Abstract

Introduction

Health economic models are increasingly important in funding decisions but most are based on data, which may therefore not represent the general population. We sought to establish the potential of real-world data available within the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and linked Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) to determine comprehensive healthcare utilisation and costs as input variables for economic modelling.

Methods

A cohort of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) who first saw a gastroenterologist in 2008 or 2009, and with 3 years of data before and after their appointment, was created in the CPRD. Primary care, outpatient, inpatient, prescription and colonoscopy data were extracted from the linked CPRD and HES. The appropriate cost to the NHS was attached to each event. Total and stratified annual healthcare utilisation rates and costs were calculated before and after the gastroenterology appointment with distribution parameters. Absolute differences were calculated with 95 % confidence intervals.

Results

Total annual healthcare costs over 3 years increase by £935 (95 % CI £928–941) following a gastroenterology appointment for IBS. We derived utilisation and cost data with parameter distributions stratified by demographics and time. Women, older patients, smokers and patients with greater comorbidity utilised more healthcare resources, which generated higher costs.

Conclusions

These linked datasets provide comprehensive primary and secondary care data for large numbers of patients, which allows stratification of outcomes. It is possible to derive input parameters appropriate for economic models and their distributions directly from the population of interest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Accurate costs from the health service perspective can be precisely attached to the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and linked Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data at an individual level, and these data can be used to calculate accurate total healthcare utilisation rates and costs. |

There are sufficient data available to allow multiple stratification that reflects patient heterogeneity. |

The outcomes generated from these methods at either an individual or cohort level can be used directly as input parameters for further economic modelling, which will enhance healthcare policy and decision making. |

1 Introduction

Health economic evaluations are becoming increasingly important in the decisions made regarding healthcare provision and policy. In many healthcare settings, funding for a service, drug or intervention is dependent on demonstrating its cost effectiveness. These evaluations require complete and detailed longitudinal data for large numbers of patients regarding the course of their health conditions, the consequences and the costs [1]. Historically, this has been difficult to retrieve or compile. The increase in electronic collection of routine healthcare data means real-world data are becoming more available. Real-world evidence from electronic health records represents actual clinical practice and patient heterogeneity in a way not often reflected within randomised controlled trials (RCTs) [2, 3]. The large number of patients available for study provides the opportunity for subgroup stratification and assessment of rare diseases and outcomes, which is usually not possible with RCT data. An additional benefit is the many years of data available for each patient [2].

Until recently, datasets have allowed analysis of only one aspect of patient care. These have included care from a single provider, only primary care, only inpatient or outpatient hospital care, or mortality. Recent developments in data linkage now allow analysis of the majority of healthcare accessed by patients in England across domains paid for by the National Health Service (NHS) [4, 5]. Detailed data for calculating healthcare cost according to the UK NHS payment and reimbursement system are also publically available [6, 7]. Combining these data offers new potential to assess complete utilisation and cost of healthcare from the perspective of the UK NHS as payer.

This study assesses the feasibility of using linked electronic health records to calculate the cost of healthcare utilisation across primary and secondary healthcare settings. In the UK, all secondary care is provided within a hospital setting. Our aim was to generate stratified utilisation and cost data that could be suitable input parameters for future economic modelling. To do this, we set out to answer the question “What is the effect on the pattern and cost of healthcare utilisation of a referral to see a gastroenterologist among people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)?”.

IBS is a chronic, nonfatal condition, diagnosed in 11 % of the population [8]. Patients experience abdominal pain with diarrhoea or constipation, or both, but they have no structural bowel abnormality. International guidelines recommend diagnosis of IBS according to clinical criteria within primary care with minimal investigation, and also recommend IBS management within primary care [9–12]. Despite this, up to 20 % of patients are referred to see a gastroenterologist [13], and managing IBS constitutes between 25 and 50 % of gastroenterology outpatient workload [14–17]. Our study used linked electronic healthcare data from primary and secondary care in England to calculate rates and costs of healthcare utilisation for patients with IBS before and after their first appointment with a gastroenterologist.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Source

The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) is an anonymised longitudinal dataset of over 13 million medical records from over 640 primary care practices across the UK, collected prospectively from routine care since 1987 [4, 18]. It contains details of all primary care contact a person has had, the reason for the contact, who it was with and any medication prescribed. Records of almost two-thirds of English practices within the CPRD are linked to the NHS Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) [4, 5], which provide secondary care inpatient data from NHS hospitals in England since 1989 and outpatient data from 2004.

