fluxes varied depending on the time passed since the vegetation shift: ecosystem respiration and mid-season photosynthesis were higher under old than recent grassification. In contrast, the extracellular enzyme activities for carbon and phosphorus acquisition were similar regardless of the time elapsed since grazer-induced vegetation change. These results provide novel understanding on how ecosystem processes develop over time in response to changes in the intensity of herbivory. Moreover, they indicate that both autotrophic and heterotrophic processes are controlled through multiple drivers that likely change depending on the duration of herbivory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Highlights

-

Reindeer-induced vegetation change affects ecosystem CO2 fluxes with a time-lag

-

Soil C:N ratio and most enzyme activities changed parallel to the vegetation change

-

Grazer control over plant- and soil-driven processes changes with the duration of grazing

Introduction

A line of evidence demonstrates that herbivores are an important component of ecosystem carbon (C) cycling (Hobbs 1996; Augustine and McNaughton 1998; Bardgett and Wardle 2003; Wardle and others 2004) to the extent that their regional effects on C sequestration have been compared to the anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions of different countries (Schmitz and others 2014). By consuming plant biomass and inducing disturbance through trampling, herbivores induce changes in the community composition and overall abundance of vegetation, which reflect on the capacity of ecosystems to fix C (Cahoon and others 2012; Metcalfe and Olofsson 2015). Yet, herbivores also control a range of processes behind ecosystem C release: plant respiration reacts to biomass loss, and microbial activity and C mineralisation processes react to grazer-induced changes in the soil environment (Pastor and others 1996; Olofsson and Oksanen 2002; Stark and others 2007). Ultimately, herbivory-induced changes in C uptake and release equal to amount the C sink capacity of the ecosystem, referred to as net ecosystem exchange (NEE). These effects may range from neutral to positive and negative (Schmitz and others 2014).

A wide array of herbivory impacts on C cycling act through changes in soil nutrient cycles and altered soil properties. These are indirectly modified by vegetation changes that alter plant water uptake and albedo, as well as the quantity and quality of plant litter and exudates entering the decomposer subsystem (Olofsson and others 2004; Haynes and others 2014; te Beest and others 2016). Additionally, through the trampling of soil and the deposition of urine and faeces, herbivores compact the soil, provide patches of increased nutrient availability (Sirotnak and Huntly 2000; van der Wal and Brooker 2004; Barthelemy and others 2015) and relocate nutrients from the feeding to the resting places of herbivores (Abbas and others 2012; Stark and others 2015a; Sitters and others 2017). These changes may be substantial, and for example the impact of herbivory on soil temperatures and nutrient availability may even exceed the projected, global warming-induced changes (Olofsson and others 2004; Stark and others 2015b). In some cases, the changes result in a positive effect of herbivory on plant productivity and soil nitrogen (N) availability (Andriuzzi and Wall 2017) with consequences for soil nutrient stoichiometry and phosphorus (P) availability (Stark and Väisänen 2014; Sitters and others 2017). As nutrient availability is a strong determinant for both plant productivity, that is, C uptake by vegetation, and soil microbial activity in tundra (Weintraub and Schimel 2003; Schimel and Bennett 2004), grazing-induced changes in soil N cycling could feedback on ecosystem C cycling. Yet, in other cases, herbivory exerts the exact opposite effect and decreases productivity and nutrient cycling (Bardgett and Wardle 2003). Regardless of the direction of the herbivore effect, this may promote a vegetation shift into a different vegetation type (Bardgett and Wardle 2003; van der Wal 2006; Zimov and others 2012). When this takes place, the grazing effect on both C uptake and release may become independent of the actual grazing event and instead be driven by long-term changes in vegetation and soil C quality (Stark and Väisänen 2014).

Although the grazing-induced ecosystem consequences are well known, we still lack understanding on how the relative magnitude of the different cascading herbivore effects varies in time during a grazer-induced shift in vegetation. Contrasting with the direct effects of herbivory, the indirect soil feedbacks could act with different response times, be of transient or slow nature and they may accelerate or stabilise the rapid herbivory effects. Eventually, the effects of herbivory in decadal time-scales could be both quantitatively and qualitatively different from the short-term effects (that is, the first 5–10 years), because they derive from different mechanisms (Väisänen and others 2014). Within the first years, herbivore-induced changes in gross ecosystem production (GEP) might dominate the net effect of herbivory on NEE (as in Cahoon and others 2012; Metcalfe and Olofsson 2015), whereas on longer time-scales, the indirect changes in nutrient availability and soil microbial activity could become more important.

Here, we investigated the time scale of different grazing impacts on sub-arctic tundra ecosystem by comparing ecosystem processes among a shrub-dominated lightly grazed tundra and two areas with different-aged grazer-induced vegetation shifts (> 60 years and < 15 years). We used a reindeer pasture rotation fence in northern Norway, along which a yearly grazing pulse by reindeer (Rangifer tarandus L.) has replaced shrub-dominated tundra with graminoids (Olofsson and others 2001, 2004) over 60 years ago. Parallel to the grassification of vegetation, soil nutrient availability, microbial activity for C cycling (Olofsson and Oksanen 2002; Stark and others 2002; Olofsson and others 2004; Stark and Väisänen 2014), and ecosystem respiration had increased leading to a weaker net ecosystem C sink (that is, less negative NEE; Väisänen and others 2014). These changes have been detected decades after the change in grazing pressure. Now, we monitored ecosystem processes also in a third area, which was still dominated by shrubs 14 years earlier (Olofsson and others 2001, 2004), but has since gained dominance of graminoids (Ylänne and others 2018). The comparison of zones with decadal old graminoid dominance (Olofsson and others 2001), recent graminoid dominance (Ylänne and others 2018) and a control zone dominated by shrubs with decadal history of little reindeer influence provided unique means for investigating how grazer-induced shifts in the vegetation and soil processes contribute to the grazing effect on the C sink.

