Abstract

Natural rubber (NR), poly(cis-1,4-isoprene), is used in an industrial scale for more than 100 years. Most of the NR-derived materials are released to the environment as waste or by abrasion of small particles from our tires. Furthermore, compounds with isoprene units in their molecular structures are part of many biomolecules such as terpenoids and carotenoids. Therefore, it is not surprising that NR-degrading bacteria are widespread in nature. NR has one carbon-carbon double bond per isoprene unit and this functional group is the primary target of NR-cleaving enzymes, so-called rubber oxygenases. Rubber oxygenases are secreted by rubber-degrading bacteria to initiate the break-down of the polymer and to use the generated cleavage products as a carbon source. Three main types of rubber oxygenases have been described so far. One is rubber oxygenase RoxA that was first isolated from Xanthomonas sp. 35Y but was later also identified in other Gram-negative rubber-degrading species. The second type of rubber oxygenase is the latex clearing protein (Lcp) that has been regularly found in Gram-positive rubber degraders. Recently, a third type of rubber oxygenase (RoxB) with distant relationship to RoxAs was identified in Gram-negative bacteria. All rubber oxygenases described so far are haem-containing enzymes and oxidatively cleave polyisoprene to low molecular weight oligoisoprenoids with terminal CHO and CO–CH3 functions between a variable number of intact isoprene units, depending on the type of rubber oxygenase. This contribution summarises the properties of RoxAs, RoxBs and Lcps.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Natural rubber (NR) is produced mainly by plants and is the characteristic and main component of rubber latex particles. NR-producing species are frequently found in species of the Euphorbiaceae, e.g. in the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) or in the members of the Compositae such as in Taraxacum koksaghyz (Russian dandelion) (van Beilen and Poirier 2007a, b). The ability to synthesise rubber can also be found occasionally in species of other plant families and even in some fungi. Most rubber-accumulating plants synthesise the polymer with the isoprene units in the cis-configuration, whereas some species such as Manilkara chicle or Palaquium gutta synthesise the trans-polymer, leading to rubbers known as chicle or gutta-percha. Poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) latex in Hevea brasiliensis and many other species is synthesised and accumulated in form of globules that can have a diameter of several hundreds of nanometres up to a few micrometres. The rubber particles are stored under pressure in special tissues (laticifers) and are released as latex after injury of the tissue, e.g. by the tapping process or during invading of insect larvae. Latex globules consist of a polyisoprene core that is covered by a phospholipid monolayer (Wadeesirisak et al. 2017; Cornish et al. 1999) into which several proteins such as hevein (Berthelot et al. 2016) and the polymer-synthesising enzyme (cis-polyprenyl-synthetase) are attached (Schmidt et al. 2010; Berthelot et al. 2014). For overviews on rubber biosynthesis and latex globule structure, see Cornish et al. (1999), Cornish (2001), Berthelot et al. (2014) and Epping et al. (2015). Defence against parasites could be one of the main functions for the production of polyisoprene latex given that latex released after damaging the laticifers rapidly coagulates and encapsulates the invading pest.

Rubber-degrading bacteria

Since the invention of crosslinking the polyisoprene chains with sulphur (vulcanisation) by Goodyear in 1844, rubber has been permanently in use in a large industrial scale (currently ≈ 107 tons NR per year). Despite the enormous amounts of rubber particles that are constantly released to the environment by abrasion from tires for a period of meanwhile more than a century, there is no evidence for a long-term accumulation of such rubber particles pointing to the ubiquitous presence and efficiency of rubber-degrading microorganisms. Indeed, rubber-degrading microorganisms have been identified in and isolated from most ecosystems with moderate physical parameters (temperature, pH, salinity). For lists and overviews on rubber-degrading bacteria, see Jendrossek et al. (1997), Rose and Steinbüchel (2005), Warneke et al. (2007), Yikmis and Steinbüchel (2012a), Chengalroyen and Dabbs (2013) and Shah et al. (2013). The majority of the currently known and well-characterised rubber-degrading bacteria are Gram-positives and belong to the actinobacteria such as species of the genera Nocardia (Tsuchii et al. 1985; Ibrahim et al. 2006; Linh et al. 2017), Streptomyces (Heisey and Papadatos 1995; Jendrossek et al. 1997; Rose et al. 2005; Imai et al. 2011; Chia et al. 2014; Nanthini et al. 2017), Gordonia (Linos et al. 1999; Linos et al. 2002) and Rhodococcus (Watcharakul et al. 2016). Gram-negative rubber-degrading bacteria seem to be less abundant and only one Gram-negative strain with clearly demonstrated rubber-degrading ability was known until recently. This strain is Steroidobacter cummioxidans 35Y (Sharma et al. 2018) (previously Xanthomonas sp. 35Y (Tsuchii and Takeda 1990)) and meanwhile has become one of the best-studied rubber degraders (see below). In the present decade, other Gram-negative rubber-degrading species have been isolated and described such as Rhizobacter gummiphilus (Imai et al. 2010; Imai et al. 2013) or several species of the myxobacteria (Birke et al. 2013). Other Gram-negative rubber-degrading bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas citronellolis and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus) as well as two rubber-degrading Bacillus strains (AF-666 and S10) have been also reported but the evidence for the ability to utilise polyisoprene as the sole source of carbon and energy is yet not fully convincing (Linos et al. 2000; Bode et al. 2000; Bode et al. 2001; Shah et al. 2012; Kanwal et al. 2015) or has been shown to be caused by a mixed culture of a true rubber-degrading Gordonia species and P. aeruginosa AL98 (Arenskötter et al. 2001).

Identification of rubber-degrading bacteria

The majority of the currently described rubber-degrading bacteria produces translucent halos when cultivated on opaque latex-containing solid agar media. The formation of clear zones around the developing colonies of rubber degraders is a consequence of the secretion of rubber-degrading enzymes. These enzymes diffuse into the agar and extracellularly cleave the polymer to low molecular products that can be taken up by the bacteria. The formation of clearing zones indicates that the insoluble polyisoprene latex is converted to smaller products and that the cleavage products, which are also almost insoluble in water, are taken up by the cells and used as a carbon and energy source. Many rubber-degrading Streptomyces strains such as S. coelicolor 1A, S. griseus 1D and Streptomyces sp. K30 but also Gram-negative species such as S. cummioxidans 35Y (Xanthomonas sp. 35Y) and R. gummiphilus NS21 have the ability to form clearing zones on polyisoprene latex agar (Jendrossek et al. 1997; Braaz et al. 2004; Rose et al. 2005; Imai et al. 2011). Interestingly, other potent rubber degraders such as Gordonia polyisoprenivorans VH2, Gordonia westfalica Kb2, Nocardia farcinica, Nocardia nova SH22a and Rhodococcus rhodochrous RPK1 or Rhodococcus pyridinivorans F5 do not form clearing zones on latex agar (Ibrahim et al. 2006; Warneke et al. 2007; Bröker et al. 2008; Luo et al. 2014; Watcharakul et al. 2016; Nawong et al. 2018). Non-clearing zone-forming rubber degraders grow adhesively on the rubber surface and produce no visible clearing zone as shown by electron microscopy (Linos et al. 2000). Adhesively growing strains have specific Mce (mammalian cell entry) transmembrane substrate uptake systems for the incorporation of long-chain polyisoprene cleavage products (for details, see Luo et al. 2014).

Rubber oxygenase RoxA of Steroidobacter cummioxidans 35Y

S. cummioxidans 35Y is the best-studied Gram-negative rubber degrader. Strain 35Y was first described by Tsuchii and Takeda in 1990 (Tsuchii and Takeda 1990) and the authors of this early study already described a “rubber-cleaving activity” in the supernatant of latex-grown 35Y cells and identified aldehyde and keto groups containing cleavage products. Unfortunately, the ecosystem from which strain 35Y was isolated is not known anymore. The only information on the source of the strain found in the publication is “Bacterial strain 35Y, a potent producer of rubber-degrading enzyme, was selected from our culture collection” (Tsuchii and Takeda 1990).

