Abstract

Background

The Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI), launched in 2007 by the State Council, aims to cover around 420 million urban residents in China.

Objective

This study aimed to assess the impact of URBMI on health services access (especially inpatient utilisation) in urban China.

Methods

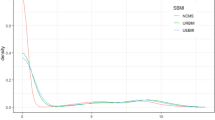

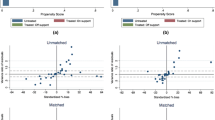

Data was drawn from the recent four-wave URBMI Survey (2008–2011). Probit and recursive bivariate probit models have been adopted to handle the possible endogeneity of medical insurance in the utilisation equations.

Results

Based on the preferred results from the unbalanced four-wave panel data, we found that the URBMI had significantly increased the likelihood of receiving inpatient treatment in the past year. However, the insurance effect on reducing the refused hospitalisation was insignificant. Finally, the URBMI had also increased the probability of using outpatient services in the past 2 weeks, although the insurance reimburses mainly against critical outpatient care.

Conclusions

Given that it is still early days for the URBMI scheme, the positive effect on health services utilisation is appreciable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Five (seven) out of nine sample cities of the URBMI Survey reimburse regular (critical) outpatient services. In addition, three out of nine sample cities reimburse outpatient services due to accidents for young people [4]. In sum, the URBMI scheme covers at least part of outpatient health services in all nine sample cities reviewed.

The simultaneous equation model is more efficient than the two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimator since the potential errors correlation is not taken into account in the 2SLS [18].

As noted at Dardanoni and Li Donni [23], owing to the presence of multidimensional private information, this analysing framework could estimate the incentive effect of medical insurance accurately; however, it may be difficult to clearly understand the selection effect.

We thank an anonymous referee who pointed to this explanation.

It would be ideal to let u i freely correlated with independent variables; however, for the non-linear models, the strategies that are widely adopted in the linear regression model to eliminate individual heterogeneity could not be directly applied when an independent variable is a binary response. The conditional fixed-effects logit estimator using conditional maximum likelihood estimator is one solution to eliminate the u i ; however, in that case, only the observations that change the dependent variable status would be used [24]. As a robust analysis, we have also adopted the fixed-effects logit estimator to estimate the utilisation equations and compared results with random-effects probit estimates.

Nine cities which are included in the URBMI Survey are located across Western China (Baotou City, Chengdu City, Xining City, Urumqi City), Central China (Changde City, Jilin City, Shaoxing City), and Eastern China (Xiamen City, Zibo City).

Seven indicators were adopted in the cluster analysis, including GDP per capita, population size, population density, average number of hospital beds, average number of physicians, average financing cost of URBMI, and average financing cost of UEBMI social pooling account in 2006 [4].

One potential worry of using self-reported income is that respondents are likely to under-report their true income. An alternative strategy is to use household expenditure to proxy the wealth. To avoid the endogenous issue, we calculated the net household expenditure in the past year, which is defined as total household expenditure minus health expenditure [31]. We tested for both of the above two variables and it transpires that the results are comparable, with only slight differences in the magnitudes. Considering that more missing values exist in expenditure variables, the results reported here only come from the self-reported income information.

It would be ideal to further include supply-side factors into the independent variables; we did not include those variables because within each city, the city-level office defines the single plan (eligibility criterion, financing and benefit package) for the URBMI candidate throughout the city. So each eligible consumer can only choose whether or not to purchase the insurance but not how much to pay. The supply-side effects are captured by the city dummies.

There could be some worry about multicollinearity between household head’s drinking behaviour and household members’ drinking behaviour. We calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) after the probit estimate on the URBMI demand equation using the pooled four-wave data. The mean VIF was 2.24 and the highest VIF value (7.9) was found for the household size variable. In one case [Table 4, Column (8)], the household size was excluded from the regression to help ensure concavity of the log-likelihood.

References

Liu GG. Beijing’s perspective: the internal debate on health care reform. In: Freeman C, Lu X, editors. China’s capacity to manage infectious diseases. Washington, DC: CSIS; 2009. p. 51–8.

Ministry of Health of China. China’s health statistical yearbook 2011. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College Press; 2011.

Chen G, Inder B, Lorgelly P, Hollingsworth B. The cyclical behaviour of public and private health expenditure in China. Health Econ. 2013;22(9):1071–92.

Lin W, Liu GG, Chen G. The Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance: a landmark reform towards universal coverage in China. Health Econ. 2009;18(S2):83–96.

Guo Y, Shibuya K, Cheng G, et al. Tracking China’s health reform. Lancet. 2010;375(9720):1056–8.

Meng Q, Xu L, Zhang Y, et al. Trends in access to health services and financial protection in China between 2003 and 2011: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):805–14.

Liang L, Langenbrunner JC. The long march to universal coverage: lessons from China. UNICO Studies Series No. 9. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2013.

World Bank. Main report. The path to integrated insurance system in China, vol. 2. China Health Policy Notes No. 3. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2010.