We quantified growing season C sink (NEE), photosynthesis (GEP), ecosystem respiration, C:N ratios of different ecosystem compartments, and soil microbial activities for C cycling. We expected that the plant-driven processes (that is, GEP) would represent more rapid responses to grazer-induced changes in vegetation, whereas the soil-driven processes (that is, microbial activities) would represent slow responses. More specifically, we hypothesised that ecosystem C uptake (GEP) would be similar in both graminoid-dominated areas and thereby not depend on the time since vegetation change. However, in terms of the soil microbial activity for C cycling, we hypothesised that the old vegetation type would control differences in soil C quality, and therefore, that soil C:N ratio and soil microbial activities under recent grassification would still be similar to those under shrub dominance. Furthermore, although ecosystem respiration is a result of both autotrophic and heterotrophic respiration, we expected it to follow the same trend as soil microbial activity and be lower under shrub dominance and recent grassification than under old grassification. Finally, this temporal discrepancy in grazer effects on plant-driven and soil-driven processes was expected to result in a higher net ecosystem C sink (that is, more negative NEE) under recent grassification than under old grassification.

Materials and Methods

Study Area and Experimental Set-Up

This study was conducted in Raisduoddar, northern Norway, approximately 100 m above the treeline (69°31′29 N, 21°19′16 E; altitude 430–570 m a.s.l.), where the dominant vegetation is of the Empetrum–Dicranum–Lichens type (Oksanen and Virtanen 1995). A reindeer pasture rotation fence built in the 1960s bisects the site separating the coastal summer ranges from the autumn, spring and winter ranges further inland. During late summer, reindeer start to migrate towards their autumn range, but they become halted by the fence, since it is not legal to enter autumn ranges at the time. This results in reindeer staying at one side of the fence for approximately 2–3 weeks. As a consequence, the summer range side of the fence is heavily grazed and trampled, which has resulted in graminoids gaining dominance over bryophytes, lichen and the deciduous and evergreen shrubs (Olofsson and others 2001). In contrary, the autumn–spring range near the fence is only sporadically used during the spring and autumn migrations, and the vegetation consists of both deciduous and evergreen shrubs underlain by a thick bryophyte layer (Olofsson and others 2001). Previously, the reindeer-induced vegetation transition had been limited to the immediate vicinity of the fence (Olofsson and others 2001) resulting from the tendency of reindeer to follow fences. However, between the years 2002 and 2014, the vegetation further away from the fence had gained graminoid dominance (Ylänne and others 2018).

To compare the ecosystem processes under recent and decades old grassification, we used eight geologically and topographically homogenous transects that bisected the reindeer fence 100 m apart from each other (Olofsson and others 2004; Ylänne and others 2018). The shrub-dominated control zone (LG) located approximately 10 m from the fence on the autumn-spring range, the zone with decades old reindeer-induced grassification (HG) located 10 m from the fence on the summer range, and the zone with recent reindeer-induced grassification (MG; Ylänne and others 2018) located 100 m from the fence in the summer range. Here, we refer to the zones with the same acronyms that have been used for the site before, where the letters denote the previous intensity of grazing (low, high, moderate). Notably, in the year of this study, 2014, reindeer activity analysed with trampling indicators did not differ between MG and HG (Ylänne and others 2018) although in 2000, it had been approximately 30% higher in HG than MG (Olofsson and others 2004). One plot of 1 × 1 m was set to each zone along the eight transects yielding 24 study plots.

Prevalent Vegetation and C:N Ratios in Different Ecosystem Compartments

In 2014, at the time of the reported results, graminoids and forbs were the dominant plant group in HG, whereas vegetation in LG was characterised by a mosaic of evergreen and deciduous dwarf shrubs underlain by a thick moss carpet (Ylänne and others 2018). In MG, graminoids had gained dominance and replaced the deciduous shrubs and bryophytes prevalent in 2000 (Olofsson and others 2001, 2004); yet, patches of evergreen shrubs persist in the area (Ylänne and others 2018). As a result of grazing, in both HG and MG, the abundance and height of deciduous shrubs was similarly low (Figure 1, Supplementary table S1) the cover and depth of the bryophyte layer was lower and the cover of litter was higher when compared to LG. Also graminoid abundance was similar in MG and HG, yet, graminoids grew taller in HG than MG (Figure 1). There were more evergreen dwarf shrubs in MG than HG, but no difference in the abundance and height of the dominant evergreen dwarf shrub species, Empetrum nigrum ssp. hermaphroditum.

The average abundance (left) and height (right) of graminoids, deciduous shrubs, evergreen shrubs, bryophytes and the litter layer in the three grazing zones. The values represent mean ± 95% confidence intervals in different grazing zones (LG = light grazing, MG = recent grazer-induced grassification, HG = old grazer-induced grassification). The letters above the charts denote the significant differences among grazing zones as identified by Least Squares comparison. The abundance was measured as hits 40 pins−1 during the peak growing season (July 18th–19th, 2014). From vascular vegetation, all hits were recorded, whereas from the ground layer (that is, bryophytes and lichens) only the first hit for each species. The maximum height of graminoids, Betula nana and Empetrum nigrum ssp. hermaphroditum represents the average height of the five tallest individuals. The average depth of bryophyte and litter layers is derived from five measurements placed randomly on the study plots. Data partly redrawn from Ylänne and others (2018).

