Abstract

Background

Percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) with drug-coated balloons (DCB) might be a promising trade-off between balloon angioplasty and drug-eluting stents, since DCB inhibit neointimal proliferation and limit duration of dual antiplatelet therapy. We investigated the safety, feasibility, and 6-month results of fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided use of the paclitaxel-coated SeQuent Please® balloon without stenting for elective PCI of de novo lesions.

Methods and results

In 46 patients (54 lesions) with stable symptomatic coronary artery disease (CAD), a FFR-guided POBA (plain old balloon angioplasty) was performed. In case of a sufficient POBA result with residual stenosis < 40 %, FFR > 0.8 and no severe dissection, the target lesion was finally dilated using the DCB. Quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) was performed before and after the index procedure and at 6-month follow-up (f/u) to calculate late lumen loss (LLL) and net luminal gain (NLG). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed at f/u to assess vascular remodeling. DCB-only treatment was applied to 43 patients (51 lesions), while 3 patients (3 lesions) needed provisional stenting. Invasive f/u was completed in 39 patients (47 lesions). At the stenotic site, the lumen diameter showed a trend toward progressive increase at f/u (LLL: −0.13 ± 0.44 mm, n.s.; NLG: 1.10 ± 0.53 mm, p < 0.001) without aneurysm formation or restenosis after DCB-only treatment.

Conclusions

FFR-guided DCB-only PCI of de novo lesions appeared feasible and safe in stable CAD with clopidogrel discontinuation after 4 weeks, showing a trend toward positive vessel remodeling without lumen loss at 6 months.

Clinical trial registration http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT02120859

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plain-old balloon angioplasty (POBA) was introduced in the 1980 s, but is of limited use today due to high restenosis rates (30–50 %) and possible complications of acute and subacute vessel closure [1]. Thus, bare metal stents (BMS) were developed to overcome these limitations at the expense of in-stent restenosis due to intimal hyperplasia. Newer generation drug-eluting stents (DES) proved to effectively suppress neointimal proliferation and delayed restenosis rates are now only 5–15 % [2]. However, a foreign body and local hypersensitivity reactions seem to play a pivotal role for the development of restenosis and late stent thrombosis after stenting [3, 4]. Also, positive vessel remodeling is hindered by a persistent metallic cage and preserving vasomotion after angioplasty is of growing interest.

So far, DCB angioplasty has proven its value in the interventional treatment of de novo stenosis in small coronary vessels, in-stent restenosis or for angioplasty of the side branch in bifurcation stenosis [5–14]. However, there is still limited data and reluctance to treat stenoses in native coronaries of any size with this interventional strategy due to the fear of periprocedural and subacute complications with unfavorable outcome and potential need for bail-out stenting. DCB angioplasty requires only 4 weeks of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), which is a considerable advantage since bleeding complications after PCI have a negative impact on clinical outcomes, and are of health-economical interest.

Aims of the study

We aimed to investigate the feasibility of fractional flow reserve (FFR)-guided use of paclitaxel-coated balloons (PCB) with only provisional bare metal stenting for elective PCI of de novo coronary lesions in an all-comers population. Outcomes were evaluated at 6 months by invasive follow-up (f/u) using angiography and optical coherence tomography (OCT) in addition to clinical data at 1 year f/u.

Methods

Trial design and study setting

The presented study (“Optical coherence tomography to investigate FFR-guided DCB-only elective coronary angioplasty—OCTOPUS-2”; http://www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02120859) is a prospective, single-center, single-arm, investigator-initiated study that was conducted between 10/2012 and 11/2014 at the University Hospital of Jena, Germany. The study was approved by the local ethical committee and conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All study participants gave informed written consent. The predefined sample size was 50 patients.