The cost to the health service of primary care utilisation is calculated nationally from unit costs, and is reported, along with social care costs, as NHS reference costs [6]. Costs of medication prescribed in primary care are contained in the British National Formulary (BNF). In England, the cost of secondary care to the health service (the payer) is calculated according to national tariff prices, based on the national average unit costs of providing each service (published as the National Schedule of Reference Costs [19]). The currency of patient activity used to attract a tariff is the Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) [7]. This is calculated according to an algorithm that clusters diagnostic codes, treatments and procedures with similar resource implications [7]. To generate the appropriate HRG code, secondary care events are grouped into spells, which include the different diagnoses made, the events that occurred during an admission, such as different specialists involved in care, procedures and investigations (not including blood tests), and the duration of care in different settings. The algorithm provides a hierarchy of the events coded within each spell, with adjustment for market factor forces and patient demographics, all of which are contained within the HES data. The National Casemix Office generates this algorithm and grouping software in order to attach the HRG data to the HES data [7]. The HRGs are currently updated annually in line with the tariff. Consequently, like the tariff, HRGs are year-specific. This study uses one cohort to compare costs before and after an intervention. To ensure changes in cost were from changes in utilisation and not changes within the HRG algorithm or tariff rates, the same HRG grouping algorithm was used for data in all years. We used 2012/2013 HRGs and tariff as they were the most recent and most consistent with the latest data we had available. For consistency, we used the 2012 unit and reference costs.

Where tariff costs do not exist, usually for rare conditions or treatments, reference costs are generated from the national average of the unit cost of care [19].

2.2 Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) Cohort

Construction of the initial cohort of patients with IBS has been fully described previously [20]. Briefly, individuals with records audited to acceptable research quality (where the record is checked for concordant dates, demographic data and consistent registration [18]) from CPRD practices with HES-linked data were identified as having IBS if they had a diagnostic (Read) code for IBS in either their CPRD clinical or referral file. The first event within the patient record explicitly coded as IBS defined the date of diagnosis. Patients were excluded if they had any diagnostic code for inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer or coeliac disease recorded within their entire health record. Patients have one unique HES identifier for all their secondary care records across the UK. If a patient moves between CPRD primary care practices they receive a new identifier and their records within the CPRD are not linked. Multiple CPRD records with one HES identifier were excluded (Fig. 1).

The first gastroenterology appointment was defined as a patient’s earliest recorded gastroenterology appointment within the HES outpatient data. The HES outpatient data are only available to link to CPRD records from 2004. Our datasets contained data until the end of 2012. To allow 3 full years of data for all healthcare domains before and after gastroenterology appointment, we selected those patients who had their first gastroenterology appointment in 2008 or 2009. Patients with fewer than 3 full years of data before or after the gastroenterology appointment were excluded.

2.3 Primary Care

Each primary care attendance was identified within the CPRD clinical file along with the professional with whom the consultation occurred. Appropriate reference costs were attached from the unit costs of health and social care [6]. Where consultation type was unknown (8.5 % of all consultations across the entire study period), a weighted average of the costs of the different consultation types available was used. This was calculated by summing the product of the proportion of each consultation type and its cost in each year.

2.4 Prescriptions

For each subject, we identified every separate prescription recorded in the CRPD prescriptions file. Drugs were classified according to their BNF chapter subparagraph, and the mean subparagraph cost was attached according to the 2012 England Prescription Cost Analysis (Health and Social Care Information Centre) [21]. Where missing data for the specific drug supplied prevented this (0.04 % of prescriptions), we attributed the 2012 median prescription cost as reported in the Prescription Cost Analysis (£38.74) [21].

2.5 Secondary Care

HES outpatient data were used to identify each attendance and specialty. Costs were taken from the NHS 2012 tariff for outpatient care. Costs in the tariff differ if appointments are first or subsequent visits, which are coded in HES so appropriate costs were attributed. Within HES, the treatment function code represents the specialised service within which a patient is treated [7, 22]. Events were linked to cost through the treatment function code within the HES outpatient data. All attendances were considered as single-consultant appointments for costing purposes, not multidisciplinary team appointments. Outpatient appointments excluded from Payment by Results (the tariff system that reimburses healthcare providers in the NHS [23]) in 2012, or occurring too infrequently at a national level, were not covered by the 2012 tariff. Costs for these appointments were taken from the unit price reported by appointment type in the 2012 reference costs [19].