To assess the C:N ratio in different ecosystem compartments, we collected biomass samples from aboveground and belowground vascular vegetation as well as the litter layer. All aboveground vascular vegetation was clipped from an area of 50 × 50 cm and divided to growth forms (for example, evergreen shrubs, deciduous shrubs, graminoids and forbs) and subsequently, dried, weighed, milled (25 revs s−1 for 20 s, Retsch MM301 mill) and analysed for C:N ratio with a CHNS–O Elemental analyser (EA1110, CE Instruments). We used two intact vegetation-soil cores (Ø 11.95 cm) to obtain litter biomass and 5–10 soil cores (Ø 2.9 cm) per plot to obtain vascular belowground biomass. Litter was hand picked from the cores, whereas the vascular belowground biomass was washed from soil remains (sieve mesh 0.5 mm). Samples from both compartments were dried, weighed and milled for the C:N analysis.

Field-Layer Carbon Dioxide Flux

We analysed net ecosystem C exchange (NEE), gross ecosystem productivity (GEP) and ecosystem respiration (ER) using a closed system composed of a custom-built acrylic chamber (Ø 30 cm, 39 cm height) coupled with a Vaisala carbon dioxide probe (GMP343), a Vaisala humidity and temperature probe (HMP75), a Vaisala Measurement Indicator (MI70) and a quantum-photo-radiometer (HD 9021). The measurements were conducted within 3 h of midday on five occasions during the growing season of 2014 (June 12, June 24, July 16, August 2 and August 30). Each transect was measured at the same time by seven consecutive measurements at each plot; four with gradually decreasing light intensity (ambient light, 35%, 50% and 65% shading) and three in the dark to account for ecosystem respiration (ER). Between each measurement, the chamber was vented to allow the CO2 concentration to return to ambient. The gradual shading was implemented with hoods made of single-, double- and triple-layer white mosquito nets and the dark measurements were obtained by covering the chambers with an opaque white hood that did not permit light to the plots. We logged the CO2 concentration, temperature and humidity inside the chambers at 5 s intervals for 90 s, during which photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) within the chamber was monitored. The CO2 flux was corrected for changes in the water vapour pressure (Hooper and others 2002) with the following formula:

where Cb and Cf are the CO2 concentrations at the beginning and end of measuring period, respectively (µmol CO2 mol−1 air), Pb and Pf are the atmospheric pressures at beginning and end of measuring period, respectively (mb), Tb and Tf are the temperatures (°C) at beginning and end of measuring period, respectively, V is the volume of the system (ml), t is the elapsed time (s) and s is the surface area (m2). The fluxes are shown as µmol CO2 m−2 s−1 and NEE is presented from the atmospheric perspective (that is, a negative flux indicates net CO2 uptake by the ecosystem).

We counted GEP as NEE–ER and standardised it to a common irradiance (PAR = 600 µmol m−2 s−1) based on light-response curves generated for every plot during each occasion to fit a Michaelis–Menten model (Ritz and others 2015). Due to the small number of measurements, we used the raw CO2 flux data in the statistical analysis and accounted for the random effects of temperature for ER and irradiance for NEE and GEP. We also present the light-standardised values (GEP600, NEE600) and use these to calculate average daytime flux rates over the growing season as weighted means for the period June 1st–September 15th. Weighed means were obtained by plotting the fluxes against the measurement days and deriving an estimate for each day by local polynomial regression fitting (R Core Team 2012). This procedure takes into account uneven intervals between the CO2 measurements.

Microbial Respiration, Enzyme Activities and Their Temperature Sensitivity in the Organic Soil Layer

To depict microbial potential for soil C and nutrient cycling, we analysed microbial respiration (that is, the release of CO2 from the soil) and the activities of key extracellular enzymes responsible for soil C degradation. We collected soil samples on three sampling dates (June 11th, June 25th and July 19th) with 5–10 soil cores (Ø 2.9 cm) extending the entire soil organic layer (average depth = 4.35 ± 0.30). The depth of each sample was recorded, and the samples were subsequently combined to form one composite sample per plot. The samples were sieved (2 mm mesh) in the laboratory, stored in 4 °C and analysed within a week of sampling. For background information, we analysed soil moisture (105 °C, 12 h), organic matter content (loss on ignition at 475 °C, 4 h) and bulk density (dry weight of soil per sample volume) from the sieved samples. Soil ammonium (NH4+–N) was extracted with 0.5 M K2SO4 and analysed colorimetrically (SFS 3032, Shimadzu UV-1700 spectrophotometer). We did not analyse soil nitrate (NO3−–N) concentrations as previous investigations at the same site had shown very low concentrations (for example, Stark and others 2002) indicating a minor importance in the N cycle.

Microbial respiration was analysed to depict the rate of C release from soil organic matter. At the site, soil temperatures differ depending on grazing, being highest in HG, and higher in MG than LG (Ylänne and others 2018), with further feedbacks on the temperature sensitivity of the soil microbial activity (Stark and others 2015b). For this reason, we analysed soil microbial activities at a range of temperatures. Soil CO2 release (microbial respiration) and its temperature sensitivity were analysed by incubating fresh soil samples in 100 ml incubation bottles sealed with rubber stoppers at four temperatures (4, 9, 14 and 19 °C). The bottles were pre-incubated for 48 h and aired before the actual incubation time of 72 h. We collected airsamples from the headspace of the bottles and analysed those for the concentration of microbially released CO2 with a gas chromatograph (HP 6890). The microbial respiration is reported as mg CO2 g OM−1 h−1.

