Abstract

The aim of this study is to estimate the causal effect of family size on the proximity between older mothers and adult children by using a large administrative data set from Sweden. Our main results show that adult children in Sweden are not constrained by sibship size in choosing where to live: for families with more than one child, sibship size does not affect child-mother proximity. For aging parents, however, having fewer children reduces the probability of having at least one child living nearby, which is likely to have consequences for the intensity of intergenerational contact and eldercare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the fifth and sixth sections, we discuss the methodology and the interpretation of the estimated effects in more detail.

Evidence from the United States suggests that older parents indeed expect to move closer to adult children out of need (Silverstein and Angelelli 1998). In what follows, we provide descriptive evidence showing that the distance between adult children and their parents remains relatively stable over time, suggesting that intergenerational geographic convergence is not a common phenomenon in Sweden.

Parishes constitute the smallest administrative unit that is used in Sweden for population censuses. Municipalities are larger service-providing local authorities, of which there were 289 in 1990.

A detailed description of how the 2003 education register has been translated into years of education can be found in the working paper version of this article (Holmlund et al. 2009).

Throughout the article, we interpret the coefficients in the log-linear models in percentage terms, obtaining the percentage changes using the formula (exp(beta) – 1).

The geographic distance between children and mothers might also vary by children’s marital status (Compton and Pollak 2009). Unfortunately, we do not have information on adult children’s marital status in our data set and therefore cannot investigate this issue.

The regressions here are run at the level of the mother; that is, we have one observation per family.

As mentioned in the fourth section, we controlled for adult children’s education in our IV regressions because recent research suggests that individuals with higher levels of education are geographically more mobile. However, a critic might argue that adult children’s education is likely to be correlated with the error term in Eq. (2), leading to biased estimates of family size on child-parent geographic proximity. In unreported regressions, we therefore estimated the regressions without controlling for adult children’s education, which did not alter our overall conclusions. The results are available from the authors upon request. As we will discuss further in the next section, it is important to keep in mind that these results hold for families with two or more children, and not necessarily for the shift from being an only child to having siblings. Finally, in unreported regressions, we also estimated the preceding regressions separately for women and men. The results did not point to considerable differences in the effect of family size on child-parent geographic distances by gender.

Bedard and Deschênes (2004) used the sex of the first child as an exogenous variation for family breakup in order to investigate the causal effect of marital dissolution on the mother’s economic status. However, in our context, the sex of the first child is unlikely to be a valid instrument for family size because gender might have a direct effect on adult children’s location decisions.

References

Angrist, J. D., & Evans, W. N. (1998). Children and their parents’ labor supply: Evidence from exogenous variation in family size. American Economic Review, 88, 450–477.

Angrist, J. D., Lavy, V., & Schlosser, A. (2010). Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Labor Economics, 28, 773–823.

Aslund, O., & Grönqvist, H. (2010). Family size and child outcomes: Is there really no trade-off? Labour Economics, 17, 130–139.

Bedard, K., & Deschênes, O. (2004). Sex preferences, marital dissolution, and the economic status of women. Journal of Human Resources, 40, 411–434.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2005). The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 669–700.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2010). Small family, smart family? Family size and the IQ scores of young men. Journal of Human Resources, 45, 33–58.

Cheadle, J. E., Amato, P. R., & King, V. (2010). Patterns of nonresident father contact. Demography, 47, 205–225.

Compton, J., & Pollak, R. A. (2009). Proximity and coresidence of adult children and their parents: Description and correlates (Working Paper 2009–215). Ann Arbor: Michigan Retirement Research Center, University of Michigan.

Couch, K. A., Douglas, M. C., & Wolf, D. A. (1999). Time? Money? Both? The allocation of resources to older parents. Demography, 36, 219–232.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2012). The intergenerational transmission of risk and trust attitudes. Review of Economic Studies, 79, 645–677.

Ermisch, J. (2009). Adult-child parent relationships. In M. Brynin & J. Ermisch (Eds.), Changing relationships (pp. 111–126). New York: Routledge.

Greenwell, L., & Bengston, V. L. (1997). Geographic distance and contact between middle-aged children and their parents: The effects of social class over 20 years. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 52B, S13–S26.