Interventions

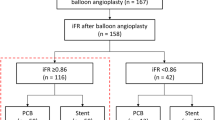

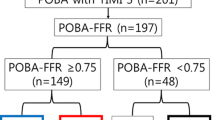

Patients with stable coronary artery disease and indication for elective PCI of a de novo stenosis were suitable for study participation (Online Resource, Fig. 1). Quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) and FFR using an intracoronary bolus of adenosine (60 µg for the right coronary artery and 120 µg for the left coronary artery) after placement of a pressure wire far distal from the stenosis were performed at baseline. FFR was not performed in diameter stenosis <40 %, or >75 % in patients with conclusive symptoms and pathologic non-invasive ischemia testing. If FFR at baseline >0.8, PCI was deferred, otherwise predilation with a non-coated semi-compliant balloon was performed. Provisional stenting was only performed in case of residual diameter stenosis ≥40 % or flow-limiting dissections (Fig. 1). Otherwise, the lesion was dilated with a Sequent Please® paclitaxel-coated balloon (B Braun Melsungen GmbH, Germany). Slow balloon inflation, longer inflation time (60 s), low inflation pressures and higher balloon/artery (b/a) ratio were attempted to avoid large dissections and to achieve sufficient angioplasty results.

Outcome measures

Invasive f/u with QCA and OCT was attempted in all patients after 6 months. Outcome measures were predefined.

-

1.

Primary outcome measures

-

Late lumen loss [LLL in mm; minimal luminal diameter (MLD)postprocedural − MLD6-month f/u] within the treated segment by QCA

-

-

2.

Secondary outcome measures

-

Net luminal gain (NLG in mm; MLD6-month f/u − MLDbaseline)

-

-

3.

OCT-derived outcomes

-

Lumen- and vessel-size measurements, plaque evaluation and dissection healing within the treated segment at 6 months

-

-

4.

Clinical outcomes

-

Target lesion revascularization (TLR)

-

Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as cardiac death, acute myocardial infarction, and revascularization (target and non-target vessel revascularization) at 6-month and 1 year clinical f/u. Clinical f/u was conducted by a structured telephone interview and using the hospital database.

-

Data collection

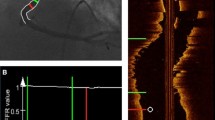

QCA according to the 15-coronary tree segment system was assessed offline by two independent observers (C.D., S.O.) using the same projections for baseline and f/u (CAAS version 5.9.2, 2012, Pie Medical Imaging, Maastricht, Netherlands). Dissections were classified as type A–F according to the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) criteria [15]. Distal coronary flow was assessed according to thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow classification [16]. OCT images were acquired with an automated pullback of 20 mm/s (St. Jude Medical Ilumien™), analyzed offline and blinded to the coronary angiogram. A computational algorithm was applied for dissection and plaque analysis as described before: Plaque morphology was assessed according to the international consensus [17, 18]. Plaques and dissections were manually traced in each cross section, and according volumes were computed through the integral of cross-sectional measurements. Luminal surface areas were calculated by applying the Shoelace formula. Calculated OCT parameters were displayed as spread-out vessel charts (Fig. 2).

Example of a performed DCB-only PCI of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery with final PCI result showing an angiographically determined type B dissection (left) with complete resolution during re-angiography after 6 months (right-top). However, OCT imaging at 6-months f/u still reveals some minor dissections, which are illustrated with coronary plaque measurements in a spread-out vessel chart of the treated vessel segment (right-bottom)

Statistical analysis

Patient data were archived in a customized Microsoft Access (Microsoft Inc., Redmond) database. SPSS (version 21, IBM SPSS statistics) was used for statistical analysis. Continuous and normally distributed variables were analyzed with the Student t test and categorical variables with the Pearson χ 2 test. Two sided p values <0.05 were accepted as statistically significant. Paired t test and Bland and Altman agreement analysis were used for comparison of QCA and OCT measurements.

Results

Study population

We included 46 consecutive patients with 54 study lesions (Fig. 1). Provisional stenting was necessary in three study patients (5.9 %; three lesions). Two patients (two lesions) were lost to 6-month invasive f/u (loss of f/u 4.3 %) due to deterioration of renal function in one patient and refusal of re-angiography in another patient. However, clinical f/u data are available for all patients. Six-month invasive f/u was completed in 39 patients (47 lesions) including 45 lesions with sufficient OCT imaging quality (Fig. 1).

Baseline clinical and procedural characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 show baseline clinical characteristics and procedural data of the study population. Acute lumen gain (MLDpostprocedural − MLDbaseline) was 0.98 ± 0.31 mm. Mean FFR-raised from 0.64 ± 0.19 to 0.91 ± 0.06 (p < 0.05, Table 2). To achieve a sufficient increase of FFR relatively high b/a ratios (oversize ratio 1.27 ± 0.19) were applied (Table 2). Within 24 h after PCI troponin I elevations were detected in three patients with a mean value of 213.3 ± 141.9 ng/ml. However, ECG changes were not observed and clinical course remained uneventful in all patients without further actions needed.