Further, we analysed the potential activities of three hydrolytic extracellular enzymes that catalyse the degradation of soil C: β-glucosidase (BG) that releases glucose from cellulose, β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAG) that hydrolyses N-acetyl glucosamine residues from chitin-derived oligomers, and acid-phosphatase (AP) that catalyses the release of phosphate by hydrolysing the phosphoric ester bonds of phosphate groups in organic molecules. BG can be regarded a proxy for C turnover, AP for P acquisition, and NAG for N acquisition through the breakdown of fungal derived chitin (Sinsabaugh and others 2008). The potential activities were extracted with the corresponding chromogenic substrates (Boerner and others 2000): 5 mmol paranitrophenyl(pNP)-β-glucopyranoside for BG, 3 mmol pNP-β-N-acetylglucosaminide for NAG, and 5 mmol pNP-phosphate for AP. We conducted all assays in sodium acetate buffer (50 mM) that corresponds to the study site soil pH (5.0), and incubated the samples at four temperatures (4, 9, 14 and 19 °C). Following the incubations, the samples were centrifuged, after which we transferred 100 ml of the supernatant into a 96-well plate; added 5 ml of 1.0 M NaOH, and analysed the absorbance at 410 nm using a Multiscan FC microplate reader (Thermo Scientific). We corrected the assay absorbance to account for homogenate and substrate absorbance by subtracting those. We used standard curves for paranitrophenol to calculate the extinction coefficients for the potential activities and reported those as μmol h−1 g OM−1.

We calculated the temperature sensitivity (Q10) of microbial respiration and enzyme activities by plotting the natural logarithm of CO2-C release/activity against the incubation temperature and using the slope (k) of the linear regression in the following formula: Q10 = e(10 × k) (for example, Wallenstein and others 2009).

Statistical Analyses

We tested for the effects of measurement time, grazing and their interaction on the ecosystem processes with a repeated measures mixed effects model (Pinheiro and others 2014). For GEP600 and NEE600 and the Q10 values of microbial respiration and enzyme activities, measurement time, grazing and their interaction were set as fixed factors and transect was kept as a random factor. For microbial respiration and enzyme activities, we also included the incubation temperature and its interactions to the fixed factors. We used the same test without the repeated measures design for the growing seasonal weighed averages of CO2 fluxes. In all models, the pairwise differences between grazing intensities were subsequently tested with the least squares means post hoc test (Lenth 2016).

For ecosystem CO2 fluxes, we used the lme4 package (Bates and others 2015), where also the random effect of temperature (for ER) or PAR (for GEP and NEE) were included in the models. We used Satterthwaite approximation to estimate the degrees of freedom (Kuznetsova and others 2016) and tested the pairwise differences between grazing intensities on each measurement occasion with the least squares means post hoc test. All data processing and statistical analyses were performed with R software for statistical computing (R Core Team 2012) and the package ggplot2 (Wickham 2009) was used for drawing the figures.

Results

Grazing Effects on Ecosystems C:N Ratios

The C:N ratios in the above- and belowground biomass of vascular vegetation were highest in the shrub-dominated LG and did not differ between HG and MG (Figure 2, Table 1). Grazing had similarly decreased the C:N ratio in litter. However, litter C:N ratio was even lower on HG than on MG. Similarly, grazing had increased NH4+-N in organic soil in both HG and MG, so that the C:N ratios of HG and MG were significantly lower than that of LG (Table 1; data from Ylänne and others 2018).

Carbon-to-nitrogen ratios in aboveground vascular vegetation, belowground vascular vegetation, litter, organic soil and mineral soil. The values display average C:N ratio (%) with a 95% confidence interval in different grazing zones (LG = light grazing, MG = recent grazer-induced grassification, HG = old grazer-induced grassification). The letters above the charts denote the significant differences among grazing zones as identified by Least Squares comparison. Organic and mineral soil C:N ratios drawn after Ylänne and others (2018).

Ecosystem CO2 Fluxes

We found no significant grazing effect on the growing seasonal average fluxes of light-standardised ecosystem productivity (GEP600-wm) and respiration (ER; Table 1; Figure 3). Yet, the weighed mean of NEE600 was indicatively less negative in HG and MG than LG (P = 0.070), indicating a lower CO2 sink potential in both graminoid-dominated areas compared to the shrub-dominated LG.

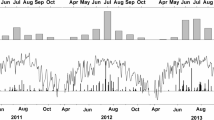

Ecosystem–atmosphere CO2 fluxes in different grazing zones. Left panel represents the raw values of GEP, ER and NEE on the measurement occasions during the growing season of 2014. The right panel represents the weighed means of GEP600, ER and NEE600. The values display mean with a 95% confidence interval in different grazing zones (dark green = light grazing, light green = recent grazer-induced grassification, orange = old grazer-induced grassification). The letters above the charts denote the significant differences among grazing zones as identified by Least Squares comparison. On the left panel, the significant differences are shown separately at each measurement occasion (Color figure online).

Despite similarities in the average values of GEP and ER, seasonal differences among the grazing zones were found (see pairwise differences in Table S2 in the Supplementary material). More often, ecosystem respiration was higher in HG than in LG and MG (Table 2; Figure 3). In the beginning of the growing season, all CO2 fluxes were similar among the grazing zones. Towards mid-July, ecosystem respiration and gross ecosystem production were both higher on HG than on LG or MG. Yet, when looking at NEE, both HG and MG functioned as a stronger CO2 sink than LG. In the beginning of August, both graminoid-dominated areas, HG and MG, had higher ecosystem respiration when compared to LG with no significant difference among the grazing intensities in NEE. After the reindeer grazing pulse, the gross ecosystem productivity dropped in both HG and MG, being significantly lower than in LG. In MG, also ecosystem respiration decreased notably after grazing, whereas in HG, ecosystem respiration remained high. As a result, ecosystem respiration was lower in MG than HG and LG. Despite the differences in ecosystem respiration, NEE in August did not differ significantly between HG and MG, although both areas functioned as weaker CO2 sinks than LG.

Microbial Activity

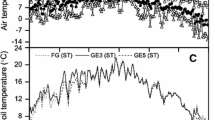

The seasonal development of soil microbial activity was opposite to the seasonal trend in plant activity. Microbial respiration and the potential activities of B-glucosidase (BG) and N-acetyl-glucosane (NAG) in the organic soil layer were the highest in the beginning of the growing season, and became smaller towards the mid of growing season (Figure 4 and Supplementary figure 1). Yet, the potential activity of acid-phosphatase (AP) increased with the advance of the summer (Figure 4), alike the temperature sensitivities (Q10) of microbial respiration and BG and NAG activities (Figure 4).