The enzyme responsible for the initial cleavage of rubber by strain 35Y was isolated and biochemically characterised and the corresponding structural gene was cloned and sequenced (Jendrossek and Reinhardt 2003). The rubber-cleaving enzyme of strain 35Y is a 70-kDa dihaem protein that oxidatively cleaves poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) to the C15 compound, 12-oxo-4,8-dimethyltrideca-4,8-diene-1-al (ODTD), as the only major end product (Braaz et al. 2004). The protein was denominated as rubber oxygenase A (RoxA). The two haem groups in RoxA are covalently attached to the apoprotein (c-type haem) via thioether bridges of cysteine sulphur atoms of two haem binding motifs (CxxCH) to the propionate side chains of the haem-porphyrin. The cleavage of polyisoprene to only one major product (ODTD) indicates that RoxA acts processively and cleaves rubber from one end of the polyisoprene chain in an exo-type fashion. 18O2-labeling experiments revealed that RoxA is a dioxygenase (Braaz et al. 2005). The RoxA protein is stable (even at room temperature) and does not need any additional cofactors. Water, adjusted to a neutral pH value, polyisoprene (purified natural rubber latex or synthetic polyisoprene) and the co-substrate dioxygen are the only compounds necessary for efficient cleavage of polyisoprene to ODTD (2.6 U oxygen consumption/mg protein at 37 °C, see Table 1). The two haem groups of RoxA have slightly different midpoint potentials (Eo´) of − 65 mV and of − 130 to − 160 mV (not well resolvable) and in vitro react differently upon the addition of reductants (NADH) (Schmitt et al. 2010). The N-terminal haem group represents the active site and has a dioxygen molecule stably bound in the as isolated state (Seidel et al. 2013). Additional properties of the RoxA protein are discussed in the chapter of the structures of rubber oxygenases below.

Distribution of RoxA homologues

Since the identification of the first roxA gene in S. cummioxidans 35Y, several RoxA homologues have been identified in the translated genomes of genome-sequenced bacteria. Interestingly, RoxAs were found mainly in gamma-proteobacteria such as Myxococcus fulvus, Haliangium ochraceum, Corallococcus coralloides and others but recently also in the beta-proteobacterium Rhizobacter gummiphilus NS21 (Imai et al. 2013) (Fig. 1, Table 2). Expression, purification and biochemical characterisation of several RoxA homologues from myxobacteria (Birke et al. 2013) and from R. gummiphilus (Birke et al. 2018) confirmed that all of them had rubber oxygenase activity and cleaved polyisoprene to the C15 oligoisoprenoid ODTD as the major product, however with a significantly lower specific activity compared to RoxA of strain 35Y (Fig. 2, Table 1). No RoxA homologues have been so far detected in Gram-positive species or in Archaea. Therefore, it seems as if the ability to degrade rubber via a RoxA type rubber oxygenase is restricted to Gram-negative bacteria. Currently, only species of the proteobacteria have been identified as Gram-negative rubber degraders.

Phylogenetic relationship of rubber oxygenases of Gram-negative rubber-degrading species. A multiple sequence alignment of biochemically characterised (red letters) and postulated (black letters) rubber oxygenases was performed using the alignment software MAFFT version 7 and visualised with Archaeopteryx.js. The black branch refers to RoxAs and the blue branch indicates RoxBs. The sequences were identified using a BLASTP search with the RoxA or RoxB sequences of S. cummioxidans 35Y as queries. All shown RoxA and RoxB orthologue sequences have a coverage of ≥ 90% and an identity of > 60% to the query sequence, respectively

Products of polyisoprene cleavage by rubber oxygenases. Cleavage products of polyisoprene latex obtained by incubation with rubber oxygenase as indicated were analysed by HPLC as described previously (Röther et al. 2017b). RoxANS21 (a). RoxBNS21 (b). LcpK30 (c). Synergistic effect on ODTD formation by the simultaneous presence of RoxANS21 and RoxBNS21 (d). Data from Birke et al. (2018) and Birke et al. (2015)

Structure of RoxA35Y

The structure of the 71.5 kDa dihaem rubber oxygenase RoxA of S. cummioxidans 35Y (RoxA35Y) at 1.8 Å resolution revealed a core protein comprising two c-type haem groups that are covalently linked to the protein via the cysteine sulphur atoms of two haem binding motifs (CSAC194H, CASC393H) (Table 1) (Seidel et al. 2013). The RoxA35Y core protein has a distant structural kinship to cytochrome c peroxidases of the CcpA family, for example, the distances and orientations of the two haem groups are similar. However, RoxA35Y is functionally different from CcpAs as it has no peroxidase activity (Schmitt et al. 2010) and is structurally different in the periphery of the molecule by the adoption of several extensions of peripheral loops resulting in a rather “large” protein (71.5 kDa) in comparison to most CcpAs (40–45 kDa). RoxA35Y has an unusually low degree of secondary structures with about two thirds consisting of loops and about one third of α-helices and two short, only 3 residues comprising, β-sheets (Seidel et al. 2013) (Fig. 3a). The C-terminal haem group in RoxA35Y is coordinated by two axial histidine ligands (H394 and H641) (Fig. 3c) and is less important for activity than the N-terminal haem. The latter has H195 as the proximal axial ligand and represents the active site of the enzyme with a dioxygen molecule stably bound as a distal axial ligand (Seidel et al. 2013) (Fig. 3b) similar to haemoglobin. A F317 residue in a distance of approximately 3.7 Å to the haem-bound oxygen assists in the stabilisation of the dioxygen molecule (Seidel et al. 2013; Birke et al. 2012). A substrate tunnel is not visible in the RoxA structure probably because of the hydrophobic nature of the polyisoprene substrate that would require the absence of water in a predicted substrate tunnel. It is assumed that the tunnel is formed after binding of the hydrophobic substrate molecules via flexible apolar/hydrophobic residues forming “hydrophobic brushes” (Seidel et al. 2013). Other RoxA proteins presumably are structurally very similar to RoxA35Y given the high amino acid similarities of RoxAs (63 to 89% identity) and the confirmed rubber oxygenase activity of some of them (Table 1) (Birke et al. 2013) (Birke et al. 2018).

Structure of RoxA from S. cummioxidans 35Y. Cartoon of the structure of RoxA35Y (a). Detailed view into the active site around the N-terminal haem (b). Detailed view around the C-terminal haem (c). Haem cofactors (red) and axial amino acid ligands (green) are shown in sticks. The central iron atom of haem is shown as a pink sphere. The dioxygen molecule bound to the haem iron is shown in blue

Rubber oxygenase B

Recently, a novel type of rubber oxygenase gene with distant relationship to roxA genes was discovered in S. cummioxidans 35Y and in Rhizobacter gummiphilus NS21 sharing amino acid similarities of the gene products of 83% to each other but only of around 36% to currently known RoxAs. The genes were designated as roxB35Y for S. cummioxidans 35Y (Birke et al. 2017) and latA in the case of R. gummiphilus NS21 (Kasai et al. 2017). Based on the high similarities of the properties of the purified RoxB35Y and LatA protein, it became obvious that RoxB35Y and LatA are homologues but substantially differ from all currently known RoxAs in some (but not all) properties. It was therefore suggested to rename LatA as RoxBNS21 (Birke et al. 2018). Strikingly, rubber oxygenase B (RoxB) homologues with molecular masses of around 70 kDa and with amino acid sequence identities of 60–83% to each other were present in other Gram-negative species for which a roxA gene was present in the genome sequence. Furthermore, the amino acid sequences of these RoxB proteins include two typical binding motifs (CxxCH) for covalent attachment of c-type haem groups, a conserved F317 homologue and a MauG motif as present in all currently known RoxAs (Table 1) (Birke et al. 2013). These findings suggest that the characterised and predicted RoxB proteins represent a separate subgroup of RoxA homologues (see also Fig. 1). Indeed, the expression of roxB of S. cummioxidans 35Y and characterisation of the recombinantly expressed and purified protein revealed that RoxB oxidatively cleaved polyisoprene at a high specific activity of ≈ 6 U/mg (Birke et al. 2017). One unit of rubber oxygenase activity corresponds to the consumption of 1 μmol dioxygen per min (for assays of rubber oxygenase activity see (Hiessl et al. 2014; Röther et al. 2017b). In contrast to RoxA35Y, no evidence for a bound dioxygen molecule in the as isolated state was found for RoxB35Y. The most remarkable result was, however, the finding that RoxB of S. cummioxidans 35Y cleaved polyisoprene randomly to a mixture of C20 and higher oligoisoprenoids with terminal aldehyde and keto-functional groups (Fig. 2b), a finding that was recently confirmed for RoxB of R. gummiphilus NS21 (Birke et al. 2018). ODTD, the C15 oligoisoprenoid main cleavage product of RoxA-mediated rubber degradation, was formed only in minor amounts by RoxB35Y or RoxBNS21. These results indicated that RoxBs cleave rubber in an endo-type reaction. Based on the similarities and dissimilarities to RoxAs, all members of the subgroup of RoxA homologues of Gram-negative rubber-degrading species were denominated as RoxB proteins (Birke et al. 2017; Birke et al. 2018).

