Abstract

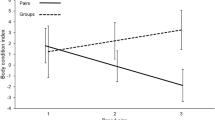

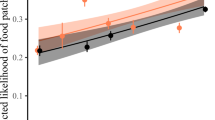

Male harassment toward females during the breeding season may have a negative effect on their reproductive success by disturbing their foraging activity, thereby inducing somatic costs. Accordingly, it is predicted that females will choose mates based on their ability to provide protection or will aggregate into large groups to dilute per capita harassment level. Conversely, increasing group size may also lead to a decrease in foraging activity by increasing foraging competition, but this effect has rarely been considered in mating tactic studies. This study examined the importance of two non-exclusive hypotheses in explaining the variations of the female activity budget during the breeding season: the male harassment hypothesis, and the female foraging competition hypothesis. We used focal observations of female activity from known mating groups collected during the breeding season from a long-term (15 years) study on reindeer Rangifer tarandus. We found that females were more disturbed (i.e., spent less time feeding) in the presence of young dominant males, and marginally disturbed in the presence of satellite males, which supports the male harassment hypothesis. We also found that female disturbance level increased with group size, being independent of the adult sex ratio. Consequently, these results rejected the dilution effect, but strongly supported the foraging competition hypothesis. This study therefore highlights a potential conflict in female behaviour. Indeed, any gains from harassment protection were negated by an increase of 6–7 females, since adult males lead larger groups than young males.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Berger J (1978) Group size, foraging, and antipredator ploys: an analysis of bighorn sheep decisions. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 4:91–99. doi:10.1007/BF00302563

Bierbach D, Sassmannshausen V, Streit B, Arias-Rodriguez L, Plath M (2013) Females prefer males with superior fighting abilities but avoid sexually harassing winners when eavesdropping on male fights. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 67:675–683. doi:10.1007/s00265-013-1487-8

Body G, Weladji RB, Holand Ø, Nieminen M (2014) Highly competitive reindeer males control female behavior during the rut. PLoS ONE 9:e95618

Body G, Weladji RB, Holand Ø, Nieminen M (2015) Fission-fusion group dynamics in reindeer reveal an increase of cohesiveness at the beginning of the peak rut. Acta Ethol 18:101–110. doi:10.1007/s10211-014-0190-8

Bro-Jørgensen J (2011) Intra- and intersexual conflicts and cooperation in the evolution of mating strategies: lessons learnt from ungulates. Evol Biol 38:28–41. doi:10.1007/s11692-010-9105-4

Burnham K, Anderson D (2002) Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretical approach. Springer, New York

Byers JA, Moodie JD, Hall N (1994) Pronghorn females choose vigorous mates. Anim Behav 47:33–43

Cameron EZ, Setsaas TH, Linklater WL (2009) Social bonds between unrelated females increase reproductive success in feral horses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:13850–13853. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900639106

Carranza J (1995) Female attraction by males versus sites in territorial rutting red deer. Anim Behav 50:445–453. doi:10.1006/anbe.1995.0258

Carranza J, Valencia J (1999) Red deer females collect on male clumps at mating areas. Behav Ecol 10:525–532. doi:10.1093/beheco/10.5.525

Clutton-Brock TH, McAuliffe K (2009) Female mate choice in mammals. Q Rev Biol 84:3–27

Clutton-Brock TH, Parker GA (1992) Potential reproductive rates and the operation of sexual selection. Q Rev Biol 67:437–456

Clutton-Brock TH, Vincent ACJ (1991) Sexual selection and the potential reproductive rates of males and females. Nature 351:58–60

Clutton-Brock TH, Price OF, MacColl ADC (1992) Mate retention, harassment, and the evolution of ungulate leks. Behav Ecol 3:234–242. doi:10.1093/beheco/3.3.234

Crawley MJ (2007) The R book. Wiley, Chichester

Danchin E, Giraldeau L-A, Cézilly F (2008) Behavioural ecology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

De Jong K, Forsgren E, Sandvik H, Amundsen T (2012) Measuring mating competition correctly: available evidence supports operational sex ratio theory. Behav Ecol 23:1170–1177. doi:10.1093/beheco/ars094

Emlen ST, Oring LW (1977) Ecology, sexual selection, and the evolution of mating systems. Science 197:215–223

Festa-Bianchet M (1998) Condition-dependent reproductive success in bighorn ewes. Ecol Lett 1:91–94. doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.1998.00023.x

Focardi S, Pecchioli E (2005) Social cohesion and foraging decrease with group size in fallow deer (Dama dama). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 59:84–91. doi:10.1007/s00265-005-0012-0

Fortin D, Fortin M-E, Beyer HL, Duchesne T, Courant S, Dancose K (2009) Group-size-mediated habitat selection and group fusion–fission dynamics of bison under predation risk. Ecology 90:2480–2490

Gittleman JL, Thompson SD (1988) Energy allocation in mammalian reproduction. Am Zool 28:863–875. doi:10.1093/icb/28.3.863

Hewison AJM, Vincent JP, Reby D (1998) Social organization of European roe deer. In: Andersen R, Duncan P, Linnell JDC (eds) The European roe deer: the biology of success. Scandinavian University Press, Oslo, pp 189–219

Holand Ø, Weladji RB, Røed KH, Gjøstein H, Kumpula J, Gaillard J-M, Smith ME, Nieminen M (2006) Male age structure influences females’ mass change during rut in a polygynous ungulate: the reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 59:682–688. doi:10.1007/s00265-005-0097-5

