Abstract

Background

Gastrointestinal (GI) immune-related adverse events (irAEs) commonly limit immune checkpoint inhibitors’ (ICIs) treatment, which is very effective for metastatic melanoma. The independent impact of GI-irAEs on patients’ survival is not well studied. We aimed to assess the impact of GI-irAEs on survival rates of patients with metastatic melanoma using multivariate model.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of patients with metastatic melanoma who developed GI-irAEs from 1/2010 through 4/2018. A number of randomized patients who did not have GI-irAEs were included as controls. Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank test were used to estimate unadjusted survival durations. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate survival predictors; irAEs were included as time-dependent variables.

Results

A total of 346 patients were included, 173 patients had GI-irAEs; 124 (72%) received immunosuppression. In multivariate Cox regression, ECOG 2–3 (HR 2.57, 95%CI 1.44–4.57; P < 0.01), LDH ≥ 618 IU/L (HR 2.20, 95% CI 1.47–3.29; P < 0.01), stage M1c (HR 2.21, 95% CI 1.35–3.60; P < 0.01) were associated with worse OS rates. Any grade GI-irAEs (HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.36–0.78; P < 0.01) was associated with improved OS rates. Immunosuppressive treatment did not affect OS (P = 0.15). High-grade diarrhea was associated with improved OS (P = 0.04). Patients who developed GI-irAEs had longer PFS durations on Cox model (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.41–0.76; P < 0.01).

Conclusion

GI-irAEs are associated with improved OS and PFS in patients with metastatic melanoma. Furthermore, higher grades of diarrhea are associated with even better patients’ OS rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTLA-4:

-

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- FDG PET:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- HQROL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ICI:

-

Immune checkpoint inhibitor

- iCPD:

-

Confirmed progressive disease

- iCR:

-

Immune complete response

- IDC:

-

Immune-mediated diarrhea and colitis

- imRECIST:

-

Immune-modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- iPR:

-

Immune partial response

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- irAE:

-

Immune-related adverse event

- iRECIST:

-

Immune-related response evaluation criteria in solid tumors

- iSD:

-

Immune stable disease

- iUPD:

-

Immune unconfirmed progressive disease

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death protein-1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed death-ligand 1

- PFS:

-

Progression free survival

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Abu-Sbeih H et al (2018) Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis as a predictor of survival in metastatic melanoma. J Immunother Cancer 6(Suppl 1):P537

Ribas A et al (2016) Association of pembrolizumab with tumor response and survival among patients with advanced melanoma. JAMA 315(15):1600–1609

Wolchok JD et al (2017) Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 377(14):1345–1356

Friedman CF, Proverbs-Singh TA, Postow MA (2016) Treatment of the immune-related adverse effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review. JAMA Oncol 2(10):1346–1353

Topalian SL et al (2012) Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 366(26):2443–2454

Herbst RS et al (2014) Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 515(7528):563–567

Puzanov I et al (2017) Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J Immunother Cancer 5(1):95

Haanen J et al (2017) Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 28(suppl_4):iv119–iv142

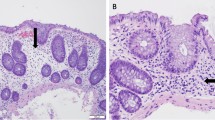

Abu-Sbeih H et al (2018) Importance of endoscopic and histological evaluation in the management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. J Immunother Cancer 6(1):95

Wang Y et al (2018) Endoscopic and Histologic Features of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 24(8):1695–1705

Wang DY et al (2017) Incidence of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related colitis in solid tumor patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncoimmunology 6(10):e1344805

Freeman-Keller M et al (2016) Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res 22(4):886–894

Weber JS et al (2017) Safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy: a pooled analysis of patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol 35(7):785–792

Downey SG et al (2007) Prognostic factors related to clinical response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated by CTL-associated antigen-4 blockade. Clin Cancer Res 13(22 Pt 1):6681–6688

Beck KE et al (2006) Enterocolitis in patients with cancer after antibody blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Clin Oncol 24(15):2283–2289

Wang Y et al (2018) Immune-checkpoint inhibitor-induced diarrhea and colitis in patients with advanced malignancies: retrospective review at MD Anderson. J Immunother Cancer 6(1):37

Oken MM et al (1982) Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 5(6):649–655

Wolchok JD et al (2009) Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res 15(23):7412–7420

Nishino M et al (2013) Developing a common language for tumor response to immunotherapy: immune-related response criteria using unidimensional measurements. Clin Cancer Res 19(14):3936–3943

Nishino M et al (2014) Optimizing immune-related tumor response assessment: does reducing the number of lesions impact response assessment in melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab? J Immunother Cancer 2:17

Seymour L et al (2017) iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol 18(3):e143–e152

Hodi FS et al (2018) Immune-modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (imRECIST). Refining guidelines to assess the clinical benefit of cancer immunotherapy. J Clin Oncol 36(9):850–858

Kaplan EL, Meier P (1958) Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 53(282):457–481

Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc 34(2):187–220

Therneau TM, Grambsch PM (2000) Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. Statistics for Biology and Health

Balch CM et al (2001) Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol 19(16):3622–3634

Tas F (2012) Metastatic behavior in melanoma: timing, pattern, survival, and influencing factors. J Oncol 2012:647–684

Balch CM et al (2009) Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 27(36):6199–6206

Weber JS, Kahler KC, Hauschild A (2012) Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol 30(21):2691–2697

Hua C et al (2016) Association of vitiligo with tumor response in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. JAMA Dermatol 152(1):45–51

Gogas H et al (2006) Prognostic significance of autoimmunity during treatment of melanoma with interferon. N Engl J Med 354(7):709–718

Horvat TZ et al (2015) Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol 33(28):3193–3198

Schadendorf D et al (2017) Efficacy and safety outcomes in patients with advanced melanoma who discontinued treatment with nivolumab and ipilimumab because of adverse events: a pooled analysis of randomized phase II and III trials. J Clin Oncol 35(34):3807–3814

Nordlund JJ et al (1983) Vitiligo in patients with metastatic melanoma: a good prognostic sign. J Am Acad Dermatol 9(5):689–696

Neemann K, Freifeld A (2017) Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in the oncology patient. J Oncol Pract 13(1):25–30

Nesher L, Rolston KV (2013) Neutropenic enterocolitis, a growing concern in the era of widespread use of aggressive chemotherapy. Clin Infect Dis 56(5):711–717

Castilla-Llorente C et al (2014) Prognostic factors and outcomes of severe gastrointestinal GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transpl 49(7):966–971

Roychowdhury DF, Hayden A, Liepa AM (2003) Health-related quality-of-life parameters as independent prognostic factors in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol 21(4):673–678

Acknowledgements

Medical editing of this paper was provided by the Department of Scientific Publications at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Funding

This study was not supported by any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HA-S: conceptualization, data curation, writing-original draft, methodology. FSA: writing-original draft, data curation. WQ: formal analysis, software, review and editing, methodology. YL: conceptualization, writing-review and editing, data curation. SP: conceptualization, writing-review and editing. AD: conceptualization, writing-review and editing, project administration, methodology. YW: conceptualization, writing-review and editing, project administration, methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

This retrospective, single-center study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Approval number: PA18-0472.

Informed consent

This study was granted waiver of consent.

Additional information

Note on previous publication

This paper was partially published as a poster abstract at the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) 2018 conference (Washington, D.C., USA, 7–11 November 2018). Abstract number: P537 [1].

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abu-Sbeih, H., Ali, F.S., Qiao, W. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis as a predictor of survival in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 68, 553–561 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-019-02303-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-019-02303-1