Hospital admissions, including both day case and inpatient spells, but excluding colonoscopy, were extracted from HES data. Each separate hospital spell was identified for each patient along with the main treatment specialty. Spells with day-case codes, or inpatient stays of 1-day duration, were considered as day-case admissions. The HES inpatient data were reformatted so that the NHS 2012 grouper could be used to generate the appropriate HRG for each spell using the hierarchical algorithm [7]. These HRGs were linked to the 2012 NHS tariff costs. Elective or emergency prices were attached as appropriate and, if this status was unknown, elective prices were used. HRGs with no national tariff were identified and the appropriate price for each admission was attached from the 2012 reference costs [19]. The mean cost of day-case attendance in 2012 was £682, and £3215 per stay for inpatient admission; these costs were used when no reference costs were available.

2.6 Colonoscopy

Individual procedures can be specifically isolated and the cost attached. We identified colonoscopies in both the HES outpatient and hospital admissions data, and classified each procedure as elective or emergency according to coding in the dataset. The 2012 NHS tariff costs were attached.

2.7 Analysis

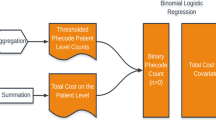

The duration of IBS before referral was defined as the time from the first IBS code in the patient record. Socioeconomic status within the CPRD dataset is on a patient postcode level [4] and is defined according to the quintile of the index of multiple deprivation. Smoking status was defined as ever or never smokers. The full clinical data available within the CPRD and HES record until 31 December 2012 were used to identify comorbidities, and from these the Charlson index was calculated [24]. For analysis, patients were classified as having no comorbidities (a score of 0) or comorbidities (a score of 1 or greater). Poisson regression analysis was used to generate adjusted rate ratios (RR), with robust standard errors used to produce 95 % confidence intervals (CI) for each of the domains of healthcare utilisation over the entire 6 years of data according to demographic strata. Three 1-year bands were defined for each patient before and after the date of the gastroenterology appointment, and the mean annual utilisation rates and costs were calculated. Rates of utilisation were approximately normally distributed and are presented in summary as mean and 95 % CI. Absolute differences in utilisation rate were calculated in each domain compared with the rate in the year 3 years before the gastroenterology appointment, and are presented with 95 % CIs. We hypothesised a priori that the use of healthcare might increase, leading to a referral to see a gastroenterologist for IBS, and fall afterwards. Consequently, we took 3 years before referral as the baseline year with which to compare utilisation rates. Absolute differences were reported as these were the most useful data for economic analyses. Mean individual annual costs by domain were calculated. The cost data best fit gamma distributions, therefore alpha and lambda parameters were calculated. The absolute cost difference and 95 % CI was calculated for total individual annual costs compared with the baseline year. Stratified overall annual mean costs and gamma distribution parameters were calculated according to sex, age at referral, duration of IBS, socioeconomic status, smoking status and comorbidity status. No costs were discounted. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) [25].

3 Results

Our original cohort identified 256,060 patient records that had been audited as acceptable for research from HES-linked CPRD practices, with IBS Read codes in either the clinical or referral file [20]. No HES outpatient data were available for 13 % of cases. Linking the HES data to the CPRD records identified 4562 patients (2 %) with multiple CPRD identities. Duplicated records or inconsistent dates were found in 12 % of the HES outpatient records, and these patient records were entirely excluded as it was not possible to establish which data were accurate. Of the IBS patients identified, 11 % had a gastroenterology outpatient appointment between 2004 and 2012. Of these, 4809 had a first gastroenterology outpatient appointment in 2008 or 2009. Three full years of CPRD and HES data before and after the gastroenterology appointment were available for 2076 of these patients (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the demographic data for this cohort. The median duration of IBS before a first gastroenterology outpatient appointment was 4.9 years (interquartile range [IQR] 0.2–12.4 years), 72 % (1520) were female, and the patients’ mean age at their gastroenterology appointment was 51.8 years (95 % CI 51.2–52.5 years).

3.1 Healthcare Utilisation

Increasing age and having IBS for longer than 2 years before referral to gastroenterology were both associated with increased primary care attendance, prescriptions and outpatient appointments (Table 2). Women utilised 26 % more primary care services, 21 % more outpatient services and had 35 % more prescriptions relative to men. There was no statistically significant difference in the rates of colonoscopies or inpatient admissions according to sex or age at referral. Rates of utilisation in all domains of healthcare, with the exception of colonoscopy, increased with improved deprivation. Rates of colonoscopy were almost double in nonsmokers, while rates of utilisation in all other healthcare domains were 7–40 % higher in smokers. The presence of comorbid conditions increased patients’ healthcare utilisation in all domains, with the exception of colonoscopy, by approximately 20 % (Table 2).

