Abstract

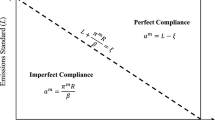

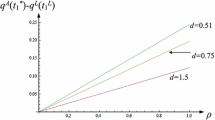

This paper examines the consequences of an increase in the expected fine for non-compliance with an environmental design standard for an industry with Cournot competition and free entry. Our research question is timely and relevant, given recent policy proposals to raise environmental fines. We describe the range, in which changes in the environmental fine have no consequences, and detail the various effects that emerge otherwise. It is established that an increase in the expected fine for non-compliance may have adverse welfare consequences, while it always serves the purpose of inducing a greater share of firms to adopt the prescribed technology. However, when there are limits with respect to the sanctions, it may be welfare-maximizing to have no deterrence at all.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See the press release ‘Putting a price on global environmental damage’ by Principles for Responsible Investment, issued October 6, 2010.

In the context of environmental policy, administrative authorities generally have a significant influence on how such regulations are formulated, interpreted, and enforced (e.g., Faure 2009). For example, the USA’s Environmental Protection Agency has considerable discretion, regarding the penalties assessed under the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 (Besanko 1987).

See Requate (2005a) for a survey of the literature on the adoption incentives induced by different environmental policy instruments.

Baumann and Friehe (2012) provide a related argument for imperfectly enforced employment protection legislation.

For a survey of the literature on optimal law enforcement, refer to Polinsky and Shavell (2007).

It is standard procedure to consider exogenous adoption costs in the technology adoption literature. However, there are other contributions that explicitly address the innovation sector and firms investing in R&D (see the survey by Requate 2005a).

The simplifying assumption of a linear demand function is innocuous for our qualitative results.

As explained below, even the regulator finds out about the type of the firm only after investing monitoring effort and then only with some probability.

Focusing on \( n>3\) allows us to exclude some unimportant case distinctions when we turn to the comparative-statics analysis of the model which rely on a rather large number of firms to allow for an approximation of each single firm’s adoption costs. The restriction on a guarantees positive output levels for a green firm even if all other firms use the brown technology.

In our model, this preferability holds from a social standpoint when the level of environmental harm is suffciently high.

For example, the Dutch Criminal Code sets out a hierarchy of monetary fines depending on the category of the offense. For a survey of criminal sanctions, see, for instance, ‘Criminal Penalties in EU Member States Environmental Law’ available at ec.europa.eu/environment/legal/crime/.

We assume that the expected fine is a parameter that we will vary in our comparative-statics analysis. This is a simplification. For example, Bar-Gill and Harel (2001) discuss the scenario, in which the rate of offending feeds back into the level of the expected sanction.

In Sect. 4, we compare results to a scenario, in which the policy maker can observe an individual firm’s adoption cost and prescribe the technology to be used based on this information.

In our numerical example to be presented after the description of stage 1, market exit is never a profitable option for firms after having sunk the market entry costs.

A more accurate approximation is \( \alpha (m)=(2m-1)/(2n)\), but our simplification is not important for our qualitative results.

Detailed calculations using computational software are available from the authors upon request.

In the determination of \( \widetilde{m}\), it was recognized that an additional green firm implies a decrease in total output X (tantamount to an increase in the market price) and a higher output level of green firms. Both effects dampen the negative impact that results for profits from switching to the green technology. However, these effects are absent in the first line of (27).

In the present example, firms would not want to exit the market even when both their adoption costs and the expected sanction are high.

