Abstract

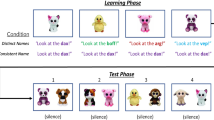

We use mental files to present an analysis of children's developing understanding of identity in alternative naming tasks and belief. The core assumption is that younger children below the age of about 4 years create different files for an object depending on how the object is individuated (e.g., as a rabbit or as an animal). They can anchor them to the same object, hence think of the same object whether they think of it as a rabbit or as an animal. However, the claim is, they cannot yet link their files to one another to represent that they have the same referent. Without linking the information contained in one file is not available in the other file. Hence, when thinking of the object as a rabbit (using the rabbit file) the information that it is also an animal is not available. For representing a person's belief about an object a vicarious file contains what the person believes about the object. To capture that the belief is about that object the vicarious file has to be linked to the regular file, which by assumption children younger than 4 years cannot do. This assumption can therefore explain why problems with alternative naming and understanding false beliefs are overcome at the same age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Or as one of the reviewers has pointed out that the repeated emphasis on not repeating what the experimenter has said may lead to a pink elephant phenomenon that the children trying to avoid repetition can’t help say what they are intent on avoiding.

One may well wonder what children, who despite the very explicit instructions not to repeat partner’s answer still repeat that very label, do understand of the instructions. We don’t really know. They probably try to be cooperative and make the best of something they don’t fully comprehend. They most likely pick up on “having to say what the ostended object is,” and then cannot but repeat what the experimenter had just called it. Interestingly, when instructed to pretend the object was something else and, therefore, call the object something it is not (control condition in Experiment 4 of Doherty and Perner 1998) children had few problems.

Markman (1989) expressed this view in the context of explaining mutual exclusivity phenomena: “children may believe that an object has one and only one identity – that it can only be one kind of thing – and that an object’s identity is revealed by object labels” (Markman 1989, p. 212); Similarly John Flavell: “the child may think that the word kitty describes or characterizes the single way that cats are, and consequently that calling them “cat” or “animal” amounts to claiming that they are some other way than that. It is possible, therefore, that young children are loath to accept two category names for the same thing, for much the same reason they are loath to accept two perspectives, or both the appearance and the reality, as two equally valid characterizations of the same thing: namely, because one thing has only one nature and should therefore be characterized in only one way.” (Flavell 1988, p. 254).

In the case of “white” another interpretation is possible, namely that one is not talking about the rabbit but about its colour, i.e., “This is white” means “the colour I am pointing at is white.” Although possible it does not seem to occur in the contexts used in the alternative naming game.

This is not to be understood as an argument that it has to be that way, but that alternative filing is a possible and perhaps sensible option.

Linking of files is not restricted to only two files. Our account is, therefore, not limited to two alternative labels in the alternative naming game. In fact, children could have individuated the objects in other ways, e.g., as a pet, a living thing, etc. This would not impinge on our theoretical claims. It just turns out that children this age typically do not venture beyond the terms that have been used in the pretest.

When in a discourse an object is being individuated or referred to under a particular label the corresponding discourse file is activated. A basic mechanism of entrainment or alignment (Pickering and Garrod 2004) obliges the discourse participants to keep conceptualizing the object under this file in order to keep common ground and to not mix different perspectives. These alignment processes have also been described as “conceptual pacts” (Brennan and Clark 1996)

Starting with Clements and Perner (1994) earlier competence could be demonstrated when children are not asked a question about the protagonist, but children’s looking behavior is registered, i.e., where they look in expectation of where the protagonist will go, or that they look longer when something unexpected happens than when the expected happens (Onishi and Baillargeon 2005). The interpretation of these data is hotly debated, most recently: Baillargeon et al. 2010; Butterfill and Apperly 2013; Helming et al. 2014; Perner and Roessler 2012; Ruffman 2014.

Pretending that the Lego block is a bar of chocolate could be represented with a discourse file that has no referent (representing a fictional entity) but being anchored by stipulation (no serious recognitional processes) to the Lego piece as a prop. The discourse file functions as part of a discourse: if I pour water over the chocolate it will be wet (Harris and Kavanaugh 1993), etc. The anchoring serves to direct the actions represented in the files to the props.

Perner et al. (2007) e.g., p 488) dealt with vertical linking by having identifiers for each regular file and vicarious files bearing the same identifier, indicating that they share the same referent. But this method falls short of specifying anything about information flow between files.

This sequence is plausible unless we subscribe to simulation theory. Simulation makes it possible to put oneself into the agent’s perspective of ignorance about the die being an eraser and, hence, one would not generate a regular eraser file during simulation and, consequently, not tempted to create a vicarious eraser file.

