Abstract

Depressive symptoms and urinary symptoms are both highly prevalent in pregnancy. In the general population, an association is reported between urinary symptoms and depressive symptoms. The association of depressive and urinary symptoms has not yet been assessed in pregnancy. In this study, we assessed (1) the prevalence of depressive symptoms, over-active bladder (OAB) syndrome, urge urinary incontinence (UUI) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI) during and after pregnancy using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) and the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) and (2) the association of depressive symptoms with urinary incontinence and over-active bladder syndrome during and after pregnancy, controlling for confounding socioeconomic, psychosocial, behavioural and biomedical factors in a cohort of healthy nulliparous women. Our data show a significant increase in prevalence of depressive symptoms, UUI, SUI and OAB during pregnancy and a significant reduction in prevalence of depressive symptoms, SUI and OAB after childbirth. UUI prevalence did not significantly decrease after childbirth. In univariate analysis, urinary incontinence and the OAB syndrome were significantly associated with a CES-D score indicative of a possible clinical depression at 36 weeks gestation. However, after adjusting for possible confounding factors, only the OAB syndrome remained significantly associated (OR 4.4 [1.8–10.5]). No association was found between depressive and urinary symptoms at 1 year post-partum. Only OAB was independently associated with depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Possible explanations for this association are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lifetime risk of depressive symptoms in women (5.9–21.3%) is about twice that in men and symptoms often start in the childbearing years [1–3]. Prevalence rates of 10–25% during pregnancy [4–9] and of 6–16% post-partum are reported [5, 6, 8, 10–12]. Prevalence rates vary because of the diversity of populations and diagnostic methodology. Most researchers found higher rates during pregnancy than after childbirth [5, 6, 8]. Urogenital symptoms are also more prevalent in pregnancy than in the general population. Prevalence rates of 9–50% have been reported for urinary incontinence (UI) during first pregnancy and 34–95% for frequency and urgency symptoms (over-active bladder [OAB] syndrome) [13, 14]. Strong associations are found between depressive symptoms, urinary incontinence and over-active bladder syndrome in non-pregnant women [15–19]. Whilst the relationship of depressive symptoms and urinary symptoms has not yet been explored in pregnancy, several factors have been found to be associated with depressive symptoms in a general, pregnant and post-partum population. These factors include biomedical factors such as obesity, age, chronic pain (like back pain), previous depressive symptoms [12, 20, 21], behavioural factors like excessive use of alcohol, smoking, lack of leisure time physical exercise and socioeconomic factors like unemployment and low job satisfaction [5, 7, 22]. Psychosocial factors, such as poorer social support, stressful life events and personality features have also been found related to depressive symptoms [11, 22–25].

The aim of this study was to (1) analyse the prevalence of depressive symptoms and urinary symptoms during and after pregnancy and (2) assess the association of urinary symptoms with depressive symptoms, controlling for psychosocial, behavioural, socioeconomic and biomedical factors during and after pregnancy.

Materials and methods

Study population

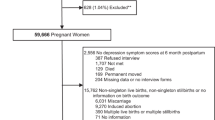

Between January 2002 and July 2003, 1,366 nulliparous pregnant women from 10 urban midwifery practices in the center of The Netherlands were approached to take part in a prospective longitudinal cohort study assessing pelvic floor problems, sexuality and back pain during first pregnancy until 1 year after delivery. All nulliparous pregnant women received information about the study from the midwives. After 1 week, the women were approached by phone and asked if they wanted to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were a singleton low risk pregnancy and sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language.

One hundred and twenty-two women were excluded due to having a twin pregnancy (n = 2), miscarriage (n = 13) or insufficient knowledge of the Dutch language (107). Thus, 1,244 women met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 672 (54%) decided to participate in the study. The most common reasons for refusal were lack of time and the intensity and intrusiveness of the questions. The present study is a separate analysis of data collected from the larger study. The Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht approved the study. All participants signed an informed consent form.