References

Arguedas C, Camacho E, Zofio JL (2010) Environmental policy instruments: technology adoption incentives with imperfect compliance. Environ Resour Econ 47:261–274

Bar-Gill O, Harel A (2001) Crime rates and expected sanctions: the economics of deterrence revisited. J Legal Studies 30:485–501

Barnett AH (1980) The Pigouvian tax rule under monopoly. Am Econ Rev 70:1037–1041

Baumann F, Friehe T (2012) On the evasion of Employment Protection Legislation. Labour Econ 19:9–17

Besanko D (1987) Performance versus design standards in the regulation of pollution. J Public Econ 34:19–44

Endres A, Bertram R, Rundshagen B (2007) Environmental liability law and induced technical change—the role of discounting. Environ Resour Econ 36:341–366

Endres A (2011) Environmental economics—theory and policy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Endres A, Friehe T (2011) Incentives to diffuse advanced abatement technology under environmental liability law. J Environ Econ Manag 62:30–40

Farzin YH (2003) The effects of emissions standards on industry. J Regul Econ 24:315–327

Farzin YH (2004) Can stricter environmental standards benefit the industry and enhance welfare? Ann Econ Stat 75(76):223–255

Faure M (2009) Environmental crimes. In: Garoupa N (ed) Criminal law and economics. Edward Elgar

Goerke L, Runkel M (2006) Profit tax evasion under oligopoly with endogenous market structure. National Tax J 59:851–857

Goerke L, Runkel M (2011) Tax evasion and competition. Scott J Polit Econ 58:711–736

Goeschl T, Jürgens O (2014) Criminalizing environmental offences: when the prosecutor’s helping hand hurts. Eur J Law Econ 37:199–219

Helfand GE (1991) Standards versus standards: the effects of different pollution restrictions. Am Econ Rev 81:622–634

Hueth B, Melkonyan T (2009) Standards and the regulation of environmental risk. J Regul Econ 36:219–246

Katsoulacos Y, Xepapadeas A (1995) Environmental policy under oligopoly with endogenous market structure. Scand J Econ 97:411–420

Keeler AG (1991) Non-compliant firms in transferable discharge permit markets: some extensions. J Environ Econ Manag 21:180–189

Lee SH (1999) Optimal taxation for polluting oligopolists with endogenous market structure. J Regul Econ 15:293–308

Macho-Stadler I, Perez-Castrillo D (2006) Optimal enforcement policy and firms’ emissions and compliance with environmental taxes. J Environ Econ Manag 51:110–131

Mahenc P (2007) Are green products over-priced? Environ Resour Econ 38:461–473

Malik AS (1990) Markets for pollution control when firms are non-compliant. J Environ Econ Manag 18:97–106

Montero JP (2002) Prices vs. quantities with incomplete enforcement. J Public Econ 85:435–454

Murphy JJ, Stranlund JK (2006) Direct and market effects of enforcing emissions trading programs: an experimental analysis. J Econ Behav Org 61:217–233

Polinsky AM, Shavell S (2007) Public enforcement of law. In: Polinsky AM, Shavell S (eds) Handbook of law and economics, vol 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Requate, T., 2005b. Environmental policy under imperfect competition—a survey. University of Kiel Economics Working Paper 2005-12

Requate T (2005a) Dynamic incentives by environmental policy instruments—a survey. Ecol Econ 54:175–195

Requate T, Unold W (2003) Environmental policy incentives to adopt advanced abatement technology: will the true ranking please stand up? Eur Econ Rev 47:125–146

Rousseau S, Proost S (2005) Comparing environmental policy instruments in the presence of imperfect compliance: a case study. Environ Resour Econ 32:337–365

Rousseau S, Proost S (2009) The relative efficiency of market-based environmental policy instruments with imperfect compliance. Int Tax Public Financ 16:25–42

Sandmo A (2002) Efficient environmental policy with imperfect compliance. Environ Resour Econ 23:85–103

Villegas C, Coria J (2010) On the interaction between imperfect compliance and technology adoption: taxes vs. tradeable emissions permits. J Regul Econ 38:274–291

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Dirk Heine, the participants of the 2014 World Congress of Environmental and Resource Economists in Istanbul, three anonymous referees, and co-editor Y. H. Farzin for very helpful comments.

About this article

Cite this article

Baumann, F., Friehe, T. Design standards and technology adoption: welfare effects of increasing environmental fines when the number of firms is endogenous. Environ Econ Policy Stud 19, 427–450 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10018-016-0166-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10018-016-0166-1