Over time, primary care utilisation, hospital inpatient, day-case admissions, outpatient appointments and colonoscopy rates all showed a similar pattern of utilisation, increasing before referral and peaking around the first gastroenterology appointment. The rates subsequently fell, but remained higher than pre-referral level (Table 3). Prescriptions have substantially higher rates in the years following referral compared with the years before referral. When considering the absolute difference, compared with 3 years before referral, there were 15 extra prescriptions per person per year (increased from 26 to 41) 3 years after referral. For every two patients, there were three extra primary care and three extra outpatient appointments.

3.2 Costs

Overall healthcare costs per patient increased by less than 25 % in the 3 years leading up to the first gastroenterology appointment (total mean individual cost increased by £772 (95 % CI £769–776) (Table 4). In the first year following, overall costs were £1393 higher than at baseline (95 % CI £1389–1396) and £625 higher than the year before gastroenterology appointment. After 3 years following referral, total costs per person remained one-third higher than they were 3 years before referral, i.e. £3567 compared with £2323, an increase of £1244 (95 % CI £1240–1248). Figure 2 shows the proportion of these costs each year that corresponded to each domain. Prescriptions accounted for over half of the total cost each year. Tables 5 and 6 show the stratified costs with gamma distribution parameters. The stratified data show similar patterns in costs as the RRs earlier described.

4 Discussion

This study demonstrates that the linked CPRD and HES data can be used to measure rates and change in healthcare utilisation with precise costs for patients. Using linked data of this type will potentially improve the validity of economic models considering complex healthcare interventions in real populations. Absolute difference in annual utilisation is important to measure for most economic evaluations. We have been able to use these data to calculate the difference in rates of inpatient, outpatient, and primary care and prescriptions before and after an intervention. Similarly, we have been able to attach the exact cost for each patient’s specific care use across the domains of healthcare for which the NHS is the payer. The data available within these datasets allowed the generation of stratified outcomes, useful for scenario analyses. We have reported costs with the appropriate distribution parameter values, suitable to input into economic modelling. Generating these parameters directly from the data without requiring any assumptions provides realistic parameters for probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

4.1 Previous Studies

The CPRD (known as the General Practice Research Database until 2012 [26]) and linked HES are well-established data sources for epidemiological and pharmacovigilance studies [27, 28]. Primary care data from the CPRD were first used as part of a cost-burden study 25 years ago [29], before reimbursement using HRGs was introduced (2003) and before HES-linked data were available (2008). In addition, before this linkage was available, but since costs have been calculated using HRGs, a series of studies comparing the comparative effectiveness and costs of various treatments for glaucoma were conducted [30–33]. These studies extracted utilisation data from the CPRD, but without HES linkage they used data within the CPRD referral file as evidence of secondary care attendance. This method has continued to be used following the linkage [34–39], but it misses events and the timing of events is less accurate than using HES data [40]. Our study was the first to use HES data to directly assess inpatient and outpatient secondary care use linked to the CPRD as the source of primary care use. Unit costs have been used in previous studies in place of calculating HRGs [30–36, 41]. The unit costs provide the national average cost of each type of care episode, whilst the HRG gives the specific cost generated by that patient for that event. Consequently, the HRGs provide a far more precise cost estimate, but patient-specific HRGs cannot be calculated in the absence of the HES data.

4.2 Strengths of These Linked Datasets

The large number of patient records contained within these datasets is a great strength. It allows both greater precision of utilisation and cost estimates and stratification by many variables with adequate power. Within this study, it has meant that we have been able to demand a number of eligibility criteria for cases without any substantial loss of heterogeneity (Table 1). This ability to stratify outcomes by a number of clinically relevant variables will reduce both structural and parameter assumptions when using these data within economic models. Not only this, but also our analysis, has shown that the heterogeneity of patients within the specific community where the intervention is implemented can be defined. This will be of increasing value given the current interest in stratified or personalised medicine and the need to find those people for whom interventions are most cost effective [42, 43].

When we downloaded the CPRD and HES-linked datasets for this study, we had data available in all healthcare domains for at least 8 years. These datasets now have at least 10 years of data for all domains and up to 30 years in primary care and prescriptions. This allows follow-up of patients for much greater durations than usually possible with randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Even though patients move between primary care practices, on registering with a CPRD-linked practice all their significant previous diagnoses are loaded into the CPRD record. The HES data are lifelong. The duration of these records is also therefore greater than in insurance datasets. Alongside this, although not accessed for this study, death registry data are linked to CPRD records. The duration of follow-up reduces the need for extensive assumptions and predictions regarding long-term outcomes, which can reduce transparency and increase uncertainty and bias [44, 45].