Clinical outcomes and adverse events

Three major adverse cardiovascular events were observed in the study population within 6 months (Intention-to-treat analysis, Table 3). There were two target lesion failures with the need for revascularization: one repeated PCI due to a progressive dissection was necessary within 4 weeks after DCB-only angioplasty and one coronary artery bypass graft was done due to significant in-stent stenosis after DCB use with provisional bare metal stenting. One cardiac death due to ventricular fibrillation occured, however, this was unrelated to the study procedure, since autopsy revealed a patent target vessel.

Invasive evaluation at 6-month follow-up

Angiography

Our results show a trend toward progressive lumen enlargement at the stenotic site and positive net lumen gain at 6-month f/u (Table 3; Online Resource: Figs. 3a–c). More importantly, no focal aneurysm formation or restenosis at 6-month f/u after DCB-only angioplasty were observed. Most of the initially observed type A and B dissections (N = 27 of 51 lesions; 52.9 %; Table 2) were completely healed at f/u (Fig. 2). Angiographically only four small type A dissections were found at 6-month f/u without need for further actions.

Oct

OCT imaging at 6-month f/u was focused on dissection assessment (Table 4). OCT revealed small focal dissections in 42 % of the lesions that were judged angiographically as insignificant. Contrary, in two out of four angiographical type A dissections at f/u, OCT found no evidence of focal dissection (Table 4; Fig. 2). We found no predictors (e.g., vessel angulation, vessel diameter, lesion length, calcification, number of dilation, oversize ratio, diabetes, renal insufficiency, LDL-levels, etc.) for the occurrence of dissections either after PCI or at 6-month f/u.

OCT plaque analysis revealed 4.1 ± 3.0 plaques with a total plaque volume of 21.8 ± 24.6 mm3 and a total luminal plaque surface area of 10.8 ± 9.4 mm2 per investigated target vessel segment. In detail, there were 0.2 ± 0.5 fibrotic plaques, 1.3 ± 1.6 calcified plaques, 1.5 ± 1.3 mixed plaques, and 1.1 ± 1.2 fibroatheromas per vessel segment (Fig. 2). Thin-cap (< 65 µm) fibroatheromas (TCFA) were not observed. No association between plaque burden and the incidence of dissections was found.

There was a good correlation (r = 0.738; 95 % CI −0.37 to −0.11 mm; p < 0.001) between MLD measurements at f/u with QCA (MLDQCA 1.97 ± 0.62 mm) and OCT (MLDOCT 1.73 ± 0.44 mm). Agreement between QCA and OCT according to Bland–Altman data plotting was higher in smaller diameter vessels.

Discussion

The main findings of this prospective study are: (1) DCB-only angioplasty in all-comers is effective and safe with no subacute vessel closure and low MACE rate (4.7 % at 6-months) with only 4 weeks of DAPT, (2) a trend toward positive vessel remodeling with late lumen enlargement is seen at 6-month invasive f/u, (3) conversion rate to bail-out stenting under FFR guidance is very low (6 %), (4) clinically silent type A and B dissections are mostly healed at f/u, (5) angiography is unreliable for a correct diagnosis of small residual dissections.

Evidence for DCB-only angioplasty as a primary interventional strategy is growing. So far, published data are stemming from mainly retrospective registries and case reports [14, 19–22]. One serial, prospective study using IVUS and FFR analyzed only 27 from 48 initially treated patients [23]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective, officially registered study with a dedicated, predefined procedural protocol that investigates the feasibility of elective DCB-only PCI in all-comers and provides a nearly completed 6-month invasive and clinical f/u in all patients. Earlier studies of DCB-only angioplasty of de novo stenoses showed a high conversion rate to stenting (11.9–32.8 %), or investigated a preselected study population [20, 21, 23]. Contrary, bail-out stenting in our study was necessary only in 6 % of cases.

