Abstract

Background

On April 1, 2004, BCG (bacille Calmette-Guérin), a tuberculosis (TB) control vaccine, was discontinued in all but four high-risk communities in Alberta. To confirm the safety of vaccine withdrawal, and for future planning, the annual risk of infection (ARI) was determined in preschool First Nations children.

Methods

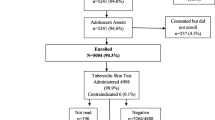

First Nations children born into reserve communities in Alberta between April 1, 1998 and March 31, 2004, and still living on reserve in 2004–2005, were identified. Health centre TB histories were validated by cross-referencing the birth cohort with the provincial TB Registry. Children that were not BCG vaccinated and not known to be tuberculin skin test (TST) positive underwent a TST. Birth cohort children were grouped as follows: (i) BCG vaccinated; (ii) BCG non-vaccinated, no TST; (iii) BCG non-vaccinated, TST; (iv) BCG vaccination status unknown. The ARI was calculated and the age and community characteristics of the groups were compared.

Results

There were 8,447 children in the 6-year birth cohort, 4,699 (55.6%) vaccinated, 2,696 (31.9%) non-vaccinated, and 1,052 (12.5%) whose vaccination status was unknown. Of the non-vaccinated children, 1,921 (71.3%) were tested and only 2 were TST positive. No other TST positive, BCG non-vaccinated children were identified in the TB Registry cross-match. The prevalence of infection in 2004–2005 was 0.1% and the ARI was 0.03%. The community risk of TB exposure was comparable in tuberculin-tested and non-tested BCG non-vaccinated children.

Conclusion

In low BCG-uptake First Nations communities in Alberta, the ARI is low and it is safe to withdraw BCG.

Résumé

Contexte

Le 1er avril 2004, le vaccin BCG (bacille Calmette-Guérin) contre la tuberculose a été abandonné partout en Alberta sauf dans quatre communautés à risque élevé. Afin de confirmer que le retrait du vaccin ne posait aucun danger et de planifier les programmes futurs, nous avons calculé le risque annuel d’infection (RAI) chez les enfants d’âge préscolaire membres des Premières nations.

Méthode

Nous avons répertorié les enfants membres des Premières nations nés dans les réserves de l’Alberta entre le 1er avril 1998 et le 31 mars 2004 qui vivaient toujours dans des réserves en 2004–2005. Nous avons ensuite validé les dossiers sur la tuberculose des centres sanitaires en faisant des recoupements entre la cohorte de naissance et le registre provincial sur la tuberculose. Les enfants n’ayant pas reçu le BCG et n’ayant pas eu un résultat positif à un test de sensibilité cutané à la tuberculine (TST) ont été soumis à un TST. Les enfants de la cohorte de naissance ont été regroupés comme suit: i) vaccinés par le BCG; ii) non vaccinés par le BCG, sans TST; iii) non vaccinés par le BCG, avec TST; iv) statut vaccinal inconnu par rapport au BCG. Nous avons calculé le RAI, puis comparé l’âge et les caractéristiques communautaires des groupes.

Résultats

Sur les 8 447 enfants dans la cohorte de naissance de six ans, 4 699 (55,6 %) étaient vaccinés, et 2 696 (31,9 %) ne l’étaient pas; le statut vaccinal des autres (1 052, soit 12,5 %) était inconnu. Sur les enfants non vaccinés, 1 921 (71,3 %) avaient été testés, et 2 seulement étaient positifs pour le TST. Aucun autre enfant positif pour le TST et non vacciné par le BCG n’a été identifié par recoupement avec le registre de la tuberculose. La prévalence de l’infection en 2004–2005 était de 0,1 %, et le RAI était de 0,03 %. Le risque communautaire d’exposition à la tuberculose était comparable chez les enfants non vaccinés par le BCG, qu’ils aient subi ou non le test cutané à la tuberculine.

Conclusion

Dans les communautés des Premières nations de l’Alberta où les taux de vaccination par le BCG sont faibles, le risque annuel d’infection est faible également, et le retrait du BCG ne pose pas de danger.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Wherrett GJ. The Miracle of the Empty Beds. A History of Tuberculosis in Canada. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1977.