The data within these datasets are generated through routine care. They reflect actual clinical practice rather than the closely controlled setting of RCTs. RCTs can be highly selected, with outcomes that are not replicated in general clinical practice [46]. For economic evaluation, this means that predictions and expectations based on such data are not realised [47]. The real-world nature of the data in the CPRD and HES means the outcomes are readily generalisable. These databases are also more generalisable to the whole population than results of similar studies from insurance claims data. The NHS provides universal healthcare, unlike insurance companies. Datasets from these organisations are limited to people eligible for public insurance or individuals insured by one provider, and the terms of their insurance cover, for instance which facilities they can access and when, may cause patients to change their healthcare utilisation behaviour.

CPRD and HES data are relatively easily available on application to the administrators; the cost data are all publicly available. The nature of these data and the potential to directly link costs to them make studies relatively cheap and quick to replicate. Thus, policy outcomes can be efficiently analysed as well as the predictions of cost-effectiveness analyses in the postmarketing of drugs and devices.

4.3 Weaknesses of These Linked Datasets

One of the greatest weaknesses of using routinely collected data is missing data. The CPRD is audited on a regular basis to ensure that the data recorded are complete and accurate [4, 18]. Despite this, in fewer than 5 % of records event dates are not recorded or diagnostic codes are missing. This was higher in the HES outpatient data (12 %). The missingness of these data is likely to be random. Consequently, in this study we had sufficient data to exclude those records. Other data are not recorded at all. One example from this study was disease severity. For other conditions, diagnostic codes or other recorded information such as investigation results indicate disease severity, but for IBS there are no such data. Similarly, within these datasets no data record symptom improvement or quality-of-life information. This means that for diseases such as IBS with no attributable mortality or pathophysiological measurement, deterioration or improvement is unknown. This makes deriving disease-state transition probabilities very difficult in conditions such as IBS. In other conditions with clearly demarcated disease states, the proportion of a cohort in each state over time would be easier to define.

A limitation of any electronic database study within healthcare is the difficulty in verifying coding accuracy. CPRD data are regularly audited to ensure their quality [18]. Many studies have assessed the internal validity of CPRD coding, using either algorithms or sensitivity analyses, and the external validity by directly reviewing patient records or sending general practitioners questionnaires [48, 49]. Over a range of 183 diagnoses, the median proportion of cases confirmed was 89 % [48]. Coding for IBS specifically has been validated via questionnaires to general practitioners, who confirmed IBS diagnosis in 99 % of patients with a first IBS code whilst enrolled at that practice, and 84 % of patients with an IBS code from a previous practice [50]. Individual coding errors are likely to be independent of any intervention or population analysed, and independent of cost. Consequently, it is unlikely that differential misclassification from inaccurate coding occurs at an individual level. However, it is likely that changes in external factors that link recorded outcomes to reimbursement change the accuracy and frequency of coding, which could introduce bias [51, 52].

Within these datasets, the duration of patient enrolment varies. We had sufficient cases to restrict our analysis to only those patients with 3 full years of data either side of the first gastroenterology appointment. Limiting our population could introduce selection bias towards relatively well patients and those less likely to move, such as older patients. This would not be an appropriate approach if the condition under investigation had associated mortality impact, but IBS does not. Comparing all eligible patients with gastroenterology appointments in 2008 or 2009 with those who had data available for the full 6 years (Table 1), the demographics remain broadly similar. There is evidence of proportionally fewer patients aged under 30 years being eligible but this has little effect on the mean age of the sample. In situations where survival (or mortality) was important, or selecting only patients with complete years of data would cause substantial selection bias, inverse probability weighting of costs would be an appropriate method for analysis [53].

The nature of the CPRD and HES datasets mean that the utilisation data and associated costs are from the payer’s perspective only. In the current climate, this is adequate for Health Technology Assessments. If conducting an analysis of societal impact, then additional data from other sources would be required. Likewise, these data are UK-specific, which might limit generalisability outside the NHS. For similarly organised healthcare systems, it is feasible to attach other system-specific costing structures to the utilisation data but this would need further analysis.