DCB angioplasty leads to lumen enlargement at 6-month invasive f/u in many patients expressed as overall LLL of −0.13 ± 0.44 mm (Online Resource: Figs. 3a–c). Our results on positive vessel remodeling are in agreement with previous studies also showing luminal gain at variable f/u times (Scheller 2013: LLL −0.25 to −0.18 mm; Kleber 2015: late lumen increase in 69 % of the lesion, Her 2016: LLL: −0.12 ± 0.30 mm; Shin 2015: LLL 0.05 ± 0.27 mm; Ann 2016: LLL 0.02 ± 0.27 mm) [14, 19, 21–23]. Only the Valentine´s II trial showed a LLL of 0.38 ± 0.39 mm at 6–9 months f/u. However, this might underline the necessity of adequate lesion preparation since predilation in the Valentine´s II trial was conducted in only 85 %, and DCB diameters were significantly smaller despite comparable RLDs. Contrary to the consensus on DCB treatment, the mean b/a ratio of 1.27 in this study was considerably higher than recommended (0.8–1.0), but is in line with values reported by other studies (1.15–1.18). Thus, oversizing seems of crucial importance to achieve sufficient acute and long-term results [14, 21, 22].

Post-interventional FFR is less well evaluated, but pressure gradient measurements proved to be a useful and reliable tool to guide immediate results of angioplasty [24, 25]. In our study, we used a cut-off of >0.8 for post-interventional FFR, which one might find unusually low to accept final angioplasty results. FFR values <0.95 post-stenting are associated with adverse long-term results [24]. However, to the best of our knowledge, cut-off values for FFR after a DCB-only procedure have never been investigated yet. Also, given the higher acute lumen gain after stent implantation, and the expected late lumen enlargement after DCB-only angioplasty, one must not extrapolate data from publications investigating stent results. In this light, clinical and angiographic data in our study seem reassuring for FFR values > 0.8 after DCB-only, but this hypothesis needs confirmation in further studies with longer follow-up times.

Polymers in DES platforms are associated with disadvantageous vessel wall effects, while DCB are polymer-free. DCB angioplasty allows uniform distribution of the antiproliferative drug to the vessel wall, and significantly higher paclitaxel-concentrations are used compared to paclitaxel-eluting stents [26, 27]. However, properties of DCB´s should not be understood as “class effects” [28]. Current evidence for vessel wall expansion is the strongest for paclitaxel and is histologically proven as media wall thinning and cell necrosis in addition to inhibition of smooth muscle cells [18, 29–31]. Out of the available paclitaxel-coated balloons, the Sequent Please™ DCB used in this study has been best investigated. This is of importance since vessel wall effects of paclitaxel are known to be dose-dependent [32, 33].

We found no aneurysm formation at the stenotic site at f/u, which confirms another study that specifically investigated the incidence of focal coronary artery aneurysm after DCB angioplasty [34].

Plaque regression might also account for the specific effects of positive vessel remodeling. A small, serial IVUS study found no change of mean plaque area 9 months after DCB angioplasty but a significant decrease of atheroma volume [23]. The mentioned study also found plaque modulation since out of nine initially observed TCFA’s only five TCFA’s were seen at f/u, which the authors interpreted as a result of cap thickening and transformation to pathological intimal thickening [23]. In line with this observation, we did not find any TCFA’s at 6-month f/u within the treated segment using OCT, which is more reliable in determining TCFAs than IVUS [35].

Another focus of our study was the evaluation of dissections as a result of angioplasty and its impact on midterm outcomes. By applying the mentioned procedural precautions and intracoronary pressure monitoring, bail-out stenting was grossly preventable. From the only small residual dissections seen at baseline, most dissections were completely healed at f/u, which is in line with a previously published study [36]. Interestingly, angiography is largely misleading in evaluation of small dissections of NHLBI type A, and no real association between dimensions of dissection investigated by OCT and angiography was found.