Dong K. Medical insurance system evolution in China. China Econ Rev. 2009;20(4):591–7.

Newhouse JP. Free for all? Lessons from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996.

Buchmueller TC, Grumbach K, Kronick R, Kahn JG. The effect of health insurance on medical care utilization and implications for insurance expansion: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62:3–30.

Freeman JD, Kadiyala S, Bell JF, et al. The causal effect of health insurance on utilization and outcomes in adults: a systematic review of US studies. Med Care. 2008;46(10):1023–32.

Zhong H. Effect of patient reimbursement method on health-care utilization: evidence from China. Health Econ. 2011;20(11):1312–29.

Li X, Zhang W. The impacts of health insurance on health care utilization among the older people in China. Soc Sci Med. 2013;85:59–65.

Cutler DM, Finkelstein A, McGarry K. Preference heterogeneity and insurance markets: explaining a puzzle of insurance. Am Econ Rev. 2008;98(2):157–62.

Cohen A, Siegelman P. Testing for adverse selection in insurance markets. J Risk Insur. 2010;77(1):39–84.

Finkelstein A, McGarry K. Multiple dimensions of private information: evidence from the long-term care insurance market. Am Econ Rev. 2006;96(4):938–58.

Cai L, Kalb G. Health status and labour force participation: evidence from Australia. Health Econ. 2006;15(3):241–61.

Holly A, Gardiol L, Domenighetti G, et al. An econometric model of health care utilization and health insurance in Switzerland. Eur Econ Rev. 1998;42(3–5):513–22.

Shen Y, Hendricks A, Wang F, et al. The impact of private insurance coverage on veterans’ use of VA care: insurance and selection effects. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(1):267–86.

Cheng TC, Vahid F. Demand for hospital care and private health insurance in a mixed public-private system: empirical evidence using a simultaneous equation modeling approach. Health, Econometrics and Data Group (HEDG) Working Papers 10/25. Heslington: Department of Economics, University of York; 2010.

Hopkins S, Kidd MP, Ulker A. Private health insurance status and utilisation of dental services in Australia. Econ Rec. 2013;89(285):194–206.

Dardanoni V, Li Donni P. Incentive and selection effects of Medigap insurance on inpatient care. J Health Econ. 2012;31(3):457–70.

Greene WH. Econometric analysis. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 2002.

Wilde J. Identification of multiple equation probit models with endogenous dummy regressors. Econ Lett. 2000;69(3):309–12.

Jones A. Applied econometrics for health economists: a practical guide. 2nd ed. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2007.

Roodman D. Estimating fully observed recursive mixed-process models with cmp. Working Papers 168. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development; 2009.

Bennett S, Woods T, Liyanage WM, et al. A simplified general method for cluster-sample surveys of health in developing countries. World Health Stat Q. 1991;44(3):98–106.

Savage E, Wright DJ. Moral hazard and adverse selection in Australian private hospitals: 1989–1990. J Health Econ. 2003;22(3):331–59.

Doiron D, Jones G, Savage E. Healthy, wealthy and insured? The role of self-assessed health in the demand for private health insurance. Health Econ. 2008;17(3):317–24.

Zhang L, Wang H. Dynamic process of adverse selection: evidence from a subsidized community-based health insurance in rural China. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(7):1173–82.

Chen G, Yan X. Demand for voluntary basic medical insurance in urban China: panel evidence from the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance scheme. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(8):658–68.

De Meza D, Webb DC. Advantageous selection in insurance markets. RAND J Econ. 2001;32(2):249–62.

Fang H, Keane MP, Silverman D. Sources of advantageous selection: evidence from the Medigap insurance market. J Polit Econ. 2008;116(2):303–50.

Wagstaff A, Lindelow M, Gao J, et al. Extending health insurance to the rural population: an impact evaluation of China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme. J Health Econ. 2009;28(9):1–19.

Zhou Z, Gao J, Xue Q, et al. Effects of Rural Mutual Health Care on outpatient service utilization in Chinese village medical institutions: evidence from panel data. Health Econ. 2009;18(Suppl 2):S129–36.

Zhou Z, Su Y, Gao J, et al. New estimates of elasticity of demand for healthcare in rural China. Health Policy. 2011;103(2):255–65.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Peking University China Center for Health Economics Research for providing the survey data. We are grateful to two anonymous referees for their detailed and helpful suggestions. We would also like to thank Paula Lorgelly from Monash University for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper. Responsibility for any remaining errors lies solely with the authors.

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

Gang Chen conceptualised the research, carried out the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and revised the manuscript. Gordon G. Liu supervised the URBMI Survey, conceptualised the research, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Fei Xu contributed to the data analysis, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. Gang Chen acts as the overall guarantor of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, G., Liu, G.G. & Xu, F. The Impact of the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance on Health Services Utilisation in China. PharmacoEconomics 32, 277–292 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-013-0097-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-013-0097-7