Isvaran K (2005) Variation in male mating behaviour within ungulate populations : patterns and processes. Curr Sci 89:1192–1199

Kojola I (1986) Rutting behaviour in an enclosured group of wild forest reindeer. Rangifer 1:173–179

Kojola I, Nieminen M (1988) Aggression and nearest neighbour distances in female reindeer during the rut. Ethology 77:217–224. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1988.tb00205.x

Komers PE, Birgersson B, Ekvall K (1999) Timing of estrus in fallow deer is adjusted to the age of available mates. Am Nat 153:431–436

L’Italien L, Weladji RB, Holand Ø, Røed KH, Nieminen M, Côté SD (2012) Mating group size and stability in reindeer Rangifer tarandus: the effects of male characteristics, sex ratio and male age structure. Ethology 118:783–792. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2012.02073.x

Lent P (1965) Rutting behaviour in a barren-ground caribou population. Anim Behav 13:259–264. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(65)90044-8

Linklater W, Cameron E, Minot E, Stafford K (1999) Stallion harassment and the mating system of horses. Anim Behav 58:295–306. doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1155

Lipetz VE, Bekoff M (1982) Group size and vigilance in pronghorns. Z Tierpsychol 58:203–216

Makowicz AM, Schlupp I (2013) The direct costs of living in a sexually harassing environment. Anim Behav 85:569–577. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.12.016

Marshall HH, Carter AJ, Rowcliffe JM, Cowlishaw G (2012) Linking social foraging behaviour with individual time budgets and emergent group-level phenomena. Anim Behav 84:1295–1305. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.09.030

Martin P, Bateson P (2007) Measuring behaviour: an introductory guide, 3rd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

McMahon CR, Bradshaw CJA (2004) Harem choice and breeding experience of female southern elephant seals influence offspring survival. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 55:349–362. doi:10.1007/s00265-003-0721-1

Melnycky N, Weladji RB, Holand Ø, Nieminen M (2013) Scaling of antler size in reindeer (Rangifer tarandus): sexual dimorphism and variability in resource allocation. J Mammal 6:1371–1379. doi:10.1644/12-MAMM-A-282.1

Nieminen M (2013) Response distances of wild forest reindeer (Rangifer tarandus fennicus Lönnb.) and semi-domestic reindeer (R.t. tarandus L.) to direct provocation by a hu- man on foot/snowshoes. Rangifer 33:1–15

Pays O, Fortin D, Gassani J, Duchesne J (2012) Group dynamics and landscape features constrain the exploration of herds in fusion–fission societies: the case of European roe deer. PLoS ONE 7:e34678. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034678

R Development Core Team (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.r-project.org/

Réale D, Boussès P, Chapuis J (1996) Female-biased mortality induced by male sexual harassment in a feral sheep population. Can J Zool 74:1812–1818

Reimers E, Røed KH, Colman JE (2012) Persistence of vigilance and flight response behaviour in wild reindeer with varying domestic ancestry. J Evol Biol 25:1543–1554. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02538.x

Rodney D, Boert J (1985) Seasonal activity of the Denali caribou herd, Alaska. Rangifer 5:32–42

Ropstad E (2000) Reproduction in female reindeer. Anim Reprod Sci 60–61:561–570

Stephens DW, Brown JS, Ydenberg RC (2007) Foraging: behavior and ecology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Symonds MRE, Moussalli A (2010) A brief guide to model selection, multimodel inference and model averaging in behavioural ecology using Akaike’s information criterion. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 65:13–21. doi:10.1007/s00265-010-1037-6

Tennenhouse EM, Weladji RB, Holand Ø, Røed KH, Nieminen M (2011) Mating group composition influences somatic costs and activity in rutting dominant male reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 65:287–295. doi:10.1007/s00265-010-1043-8

Tennenhouse EM, Weladji RB, Holand Ø, Nieminen M (2012) Timing of reproductive effort differs between young and old dominant male reindeer. Ann Zool Fenn 49:152–160

Tettamanti F, Viblanc VA (2014) Influences of mating group composition on the behavioral time-budget of male and female Alpine Ibex (Capra ibex) during the rut. PLoS ONE 9:e86004. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086004

Tobler M, Schlupp I, Plath M (2011) Costly interactions between the sexes: combined effects of male sexual harassment and female choice? Behav Ecol 22:723–729. doi:10.1093/beheco/arr044

Weir LK (2013) Male–male competition and alternative male mating tactics influence female behavior and fertility in Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 67:193–203. doi:10.1007/s00265-012-1438-9

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mika Tervonen of the Finnish Reindeer Herder’s Association for the management of Reindeer in Finland, and Heikki Törmänen of the Reindeer Research Station for compiling this long-term database. We thank Hallvard Gjøstein, Eliana Pintus, Sacha Engelhardt and numerous field crew members who helped with data collection over the years, and Juan Carranza, Denis Réale and two anonymous reviewers for comments. Handling of animals and data collection was done in agreement with the Animal Ethics and Care certificate provided by Concordia University (AREC-2010-WELA and AREC-2011-WELA) and by the Finnish National Advisory Board on Research Ethics.

Author contribution statement

GB, RBW, ØH and MN conceived and designed the experiments. SU, GB, RBW, ØH performed the experiments. SU, GB analyzed the data. SU, GB, RBW wrote the manuscript. ØH, MN provided editorial advices.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by Ilpo Kojola.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Uccheddu, S., Body, G., Weladji, R.B. et al. Foraging competition in larger groups overrides harassment avoidance benefits in female reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). Oecologia 179, 711–718 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-015-3392-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-015-3392-5