Novel interventional approaches for the therapy of stable stenosis try to eliminate the necessity for a permanent foreign body since it has been shown that in-stent restenosis is at least partly caused by local hypersensitivity reactions and neoatherosclerosis in response to the metal material, the polymer or the antiproliferative drug [37]. Lately, bioresorbable vascular scaffolds (BVS) are in the focus of interest. Interestingly, for both “metallic free” concepts of BVS and DCB-only angioplasty, late lumen enlargement has been shown, which is contrary to the well-known vessel response after POBA, BMS or DES implantation resulting always in late lumen loss [38, 39]. Also, restoration of vasomotion after angioplasty is advantageous and might maintain positive long-term outcomes including relief of angina symptoms [39, 40]. However, prolonged DAPT for 12 months is needed after BVS implantation. Also, rates of acute and late scaffold thrombosis are not negligible, and seem to be higher compared to newer generation DES [41]. Degradation of the ABSORB™ BVS, which is currently the best investigated scaffold, is with >2 years rather slow and the optimal degradation rate of vascular scaffolds remains to be determined [39]. Contrarily, duration of DAPT after DCB-only angioplasty is with 4 weeks only minimal and reports on acute vessel closure after PCI are very rare. Thus, DCB angioplasty as a stand-alone procedure might be a promising trade-off between POBA, DES, and BVS. On the other hand, it has been shown that BVS has the capacity to “seal” underlying coronary plaques [39, 42]. Whether or not this translates into a favorable long-term course remains nevertheless unclear. Changes in coronary plaques after a DCB-only procedure need to be further investigated, before definitive conclusions and clinical recommendations comparing both concepts can be formulated.

Clinical implications

FFR-guided DCB-only PCI using the Sequent Please balloon is feasible, safe, and effective irrespective of vessel size. Small, non-flow-limiting dissections type A and B with normal FFR values >0.80 do not require stenting and show favorable clinical outcomes. Operator’s training including lesion preparation, choice of balloon size, inflation time and pressure, and evaluation of dissections is necessary to successfully apply a DCB-only strategy as stand-alone procedure and to achieve good clinical outcomes.

Limitations

This study has a relatively small sample size and was intended as a feasibility study to prove the concept of an elective FFR-guided DCB-only angioplasty. Thus, our study is not a randomized trial comparing DCB-only PCI to another study intervention. Since we did not perform OCT at baseline, plaque regression and dissection healing could not be recorded and further serial OCT studies specifically focusing on this aspect are needed.

Conclusion

The concept of FFR-guided DCB-only angioplasty without stenting of de novo lesions in stable CAD is effective and safe with post-procedural DAPT duration of only 4 weeks. Local delivery of paclitaxel induces persistent vessel remodeling leading to lumen enlargement in many cases at 6-month f/u. Intracoronary imaging and FFR are useful to guide angioplasty and to avoid unnecessary stenting. Larger studies are needed to redefine the management of non-flow-limiting dissections and to evaluate long-term outcomes after DCB-only angioplasty in comparison to implantation of drug-eluting stents and scaffolds.

References

Kent KM, Bentivoglio LG, Block PC, Bourassa MG, Cowley MJ, Dorros G, Detre KM, Gosselin AJ, Gruentzig AR, Kelsey SF et al (1984) Long-term efficacy of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA): report from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute PTCA Registry. Am J Cardiol 53:27C–31C

Jensen LO, Thayssen P, Hansen HS, Christiansen EH, Tilsted HH, Krusell LR, Villadsen AB, Junker A, Hansen KN, Kaltoft A, Maeng M, Pedersen KE, Kristensen SD, Botker HE, Ravkilde J, Sanchez R, Aaroe J, Madsen M, Sorensen HT, Thuesen L, Lassen JF (2012) Randomized comparison of everolimus-eluting and sirolimus-eluting stents in patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention: the Scandinavian Organization for Randomized Trials with Clinical Outcome IV (SORT OUT IV). Circulation 125:1246–1255. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.063644

Nakazawa G, Finn AV, Vorpahl M, Ladich ER, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R (2011) Coronary responses and differential mechanisms of late stent thrombosis attributed to first-generation sirolimus- and paclitaxel-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol 57:390–398. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.066

Nakano M, Virmani R (2014) Histopathology of vascular response to drug-eluting stents: an insight from human autopsy into daily practice. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. doi:10.1007/s12928-014-0281-5

Cortese B, Micheli A, Picchi A, Coppolaro A, Bandinelli L, Severi S, Limbruno U (2010) Paclitaxel-coated balloon versus drug-eluting stent during PCI of small coronary vessels, a prospective randomised clinical trial. The PICCOLETO study. Heart 96:1291–1296. doi:10.1136/hrt.2010.195057