Microbial respiration and the potential activities of B-glucosidase (BG), acid-phosphatase (AP) and N-acetyl-glucosane (NAG) at 9 °C (left) and their temperature sensitivities (right) on the three measurement occasions in 2014. The values represent mean ± 95% confidence intervals in different zones (dark green = light grazing, light green = recent grazer-induced grassification, orange = old grazer-induced grassification). The letters above the charts mark the significant differences among grazing intensities across all measurement dates (Color figure online).

Microbial activities and their temperature sensitivities varied depending on grazing irrespective of the measurement time (Tables 3 and 4). Microbial respiration was higher in LG than HG (Table 3), and NAG activity followed the same pattern tentatively, although the grazing effect was not statistically significant (P = 0.057). Notably, microbial respiration or NAG activity in MG did not differ significantly from that in LG. In contrast to NAG and microbial respiration, the potential activities of BG and AP were higher in the graminoid-dominated MG and HG when compared to LG (Table 3). Yet their temperature sensitivities were highest in LG (Table 4). The temperature sensitivity (Q10) of NAG was higher in HG than in LG and there was no difference in the temperature sensitivity of microbial respiration among the grazing intensities (Figure 4; Table 4).

Discussion

In this paper, we quantified how C cycling under recent grazer-induced grassification relates to C cycling under an area with a long history of graminoid dominance and on a shrub tundra with low reindeer influence. We expected both old and recent graminoid-dominated areas to maintain similar rates of gross ecosystem productivity (GEP), whereas we expected the soil microbial activities for C cycling and ecosystem respiration under recent grassification to be more similar to those under shrub dominance, resulting in a higher C sink capacity. In contrast to our expectations, we found that the net ecosystem exchange (NEE) over the growing season did not differ between old and recent grassification, but it was tentatively less negative in both graminoid-dominated areas than under shrub dominance. Yet, the duration of grazing altered the processes governing the NEE, as the seasonal trends of both ecosystem respiration and the mid-season photosynthesis differed between old and recent grassification. Interestingly, these temporal differences balanced each other and led to a similar outcome on the C sink. Likewise, contrasting our expectations, we observed both similarities and differences in the soil processes between the graminoid-dominated areas: the potential enzymatic activities of BG and AP were higher on both graminoid-dominated zones than under shrub dominance whereas the potential activity of NAG was the same under recent grassification as under shrub dominance. Put together, our results revealed that different ecosystem processes respond to herbivory with different time-scales and indicate that both autotrophic and heterotrophic processes are controlled through multiple drivers that vary depending on the herbivory history.

Grazing Effect on Ecosystem Respiration and Photosynthesis Depended on the Age of Vegetation Shift

Our results revealed that the impact of grazing-induced grassification on ecosystem CO2 sink was similar irrespective of the age of the vegetation shift: in both grazed areas, grazing contributed to a tentatively less negative NEE when compared to the adjacent area with shrub dominance. Grazing effects on C sink were particularly obvious on two occasions: in the middle of the growing season, when grazed areas functioned as stronger CO2 sinks, and after the yearly grazing event, when the CO2 sink in HG and MG had decreased. Noteworthy, the decrease in CO2 sink during late growing season dominated the grazing effect on the growing seasonal average NEE (as in Väisänen and others 2014, Supplementary material).

Even though the age of the vegetation shift did not alter the grazing effect on CO2 sink, the seasonal differences in C uptake and release varied depending on the duration of grazing. More commonly, we found higher ecosystem respiration and mid-season photosynthesis under old than recent grassification, which indicates that the higher respiration under graminoid dominance evolves with time. Yet, we also found that, by the end of the growing season, grazing-induced decrease in productivity contributed to the grazing effect on the CO2 sink. In both graminoid-dominated areas, GEP dropped after the grazing pulse leading to a decreased CO2 sink strength, which likely depicts the immediate effect of plant consumption on GEP (Cahoon and others 2012; Metcalfe and Olofsson 2015). Under recent grassification, ecosystem respiration decreased at the same time, whereas under old grassification, respiration rates remained high even after the grazing pulse. The continuously high ecosystem respiration under the old graminoid dominance indicates that respiration was not solely a function of autotrophic processes. As microbial respiration in the organic soil layer was the same under both recent and old grassification, we suggest that the differences in ecosystem respiration in response to grazing likely derived from microbial respiration in the litter layer.

The Age of Vegetation Shift had Divergent Influence on Soil Microbial Activities

Contrasting with our hypotheses, the differences among grazing regimes in soil processes were not uniform: microbial respiration and the potential activities of BG and AP were the same under both recent and old grassification, whereas NAG activity was as high under recent grassification as under shrub dominance. These results demonstrate that the indirect effects of herbivory on the different soil microbial processes may have largely differing response times and be jointly governed by the stoichiometric C and nutrient demand of microbes as well as the substrate availability (Wallenstein and others 2009; Koyama and others 2013; Sistla and others 2014; Stark and others 2015a). As soil microorganisms synthesise enzymes to meet their own resource requirement, the high N availability in the grazed areas could downregulate the activities for N acquisition (Sinsabaugh and others 2008; Sinsabaugh and Follstad Shah 2012). Here, we found higher NAG activity under recent than old grassification although the organic soil C:N ratio or mineral N availability did not differ between the graminoid-dominated areas. We suggest the higher NAG activity to be induced by higher fungal biomass and thus, higher levels of chitin in the soil (Hernández and Hobbie 2010; Kielak and others 2013; Zeglin and others 2013). As chitin supply mainly controls chitin degradation (Beier and Bertilsson 2013), a delayed shift of the soil microbes from chitin-containing fungi to bacteria after the vegetation change could likely explain the slow response time of NAG activity to grazer-induced change in vegetation and soil N availability.

