Abstract

Summary

We examined fracture patients’ understanding of “high” fracture risk after they were screened through a post-fracture secondary prevention program and educated about their risk verbally, numerically, and graphically. Our findings suggest that messages about fracture risk are confusing to patients and need to be modified to better suit patients’ needs.

Introduction

The aim of this study was to examine fracture patients’ understanding of high risk for future fracture.

Methods

We conducted an in-depth qualitative study in patients who were high risk for future fracture. Patients were screened through the Osteoporosis Exemplary Care Program where they were educated about fracture risk: verbally told they were “high risk” for future fracture, given a numerical prompt that they had a >20 % chance of future fracture over the next 10 years, and given a visual graph highlighting the “high risk” segment. This information about fracture risk was also relayed to patients’ primary care physicians (PCPs) and specialists. Participants were interviewed at baseline (within six months of fracture) and follow-up (after visit with a PCP and/or specialist) and asked to recall their understanding of risk and whether it applied to them.

Results

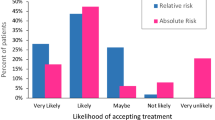

We recruited 27 patients (20 females, 7 males) aged 51–87 years old. Fractures were sustained at the wrist (n = 7), hip (n = 7), vertebrae (n = 2), and multiple or other locations (n = 11). While most participants recalled they had been labeled as “high risk” (verbal cue), most were unable to correctly recall the other elements of risk (numerical, graphical). Further, approximately half of the patients who recalled they were high risk did not believe that high risk applied, or had meaning, to them. Participants also had difficulty explaining what they were at risk for.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that health care providers’ messages about fracture risk are confusing to patients and that these messages need to be modified to better suit patients’ needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johansson H, Borgstrom F, Strom O, McCloskey E (2009) FRAX and its applications to clinical practice. Bone 44:734–743

Bogoch ER, Cheung AM, Elliot-Gibson VIM, Gross DK (2010) Preventing the second hip fracture: addressing osteoporosis in hip fracture patients. In: Waddell JP (ed) Fractures of the proximal femur. Elsevier, Maryland Heights, MO

Leslie WD, Lix LM, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey E, Kanis JA (2010) Independent clinical validation of a Canadian FRAX tool: fracture prediction and model calibration. J Bone Miner Res 25:2350–2358

Siminoski K, Leslie WD, Frame H, Hodsman A, Josse RG, Khan A, Lentle BC, Levesque J, Lyons DJ, Tarulli G, Brown JP (2005) Recommendations for bone mineral density reporting in Canada. Can Assoc Radiol J 56:178–188

Papaioannou A, Morin SM, Cheung AM, Atkinson S, Brown JP, Feldman S, Hanley DA, Hodsman A, Jamal SA, Kaiser SM, Kvern B, Siminoski K, Leslie WD, for the Scientific Advisory Council of Osteoporosis Canada (2010) 2010 Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ DOI:10.1503/cmaj.100771.

Leslie WD, Berger C, Langsetmo L, Lix LM, Adachi JD, Hanley D, Ioannidis G, Josse R, Kovacs C, Towheed TE, Kaiser SM, Olszynski WP, Prior J, Jamal S, Kreiger N, Goltzman D, Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study Research Group (2011) Construction and validation of a simplified fracture risk assessment tool for Canadian women and men: results from the CaMos and Manitoba cohorts. Osteoporos Int 22:1873–1883

Langley A (2003) What does it mean when the risk assessment says 4.73 × 10−5? NSW Public Health Bull 14:166–167

Irvine EJ (2004) Measurement and expression of risk: optimizing decision strategies. Am J Med 117:2S–7S

Anonymous (2005) Taking care of yourself is risky business. Harv Heart Lett 2005:4–5

Sale JEM, Beaton DE, Sujic R, Bogoch ER (2010) ‘If it was osteoporosis, I would have really hurt myself.’ Ambiguity about osteoporosis and osteoporosis care despite a screening program to educate fracture patients. J Eval Clin Pract 16:590–596

Sale JEM, Beaton DE, Bogoch ER, Elliot-Gibson V, Frankel L (2010) The BMD muddle: understanding the disconnect between bone densitometry results and perception of bone health. J Clin Densitom 13:370–378

Cadarette SM, Beaton DE, Gignac MA et al (2007) Minimal error in self-report of having had DXA, but self-report of its results was poor. J Clin Epidemiol 60:1306–1311

Kingwell E, Prior JC, Ratner PA, Kennedy SM (2010) Direct-to-participant feedback and awareness of bone mineral density testing results in a population-based sample of mid-aged Canadians. Osteoporos Int 21:307–319

Siris ES, Gehlbach S, Adachi J, Boonen S, Chapurlat RD, Compston J, Cooper C, Delmas P, Diez-Perez A, Hooven F, LaCroix AZ, Netelenbos JC, Pfeilschifter J, Rossini M, Roux C, Saag K, Sambrook P, Silverman S, Watts NB, Wyman A, Greenspan SL (2011) Failure to perceive increased risk of fracture in women 55 years and older: the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Osteoporos Int 22:27–35

Giangregorio L, Dolovich L, Cranney A et al (2009) Osteoporosis risk perceptions among patients who have sustained a fragility fracture. Patient Educ Couns 74:213–220