Authors/Task Force m, Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A (2014) 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J 35:2541–2619. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278

Kleber FX, Rittger H, Bonaventura K, Zeymer U, Wohrle J, Jeger R, Levenson B, Mobius-Winkler S, Bruch L, Fischer D, Hengstenberg C, Porner T, Mathey D, Scheller B (2013) Drug-coated balloons for treatment of coronary artery disease: updated recommendations from a consensus group. Clin Res Cardiol 102:785–797. doi:10.1007/s00392-013-0609-7

Latib A, Colombo A, Castriota F, Micari A, Cremonesi A, De Felice F, Marchese A, Tespili M, Presbitero P, Sgueglia GA, Buffoli F, Tamburino C, Varbella F, Menozzi A (2012) A randomized multicenter study comparing a paclitaxel drug-eluting balloon with a paclitaxel-eluting stent in small coronary vessels: the BELLO (Balloon Elution and Late Loss Optimization) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 60:2473–2480. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.020

Unverdorben M, Vallbracht C, Cremers B, Heuer H, Hengstenberg C, Maikowski C, Werner GS, Antoni D, Kleber FX, Bocksch W, Leschke M, Ackermann H, Boxberger M, Speck U, Degenhardt R, Scheller B (2009) Paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter versus paclitaxel-coated stent for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis. Circulation 119:2986–2994. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.839282

Unverdorben M, Kleber FX, Heuer H, Figulla HR, Vallbracht C, Leschke M, Cremers B, Hardt S, Buerke M, Ackermann H, Boxberger M, Degenhardt R, Scheller B (2010) Treatment of small coronary arteries with a paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter. Clin Res Cardiol 99:165–174. doi:10.1007/s00392-009-0101-6

Wohrle J, Zadura M, Mobius-Winkler S, Leschke M, Opitz C, Ahmed W, Barragan P, Simon JP, Cassel G, Scheller B (2012) SeQuentPlease World Wide Registry: clinical results of SeQuent please paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty in a large-scale, prospective registry study. J Am Coll Cardiol 60:1733–1738. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.040

Clever YP, Cremers B, von Scheidt W, Bohm M, Speck U, Scheller B (2013) Compassionate use of a paclitaxel coated balloon in patients with refractory recurrent coronary in-stent restenosis. Clin Res Cardiol. doi:10.1007/s00392-013-0617-7

Schulz A, Hauschild T, Kleber FX (2014) Treatment of coronary de novo bifurcation lesions with DCB only strategy. Clin Res Cardiol 103:451–456. doi:10.1007/s00392-014-0671-9

Scheller B, Fischer D, Clever YP, Kleber FX, Speck U, Bohm M, Cremers B (2013) Treatment of a coronary bifurcation lesion with drug-coated balloons: lumen enlargement and plaque modification after 6 months. Clin Res Cardiol 102:469–472. doi:10.1007/s00392-013-0556-3

Holmes DR Jr, Holubkov R, Vlietstra RE, Kelsey SF, Reeder GS, Dorros G, Williams DO, Cowley MJ, Faxon DP, Kent KM et al (1988) Comparison of complications during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty from 1977 to 1981 and from 1985 to 1986: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 12:1149–1155

Chesebro JH, Knatterud G, Roberts R, Borer J, Cohen LS, Dalen J, Dodge HT, Francis CK, Hillis D, Ludbrook P et al (1987) Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial, phase I: a comparison between intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and intravenous streptokinase. Clinical findings through hospital discharge. Circulation 76:142–154

Prati F, Regar E, Mintz GS, Arbustini E, Di Mario C, Jang IK, Akasaka T, Costa M, Guagliumi G, Grube E, Ozaki Y, Pinto F, Serruys PW (2010) Expert review document on methodology, terminology, and clinical applications of optical coherence tomography: physical principles, methodology of image acquisition, and clinical application for assessment of coronary arteries and atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J 31:401–415. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp433

Otto S, Gassdorf J, Nitsche K, Gutierrez-Chico JL, Kryvanos A, Goebel B, Figulla HR, Poerner TC (2016) Time course of vascular response after an a priori strategy of bare metal stent implantation post-dilated with a paclitaxel-coated balloon: implementation of a three dimensional analysis algorithm with optical coherence tomography. Cardiol J 23(3):296–306. doi:10.5603/CJ.a2016.0018