In contrast to NAG activity, the potential activities of BG and AP were similar in MG and HG, being significantly higher than the activities in LG. According to the theory of stoichiometric regulation of enzyme activities, enhanced BG activity could result from the grazer-induced increase in soil N; and reflect a higher microbial demand for C (Sinsabaugh and others 2008). However, a previous investigation at the study site showed that BG activity did not respond to increased N availability connected with the reindeer grazing pulse (Stark and Väisänen 2014) indicating that microbial saturation of N is likely not the main driver behind BG activity. Instead, the higher BG activity under graminoid dominance could derive from altered substrate availability (Stark and Väisänen 2014) as graminoid litter contains labile compounds that are rapidly degraded by soil microorganisms (De Deyn and others 2008). On the other hand, the higher AP activity in graminoid-dominated areas could derive from the microbial stoichiometric demand, and demonstrate the tendency of soil microorganisms to allocate more resources for P mineralisation to balance changes in the soil N:P stoichiometry (Stark and Väisänen 2014; Sitters and others 2017). These results are in line with the general observation that microbial enzyme activities are closely governed by the soil N:P stoichiometry, whereas the relationship between enzyme activities and soil C:N stoichiometry is not equally clear (Sinsabaugh and Follstad Shah 2012).

Interestingly, soil NH4-concentrations further away from the pasture rotation fence increased even before vegetation grassification (38, 78 and 87 µg m−2 in 2000 in LG, MG and HG, respectively; Olofsson and others 2004). Thus, many of the soil-driven processes may have changed even before graminoids gained dominance in the vegetation as a response to the combined effects of increased N availability and the gradual change in vegetation. We suggest that one of the triggering forces for the ecosystem shift could have been the decline in bryophytes. Notably, in 2000, the bryophyte biomass was equally high in both MG and LG (99 ± 36 g, and 97 ± 42 g, compared to the lower biomass, 19 ± 11 g, in HG), whereas in 2014, there was no difference in bryophyte biomass between HG and MG (Ylänne and others 2018). It has been shown that bryophytes may trap nutrients from urine and thereby prevent nutrient enrichment in the soil (Barthelemy and others 2018). Thus, a gradual decline of the bryophyte layer could permit higher nutrient availability into the soils and, through the loss of insulation, alter soil physical environment and increase soil temperatures. These mechanisms may have enhanced soil decomposition rates and—in combination with the trampling-induced disturbance to the deciduous and evergreen shrubs—opened up a window of opportunity for graminoids to increase in abundance.

Implications for Understanding the Temporal Dynamics of Grazer-Induced Ecosystem Changes

In this paper, we showed that the effect of grazing on ecosystem C sink was similar regardless of the time passed since the vegetation state shift. Yet, the time passed after graminoids gained dominance affected which processes governed the grazing effect on the C sink (Figure 5). We found that high rates of photosynthesis evolve with time after graminoid dominance as mid-season GEP was not as high under recent than old grassification (< 12 years vs > 60 years). Yet, this difference was not reflected on the ecosystem C sink as the mid-season ecosystem respiration was also lower under recent graminoid dominance. We also found that the grazing-induced changes in soil processes varied depending on the duration of grazing. The activities of BG and AP under recent grassification were already the same as under old grassification, and in contrast, NAG activity was still as high as under the shrub dominance. The differences in microbial activities suggest a rapid response of microbes to the changed litter quality and N:P stoichiometry, and at the same time, a possibly high chitin availability as a legacy of the old vegetation.

Taken together, our findings confirmed the initial hypothesis that the different processes influenced by herbivory have different response times, and revealed unexpected variation within the plant- and soil-driven processes. Still, this data should not be generalised to represent long- and short-term effects of grazing on the C sink across the tundra, as a vegetation shift alike the described one is unlike to take place across all grazed sites. Indeed, previous studies report that there are no consistent vegetation trends caused by reindeer grazing (Bernes and others 2015) and indicate that, at the landscape level, grazing-induced increase in evergreen vegetation may be more common than the increase in graminoids (Bråthen and others 2007). As evergreen shrubs have low rates of litter fall and high concentrations of phenolic compounds in their tissues, the consequences of grazer-induced increase in evergreens for decomposition and nutrient availability are not the same as in cases where grazing increases graminoid dominance (Ylänne and others 2015). Furthermore, even in cases when grazing promotes a higher abundance of graminoids, nutrient availability might not necessarily increase (Haynes and others 2014; Ricca and others 2016) and the consequences for soil C cycling might depend on the initial vegetation type (Ylänne and others 2018).

Our results are, however, consistent with earlier studies showing that the long-term, for example, decadal, effects of grazing on both vegetation (Saccone and Virtanen 2016) and the ecosystem C sink (Väisänen and others 2014) differ from the initial effects within a timeframe of a couple of years. This highlights that process rates in any given time, may only present a time window of processes under a constant change driven by herbivory. We believe this to be irrespective of the type of vegetation change induced by herbivory. Partly, the timeframe of change could also constitute one of the factors explaining the bidirectional grazing effects on productivity and soil C and nutrient cycling in different ecosystems (sensu Wardle and others 2004). How the different ecosystem processes change along with the duration of herbivory should therefore be incorporated into the general theoretical framework describing the role of herbivory in ecosystems.

References

Abbas F, Merlet J, Morellet N, Verheyden H, Hewison AJM, Cargnelutti B, Angibault JM, Picot D, Rames JL, Lourtet B, Aulagnier S, Daufresne T. 2012. Roe deer may markedly alter forest nitrogen and phosphorus budgets across Europe. Oikos 121:1271–8.