A gastroenterology appointment for IBS diagnosis or management is not currently recommended as best practice [9, 12] therefore referral from primary care is not standardised. Consequently, the patients who see a gastroenterologist are likely to be systematically different to those who do not. It is for this reason that we used a before and after study design. However, these data cannot establish the counterfactual utilisation and cost trajectories in the absence of a gastroenterology appointment. For instance, it is possible that utilisation and costs increase in these patients if they do not visit a gastroenterologist. Comparing these patients with IBS to those never referred would lead to confounding by indication. This is a limitation of the data in these databases compared with RCT data. Propensity score matching has gained popularity for assessing the probability of intervention allocation according to baseline covariates [54]. This method relies on known and measured variables, at least partially explaining differences between those referred and not referred. Table 1 shows that the demographic variables we measured were similar between the referred and nonreferred patients, which makes propensity score matching less useful here. It has previously been found that the factors most likely to predict referral to a gastroenterologist are reporting stress worsening symptoms and having more than three bowel movements per day, which are not variables recorded within the CPRD and HES dataset [13]. Alternatively, epoch analysis aims to estimate causal effect when patients switch interventions during longitudinal observational studies [55]. However, in our study, referral to gastroenterology is a once-only intervention. Patients who are ‘never referred’ can become ‘referred’, but not vice versa. Thus, to use these datasets to assess the potential cost effectiveness of referring patients with IBS to gastroenterology, assumptions regarding utilisation and costs in the absence of a gastroenterology referral should be included in a scenario analysis. As these datasets develop, their strengths in size and in reflecting actual clinical practice can be maintained by conducting a randomised trial prospectively through the CPRD general practices [56]. For instance, it is now possible to alert CPRD-linked general practitioners through their electronic records system when they consult patients potentially eligible for a trial [56, 57].

The lack of linked quality-of-life data within these datasets means that linking the utilisation and cost outcomes with other sources of quality-of-life data for a cost-effectiveness study will be challenging. However, we acknowledge that this would be less difficult in conditions with well-defined disease progression indicators recorded within routine healthcare data. We have demonstrated the greatest strength in these data is the capacity to define patient-level demographic factors, comorbidities and risk factors, and link them with specific costs. The potential for these data is substantial. Individual-level simulations using these data could directly sample individuals, avoiding the need to generate hypothetical ‘patients’ from parameter distributions [58], and might provide better adjustment for unknown confounders [59, 60]. There is also great interest in the potential of real-world electronic health data for validating economic model predictions [61]. The large numbers of records available with data that allow characterisation of patient heterogeneity will become more useful with increasing stratification of patient’s treatment according to risk factors or predictors of response.

5 Conclusions

These linked datasets provide useful data for large numbers of patients, which allows stratification of costs and new insights into healthcare utilisation. It is possible to derive relevant parameters and distributions directly from the population of interest. We advise caution when choosing to use these datasets, depending on the disease investigated, if the aim is to use the outcomes generated in cost-effectiveness analysis. The important disease states, or markers of them, should be events routinely recorded in healthcare data so states can be adequately characterised and linked to quality-of-life data from other sources.

References

Caro JJ. Psst, have I got a model for you. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(2):139–41.

Masters E, Zlateva G, Harris N. Real world data for use in the real world: the pain paradigm. ISPOR Connect 2013;19:9–11. Available at: http://www.ispor.org/news/articles/march-april13/real-world-data.asp.

Asaria M, Walker S, Sculpher MJ, et al. Challenges of conducting economic evaluations using linked electronic health records—CPRD and HES in the United Kingdom. Value Health. 2013;16:A580.

Clinical Practice Research Datalink. CPRD Gold Flat files release notes. London.

Puri S. Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data and GOLD documentation.

Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care 2011. Canterbury: University of Kent; 2011.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Introduction to healthcare resource groups. Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/hrg. Accessed 22 Sep 2014.

Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:71–80.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care. NICE Clinical Guideline, No. 61. London: NICE; 2008.

Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, et al. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45(Suppl 2):II43–7.

Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–91.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care. NICE Clinical Guideline, No. 61. Manchester: NICE; 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg61. Accessed 29 Jun 2015.

Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut. 2000;46:78–82.

Lacy BE, Rosemore J, Robertson D, et al. Physicians’ attitudes and practices in the evaluation and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:892–902.

Wells NE, Hahn BA, Whorwell PJ. Clinical economics review: irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:1019–30.

Smith GD, Steinke DT, Kinnear M, et al. A comparison of irritable bowel syndrome patients managed in primary and secondary care: the Episode IBS study. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:503–7.