A remarkable consequence of the different mode of action of RoxB (endo-cleavage versus exo-cleavage of polyisoprene in RoxAs) was the identification of a synergistic effect of the simultaneous presence of both types of rubber oxygenases. The amount of the main cleavage product ODTD produced by RoxA was much higher in in vitro experiments with purified RoxA35Y when RoxB35Y was simultaneously present in comparison to the amount of ODTD produced by RoxA35Y alone (Birke et al. 2017). This finding can be well explained by the formation of free poly/oligoisoprenoid chain ends by the action of RoxB35Y that in turn increases the efficiency of the RoxA35Y-mediated formation of ODTD: natural rubber produced by H. brasiliensis has a high molecular mass of about a million. As a consequence, the number of polyisoprene molecules and polyisoprene chain ends at the surface of rubber particles is rather low in comparison to the number of molecules at the surface of low molecular compounds. Since all currently known RoxA proteins cleave polyisoprene processively from the molecules ends (see above), RoxAs must find and bind to a free polyisoprene chain end to start the cleavage reaction. Because of the low number of polyisoprene chain ends in high molecular weight rubber materials, the efficiency of rubber cleavage by RoxA alone is rather low. However, S. cummioxidans 35Y is one of the fastest growing strains when cultivated on rubber latex (Tsuchii and Takeda 1990) suggesting that S. cummioxidans 35Y has more than only one rubber oxygenase and/or the identification of RoxB35Y can explain how the efficiency of RoxA35Y-mediated polyisoprene cleavage is improved. In the case that RoxB35Y would be the only rubber-cleaving enzyme, this would require the uptake of large isoprenoid molecules with a variable number of isoprene units and this might be difficult for the cells. The synergistic effect of the simultaneous presence of RoxA35Y and RoxB35Y, however, enables S. cummioxidans 35Y to convert rubber extracellularly at high efficiency to just one cleavage product of defined length (ODTD) that can be taken up by only one transport protein and can be used as a source of carbon and energy. Since RoxA35Y and RoxB35Y were shown to be simultaneously expressed in S. cummioxidans 35Y during growth on polyisoprene latex (Birke et al. 2017), the relatively fast growth of S. cummioxidans 35Y on polyisoprene as sole source of carbon and energy can be well explained.

The synergistic action of the two rubber oxygenases of R. gummiphilus NS21 (RoxANS21 and RoxBNS21) was recently experimentally confirmed (Birke et al. 2018). This species is also able to grow on polyisoprene latex as the sole source of carbon and energy and to form clearing zones on opaque latex agar (Imai et al. 2011; Imai et al. 2013). A latA gene was independently identified to be involved in utilisation and cleavage of rubber, but the corresponding LatA protein was not purified and characterised (Kasai et al. 2017). Very recently, it became clear that LatA represents a RoxB homologue and that R. gummiphilus NS21 harboured a second rubber oxygenase, RoxANS21. The RoxANS21 and RoxBNS21 (=LatANS21) proteins of R. gummiphilus NS21 are highly similar to RoxA35Y and RoxB35Y of S. cummioxidans 35Y (Birke et al. 2018) (see Fig. 1 for phylogenetic relationship of RoxAs and RoxBs) and also cleaved polyisoprene synergistically to ODTD as end product. Notably, when the isolated rubber cleavage products generated by RoxBNS21 were used as substrate for RoxANS21, a subsequent HPLC analysis of the products revealed the appearance of a high ODTD peak (Birke et al. 2018). This clearly demonstrated that RoxANS21 is able to use the products of RoxBNS21 as substrate and confirmed the synergistic effect of the two enzymes. Remarkably, almost all genome-sequenced Gram-negative bacteria that have a roxA gene also have a roxB homologue in their genome suggesting that the conjointly appearance of RoxA and RoxB homologues is a common feature of Gram-negative rubber-degrading species. This suggests that all roxA and roxB harbouring Gram-negative species will be potent rubber-degrading bacteria (clear zone formers on opaque latex agar) and will take advantage of the synergistic effect of the simultaneous expression of roxA and roxB homologues on the cleavage of polyisoprene to ODTD as a major cleavage product.

Latex clearing protein

Despite the large number of isolated Gram-positive species with rubber-degrading capabilities (Tsuchii et al. 1985; Heisey and Papadatos 1995; Jendrossek et al. 1997; Imai et al. 2011; Yikmis and Steinbüchel 2012a; Chia et al. 2014), none of the currently genome-sequenced Gram-positive species has a roxA or a roxB gene. This indicates that Gram-positive rubber-degrading species must have a different type of rubber-cleaving enzyme. The first described gene involved in rubber degradation was identified by mutant and complementation analysis of Streptomyces sp. K30, a strain which produces large clearing zones during growth on opaque polyisoprene latex agar (Rose et al. 2005; Yikmis et al. 2008; Yikmis and Steinbüchel 2012b). The transfer of this gene to a mutant specifically defective in clearing zone formation during growth on rubber latex or the transfer to a non-rubber-degrading species of the genus Streptomyces restored or conferred the ability to form clearing zones around the arising colonies during growth in the presence of opaque polyisoprene latex. This gene was denominated as the latex clearing protein (Lcp) gene (Rose et al. 2005). The lcp gene of Streptomyces sp. K30 codes for a protein of ≈ 43 kDa (LcpK30) and the amino acid sequence of LcpK30 reveals no similarities to RoxAs, RoxBs or any other enzyme with known function. For the biochemical properties of Lcps and the structure of LcpK30, see the chapter below.

Since the beginning of this century, the number of genome-sequenced prokaryotes has largely increased. Bioinformatic analysis of these genomes revealed an enormously high number of more than 1000 lcp genes among the Gram-positives suggesting that the ability to utilise polyisoprene compounds is largely distributed among the Gram-positive species. Interestingly, Lcp genes are present in species that either form (e.g. Streptomyces sp. K30, (Rose et al. 2005)) or do not form clear zones on latex agar (Hiessl et al. 2012; Watcharakul et al. 2016). It seems that the synthesis of an Lcp protein is an essential but not the only factor required for the formation of a clearing zone in Gram-positive rubber-degrading species. Not even one Lcp homologue is present in currently genome-sequenced Gram-negative species or in Archaea (August 2018). The strictly separated appearance of either RoxAs/RoxBs in Gram-negative or of Lcps in Gram-positive rubber-degrading species suggests that the ability to cleave polyisoprene evolved independently at least twice.

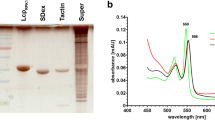

Properties of Lcps

The Lcp proteins of Streptomyces sp. K30, Gordonia polyisoprenivorans VH2, Rhodococcus rhodochrous RPK1 and of Nocardia farcinica NVL3 represent the currently four Lcps that have been purified (Birke and Jendrossek 2014; Hiessl et al. 2014) (Watcharakul et al. 2016; Linh et al. 2017; Oetermann et al. 2018) (status of August 2018); the purified Lcps of Streptomyces sp. K30 (LcpK30), G. polyisoprenivorans VH2 (Lcp1VH2) and R. rhodochrous RPK1 (LcpRPK1) have been biochemically characterised in detail. Lcps have a molecular mass of ≈ 40 to ≈ 46 kDa and thus have roughly only half of the molecular masses of RoxAs or RoxBs (≈ 70–75 kDa). Lcps are not related in amino acid sequence to RoxAs or RoxBs. In contrast to RoxAs and RoxBs that are c-type dihaem proteins, Lcps harbour only one, non-covalently bound b-type haem cofactor as the active site (Birke et al. 2015; Watcharakul et al. 2016; Oetermann et al. 2018). Previous reports on the putative absence of a metal cofactor in LcpK30 (Birke and Jendrossek 2014) or the presence of copper as a cofactor of LcpVH2 (Hiessl et al. 2014) were presumably based on insufficient detection limits or artificial binding of metal ions to the protein. Lcps presumably are also involved in the utilisation of poly(trans-1,4-isoprene) (gutta-percha) (Luo et al. 2014).