Hopkins JW. BCG vaccination in Montreal. Amer Rev Tuberc 1941;43:581–99.

Ferguson RG, Simes AB. BCG vaccination of Indian infants in Saskatchewan. Tubercle 1949;30:5–11.

Working Group on Tuberculosis, Medical Services Branch. National Tuberculosis Elimination Strategy. Ottawa, ON, June 10, 1992.

Scheifele D, Law B, Jadavji T on behalf of IMPACT. Disseminated bacille Calmette-Guérin infection: Three recent Canadian cases. CCDR 1998;24–9:1–9.

Cunningham JA, Kellner JD, Bridge PJ, Trevenen CL, McLeod DR, Davies HD. Disseminated bacille Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant with a novel deletion in the interferon-gamma receptor gene. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2000;4:791–94.

Deeks SL, Clark M, Scheifele DW, Law BJ, Dawar M, Ahmadipour N et al. Serious adverse events associated with bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine in Canada. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005;24:538–41.

Long R, Whittaker D, Russell K, Kunimoto D, Reid R, Fanning A et al. Pediatric tuberculosis in Alberta First Nations (1991–2000): Outbreaks and the protective effect of Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. Can J Public Health 2004;95:249–55.

International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Criteria for discontinuation of vaccination programmes using Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) in countries with a low prevalence of tuberculosis. Tuberc Lung Dis 1994;75:179–81.

Menzies RI. Tuberculin skin testing. In: Reichman LB, Hershfield ES (Eds.), Tuberculosis. A Comprehensive International Approach, 2nd edition. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc., 2000.

Clark M, Riben P, Nowgesic E. The association of housing density, isolation and tuberculosis in Canadian First Nations communities. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:940–45.

Nyboe J. Interpretation of tuberculosis infection age curves. Bull World Health Org 1957;17:319–39.

Rieder HL. Methodologic issues in the estimation of the tuberculosis problem from tuberculin surveys. Tuberc Lung Dis 1995;76:114–21.

Rieder HL. Annual risk of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 2005;25:181–85.

Ghon A. The Primary Lung Focus of Tuberculosis in Children. London, UK: Churchill, 1916.

Sutherland I. Recent studies in the epidemiology of tuberculosis, based on the risk of being infected with tubercle bacilli. Adv Tuberc Res 1976;19:1–63.

Styblo K. The relationship between the risk of tuberculous infection and the risk of developing infectious tuberculosis. Bull Int Union Tuberc 1985;60:117–19.

Davies JW. BCG vaccination–its place in Canada. Can J Public Health 1965;56:244–52.

Frappier A. Some aspects of BCG vaccination programs in Canada. Can J Public Health 1960;51:435–45.

Houston S, Fanning A, Soskolne CL, Fraser N. The effectiveness of bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination against tuberculosis. Am J Epidemiol 1990;131:340–48.

Young TK, Hershfield ES. A case-control study to evaluate the effectiveness of mass neonatal BCG vaccination among Canadian Indians. Am J Public Health 1986;76:783–86.

Young TK. BCG vaccination among Canadian Indians and Inuit: The epidemiologic bases for policy decision. Can J Public Health 1985;76:124–29.

National Advisory Committee on Immunization. Statement on Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. CCDR 2004;30(ACS-5):1–12.

Long R. Tuberculosis control in Alberta: A federal, provincial and regional public health partnership. Can J Public Health 2002;93:264–66.

Clark M, Vynnycky E. The use of maximum likelihood methods to estimate the risk of tuberculous infection and disease in a Canadian First Nations population. Int J Epidemiol 2004;33:477–84.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study was presented in poster format to the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease North American Regional meeting in Vancouver, February 24–26, 2005. p ]Supported by: First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, Alberta Region, and Alberta Health and Wellness.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jacobs, S., Warman, A., Roehrig, N. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection in First Nations Preschool Children in Alberta. Can J Public Health 98, 116–120 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404321

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03404321