Andriuzzi WS, Wall DH. 2017. Responses of belowground communities to large aboveground herbivores: Meta-analysis reveals biome-dependent patterns and critical research gaps. Global Change Biology 23:3857–68.

Augustine DJ, McNaughton SJ. 1998. Ungulate Effects on the Functional Species Composition of Plant Communities: Herbivore Selectivity and Plant Tolerance. Journal of Wildlife Management 62:1165–83.

Bardgett RD, Wardle DA. 2003. Herbivore-mediated linkages between aboveground and belowground communities. Ecology 84:2258–68.

Barthelemy H, Stark S, Michelsen A, Olofsson J. 2018. Urine is an important nitrogen source for plants irrespective of vegetation composition in an Arctic tundra: Insights from a 15N-enriched urea tracer experiment. Journal of Ecology 106:367–78.

Barthelemy H, Stark S, Olofsson J. 2015. Strong responses of subarctic plant communities to long-term reindeer feces manipulation. Ecosystems 18:740–51.

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2015. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67:1–48.

te Beest M, Sitters J, Ménard CB, Olofsson J. 2016. Reindeer grazing increases summer albedo by reducing shrub abundance in Arctic tundra. Environmental Research Letterst 11:125013.

Beier S, Bertilsson S. 2013. Bacterial chitin degradation-mechanisms and ecophysiological strategies. Frontiers in Microbiology 4:1–12.

Bernes C, Bråthen KA, Forbes BC, Hofgaard A, Moen J, Speed JD. 2015. What are the impacts of reindeer/caribou (Rangifer tarandus L.) on arctic and alpine vegetation? A systematic review protocol. Environmental Evidence 2:6.

Boerner REJ, Decker KLM, Sutherland EK. 2000. Prescribed burning effects on soil enzyme activity in a southern Ohio hardwood forest: a landscape-scale analysis. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 32:899–908.

Bråthen KA, Ims RA, Yoccoz NG, Fauchald P, Tveraa T, Hausner VH. 2007. Induced shift in ecosystem productivity? Extensive scale effects of abundant large herbivores. Ecosystems 10:773–89.

Cahoon SMP, Sullivan PF, Post E, Welker JM. 2012. Large herbivores limit CO2 uptake and suppress carbon cycle responses to warming in West Greenland. Global Change Biology 18:469–79.

De Deyn GB, Cornelissen JHC, Bardgett RD. 2008. Plant functional traits and soil carbon sequestration in contrasting biomes. Ecology Letters 11:516–31.

Haynes AG, Schütz M, Buchmann N, Page-Dumroese DS, Busse MD, Risch AC. 2014. Linkages between grazing history and herbivore exclusion on decomposition rates in mineral soils of subalpine grasslands. Plant and Soil 374:579–91.

Hernández DL, Hobbie SE. 2010. The effects of substrate composition, quantity, and diversity on microbial activity. Plant and Soil 335:397–411.

Hobbs NT. 1996. Modification of Ecosystems by Ungulates. Journal of Wildlife Management 60:695–713.

Hooper DU, Cardon ZG, Chapin FS, Durant M. 2002. Corrected calculations for soil and ecosystem measurements of CO2 flux using the LI-COR 6200 portable photosynthesis system. Oecologia 132:1–11.

Kielak AM, Cretoiu MS, Semenov AV, Sørensen SJ, Van Elsas JD. 2013. Bacterial chitinolytic communities respond to chitin and pH alteration in soil. Applied Environmental Microbiology 79:263–72.

Koyama A, Wallenstein MD, Simpson RT, Moore JC. 2013. Carbon-Degrading Enzyme Activities Stimulated by Increased Nutrient Availability in Arctic Tundra Soils. PLoS One 8:e77212.

Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff P, Christensen R. 2016. lmerTest: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. R Package version 3.0.0. https://cran.r-project.org/package=lmerTest

Lenth RV. 2016. Least-Squares Means: The R Package lsmeans. Journal of Statistical Software 69:1–33.

Metcalfe DB, Olofsson J. 2015. Distinct impacts of different mammalian herbivore assemblages on arctic tundra CO2 exchange during the peak of the growing season. Oikos 124:1632–8.

Oksanen L, Virtanen R. 1995. Topographic, altitudinal and regional patterns in continental and suboceanic heath vegetation of northern Fennoscandia. Acta Botanica Fennica 153:1–80.

Olofsson J, Kitti H, Rautiainen P, Stark S, Oksanen L. 2001. Effects of summer grazing by reindeer on composition of vegetation, productivity and nitrogen cycling. Ecography 24:13–24.

Olofsson J, Oksanen L. 2002. Role of litter decomposition for the increased primary production in areas heavily grazed by reindeer: a litterbag experiment. Oikos 96:507–15.

Olofsson J, Stark S, Oksanen L. 2004. Reindeer infuence on ecosystem processes in the tundra. Oikos 2:386–96.

Pastor J, Dewey B, Christian DP. 1996. Carbon and nutrient mineralization and fungal spore composition of fecal pellets from voles in Minnesota. Ecography 19:52–61.

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team. 2014. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R Package version 31-118. http://cran.r-project.org/package=nlme

R Core Team. 2012. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. http://www.r-project.org/

Ricca MA, Miles AK, Van Vuren DH, Eviner VT. 2016. Impacts of introduced rangifer on ecosystem processes of maritime tundra on subarctic islands. Ecosphere 7:1–23.

Ritz C, Baty F, Strebig JC, Gerhard D. 2015. Dose-Response Analysis Using R. PLoS One 10:e0146021.

Saccone P, Virtanen R. 2016. Extrapolating multi-decadal plant community changes based on medium-term experiments can be risky: Evidence from high-latitude tundra. Oikos 125:76–85.