The three biochemically well-characterised Lcps and a selection of 492 putative Lcp homologues from the database shared the presence of a conserved domain of unknown function (DUF2236) (Hiessl et al. 2014; Röther et al. 2016). Three amino acid residues of the DUF2236 sequence were almost invariant. These were R164 (conserved in 98.8% of 495 Lcp homologues, numbering according to LcpK30), T168 (99.6%) and H198 (100%) (Röther et al. 2016) (Fig. 4). H198 of LcpK30 (and H195 of Lcp1VH2 (Oetermann et al. 2018)) were identified as the proximal axial haem ligand and R164 and T168 were located close to the distal axial haem ligand K167 ((Ilcu et al. 2017), see below). Residues R164 and H198 (H195 of Lcp1VH2) were essential for activity and T168 was almost essential (2% residual activity of a T168A variant) for activity. Since all three residues participate in the ligation or positioning of the haem in LcpK30, all other proteins with a DUF2236 domain presumably also harbour haem as a cofactor and many of the DUF2236 domain-containing proteins probably might have rubber oxygenase activity.

Alignment of biochemically characterised Lcps. Amino acid sequence alignment of Lcps of Streptomyces sp. K30, R. rhodochrous RPK1 and Lcp1 of G. polyisoprenivorans VH2. Below the alignment, a consensus sequence of 495 Lcp sequences taken from the database is shown. The height of the columns indicates the degree of conservation. The values of conservation (as percentages) for selected strongly conserved residues (highlighted in red) are given below. A 13-residue-long conserved region is indicated by a green bar. Taken from Röther et al. (2016)

Cleavage of poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) by Lcps

All three biochemically characterised Lcps oxidatively cleave polyisoprene randomly to a mixture of oligoisoprenoids with terminal keto and aldehyde groups. Solvent extraction of the polyisoprene latex cleavage products with ethylacetate or methanol gives C20 to ≈ C65 oligoisoprenoids that can be well separated qualitatively by HPLC (Birke et al. 2015; Röther et al. 2016; Röther et al. 2017b) or quantitatively by FPLC (Röther et al. 2017a) (Fig. 2c). The oligoisoprenoids produced from polyisoprene by Lcps are structurally identical to those produced by RoxBs (see above, Fig. 2). However, Lcps and RoxBs are not related proteins. They largely differ from each other in molecular masses, amino acid sequence and cofactor type/content (see above). The C15 oligoisoprenoid ODTD, the main product of RoxA-catalysed polyisoprene cleavage, was identified only in trace amounts in the LcpK30 catalysed reaction. Remarkably, extraction of the Lcp1VH2 derived degradation products with pentane/trichloromethane or other solvents and analysis via GPC and subsequent MALDI-ToF or ESI-MS after derivatisation with Girard-T reagent (Ibrahim et al. 2006; Andler et al. 2018b; Andler et al. 2018a) showed that also very large oligoisoprenoids with > 100 carbon atoms were produced by Lcp1VH2. Together, these data show that Lcps cleave polyisoprene randomly in an endo-type fashion into products of variable length, similar to RoxBs.

Structure of LcpK30

The Lcp protein of Streptomyces sp. K30 (LcpK30) is currently the only rubber oxygenase of a Gram-positive species with a known 3D structure (Ilcu et al. 2017). Because of the amino acid sequence similarities of LcpK30 to the Lcps of G. polyisoprenivorans VH2 (50%) and R. rhodochrous RPK1 (57%), we assume that the two other biochemically characterised Lcps and many other, yet uncharacterised Lcps, have similar structures as LcpK30. The majority of the LcpK30 protein (63%) has an α-helical structure while the other 37% consist of connecting loops (Fig. 5). β-strands or disulphide bridges are absent (no cysteine present in LcpK30). The core of LcpK30 has a classical globin fold consisting of eight helices named A-H as in haemoglobin. Helix D is missing but an additional short helix (L-helix, for Lcp-specific helix) is present between helix E and F. The globin core of LcpK30 embeds the b-haem moiety and reveals high similarities to myoglobin and to the globin-coupled sensor protein of Geobacter sulfurreducens (Pesce et al. 2009). Two additional domains consisting of three (N1-N3) or six (Z1-Z6) α-helices are present in LcpK30 at the N-terminus and the C-terminus, respectively, and form cap-like structures at opposite sites of the globin core (Fig. 5). The specific functions of these additional domains in polyisoprene cleavage are unknown.

Structure of LcpK30. Cartoons of the LcpK30 structure in closed (a) and open (b) form are shown. The porphyrin ring and axial ligands of the central iron are shown as sticks. The LcpK30 core (in green) exhibits a globin fold (helices A-H, and Lcp-specific L-helix, helix D is absent). Lys167 serves as a distal axial ligand to the haem group, effectively preventing access for the substrate O2 in the closed structure (a). The N-terminal extension with helices N1-N3 is shown in blue, the C-terminal extension with helices Z1-Z6 in red. In the presence of imidazole, an open form of LcpK30 was obtained (b) in which Lys167 is replaced by imidazole as a distal axial haem ligand and helix E is split into two fragments. Taken from Ilcu et al. (2017)

Two structures of LcpK30 were determined, one corresponded to the closed state and one represented an open state of the enzyme (Ilcu et al. 2017). The haem group of LcpK30 in the closed structure is ligated by H198 and by K167 as axial ligands. The presence of a lysine as an axial haem ligand is rare in b-type cytochromes. Interestingly, a slightly different structure of LcpK30 was determined when imidazole was present in the crystallisation buffer and pointed to a structural flexibility of LcpK30. In this case, an imidazole molecule of the solvent adopted the place of K167 while the spatial orientations of K167 and T168 were changed (Fig. 5b). The imidazole-bound structure showed an increased accessibility of the haem group, opening a direct access pathway to a cavity at the distal side of the haem group and despite the presence of imidazole this structure is considered to represent an open form of LcpK30.

Two potential reaction mechanisms are currently discussed for the enzymatic cleavage of polyisoprene (see (Ilcu et al. 2017) for details, Fig. 6). However, the postulated intermediates still await for experimental verification.

Mechanistic models of oxidative polyisoprene cleavage by LcpK30. Protons in allylic positions of poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) will be more acidic than those in vinylic positions (a). LcpAK30 catalyses the cleavage of the isoprenoid by inserting both oxygen atoms of an O2 molecule. Possible reaction mechanisms (b). Top: the substrate polymer is threaded into the channel of LcpK30 in the open state (1). O2 binds to the distal axial position of haem iron and a base in the channel, likely Glu148, abstracts a proton from an allylic position, leading to bond formation to an oxygen (2). The second oxygen atom, with increased nucleophilic character, attacks the adjacent carbon (3), leading to the formation of an instable, cyclic dioxetane intermediate (4) that spontaneously rearranges to the cleaved product (5). Bottom: alternatively, the haem-bound dioxygen can be cleaved (2b) to give a substrate epoxide and an oxy-ferryl intermediate (3a). The epoxide bond is cleaved by a nucleophilic attack of the oxy-ferryl-oxygen to the epoxide carbon atom (3b). Cleavage of the iron-oxygen bond (4a) leads to a release of the haem group and of the observed cleavage products (5). Taken from Ilcu et al. (2017)