Kleber FX, Schulz A, Waliszewski M, Hauschild T, Bohm M, Dietz U, Cremers B, Scheller B, Clever YP (2015) Local paclitaxel induces late lumen enlargement in coronary arteries after balloon angioplasty. Clin Res Cardiol 104:217–225. doi:10.1007/s00392-014-0775-2

Waksman R, Serra A, Loh JP, Malik FT, Torguson R, Stahnke S, von Strandmann RP, Rodriguez AE (2013) Drug-coated balloons for de novo coronary lesions: results from the Valentines II trial. EuroIntervention 9:613–619. doi:10.4244/EIJV9I5A98

Shin ES, Ann SH, Balbir Singh G, Lim KH, Kleber FX, Koo BK (2015) Fractional flow reserve-guided paclitaxel-coated balloon treatment for de novo coronary lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. doi:10.1002/ccd.26257

Her AY, Ann SH, Singh GB, Kim YH, Yoo SY, Garg S, Koo BK, Shin ES (2016) Comparison of paclitaxel-coated balloon treatment and plain old balloon angioplasty for de novo coronary lesions. Yonsei Med J 57:337–341. doi:10.3349/ymj.2016.57.2.337

Ann SH, Balbir Singh G, Lim KH, Koo BK, Shin ES (2016) Anatomical and physiological changes after paclitaxel-coated balloon for atherosclerotic de novo coronary lesions: serial IVUS-VH and FFR study. PLoS ONE 11:e0147057. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147057

Pijls NH, Klauss V, Siebert U, Powers E, Takazawa K, Fearon WF, Escaned J, Tsurumi Y, Akasaka T, Samady H, De Bruyne B, Fractional Flow Reserve Post-Stent Registry I (2002) Coronary pressure measurement after stenting predicts adverse events at follow-up: a multicenter registry. Circulation 105:2950–2954

van’t Veer M, Pijls NH, Aarnoudse W, Koolen JJ, van de Vosse FN (2006) Evaluation of the haemodynamic characteristics of drug-eluting stents at implantation and at follow-up. Eur Heart J 27:1811–1817. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl134

Speck U, Cremers B, Kelsch B, Biedermann M, Clever YP, Schaffner S, Mahnkopf D, Hanisch U, Bohm M, Scheller B (2012) Do pharmacokinetics explain persistent restenosis inhibition by a single dose of paclitaxel? Circ Cardiovasc Interv 5:392–400. doi:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.967794

Vogt F, Stein A, Rettemeier G, Krott N, Hoffmann R, vom Dahl J, Bosserhoff AK, Michaeli W, Hanrath P, Weber C, Blindt R (2004) Long-term assessment of a novel biodegradable paclitaxel-eluting coronary polylactide stent. Eur Heart J 25:1330–1340. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2004.06.010

Nijhoff F, Stella PR, Troost MS, Belkacemi A, Nathoe HM, Voskuil M, Samim M, Doevendans PA, Agostoni P (2016) Comparative assessment of the antirestenotic efficacy of two paclitaxel drug-eluting balloons with different coatings in the treatment of in-stent restenosis. Clin Res Cardiol 105:401–411. doi:10.1007/s00392-015-0934-0

Pires NM, Eefting D, de Vries MR, Quax PH, Jukema JW (2007) Sirolimus and paclitaxel provoke different vascular pathological responses after local delivery in a murine model for restenosis on underlying atherosclerotic arteries. Heart 93:922–927. doi:10.1136/hrt.2006.102244

Heldman AW, Cheng L, Jenkins GM, Heller PF, Kim DW, Ware M Jr, Nater C, Hruban RH, Rezai B, Abella BS, Bunge KE, Kinsella JL, Sollott SJ, Lakatta EG, Brinker JA, Hunter WL, Froehlich JP (2001) Paclitaxel stent coating inhibits neointimal hyperplasia at 4 weeks in a porcine model of coronary restenosis. Circulation 103:2289–2295

Hou D, Rogers PI, Toleikis PM, Hunter W, March KL (2000) Intrapericardial paclitaxel delivery inhibits neointimal proliferation and promotes arterial enlargement after porcine coronary overstretch. Circulation 102:1575–1581