Hank, K. (2007). Proximity and contacts between older parents and their children: A European comparison. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 157–173.

Holmlund, H., Rainer, H., & Siedler, T. (2009). Meet the parents? The causal effect of family size on the geographic distance between adult children and older parents (IZA Discussion Paper No. 4398). Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor.

Jaeger, D. A., Bonin, H., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2010). Direct evidence on risk attitudes and migration. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92, 684–689.

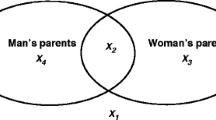

Konrad, K. A., Künemund, H., Lommerud, K. E., & Robledo, J. R. (2002). Geography of the family. American Economic Review, 92, 981–998.

Løken, K. V., Lommerud, K. E., & Lundberg, S. (2012). Your place or mine? On the residence choice of young couples in Norway. Advance online publication. Demography. doi:10.1007/s13524-012-0142-8

Machin, S., Pelkonen, P., & Salvanes, K. G. (2012). Education and mobility. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10, 417–450.

Malmberg, G., & Pettersson, A. (2007). Distance to elderly parents: Analyses of Swedish register data. Demographic Research, 17(23), 679–704. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2007.17.23

Marini, M. M. (1985). Determinants of the timing of adult role entry. Social Science Research, 14, 309–350.

Michielin, F., & Mulder, C. H. (2007). Geographical distances between adult children and their parents in the Netherlands. Demographic Research, 17(22), 655–678. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2007.17.22

Moffitt, R. (2005). Remarks on the analysis of causal relationships in population research. Demography, 41, 91–108.

Pettersson, A., & Malmberg, G. (2009). Adult children and elderly parents as mobility attractions in Sweden. Population, Space and Place, 15, 343–357.

Pezzin, L. E., Pollak, R. A., & Schone, B. S. (2006). Efficiency in family bargaining: Living arrangements and caregiving decisions of adult children and disabled elderly parents. CESifo Economic Studies, 53, 69–96.

Rainer, H., & Siedler, T. (2009). O brother, where art thou? The effects of having a sibling on geographic mobility and labor market outcomes. Economica, 76, 528–556.

Rainer, H., & Siedler, T. (2012). Family location and caregiving patterns from an international perspective. Population and Development Review, 38, 337–351.

Rosenzweig, M. R., & Wolpin, K. I. (1980). Testing the quantity-quality fertility model: The use of twins as a natural experiment. Econometrica, 48, 227–240.

Schoeni, R. F., & Ofstedal, M. B. (2010). Key themes in research on the demography of aging. Demography, 47, S5–S15.

Shea, D., Davey, A., Femia, E. E., Zarit, S. H., Sundström, G., Berg, S., & Smyer, M. A. (2003). Exploring assistance in Sweden and the United States. The Gerontologist, 43, 712–721.

Shelton, N., & Grundy, E. (2000). Proximity of adult children to their parents in Great Britain. International Journal of Population Geography, 6, 181–195.

Silverstein, M. (1995). Stability and change in temporal distance between the elderly and their children. Demography, 32, 29–45.

Silverstein, M., & Angelelli, J. J. (1998). Older parents’ expectations of moving closer to their children. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 53B, S153–S163.

Staiger, D., & Stock, J. (1997). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica, 65, 557–586.

Treas, J. (1979). Intergenerational families and social changes. In P. Ragan (Ed.), Aging parents (pp. 58–65). Los Angeles: Andrus Gerontology Center, University of Southern California.

United Nations. (2005). United Nations expert group meeting on social and economic implications of changing population age structures. Mexico City, Mexico: Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Division.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Economic and Social Research Council under Grant RES-000-22-2684 and through the Research Centre on Micro-Social Change (MiSoC) (Award No. RES-518-28-001). Helena Holmlund would also like to thank the Jan Wallander and Tom Hedelius Foundation for financial support. We also thank seminar participants at the 2007 IZA Workshop on Long-Term Care, the 2009 ESPE conference, and seminar participants at the University St. Gallen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Holmlund, H., Rainer, H. & Siedler, T. Meet the Parents? Family Size and the Geographic Proximity Between Adult Children and Older Mothers in Sweden. Demography 50, 903–931 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0181-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0181-1