EPR analysis of rubber oxygenases

The oxidation state of the central iron atom of the haem cofactors in rubber oxygenases and their coordination states with (axial) ligands can be determined by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy (Walker 2004). Ferrous (Fe2+) iron is diamagnetic and therefore does not produce any EPR signals. In contrast, ferric (Fe3+) iron is paramagnetic and dependent on the type of ligands in the neighbourhood of haem, the EPR signals appear at characteristic magnetic fields. So far, only RoxA of S. cummioxidans 35Y (RoxA35Y) has been analysed by EPR (Schmitt et al. 2010; Seidel et al. 2013; Ilcu et al. 2017). One of the two c-type haem groups in RoxA35Y is present in the oxidised (ferric) form and has two axial histidine ligands (H394 and H641). The signals corresponding to this C-terminal haem centre did not change regardless whether substrates (polyisoprene latex, dioxygen) were present or absent (for details see (Schmitt et al. 2010; Seidel et al. 2013)). Therefore, the C-terminal haem centre of RoxA35Y seems to be unimportant for the polyisoprene cleavage reaction. In contrast, the EPR signals of the N-terminal haem centre varied in preparation-dependent forms and in their intensities suggesting that the N-terminal haem centre is the active site and can undergo ferric-ferrous transitions. Only one of the two axial haem positions of the N-terminal haem centre is occupied by an amino acid residue (H195). The other axial haem position is occupied by a stably bound dioxygen molecule (Seidel et al. 2013). Lcp of Streptomyces sp. K30 (LcpK30) is the only Lcp for which a detailed EPR analysis has been performed (Ilcu et al. 2017). In contrast to the active site of RoxA35Y, the (single) b-type haem group of purified LcpK30 in the as isolated state is free of bound dioxygen and is present in the ferric form. However, EPR measurements revealed the presence of two distinguishable haem species: one set of EPR signals corresponded with typical signals of a low spin ferric iron species while the other EPR signals corresponded to high spin ferric signals. Remarkably, the high spin signal disappeared upon the addition of a typical haem ligand such as imidazole; accordingly, in the presence of imidazole, only low spin ferric EPR signals were recorded. This indicated that LcpK30 in solution is present in two conformations: one conformation corresponds with the closed state of LcpK30 in which the haem cofactor has two axial ligands (H198 and K197, see above) and produces typical low spin signals; the other conformation corresponds to the open state, in which the K167 ligation of the haem has been liberated; this haem iron with a free axial position is the source of the high spin signal. The fact that the high spin signal completely disappeared upon the addition of imidazole confirms the accessibility of the haem group by external ligands and identifies this conformation as the open state of LcpK30.

UVvis spectral properties of rubber oxygenases

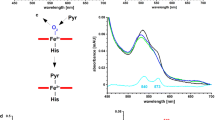

Although the EPR technique is a well-suited tool to study the oxidation state and the chemical environment of haem groups, it requires the availability of expensive equipment that is not present or available in all biochemical laboratories. A more simple technique to study haem-containing proteins is to determine the absorption of these proteins in the range of ≈ 350 to 700 nm (UVvis spectroscopy). Haem-containing proteins produce characteristic spectral absorption patterns in this range (Gouterman 1961) (Fig. 7). Notably, specific absorption characteristics—dependent on which subgroup the investigated rubber oxygenase belongs to—can be recorded by UVvis spectroscopy: RoxAs as isolated generally produce a strong absorption at 407–409 nm (Soret band) and have minor absorptions at 529 nm (β-band) and 573 nm (α-band) in the Q-band region (Fig. 7a). A chemical reduction of RoxAs with dithionite leads to a red shift of the Soret band of about 10 nm to 417–418 nm and the appearance of split α-bands (N-terminal haem at ≈ 549–551 nm/C-terminal haem at ≈ 551–553 nm) and one β-band around 522 nm. In the presence of N-heterocyclic ligands such as imidazole or pyridine, the UVvis spectra of RoxAs resemble that of reduced RoxAs, however, with the acceptation that only the N-terminal α-band emerges (Schmitt et al. 2010). A substantial shift in the absorption of the Soret bands appears by the addition of carbon monoxide (CO) and indicates that CO can be stably bound to RoxAs as isolated. These features—as well as the 3D Structure of RoxA35Y and EPR studies (Seidel et al. 2013)—indicate that the N-terminal haem group of RoxAs rests in a ferrous (Fe2+) state and firmly binds a dioxygen molecule (Fe2+–O2----Fe3+–O2−) that can be replaced by CO similar as in haemoglobin.

UVvis spectra of a RoxA35Y, b RoxB35Y, c LcpRPK1 and d LcpK30. UVvis-absorption spectra of purified rubber oxygenases as indicated were recorded for the as isolated (black lines) and for the chemically reduced (dithionite) proteins (red lines). In the inlay, enlarged spectra in the region of the Q-bands are shown. The numbers indicate the wavelength of the absorption maxima

The Soret bands of the two so far purified and biochemically characterised RoxBs have a 3–5 nm blue-shifted absorption maximum at ≈ 404 nm in the as isolated state compared to their RoxA counterparts (Schmitt et al. 2010; Birke et al. 2013; Birke et al. 2017; Birke et al. 2018) (Fig. 7b). Additionally, weak absorptions at 529 (β-band), 562 (α-band) and 618 nm are detected, the last presumably arises due to a charge transfer (Pond et al. 1999) from a so far unknown residue. Dithionite-reduced RoxBs show only a partial Soret band shift to 418–419 nm and the appearance of a split-α (548, 556 nm) as well as a split β-band (522, 529 nm). Presumably, each signal represents one of the haem groups. The addition of imidazole to the reduced enzymes results in a complete shift of the Soret band to the reduced form; furthermore, the signal at 618 nm diminishes and the α-band at 548 nm shows increased absorbance. After addition of imidazole or CO-buffer to RoxBs as isolated, no significant changes in the UVvis spectrum occurred. The results identify RoxBs as completely oxidised (ferric) enzymes with a 5-fold coordinated N-terminal haem centre in the as isolated states and thus are clearly distinguished from RoxAs.

LcpK30 and LcpVH2 as isolated are characterised by red-shifted Soret bands at ≈ 412 nm compared to RoxAs and RoxBs, β-bands at 532–533 nm and α-bands around 570 nm (Fig. 7d). After reduction by dithionite, the bands shift to 430 nm (Soret band), 532–533 (β-band) and 562–564 nm (α-band). The spectra of LcpK30 and LcpVH2 do not change largely in the presence of imidazole neither in the as isolated nor in the reduced state; only a slight increase in absorbance was observed for the Q-band region for reduced LcpVH2 (Oetermann et al. 2018). The addition of CO to LcpK30 as isolated also has no effect on the UVvis spectrum, in contrast to the dithionite-reduced enzyme. This implies a ferric haem group in Lcps; furthermore, the majority of LcpK30 molecules in solution seems to rest in a bi-axial ligated (closed) as isolated state.

Spectral analysis of the Lcp protein of Rhodococcus rhodochrous RPK1 (LcpRPK1) reveals some distinct properties when compared to LcpK30 and LcpVH2 (Fig. 7c). The Soret, β- and α-band are at 407 nm, 535 nm and (weak) around 570 nm (Watcharakul et al. 2016); an additional feature is present around 645 nm. The addition of CO leads to detectable changes of the UVvis spectrum only after reduction (as in other Lcps). After dithionite reduction, the bands shift to 428 nm (Soret), ≈ 532 (β) and 560–562 nm (α). Notably, the Q-bands of LcpRPK1 are not as defined as seen for other Lcps and the presence of imidazole significantly affects the spectrum of reduced LcpRPK1. These characteristics suggest that LcpRPK1 has a ferric haem group with only one axial amino acid ligand and rests in an open, for ligands accessible state. This interpretation is supported by the detection of prominent changes of the EPR spectrum of LcpRPK1 upon the addition of latex (unpublished data) that was never found for LcpK30.