Aoki J, Colombo A, Dudek D, Banning AP, Drzewiecki J, Zmudka K, Schiele F, Russell ME, Koglin J, Serruys PW, Group TIS (2005) Peristent remodeling and neointimal suppression 2 years after polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent implantation: insights from serial intravascular ultrasound analysis in the TAXUS II study. Circulation 112:3876–3883. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.558601

Weissman NJ, Ellis SG, Grube E, Dawkins KD, Greenberg JD, Mann T, Cannon LA, Cambier PA, Fernandez S, Mintz GS, Mandinov L, Koglin J, Stone GW (2007) Effect of the polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting TAXUS Express stent on vascular tissue responses: a volumetric intravascular ultrasound integrated analysis from the TAXUS IV, V, and VI trials. Eur Heart J 28:1574–1582. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm174

Kleber FX, Schulz A, Bonaventura K, Fengler A (2013) No indication for an unexpected high rate of coronary artery aneurysms after angioplasty with drug-coated balloons. EuroIntervention 9:608–612. doi:10.4244/EIJV9I5A97

Xie Z, Tian J, Ma L, Du H, Dong N, Hou J, He J, Dai J, Liu X, Pan H, Liu Y, Yu B (2015) Comparison of optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound for evaluation of coronary lipid-rich atherosclerotic plaque progression and regression. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 16:1374–1380. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jev104

Kleber FX, Rittger H, Ludwig J, Schulz A, Mathey DG, Boxberger M, Degenhardt R, Scheller B, Strasser RH (2016) Drug eluting balloons as stand alone procedure for coronary bifurcational lesions: results of the randomized multicenter PEPCAD-BIF trial. Clin Res Cardiol. doi:10.1007/s00392-015-0957-6

Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, Mont EK, Kolodgie FD, Ladich E, Kutys R, Skorija K, Gold HK, Virmani R (2006) Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 48:193–202. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.042

Lane JP, Perkins LE, Sheehy AJ, Pacheco EJ, Frie MP, Lambert BJ, Rapoza RJ, Virmani R (2014) Lumen gain and restoration of pulsatility after implantation of a bioresorbable vascular scaffold in porcine coronary arteries. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 7:688–695. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2013.11.024

Serruys PW, Ormiston JA, Onuma Y, Regar E, Gonzalo N, Garcia-Garcia HM, Nieman K, Bruining N, Dorange C, Miquel-Hebert K, Veldhof S, Webster M, Thuesen L, Dudek D (2009) A bioabsorbable everolimus-eluting coronary stent system (ABSORB): 2-year outcomes and results from multiple imaging methods. Lancet 373:897–910. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60325-1

Ong P, Athanasiadis A, Perne A, Mahrholdt H, Schaufele T, Hill S, Sechtem U (2014) Coronary vasomotor abnormalities in patients with stable angina after successful stent implantation but without in-stent restenosis. Clin Res Cardiol 103:11–19. doi:10.1007/s00392-013-0615-9

Lipinski MJ, Escarcega RO, Baker NC, Benn HA, Gaglia MA Jr, Torguson R, Waksman R (2016) Scaffold thrombosis after percutaneous coronary intervention with ABSORB bioresorbable vascular scaffold: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 9:12–24. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2015.09.024

Bourantas CV, Serruys PW, Nakatani S, Zhang YJ, Farooq V, Diletti R, Ligthart J, Sheehy A, van Geuns RJ, McClean D, Chevalier B, Windecker S, Koolen J, Ormiston J, Whitbourn R, Rapoza R, Veldhof S, Onuma Y, Garcia-Garcia HM (2015) Bioresorbable vascular scaffold treatment induces the formation of neointimal cap that seals the underlying plaque without compromising the luminal dimensions: a concept based on serial optical coherence tomography data. EuroIntervention 11:746–756. doi:10.4244/EIJY14M10_06

Acknowledgments

The study has been sponsored by the University of Jena with financial support from B Braun Melsungen GmbH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Poerner, T.C., Duderstadt, C., Goebel, B. et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided coronary angioplasty using paclitaxel-coated balloons without stent implantation: feasibility, safety and 6-month results by angiography and optical coherence tomography. Clin Res Cardiol 106, 18–27 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-016-1019-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-016-1019-4