Data collection

To assess the prevalence rates at different points in time of depressive symptoms, stress urinary incontinence (SUI), urge urinary incontinence (UUI) and over-active bladder (OAB) syndrome, we used data obtained from all respondents of questionnaires sent at 12 and 36 weeks gestation and 3 and 12 months post-partum. In addition, we analysed data obtained from the questionnaires sent at 36 weeks gestation and 12 months after delivery to assess the possible association between urinary symptoms and depression. We did so because the prevalence of urinary symptoms peak in the third trimester and because pelvic floor symptoms, occurring in pregnancy and persisting 1 year after delivery, may be associated with depression at this time [26].

Depressive symptoms were investigated using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). This scale is developed for use in non-psychiatric populations and gives an impression of depressive symptoms [27, 28]. The total score ranges from 0 to 60; a higher score corresponds with more depressive symptoms. A cut-off score of 16 is frequently used as an indication of a possible clinical depression. We refer in this study to women who scored B16 on the CES-D as having depressive symptoms.

Urinary symptoms were assessed with the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) [29, 30]. The UDI is a validated, standardised questionnaire, translated in Dutch. This questionnaire consists of 19 questions about urogenital symptoms and the experienced discomfort of these symptoms. We looked specifically at self-reported urge and stress urinary incontinence and over-active bladder syndrome. Although the UDI also consists of questions on prolapse, obstructive micturition and pain and heaviness in the pelvic area, these symptoms have not been linked to depression in current literature. Therefore, these questions were not used in the present study. We followed the definitions of the International Continence Society (ICS) [31]. Urge incontinence was determined by a positive answer to the question: “Do you experience urine leakage related to the feeling of urgency?” Stress incontinence was determined by a positive answer to the question: “Do you experience urine leakage related to physical activity, coughing or sneezing?” Over-active bladder syndrome was determined when both of the following questions were answered positively: “Do you experience frequent urination?” and “Do you experience a strong feeling of urgency to empty your bladder?”

Validated questionnaires were used to assess potential confounding variables. The Dutch Personality Questionnaire (DPQ) contains 133 statements, which are divided into 7 domains: inadequacy, social inadequacy, rigidity, hostility, egoism, dominance and self-esteem [32]. The higher the score, the more these characteristics are part of the subject’s personality. Personality traits are stable and this questionnaire was completed at 24 weeks gestation for logistic reasons. The Maudsley Marital Questionnaire (MMQ) was used to measure the subjective emotional and sexual relationship of the woman with her partner [33]. The MMQ consists of 15 questions, of which 10 concern emotional aspects (range 0–80) and 5 concern sexual aspects (range 0–40) of the relationship. The higher the score, the worse this specific aspect of the relationship is perceived. In addition, the questionnaires addressed biomedical and socioeconomic variables.

Biomedical factors included length and weight at 36 weeks gestation and 1 year after delivery, age at time of delivery, the presence of a chronic illness or back pain and the use of medication. Data on mode of delivery and pregnancy-related complications (hypertensive disorders, premature delivery, growth retardation and vaginal blood loss) were obtained from the case files of obstetricians and midwifes. Data on length and weight were transformed into a body mass index (BMI = weight/(height)2). Socioeconomic factors consisted of level of education, marital state, employment and job satisfaction. For practical reasons, the education level was dichotomised into high school or less and more than high school. Marital state was dichotomised into married and unmarried/divorced. Behavioural factors we studied were whether participants smoked, used alcohol or were involved in leisure time physical activity in early pregnancy. In addition, women were able to add comments to the standard questions.

Statistical analyses

Changes in prevalence of depressive symptoms, UUI, SUI and OAB between 6 and 12 weeks gestation and between 36 weeks gestation and 3 and 12 months after delivery was determined using the McNemar tests. Possible variables associated with depressive symptoms, including urinary symptoms, were analysed in women that responded to the questionnaire at 36 weeks gestation and 1 year after delivery. Women with and without CES-D B16 were compared in univariate analyses using the independent samples t-test for continuous variables and chi-squared test for categorical variables. The relationship between depressive symptoms (CES-D _16) (dependent variable), urinary symptoms and potential confounders was assessed using multivariate logistic regression analysis (stepwise forward method) to assess whether urinary symptoms remained associated with depressive symptoms.