Schwarzer R, Lippke S, Luszczynska A (2011) Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the health action process approach (HAPA). Rehab Psychol 56:161–170

Schwandt TA (2001) Dictionary of qualitative inquiry. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, 281 p

Sokolowski R (2000) Introduction to phenomenology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 238 p

Morse JM (1994) Designing funded qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) Handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, pp 220–235

Giorgi A (2008) Concerning a serious misunderstanding of the essence of the phenomenological method in psychology. J Phenomenol Psychol 39:33–58

Bogoch ER, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Jamal SA, Josse RG, Murray TM (2006) Effective initiation of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment for patients with a fragility fracture in an orthopaedic environment. J Bone Joint Surg (Am Vol) 88(1):25–34

Papaioannou A, Leslie WD, Morin S, Atkinson S, Brown J, Cheung AM, Cranney AB, Feldman S, Hanley DA, Hodsman A, Jamal AS, Kaiser SM, Kvern B, Siminoski KSACOC (2010) 2010 Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada. Can Med Assoc J 182:1864–1873

Lipkus IM (2007) Numeric, verbal, and visual formats of conveying health risks: suggested best practices and future recommendations. Med Decis Mak 27:696–713. doi:10.1177/0272989X07307271

Jasper MA (1994) Issues in phenomenology for researchers of nursing. J Adv Nurs 19:309–314

Foley KA, Foster SA, Meadows ES, Baser O, Long SR (2007) Assessment of the clinical management of fragility fractures and implications for the new HEDIS osteoporosis measure. Med Care 45:902–906

Sampsel SL, MacLean CH, Pawlson LG, Hudson SS (2007) Methods to develop arthritis and osteoporosis measures: a view from the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Clin Exp Rheumat 25:22–27

(2008) NVivo, version Qualitative Solutions and Research Pty. Ltd, Victoria

Giorgi A (1997) The theory, practice, and evaluation of the phenomenological method as a qualitative research procedure. J Phenomenol Psychol 28:235–260

Crotty M (1996) Phenomenology and nursing research. Churchill Livingstone, South Melbourne

Malterud K (2001) Qualitative research: standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 358:483–488. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6

Kvale S (1996) Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Giorgi A (1989) Some theoretical and practical issues regarding the psychological phenomenological method. Saybrook Rev 7:71–85

Wertz FJ (2005) Phenomenological research methods for counseling psychology. J Couns Psychol 52:167–177

Polkinghorne DE (1989) Phenomenological research methods. In: Valle RS, Halling S (eds) Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology. Plenum Press, New York, pp 41–60

Creswell JW (1998) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Douglas F, Petrie KJ, Cundy T, Horne A, Gamble G, Grey A (2012) Differing perceptions of intervention thresholds for fracture risk: a survey of patients and doctors. Osteoporos Int 23:2135–2140

Grover ML, Edwards FD, Chang Y-HH, Cook CB, Behrens MC, Dueck AC (2014) Fracture risk perception study: patient self-perceptions of bone health often disagree with calculated fracture risk. Womens Health Issues 24-1:e69–e75

Gilchrist AL, Cowan N, Naveh-Benjamin M (2008) Working memory capacity for spoken sentences decreases with adult ageing: recall of fewer but not smaller chunks in older adults. Memory 16:773–787

Taconnat L, Clarys D, Vanneste S, Bouazzaoui B, Isingrini M (2007) Aging and strategic retrieval in a cued-recall test: the role of executive functions and fluid intelligence. Brain Cogn 64:1–6

Cansino S, Hernandez-Ramos E, Trejo-Morales P (2012) Neural correlates of source memory retrieval in young, middle-aged and elderly adults. Biol Psychol 90:33–49

Meadows LM, Mrkonjic LA, O’Brien MD, Tink W (2007) The importance of communication in secondary fragility fracture treatment and prevention. Osteoporos Int 18:159–166

Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M (1999) The effect of risk communication on risk perceptions: the significance of individual differences. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 25:94–100

Sale JEM, Gignac M, Hawker G, Frankel L, Beaton D, Bogoch E, Elliot-Gibson V (2012) Patients reject the concept of fragility fracture—a new understanding based on fracture patients’ communication. Osteoporos Int 23:2829–2834

Sale JEM, Gignac MA, Hawker G, Beaton D, Bogoch E, Webster F, Frankel L, Elliot-Gibson V (2014) Non-pharmacological strategies used by patients at high risk for future fracture to manage fracture risk—a qualitative study. Osteoporos Int 25:281–288

Meadows LM, Mrkonjic LA, Petersen KMA, Lagendyk LE (2004) After the fall: women’s views of fractures in relation to bone health at midlife. Women Health 39:47–62

Akesson K, Marsh D, Mitchell PJ, McLellan AR, Stenmark J, Pierroz DD, Kyer C, Cooper C, IOF Fracture Working Group (2013) Capture the fracture: a best practice framework and global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporos Int 24:2135–2152

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP—119522). Joanna Sale was, in part, funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Salary Award and by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Osteoporosis Strategy. Views expressed are those of the researchers and not the Ministry.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sale, J.E.M., Gignac, M.A., Hawker, G. et al. Patients do not have a consistent understanding of high risk for future fracture: a qualitative study of patients from a post-fracture secondary prevention program. Osteoporos Int 27, 65–73 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3214-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3214-y