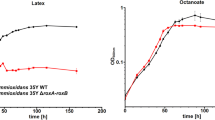

Secretion of rubber oxygenases and incorporation of haem cofactor

The polyisoprene molecules in NR are much too large to be taken up across the cell membrane and therefore must be cleaved extracellularly into smaller molecules. The polypeptides of the rubber oxygenases of Gram-negative bacteria (RoxAs and RoxBs) have typical N-terminal signal peptides to allow a passage across the cell membrane via the sec system although the involvement of the sec system has not been demonstrated experimentally. The incorporation and covalent attachment of the two c-type haem cofactors of RoxAs and RoxBs happens after the transport of the polypeptide across the cell membrane in the periplasmic space. Remarkably, expression of RoxAs (and presumably also of RoxBs) in active form is not possible in recombinant E. coli strains. As soon as the expression of a plasmid-encoded roxA gene is induced (by the addition of an appropriate inducer compound), growth of E. coli (or of recombinant Pseudomonas putida) immediately slows down and stops and no or only trace amounts of RoxA protein can be detected (Hambsch et al. 2010; Birke et al. 2012). Even the additional presence of a plasmid that harbours the complete operon for cytochrome c maturation and that should provide the necessary proteins for posttranslational incorporation and covalent attachment of the c-type haem cofactor could not increase the expression of roxA. The function of the cytochrome c maturation genes was confirmed by successful expression of another c-type cytochrome, the dihaem c-type cytochrome Dhc2 from Geobacter sulfurreducens (Hambsch et al. 2010). A similar phenomenon was previously described for the (unsuccessful) expression of MauG in E. coli (Wang et al. 2003; Wilmot and Davidson 2009). RoxAs and RoxBs both have MauG motifs in their amino acid sequences. We assume that MauG (a cytrochrome c peroxidase-related protein with two c-type haems as cofactor; MauG is required for the biosynthesis of the tryptophan tryptophylquinone cofactor of methylamine dehydrogenase) and related c-type cytochromes with MauG motifs employ a different cytochrome c incorporation/maturation system that is absent or non-functional in E. coli. For these reasons, rubber oxygenases of Gram-negative bacteria (RoxAs and/or RoxBs) were generally expressed in S. cummioxidans 35Y. The chromosomal roxA and/or roxB genes were deleted and replaced by the rubber oxygenase gene of interest under an inducible promoter. This procedure allowed a reproducible expression of large amounts of active RoxAs or RoxBs (Hambsch et al. 2010; Birke et al. 2012; Birke et al. 2017; Birke et al. 2018). The ∆roxA35Y-roxB35Y double deletion mutant of S. cummioxidans 35Y can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Lcps incorporate the b-type haem group intracellularly and the correctly folded, active holoenzyme is secreted via the TAT-secretion system. This has been shown experimentally for the Lcp protein of Streptomyces sp. K30 (Yikmis et al. 2008) and presumably accounts for many if not all other Lcps given the widespread presence of the twin-arginine motif in the signal peptides of Lcps. The overexpression of full length lcp from Streptomyces sp. K30 in E. coli in active form was also not successful (Yikmis et al. 2008; Yikmis and Steinbüchel 2012b) but was fairly possible in S. cummioxidans 35Y (Birke and Jendrossek 2014). In contrast, intracellular expression of lcps in recombinant E. coli (by removing the signal peptide) without substantial growth inhibition by the induction of lcp expression resulted in good yields of active protein (Hiessl et al. 2014; Birke et al. 2015; Röther et al. 2016; Andler and Steinbüchel 2017; Oetermann et al. 2018).

Biotechnological application of rubber-degrading microorganisms and their rubber oxygenases

Despite the ubiquitous presence of rubber-degrading microorganisms in most ecosystems on earth, the biodegradation process of products with rubber as a main constituent is very slow. Even under optimal laboratory conditions, it takes weeks or even months until a substantial weight loss of solid rubber is obtained. Moreover, most rubber products contain additives such as antioxidants and other stabilisers; furthermore, the polyisoprene molecule chains of most rubber items are cross-linked by sulphur bridges (vulcanised rubber). These modifications inhibit microorganisms and/or their rubber oxygenases (Berekaa et al. 2000). Furthermore, the biodegradation process is limited to the surface of the rubber materials because neither microorganisms nor rubber oxygenases can penetrate the water-insoluble material. These drawbacks potentially can be overcome by appropriate pre-treatments of the rubber items, such as grinding to increase the available surface, solvent extraction to remove antioxidants/stabilisers, and chemical or biological treatments to break the sulphur bridges. These necessities surely will largely increase the costs of the biotechnological process. For these reasons, the simple combustion of rubber items is at present more promising compared to the sophisticated biodegradation of rubber because a costly pre-treatment is not necessary and the released heat-energy can be at least partially used for production of electricity.

On the other hand, rubber oxygenases, in particular RoxAs, are rather stable enzymes and can be used for the biotechnological production of oligoisoprenoids as fine chemicals of defined length (C15 to ≈ C65) from rubber materials. Such oligoisoprenoids are highly active due to their keto and aldehyde functionalities and can be used as building blocks in chemical reactions for the synthesis of compounds with more complex structures. For the first examples of laboratory production of oligoisoprenoids using Lcp, see Andler and Steinbüchel (2017) and Andler et al. (2018b). Individual oligoisoprenoids of defined length (C15 to ≈ C65) can be isolated from RoxB- or Lcp-derived oligoisoprenoid mixtures by FPLC as described in Röther et al. (2017a). The C15-oligoisoprenoid ODTD can be more efficiently obtained by a combination of RoxAs with RoxBs or of RoxAs with Lcps instead of RoxAs alone because the increase in the number of oligoisoprene chain ends by RoxB/Lcp leads to a more efficient RoxA catalysis (see part on synergistic effect above).

Last not least, rubber oxygenases could be used to “bioprint” rubber surfaces. For example, the exposure of (selected areas of) a rubber surface to rubber oxygenases will introduce keto/aldehyde functions to the rubber surface only at these selected areas that can further react (“be developed”) with other chemicals in a second step thereby creating a (potentially visible) pattern on the surface of the rubber item. For such applications, only minor amounts of rubber oxygenases and only a very limited degree of degradation of the rubber materials would be necessary.

Outlook

The properties of the currently biochemically characterised rubber oxygenases produced by Gram-negative species (RoxAs and RoxBs) and by Gram-positive rubber degraders (Lcps) are summarised in this overview. While RoxAs specifically cleave polyisoprene to only one major cleavage products (C15 isoprenoid ODTD), RoxBs and Lcps cleave rubber randomly to a mixture of oligoisoprenoids of different length. Up to now (summer 2018), no example of the presence of a roxA gene in a Gram-positive species was identified in the database. This is surprising at least for the clear zone-forming Gram-positive rubber-degrading species as RoxAs exert a synergistic effect on the efficiency of Lcp-catalysed polyisoprene cleavage. In the case of adhesively growing rubber-degrading species, the close association of the bacteria with the polymeric substrate might compensate this disadvantage: the uptake system for rubber cleavage products is more efficient when dilution of the product concentration by diffusion is less pronounced because of the direct contact with the substrate. This might be the explanation why Gram-negative rubber degraders and Gram-positive, adhesively on rubber growing strains, grow faster on rubber than not adhesively growing Gram-positive rubber degraders.

Due to the ubiquitous presence of compounds harbouring isoprene units, it is reasonable to predict that rubber-cleaving enzymes will be also present at least in some Archaea and in fungi. Reports on rubber-utilising fungi are frequent but to the best of our knowledge, publications on rubber-utilising Archaea are missing at present. It will be interesting to determine if rubber-degrading Archaea/fungi also have RoxAs/RoxBs or Lcps, or if they employ different, yet undiscovered types of rubber-cleaving enzymes for the initial cleavage of polyisoprene.

References

Andler R, Altenhoff A-L, Mäsing F, Steinbüchel A (2018a) In vitro studies on the degradation of poly(cis-1,4-isoprene). Biotechnol Prog 78:4543–4899. https://doi.org/10.1002/btpr.2631

Andler R, Hiessl S, Yücel O, Tesch M, Steinbüchel A (2018b) Cleavage of poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) rubber as solid substrate by cultures of Gordonia polyisoprenivorans. New Biotechnol 44:6–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbt.2018.03.002

Andler R, Steinbüchel A (2017) A simple, rapid and cost-effective process for production of latex clearing protein to produce oligopolyisoprene molecules. J Biotechnol 241:184–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.12.008

van Beilen JB, Poirier Y (2007a) Establishment of new crops for the production of natural rubber. Trends Biotechnol 25:522–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.08.009

van Beilen JB, Poirier Y (2007b) Guayule and Russian dandelion as alternative sources of natural rubber. Crit Rev Biotechnol 27:217–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/07388550701775927

Berekaa MM, Linos A, Reichelt R, Keller U, Steinbüchel A (2000) Effect of pretreatment of rubber material on its biodegradability by various rubber degrading bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett 184(2):199–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1097(00)00048-3