Only significantly associated variables in univariate analyses (p < 0.05) were put in the model. Odds ratios (Exp (B)) for continuous variables were calculated when appropriate. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used to establish the goodness of fit of the model. A p value of >0.05 indicates that the model provides a valid representation of data. All analyses were performed with the SPSS for Windows 11.5.

Results

Of the 672 women who started in the study at 12 weeks gestation, 642 (95%) women responded to the personality questionnaire sent at 24 weeks gestation. The questionnaires at 36 weeks gestation and 3 and 12 months after delivery were answered by 511 (76%), 503 (75%) and 509 (76%) women, respectively. The average age at delivery was 30.0 years (standard deviation (SD) 3.6 years). Average BMI at 36 weeks gestation was 27.9 kg/m2 (SD 4.1 kg/m2). The percentage of women whose education stopped after high school was 52.7%. None of the women were breast-feeding 1 year after delivery. The percentage of women who did not have a spontaneous vaginal delivery was 33.9%. Pregnancy-related complications were reported in 18.3%. In our series, urinary tract infection was not mentioned by any of the women.

The prevalence rates of depressive symptoms, UUI, SUI and OAB at different points in time during and after pregnancy are shown in Table 1. The increase in prevalence during pregnancy (from 12 to 36 weeks gestation) and decrease in prevalence after pregnancy (from 36 weeks gestation to 12 months after delivery) of all symptoms, except urge urinary incontinence, was statistically significant in the McNemar tests (p < 0.05). The increase in prevalence of urge incontinence during pregnancy was significant; however, the seemingly decrease after childbirth was not significant. Factors significantly associated with depressive symptoms at 36 weeks gestation in univariate analyses and in multivariate logistic regression model are shown in Table 2. Many factors were significantly associated in univariate analysis; however, in logistic regression only (social) inadequacy (personality traits), worse sexual relationship with the partner, not being involved in leisure time physical activity, pregnancy-related complications and OAB syndrome remained independently associated with depressive symptoms. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test provided a p value of 0.214, which indicates a proper goodness of fit for this model. Explained variance in this model (R 2) is 40.9%. At 1 year post-partum, no significant association was found between depressive and urinary symptoms in the chi-squared tests; therefore, no logistic regression analysis was performed.

Discussion

In our study, we set out to analyse the prevalence of depressive and urinary symptoms during and after pregnancy and to assess the possible association of urinary symptoms with depression, whilst controlling for psychosocial, behavioural, socioeconomic and biomedical factors. We showed a significant increase in prevalence of depressive symptoms, UUI, SUI and OAB during pregnancy and a significant reduction in the prevalence of depressive symptoms, SUI and OAB after childbirth (p < 0.05). The prevalence of UUI did not significantly decrease after childbirth. In univariate analysis, UUI, SUI and the OAB syndrome was significantly associated with a CES-D score of B16 at 36 weeks gestation. However, after adjusting for possible confounding factors, only the OAB syndrome remained significantly associated. At 1 year after delivery, no association was found between urinary incontinence, OAB syndrome and depressive symptoms.