Ford AC, Bercik P, Morgan DG, et al. Characteristics of functional bowel disorder patients: a cross-sectional survey using the Rome III criteria. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:312–21.

Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Available at: http://www.cprd.com/home/. Accessed 23 May 2013.

Department of Health. NHS reference costs: financial year 2011 to 2012. London: Department of Health; 2012.

Canavan C, Card T, West J. The incidence of other gastroenterological disease following diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome in the UK: a cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106478.

Health and Social Care Information Centre. Prescription cost analysis—England, 2012 [NS]. 4 Apr 2013. Available at: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB10610.

Record C, Day C. Britain’s alcohol market: how minimum alcohol prices could stop moderate drinkers subsidising those drinking at hazardous and harmful levels. Clin Med. 2009;9:421–5.

Department of Health Payment by Results Team. A simple guide to payment by results. NHS, Department of Health; 2012. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213150/PbR-Simple-Guide-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 1 Sept 2015.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676–82.

Stata statistical software. College Station (TX): StataCorp LP.

Clinical Practice Research Datalink. From GPRD to CPRD. Frequently asked questions. 2013. Available at: https://www.rct.cprd.com/elung/faqs/elung-49/from-gprd-to-cprd-49/. Accessed 25 Jan 2015.

Williams T, van Staa T, Puri S, et al. Recent advances in the utility and use of the General Practice Research Database as an example of a UK Primary Care Data resource. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2012;3:89–99.

Chen Y-C, Wu J-C, Haschler I, et al. Academic impact of a public electronic health database: bibliometric analysis of studies using the general practice research database. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21404.

Dolan P, Torgerson DJ. The cost of treating osteoporotic fractures in the United Kingdom female population. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:611–7.

Denis P, Lafuma A, Berdeaux G. Costs and persistence of alpha-2 adrenergic agonists versus carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, both associated with prostaglandin analogues, for glaucoma as recorded by The United Kingdom General Practitioner Research Database. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2:321–9.

Lafuma A, Laurendeau C, Berdeaux G. Costs and persistence of brimonidine versus brinzolamide in everyday glaucoma care: an analysis conducted on the UK General Practitioner Research Database. J Med Econ. 2008;11:485–97.

Deschaseaux-Voinet C, Lafuma A, Berdeaux G. Cost and effectiveness of brinzolamide versus dorzolamide in current practice: an analysis based on the UK-GPRD database. J Med Econ. 2003;6(1–4):69–78.

Lafuma A, Berdeaux G. Costs and effectiveness of travoprost versus a dorzolamide + timolol fixed combination in first-line treatment of glaucoma: analysis conducted on the United Kingdom General Practitioner Research Database. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:3009–16.

Gulliford MC, Charlton J, Bhattarai N, et al. Impact and cost-effectiveness of a universal strategy to promote physical activity in primary care: population-based cohort study and Markov model. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15:341–51.

Hong J, Reed C, Novick D, et al. Costs associated with treatment of chronic low back pain: an analysis of the UK General Practice Research Database. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38:75–82.

Reed C, Novick D, Lenox-smith A, et al. Health care costs before and after diagnosis of depression in patients with unexplained pain : a retrospective cohort study using the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:37–47.

Shi N, Cao Z, Durden E, et al. Healthcare utilization among patients with depression before and after initiating duloxetine in the United Kingdom. J Med Econ. 2012;15:672–80.

Boggon R, Lip GYH, Gallagher AM, et al. Resource utilization and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: a case control study. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2012;10:249–59.

Violato M, Gray A, Papanicolas I, et al. Resource use and costs associated with coeliac disease before and after diagnosis in 3,646 cases: results of a UK primary care database analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41308.

Abdul Sultan A, Tata LJ, Grainge MJ, et al. The incidence of first venous thromboembolism in and around pregnancy using linked primary and secondary care data: a population based cohort study from England and comparative meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70310.

Brilleman SL, Purdy S, Salisbury C, et al. Implications of comorbidity for primary care costs in the UK: a retrospective observational study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e274–82.

Basu A. Economics of individualization in comparative effectiveness research and a basis for a patient-centered health care. J Health Econ. 2011;30:549–59.

Groot Koerkamp B, Weinstein MC, Stijnen T, et al. Uncertainty and patient heterogeneity in medical decision models. Med Decis Making. 2010;30:194–205.

Philips Z, Bojke L, Sculpher M, et al. Good practice guidelines for decision-analytic modelling in health technology assessment. Pharmacoeconomics. 2006;24:355–71.