Schimel JP, Bennett J. 2004. Nitrogen mineralization: Challenges of a changing paradigm. Ecology 85:591–602.

Schmitz OJ, Raymond PA, Estes JA, Kurz WA, Holtgrieve GW, Ritchie ME, Schindler DE, Spivak AC, Wilson RW, Bradford MA, Christensen V, Deegan L, Smetacek V, Vanni MJ, Wilmers CC. 2014. Animating the carbon cycle. Ecosystems 17:344–59.

Sinsabaugh RL, Follstad Shah JJ. 2012. Ecoenzymatic Stoichiometry and Ecological Theory. Annual Review in Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 43:313–43.

Sinsabaugh RL, Lauber CL, Weintraub MN, Ahmed B, Allison SD, Crenshaw C, Contosta AR, Cusack D, Frey S, Gallo ME, Gartner TB, Hobbie SE, Holland K, Keeler BL, Powers JS, Stursova M, Takacs-Vesbach C, Waldrop MP, Wallenstein MD, Zak DR, Zeglin LH. 2008. Stoichiometry of soil enzyme activity at global scale. Ecology Letters 11:1252–64.

Sirotnak JM, Huntly NJ. 2000. Direct and indirect effects of herbivores on nitrogen dynamics: Voles in riparian areas. Ecology 81:78–87.

Sistla SA, Rastetter EB, Schimel JP. 2014. Responses of a tundra system to warming using SCAMPS: A stoichiometrically coupled, acclimating microbeplantsoil model. Ecological Monographs 84:151–70.

Sitters J, te Beest M, Cherif M, Giesler R, Olofsson J. 2017. Interactive Effects Between Reindeer and Habitat Fertility Drive Soil Nutrient Availabilities in Arctic Tundra. Ecosystems 20:1266–77.

Stark S, Julkunen-Tiitto R, Kumpula J. 2007. Ecological role of reindeer summer browsing in the mountain birch (Betula pubescens ssp. czerepanovii) forests: Effects on plant defense, litter decomposition, and soil nutrient cycling. Oecologia 151:486–98.

Stark S, Männistö MK, Eskelinen A. 2015a. When do grazers accelerate or decelerate soil carbon and nitrogen cycling in tundra? A test of theory on grazing effects in fertile and infertile habitats. Oikos 124:593–602.

Stark S, Männistö MK, Ganzert L, Tiirola M, Häggblom MM. 2015b. Grazing intensity in subarctic tundra affects the temperature adaptation of soil microbial communities. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 84:147–57.

Stark S, Strömmer R, Tuomi J. 2002. Reindeer grazing and soil microbial processes in two suboceanic and two subcontinental tundra heaths. Oikos 97:69–78.

Stark S, Väisänen M. 2014. Insensitivity of Soil Microbial Activity to Temporal Variation in Soil N in Subarctic Tundra: Evidence from Responses to Large Migratory Grazers. Ecosystems 17:906–17.

Väisänen M, Ylänne H, Kaarlejärvi E, Sjögersten S, Olofsson J, Crout N, Stark S. 2014. Consequences of warming on tundra carbon balance determined by reindeer grazing history. Nature Climate Change 4:384–8.

van der Wal R. 2006. Do herbivores cause habitat degradation or vegetation state transition? Evidence from the tundra. Oikos 114:177–86.

van der Wal R, Brooker RW. 2004. Mosses mediate grazer impacts on grass abundance in arctic ecosystems. Functional Ecology 18:77–86.

Wallenstein MD, Mcmahon SK, Schimel JP. 2009. Seasonal variation in enzyme activities and temperature sensitivities in Arctic tundra soils. Global Change Biology 15:1631–9.

Wardle DA, Bardgett RD, Klironomos JN, Setälä H, van der Putten WH, Wall DH. 2004. Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science 304:1629–33.

Weintraub MN, Schimel JP. 2003. Interactions between carbon and nitrogen mineralization and soil organic matter chemistry in arctic tundra soils. Ecosystems 6:129–43.

Wickham H. 2009. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. http://ggplot2.org

Ylänne H, Olofsson J, Oksanen L, Stark S. 2018. Consequences of grazer-induced vegetation transitions on ecosystem carbon storage in the tundra. Functional Ecology 32:1091–102.

Ylänne H, Stark S, Tolvanen A. 2015. Vegetation shift from deciduous to evergreen dwarf shrubs in response to selective herbivory offsets carbon losses: Evidence from 19 years of warming and simulated herbivory in the subarctic tundra. Global Change Biology 21:3696–711.

Zeglin LH, Kluber LA, Myrold DD. 2013. The importance of amino sugar turnover to C and N cycling in organic horizons of old-growth Douglas-fir forest soils colonized by ectomycorrhizal mats. Biogeochemistry 112:679–93.

Zimov SA, Zimov NS, Tikhonov AN, Chapin IS. 2012. Mammoth steppe: A high-productivity phenomenon. Quaternary Science Reviews 57:26–45.

Acknowledgements

We thank Aura Pyysalo and Eero Myrsky for their help in the field, Sirkka Aakkonen for the help with the laboratory analyses, and Patrick Saccone for the help with the light-standardisation of GEP measurements. This work has been supported by the Maj and Tor Nesslings Foundation (to S. Stark) and the Kone Foundation (to H. Ylänne and S. Stark).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Author Contributions

SS and HY concieved the study. HY performed field sampling and processed field CO2 flux data. SS analysed enzymatic activities and microbial respiration. HY conducted statistical analyses. Both authors jointly wrote the text.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ylänne, H., Stark, S. Distinguishing Rapid and Slow C Cycling Feedbacks to Grazing in Sub-arctic Tundra. Ecosystems 22, 1145–1159 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-018-0329-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-018-0329-y