In non-pregnant women, an association is reported between depression and urinary incontinence, especially urge incontinence, and over-active bladder syndrome with and without urge incontinence [15–19]. These studies mainly used univariate statistics and did not account for potential confounding factors. Our univariate analysis also showed that urinary incontinence and over-active bladder syndrome were significantly associated with depressive symptoms. However, in multivariate analysis, we did not find an association between depressive symptoms and stress or urge urinary incontinence during or after pregnancy. On the other hand, we did find an independent significant relation between depressive symptoms and over-active bladder syndrome at 36 weeks gestation, though not 1 year after delivery. In a research in a non-pregnant population, several explanations are suggested. Firstly, urinary incontinence as a chronic disorder may lead to depressive symptoms. The finding that depression at 1 year after delivery was not associated with urinary symptoms does not support this explanation. Secondly, it is suggested that psychological factors might influence urgency and detrusor instability [34]. Thirdly, a mutual pathologic origin of urinary incontinence and depression is proposed: both are suggested to be caused by the reduction of serotonin [15, 35]. This suggestion is at the least dubious because serotonergic depletion as the suggested aetiology in depression has been seriously questioned [36]. Furthermore, the therapeutic effect of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of depression is only slightly better than placebo [37].

In a pregnant population, several other explanations can be considered. First, during the third trimester of pregnancy, the increase in cardiac output, increasing size of the uterus with compression of the bladder and sleep disturbances may all contribute to an increased voiding frequency. Secondly, the definition used for over-active bladder syndrome (combination of urgency and frequency) has been developed for use in a non-pregnant population. Because the majority of women will have frequency and urgency symptoms as part of their normal third trimester pregnancy, it is questionable if the diagnosis of OAB in pregnancy has the same meaning and impact as OAB in non-pregnant women. The strength of this study is that we used a prospective, longitudinal design with validated questionnaires in a large number of healthy nulliparous women. By measuring not only urogenital symptoms and depressive symptoms, but also psychosocial, behavioural, socioeconomic and biomedical factors, we were able to perform solid multivariate analysis techniques on the associations between bladder symptoms and depression.

Our study has also some potential drawbacks that need to be discussed. First, because of the observational, epidemiological design of the study, all information gathered through the questionnaires is subjective. We used a symptom-based definition of urinary symptoms recommended by the ICS [31]. Although we could rule out, to a certain extend, urinary tract infection as potential confounding factor for urinary symptoms from the records of the midwife or gynecologist, we were unable to confirm the reported symptoms by means of a clinical diagnosis. However, the sensitivity of clinical tests like the stress test and also urodynamic investigation in relation to urogenital symptoms is still under debate [38, 39]. Our data have to be interpreted from a symptom-based point of view, which is most often the best there is to get out of epidemiological studies. It would be worthwhile to test our findings in a clinical setting, although the use of urodynamics during pregnancy in healthy women may turn out to be a difficult ethical question. Secondly, we had a moderate participation rate. Due to the quantity and intimate nature of the questions on sexuality and pelvic floor discomfort, the response rate was 54%. However, the prevalence rates of pelvic floor problems and back pain found in this cohort are in concordance with prevalence rates in other studies and the obstetrical outcome (mode of delivery, birth weight, etc.) of the study population was similar to that of comparable women registered in The Netherlands Perinatal Registry 2001 [13, 40, 41]. In addition, the percentage of women scoring above the cut-off score of 16 on the CES-D is similar to that found in a large American study among pregnant women [7]. Finally, the associations we found between psychosocial, behavioural, socioeconomic and biomedical factors at 36 weeks gestation have all been reported before in ante-natal and post-natal study populations [5, 7, 21, 22, 42–45]. So, the chance that our results are biased by the moderate participation rate is low. A third limitation is that we did not have information on urogenital and depressive symptoms before pregnancy. We decided not to ask about previous symptoms because of the risk of recall bias. Longstanding pre-pregnancy depressive disorders or urogenital symptoms may affect the prevalence rate recorded in pregnancy, but it is questionable if it would affect the associations we studied. Our main conclusion that there is no association between UUI, SUI and depressive symptoms during and after pregnancy was reached after multivariate adjustment in which many factors were accounted for. Finally, the prevalence of depressive symptoms was measured with the CES-D and diagnosis of depression could therefore differ from diagnosis obtained through interview following the DSM-IV criteria. However, the CES-D is a widely used questionnaire with adequate sensitivity and specificity [46], gives a good indication of depressive symptoms and is very suitable for large cohort studies.