Caro JJ, Briggs AH, Siebert U. Modeling good research practices—overview: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-1. Value Health. 2012;15(6):796–803.

Bijkerk CJ, Muris JWM, Knottnerus JA, et al. Randomized patients in IBS research had different disease characteristics compared to eligible and recruited patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:1176–81.

Van Staa T-P, Leufkens HG, Zhang B, et al. A comparison of cost effectiveness using data from randomized trials or actual clinical practice: selective COX-2 inhibitors as an example. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000194.

Herrett E, Thomas SL, Schoonen WM, et al. Validation and validity of diagnoses in the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:4–14.

Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database : a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(572):e128–36.

Ruigómez A, García Rodríguez LA, Johansson S, et al. Is hormone replacement therapy associated with an increased risk of irritable bowel syndrome? Maturitas. 2003;44:133–40.

Carey IM, Dewilde S, Harris T, et al. Spurious trends in coronary heart disease incidence: unintended consequences of the new GP contract? Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:486–9.

Carey IM, Nightingale CM, DeWilde S, et al. Blood pressure recording bias during a period when the Quality and Outcomes Framework was introduced. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:764–70.

Griffiths RI, Gleeson ML, Danese MD, et al. Inverse probability weighted least squares regression in the analysis of time-censored cost data: an evaluation of the approach using SEER-Medicare. Value Health. 2012;15:656–63.

Manca A, Austin P. Using propensity score methods to analyse individual patient-level cost-effectiveness data from observational studies. The University of York Health Econometrics and Data Group (HEDG) Working Paper 08/20; July 2008. Available at: http://www.york.ac.uk/media/economics/documents/herc/wp/08_20.pdf.

Windmeijer F, Kontodimas S, Knapp M, et al. Methodological approach for assessing the cost-effectiveness of treatments using longitudinal observational data: the SOHO study. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2006;22:460–8.

Van Staa T-P, Dyson L, McCann G, et al. The opportunities and challenges of pragmatic point-of-care randomised trials using routinely collected electronic records: evaluations of two exemplar trials. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18:1–146.

Van Staa T-P, Klungel O, Smeeth L. Use of electronic healthcare records in large-scale simple randomized trials at the point of care for the documentation of value-based medicine. J Intern Med. 2014;275:562–9.

Brennan A, Chick SE, Davies R. A taxonomy of model structures for economic evaluation of health technologies. Health Econ. 2006;15(12):1295–310.

Kopec JA, Sayre EC, Flanagan WM, et al. Development of a population-based microsimulation model of osteoarthritis in Canada. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(3):303–11.

Briggs AH, Weinstein MC, Fenwick EAL, et al. Model parameter estimation and uncertainty: a report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-6. Value Health. 2012;15:835–42.

King F, Willford J, Nelson M. The power of real world evidence: filling the gap between basic research and decision making. Access Point. 2013;4:16–21.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

All authors have completed competing interest forms, and declare that Caroline Canavan received support from the Medical Research Council for the submitted work; Caroline Canavan, Joe West and Timothy Card have no relationships with any companies that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, or any nonfinancial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

The work of the researchers is independent from the funders, who had no input into any part of the study. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in this study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Caroline Canavan, Timothy Card and Joe West designed the study; Joe West and Caroline Canavan requested the data; Caroline Canavan performed the initial analyses, which was reviewed by Joe West and Timothy Card; results were interpreted by Caroline Canavan, Joe West and Timothy Card; and Caroline Canavan, Joe West and Timothy Card wrote and revised the manuscript.

The CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee provided ethical approval for this project (protocol approval reference 12_047R).

Data sharing

Data are available on request from the CPRD. Their provision requires the purchase of a license, and our license does not permit us to make them publicly available to all. We used data from the version collected in July 2012 and have clearly specified the data selected in our Methods section. To allow identical data to be obtained by others, via the purchase of a license, we will provide the code lists on request. Licences are available from the CPRD (http://www.cprd.com): The Clinical Practice Research Datalink Group, The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, 5th Floor, 151 Buckingham Palace Road, Victoria, London SW1 W 9SZ.

Caroline Canavan affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; no aspects of the study have been omitted and any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Canavan, C., West, J. & Card, T. Calculating Total Health Service Utilisation and Costs from Routinely Collected Electronic Health Records Using the Example of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome Before and After Their First Gastroenterology Appointment. PharmacoEconomics 34, 181–194 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0339-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0339-y