Berthelot K, Lecomte S, Estevez Y, Peruch F (2014) Hevea brasiliensis REF (Hev b 1) and SRPP (Hev b 3): an overview on rubber particle proteins. Biochimie 106:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2014.07.002

Berthelot K, Peruch F, Lecomte S (2016) Highlights on Hevea brasiliensis (pro)hevein proteins. Biochimie 127:258–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2016.06.006

Birke J, Hambsch N, Schmitt G, Altenbuchner J, Jendrossek D (2012) Phe317 is essential for rubber oxygenase RoxA activity. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:7876–7883. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02385-12

Birke J, Jendrossek D (2014) Rubber oxygenase and latex clearing protein cleave rubber to different products and use different cleavage mechanisms. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:5012–5020. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01271-14

Birke J, Röther W, Jendrossek D (2018) Rhizobacter gummiphilus NS21 has two rubber oxygenases (RoxA and RoxB) acting synergistically in rubber utilization. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-9341-6

Birke J, Röther W, Jendrossek D (2017) RoxB is a novel type of rubber oxygenase that combines properties of rubber oxygenase RoxA and latex clearing protein (Lcp). Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e00721–e00717. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00721-17

Birke J, Röther W, Jendrossek D (2015) Latex clearing protein (Lcp) of Streptomyces sp. strain K30 is a b-type cytochrome and differs from rubber oxygenase A (RoxA) in its biophysical properties. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:3793–3799. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00275-15

Birke J, Röther W, Schmitt G, Jendrossek D (2013) Functional identification of rubber oxygenase (RoxA) in soil and marine myxobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:6391–6399. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02194-13

Bode HB, Kerkhoff K, Jendrossek D (2001) Bacterial degradation of natural and synthetic rubber. Biomacromolecules 2:295–303. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm005638h

Bode HB, Zeeck A, Plückhahn K, Jendrossek D (2000) Physiological and chemical investigations into microbial degradation of synthetic poly(cis-1,4-isoprene). Appl Environ Microbiol 66:3680–3685

Braaz R, Armbruster W, Jendrossek D (2005) Heme-dependent rubber oxygenase RoxA of Xanthomonas sp. cleaves the carbon backbone of poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) by a dioxygenase mechanism. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:2473–2478. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.5.2473-2478.2005

Braaz R, Fischer P, Jendrossek D (2004) Novel type of heme-dependent oxygenase catalyzes oxidative cleavage of rubber (poly-cis-1,4-isoprene). Appl Environ Microbiol 70:7388–7395. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.12.7388-7395.2004

Bröker D, Dietz D, Arenskötter M, Steinbüchel A (2008) The genomes of the non-clearing-zone-forming and natural-rubber- degrading species Gordonia polyisoprenivorans and Gordonia westfalica harbor genes expressing Lcp activity in Streptomyces strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:2288–2297. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02145-07

Chengalroyen MD, Dabbs ER (2013) The biodegradation of latex rubber: a minireview. J Polym Environ 21:874–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-013-0593-z

Chia K-H, Nanthini J, Thottathil GP, Najimudin N, Haris MRHM, Sudesh K (2014) Identification of new rubber-degrading bacterial strains from aged latex. Polym Degrad Stab 109:354–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.07.027

Cornish K (2001) Biochemistry of natural rubber, a vital raw material, emphasizing biosynthetic rate, molecular weight and compartmentalization, in evolutionarily divergent plant species. Nat Prod Rep 18:182–189

Cornish K, Wood D, Windle J (1999) Rubber particles from four different species, examined by transmission electron microscopy and electron-paramagnetic-resonance spin labeling, are found to consist of a homogeneous rubber core enclosed by a contiguous, monolayer biomembrane. Planta 210:85–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004250050657

Epping J, van Deenen N, Niephaus E, Stolze A, Fricke J, Huber C, Eisenreich W, Twyman RM, Pruefer D, Gronover CS (2015) A rubber transferase activator is necessary for natural rubber biosynthesis in dandelion. Nat Plants 1:15048. https://doi.org/10.1038/NPLANTS.2015.48

Fudou R, Jojima Y, Iizuka T, Yamanaka S (2002) Haliangium ochraceum gen. nov., sp. nov. and Haliangium tepidum sp. nov.: novel moderately halophilic myxobacteria isolated from coastal saline environments. J Gen Appl Microbiol 48:109–116

Gouterman M (1961) Spectra of porphyrins. J Mol Spectrosc 6:138–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-2852(61)90236-3

Hambsch N, Schmitt G, Jendrossek D (2010) Development of a homologous expression system for rubber oxygenase RoxA from Xanthomonas sp. J Appl Microbiol 109:1067–1075. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04732.x

Heisey RM, Papadatos S (1995) Isolation of microorganisms able to metabolize purified natural rubber. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:3092–3097

Hiessl S, Boese D, Oetermann S, Eggers J, Pietruszka J, Steinbüchel A (2014) Latex clearing protein-an oxygenase cleaving poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) rubber at the cis double bonds. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:5231–5240. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01502-14

Hiessl S, Schuldes J, Thuermer A, Halbsguth T, Broeker D, Angelov A, Liebl W, Daniel R, Steinbüchel A (2012) Involvement of two latex-clearing proteins during rubber degradation and insights into the subsequent degradation pathway revealed by the genome sequence of Gordonia polyisoprenivorans strain VH2. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:2874–2887. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.07969-11

Ibrahim E, Arenskötter M, Luftmann H, Steinbüchel A (2006) Identification of poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) degradation intermediates during growth of moderately thermophilic actinomycetes on rubber and cloning of a functional lcp homologue from Nocardia farcinica strain E1. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:3375–3382. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.72.5.3375-3382.2006

Ilcu L, Röther W, Birke J, Brausemann A, Einsle O, Jendrossek D (2017) Structural and functional analysis of latex clearing protein (Lcp) provides insight into the enzymatic cleavage of rubber. Sci Rep 7:6179. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05268-2

Iizuka T, Jojima Y, Fudou R, Yamanaka S (1998) Isolation of myxobacteria from the marine environment. FEMS Microbiol Lett 169:317–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1097(98)00473-X

Imai S, Ichikawa K, Kasai D, Masai E, Fukuda M (2010) Isolation and characterization of rubber-degrading bacteria. J Biotechnol 150:237–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.09.089

Imai S, Ichikawa K, Muramatsu Y, Kasai D, Masai E, Fukuda M (2011) Isolation and characterization of Streptomyces, Actinoplanes, and Methylibium strains that are involved in degradation of natural rubber and synthetic poly(cis-1,4-isoprene). Enzym Microb Technol 49:526–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enzmictec.2011.05.014

Imai S, Yoshida R, Endo Y, Fukunaga Y, Yamazoe A, Kasai D, Masai E, Fukuda M (2013) Rhizobacter gummiphilus sp. nov., a rubber-degrading bacterium isolated from the soil of a botanical garden in Japan. J Gen Appl Microbiol 59:199–205

Jendrossek D, Reinhardt S (2003) Sequence analysis of a gene product synthesized by Xanthomonas sp. during growth on natural rubber latex. FEMS Microbiol Lett 224:61–65

Jendrossek D, Tomasi G, Kroppenstedt RM (1997) Bacterial degradation of natural rubber: a privilege of actinomycetes? FEMS Microbiol Lett 150:179–188

Kanwal N, Shah AA, Qayyum S, Hasan F (2015) Optimization of pH and temperature for degradation of tyre rubber by Bacillus sp. strain S10 isolated from sewage sludge. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 103:154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2015.05.009

Kasai D, Imai S, Asano S, Tabata M, Iijima S, Kamimura N, Masai E, Fukuda M (2017) Identification of natural rubber degradation gene in Rhizobacter gummiphilus NS21. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 81:614–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/09168451.2016.1263147

Li YZ, Hu W, Zhang YQ, Qiu ZJ, Zhang Y, Wu BH (2002) A simple method to isolate salt-tolerant myxobacteria from marine samples. J Microbiol Methods 50:205–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-7012(02)00029-5

Linh DV, Huong NL, Tabata M, Imai S, Iijima S, Kasai D, Anh TK, Fukuda M (2017) Characterization and functional expression of a rubber degradation gene of a Nocardia degrader from a rubber-processing factory. J Biosci Bioeng 123:412–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2016.11.012