Conclusion

We found significantly higher rates of depressive symptoms, SUI and OAB syndrome during pregnancy than after childbirth. After controlling for other associated factors, we found an independent association between depressive symptoms and the OAB syndrome in pregnancy but not with urinary incontinence. This association between OAB syndrome and depressive symptoms is lost after pregnancy, so it is likely that pregnancy-related factors have confounded this association. In general practice, this information on the natural course of the OAB syndrome, and its lack in causing major depressive symptoms after childbirth, can be used to counsel women who are confronted with these problems during pregnancy.

References

Bijl RV, Ravelli A, van Zessen G (1998) Prevalence of psychiatric disorder in the general population: results of The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 33:587–595

Ohayon MM, Priest RG, Guilleminault C, Caulet M (1999) The prevalence of depressive disorders in the United Kingdom. Biol Psychiatry 45:300–307

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS (1994) Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51:8–19

Chung TK, Lau TK, Yip AS, Chiu HF, Lee DT (2001) Antepartum depressive symptomatology is associated with adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes. Psychosom Med 63:830–834

Da Costa D, Larouche J, Dritsa M, Brender W (2000) Psychosocial correlates of prepartum and postpartum depressed mood. J Affect Disord 59:31–40

Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J (2001) Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. BMJ 323:257–260

Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FC, Barry KL (2003) Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetrics settings. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 12:373–380

Gotlib IH, Whiffen VE, Mount JH, Milne K, Cordy NI (1989) Prevalence rates and demographic characteristics associated with depression in pregnancy and the postpartum. J Consult Clin Psychol 57:269–274

Holcomb WL Jr, Stone LS, Lustman PJ, Gavard JA, Mostello DJ (1996) Screening for depression in pregnancy: characteristics of the Beck Depression Inventory. Obstet Gynecol 88:1021–1025

Josefsson A, Angelsioo L, Berg G, Ekstrom CM, Gunnervik C, Nordin C, Sydsjo G (2002) Obstetric, somatic, and demographic risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 99:223–228

Nielsen Forman D, Videbech P, Hedegaard M, Dalby Salvig J, Secher NJ (2000) Postpartum depression: identification of women at risk. BJOG 107:1210–1217

Chaudron LH, Klein MH, Remington P, Palta M, Allen C, Essex MJ (2001) Predictors, prodromes and incidence of postpartum depression. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 22:103–112

van Brummen HJ, Bruinse HW, van der Bom JG, Heintz AP, van de Vaart CH (2005) How do the prevalences of urogenital symptoms change during pregnancy? Neurourol Urodyn 25:135–139

Viktrup L (2002) The risk of lower urinary tract symptoms five years after the first delivery. Neurourol Urodyn 21:2–29

Zorn BH, Montgomery H, Pieper K, Gray M, Steers WD (1999) Urinary incontinence and depression. J Urol 162:82–84

Buchsbaum GM, Chin M, Glantz C, Guzick D (2002) Prevalence of urinary incontinence and associated risk factors in a cohort of nuns. Obstet Gynecol 100:226–229

Chiverton PA, Wells TJ, Brink CA, Mayer R (1996) Psychological factors associated with urinary incontinence. Clin Nurse Spec 10:229–233

Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, Abrams P, Herzog AR, Corey R, Hunt TL, Wein AJ (2003) Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol 20:327–336

Melville JL, Delaney K, Newton K, Katon W (2005) Incontinence severity and major depression in incontinent women. Obstet Gynecol 106:585–592

Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, Mens JM, van Dieen JH, Wuisman PI, Ostgaard HC (2004) Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I: terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence. Eur Spine J 13:575–589

Carter AS, Baker CW, Brownell KD (2000) Body mass index, eating attitudes, and symptoms of depression and anxiety in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Psychosom Med 62:264–270

Jurado D, Gurpegui M, Moreno O, Fernandez MC, Luna JD, Galvez R (2005) Association of personality and work conditions with depressive symptoms. Eur Psychiatry 20:213–222

Seguin L, Potvin L, St-Denis M, Loiselle J (1995) Chronic stressors, social support, and depression during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 85:583–589

O’Hara MW (1986) Social support, life events, and depression during pregnancy and the puerperium. Arch Gen Psychiatry 43:569–573

Brugha TS, Sharp HM, Cooper SA, Weisender C, Britto D, Shinkwin R, Sherrif T, Kirwan PH (1998) The Leicester 500 Project. Social support and the development of postnatal depressive symptoms, a prospective cohort survey. Psychol Med 28:63–79

Thorp JM Jr, Norton PA, Wall LL, Kuller JA, Eucker B, Wells E (1999) Urinary incontinence in pregnancy and the puerperium: a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181:266–273

Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas 1:385–401

Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Van Limbeek J (1997) Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in The Netherlands. Psychol Med 27:231–235

Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS, McClish D, Fantl JA (1994) Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program in Women (CPW) Research Group. Qual Life Res 3:291–306

van der Vaart CH, de Leeuw JR, Roovers JP, Heintz AP (2003) Measuring health-related quality of life in women with urogenital dysfunction: the urogenital distress inventory and incontinence impact questionnaire revisited. Neurourol Urodyn 22:97–104

Abrams P CL, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, van Kerrebroeck P, Victor A, Wein A (2002) The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187:116–126

Luteijn F, Starren J, Van Dijk H (2000) Handleiding bij de Nederlandse persoonlijkheids vragenlijst.-herz. uitg. Swets Test Publishers, Lisse

Arrindell WA, Schaap C (1985) The Maudsley Marital Questionnaire (MMQ): an extension of its construct validity. Br J Psychiatry 147:295–299

Hunt J (1996) Psychological approaches to the management of sensory urgency and idiopathic detrusor instability. Br J Urol 77:339–341

Steers WD, Lee KS (2001) Depression and incontinence. World J Urol 19:351–357

Lacasse JR, Leo J (2005) Serotonin and depression: a disconnect between the advertisements and the scientific literature. PLoS Med 2:e392

Moncrieff J, Wessely S, Hardy R (2004) Active placebos versus antidepressants for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD003012

Chaliha CBJ, Monga A, Stanton SL, Sultan AH (2000) Pregnancy and delivery: a urodynamic viewpoint. BJOG 107:1354–1359

Ryhammer AM, Laurberg S, Djurhuus JC, Hermann AP (1998) No relationship between subjective assessment of urinary incontinence and pad test weight gain in a random population sample of menopausal women. J Urol 159:800–803

Nederland SPR (2005) Perinatale zorg in Nederland 2001

van Brummen HJ, Bruinse HW, van de Pol G, Heintz AP, van der Vaart CH (2005) Defecatory symptoms during and after the first pregnancy: prevalences and associated factors. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 17:224–230

Kitamura T, Shima S, Sugawara M, Toda MA (1996) Clinical and psychosocial correlates of antenatal depression: a review. Psychother Psychosom 65:117–123

Watson JP, Elliott SA, Rugg AJ, Brough DI (1984) Psychiatric disorder in pregnancy and the first postnatal year. Br J Psychiatry 144:453–462

McMahon C, Barnett B, Kowalenko N, Tennant C (2005) Psychological factors associated with persistent postnatal depression: past and current relationships, defence styles and the mediating role of insecure attachment style. J Affect Disord 84:15–24

Robson KM, Brant HA, Kumar R (1981) Maternal sexuality during first pregnancy and after childbirth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 88:882–889

Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR (1995) Symptoms versus a diagnosis of depression: differences in psychosocial functioning. J Consult Clin Psychol 63:90–100

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

van de Pol, G., van Brummen, H.J., Bruinse, H.W. et al. Is there an association between depressive and urinary symptoms during and after pregnancy?. Int Urogynecol J 18, 1409–1415 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-007-0371-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-007-0371-3