Linos A, Berekaa MM, Steinbüchel A, Kim KK, Sproer C, Kroppenstedt RM (2002) Gordonia westfalica sp. nov., a novel rubber-degrading actinomycete. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52:1133–1139. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-52-4-1133

Linos A, Reichelt R, Keller U, Steinbüchel A (2000) A gram-negative bacterium, identified as Pseudomonas aeruginosa AL98, is a potent degrader of natural rubber and synthetic cis-1, 4-polyisoprene. FEMS Microbiol Lett 182:155–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1097(99)00583-2

Linos A, Steinbüchel A, Spröer C, Kroppenstedt RM (1999) Gordonia polyisoprenivorans sp. nov., a rubber-degrading actinomycete isolated from an automobile tyre. Int J Syst Bacteriol 49(Pt 4):1785–1791. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-49-4-1785

Luo Q, Hiessl S, Poehlein A, Daniel R, Steinbüchel A (2014) Insights into the microbial degradation of rubber and gutta-percha by analysis of the complete genome of Nocardia nova SH22a. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3895–3907. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00473-14

Nanthini J, Ong SY, Sudesh K (2017) Identification of three homologous latex-clearing protein (lcp) genes from the genome of Streptomyces sp. strain CFMR 7. Gene 628:146–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2017.07.039

Nawong C, Umsakul K, Sermwittayawong N (2018) Rubber gloves biodegradation by a consortium, mixed culture and pure culture isolated from soil samples. Braz J Microbiol 49:481–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjm.2017.07.006

Oetermann S, Vivod R, Hiessl S, Hogeback J, Holtkamp M, Karst U, Steinbüchel A (2018) Histidine at position 195 is essential for association of heme-b in Lcp1VH2. Earth Syst Environ 2:5–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-018-0041-2

Pesce A, Thijs L, Nardini M, Desmet F, Sisinni L, Gourlay L, Bolli A, Colettas M, Van Doorslaer S, Wan X, Alam M, Ascenzi P, Moens L, Bolognesi M, Dewilde S (2009) HisE11 and HisF8 provide bis-histidyl heme hexa-coordination in the globin domain of Geobacter sulfurreducens globin-coupled sensor. J Mol Biol 386:246–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.023

Pond AE, Roach MP, Sono M, Rux AH, Franzen S, Hu R, Thomas MR, Wilks A, Dou Y, Ikeda-Saito M, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Woodruff WH, Boxer SG, Dawson JH (1999) Assignment of the heme axial ligand(s) for the ferric myoglobin (H93G) and heme oxygenase (H25A) cavity mutants as oxygen donors using magnetic circular dichroism. Biochemistry 38:7601–7608. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi9825448

Rose K, Steinbüchel A (2005) Biodegradation of natural rubber and related compounds: recent insights into a hardly understood catabolic capability of microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:2803–2812. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.6.2803-2812.2005

Rose K, Tenberge KB, Steinbüchel A (2005) Identification and characterization of genes from Streptomyces sp. strain K30 responsible for clear zone formation on natural rubber latex and poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) rubber degradation. Biomacromolecules 6:180–188. https://doi.org/10.1021/bm0496110

Röther W, Austen S, Birke J, Jendrossek D (2016) Molecular insights in the cleavage of rubber by the latex-clearing-protein (Lcp) of Streptomyces sp. strain K30. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:6593–6602. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02176-16

Röther W, Birke J, Grond S, Beltran JM, Jendrossek D (2017a) Production of functionalized oligo-isoprenoids by enzymatic cleavage of rubber. Microb Biotechnol 43:1238–1433. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-7915.12748

Röther W, Birke J, Jendrossek D (2017b) Assays for the detection of rubber oxygenase activities. Bio-Protocol 7:1–14. https://doi.org/10.21769/BioProtoc.2188

Schiefer A, Schmitz A, Schäberle TF, Specht S, Lämmer C, Johnston KL, Vassylyev DG, König GM, Hoerauf A, Pfarr K (2012) Corallopyronin a specifically targets and depletes essential obligate Wolbachia endobacteria from filarial nematodes in vivo. J Infect Dis 206:249–257. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jis341

Schmidt T, Lenders M, Hillebrand A, van Deenen N, Munt O, Reichelt R, Eisenreich W, Fischer R, Prüfer D, Gronover CS (2010) Characterization of rubber particles and rubber chain elongation in Taraxacum koksaghyz. BMC Biochem 11:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2091-11-11

Schmitt G, Seiffert G, Kroneck PMH, Braaz R, Jendrossek D (2010) Spectroscopic properties of rubber oxygenase RoxA from Xanthomonas sp., a new type of dihaem dioxygenase. Microbiology (Reading, England) 156:2537–2548. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.038992-0

Seidel J, Schmitt G, Hoffmann M, Jendrossek D, Einsle O (2013) Structure of the processive rubber oxygenase RoxA from Xanthomonas sp. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:13833–13838. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1305560110

Shah AA, Hasan F, Shah Z, Kanwal N, Zeb S (2013) Biodegradation of natural and synthetic rubbers: a review. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 83:145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2013.05.004

Shah AA, Hasan F, Shah Z, Mutiullah HA (2012) Degradation of polyisoprene rubber by newly isolated Bacillus sp. AF-666 from soil. Prikl Biokhim Mikrobiol 48:45–50

Sharma V, Siedenburg G, Birke J, Mobeen F, Jendrossek D, Srivastava TP (2018) Metabolic and taxonomic insights into the Gram-negative natural rubber degrading bacterium Steroidobacter cummioxidans sp. nov., strain 35Y. PLoS One 13(5):e0197448 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197448

Tsuchii A, Suzuki T, Takeda K (1985) Microbial degradation of natural rubber vulcanizates. Appl Environ Microbiol 50:965–970

Tsuchii A, Takeda K (1990) Rubber-degrading enzyme from a bacterial culture. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:269–274

Wadeesirisak K, Castano S, Berthelot K, Vaysse L, Bonfils F, Peruch F, Rattanaporn K, Liengprayoon S, Lecomte S, Bottier C (2017) Rubber particle proteins REF1 and SRPP1 interact differently with native lipids extracted from Hevea brasiliensis latex. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1859:201–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.11.010

Walker FA (2004) Models of the bis-histidine-ligated electron-transferring cytochromes. Comparative geometric and electronic structure of low-spin ferro- and ferrihemes. Chem Rev 104:589–615. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr020634j

Wang Y, Graichen ME, Liu A, Pearson AR, Wilmot CM, Davidson VL (2003) MauG, a novel diheme protein required for tryptophan tryptophylquinone biogenesis. Biochemistry 42:7318–7325. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi034243q

Warneke S, Arenskötter M, Tenberge KB, Steinbüchel A (2007) Bacterial degradation of poly(trans-1,4-isoprene) (gutta percha). Microbiology (Reading, England) 153:347–356. https://doi.org/10.1099/mic.0.2006/000109-0

Watcharakul S, Röther W, Birke J, Umsakul K, Hodgson B, Jendrossek D (2016) Biochemical and spectroscopic characterization of purified latex clearing protein (Lcp) from newly isolated rubber degrading Rhodococcus rhodochrous strain RPK1 reveals novel properties of Lcp. BMC Microbiol 16:92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-016-0703-x

Wilmot CM, Davidson VL (2009) Uncovering novel biochemistry in the mechanism of tryptophan tryptophylquinone cofactor biosynthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol 13:469–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.06.026

Yikmis M, Arenskoetter M, Rose K, Lange N, Wernsmann H, Wiefel L, Steinbüchel A (2008) Secretion and transcriptional regulation of the latex-clearing protein, lcp, by the rubber-degrading bacterium Streptomyces sp. strain K30. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:5373–5382. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01001-08

Yikmis M, Steinbüchel A (2012a) Historical and recent achievements in the field of microbial degradation of natural and synthetic rubber. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:4543–4551. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00001-12

Yikmis M, Steinbüchel A (2012b) Importance of the latex-clearing protein (Lcp) for poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) rubber cleavage in Streptomyces sp. K30. Microbiologyopen 1:13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.3

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to D J (JE 152 18-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethic approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jendrossek, D., Birke, J. Rubber oxygenases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103, 125–142 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-9453-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-9453-z