References

Aichhorn, M., J. Perner, B. Weiss, M. Kronbichler, W. Staffen, and G. Ladurner. 2009. Temporo-parietal junction activity in theory-of-mind tasks: falseness, beliefs, or attention. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 21(6): 1179–1192. doi:10.1162/jocn.2009.21082.

Apperly, I.A., and E. Robinson. 2002. Five-year-olds’ handling of reference and description in the domains of language and mental representation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 83(1): 53–75. doi:10.1016/S0022-0965(02)00102-9.

Baillargeon, R., R.M. Scott, and Z. He. 2010. False-belief understanding in infants. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 14(3): 110–118. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.006.

Baron-Cohen, S., H.A. Ring, S. Wheelwright, E.T. Bullmore, M.J. Brammer, A. Simmons, and S.C. Williams. 1999. Social intelligence in the normal and autistic brain: an fMRI study. European Journal of Neuroscience 11: 1891–1898.

Brennan, S.E., and H.H. Clark. 1996. Conceptual pacts and lexical choice in conversation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 22: 1482–1493.

Brunet, E., Y. Sarfati, M.C. Hardy-Baylé, and J. Decety. 2000. A PET investigation of the attribution of intentions with a nonverbal task. NeuroImage 11: 157–166.

Butterfill, S.A., and I.A. Apperly. 2013. How to construct a minimal theory of mind. Mind & Language 28: 606–637.

Cabeza, R., E. Ciaramelli, and M. Moscovitch. 2012. Cognitive contributions of the ventral parietal cortex: an integrative theoretical account. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 16: 338–352. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.04.008.

Chandler, M.J., and D. Helm. 1984. Developmental changes in the contribution of shared experience to social role-taking competence. International Journal of Behavioral Development 7: 145–156.

Clark, E.V. 1997. Conceptual perspective and lexical choice in acquisition. Cognition 64: 1–37.

Clements, W.A., and J. Perner. 1994. Implicit understanding of belief. Cognitive Development 9: 377–397.

Doherty, M. 1994. Metalinguistic understanding and theory of mind. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Laboratory of Experimental Psychology, University of Sussex.

Doherty, M.J., and J. Perner. 1998. Metalinguistic awareness and theory of mind: Just two words for the same thing? Cognitive Development 13: 279–305.

Flavell, J.H. 1988. The development of children’s knowledge about the mind: From cognitive connections to mental representations. In Developing theories of mind, ed. J.W. Astington, P.L. Harris, and D.R. Olson, 244–267. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gordon, R.M. 1986. Folk psychology as simulation. Mind & Language 1: 158–171.

Gordon, R.M. 1995. Simulation without introspection or inference from me to you. In Mental simulation: Evaluations and applications, ed. M. Davies and T. Stone, 53–67. Oxford: Blackwell.

Gordon, A.C., and D.R. Olson. 1998. The relation between acquisition of a theory of mind and the capacity to hold in mind. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 68: 70–83.

Harris, P.L., and R.D. Kavanaugh. 1993. Young children’s understanding of pretence. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 58(1): 1–107.

Heal, J. 1986. Replication and functionalism. In Language, mind, and logic, ed. J. Butterfield, 135–150. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heim, I. 2002. File change semantics and the familiarity theory of definiteness. In Formal semantics: The essential readings, ed. P. Portner and B.H. Partee, 223–248. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Helming, K.A., B. Strickland, and P. Jacob. 2014. Making sense of early false-belief understanding. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 18(4): 167–170.

Kamp, H. 1990. Prolegomena to a structural account of belief and other attitudes. In Propositional attitudes: The role of content in logic, language and mind, ed. C.A. Anderson, 27–90. Stanford: Center for study of language and information, Lecture Notes Series.

Kamp, H., and U. Reyle. 1993. From discourse to logic. introduction to model theoretic semantics of natural language, formal logic and discourse representation theory. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Kanwisher, N. 2010. Functional specificity in the human brain: a window into the functional architecture of the mind. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107(25): 11163–11170. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005062107.

Karttunen, L. 1976. Discourse referents. In Notes from the linguistic underground (Syntax and semantics, vol. 7), ed. J. McCawley, 363–385. Waltham, MA: Academic Press.

Leslie, A.M. 1987. Pretense and representation: The origins of “theory of mind”. Psychological Review 94: 412–426.

Markman, E.M. 1989. Categorization and naming in children: Problems of induction. Cambridge: A Bradford Book.

Millikan, R.G. 2000. On clear and confused ideas. an essay about substance concepts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Onishi, K.H., and R. Baillargeon. 2005. Do 15-month-old infants understand false beliefs? Science 308: 255–258.

Perner, J., and J. Brandl. 2005. File change semantics for preschoolers: Alternative naming and belief understanding. Interaction Studies 6: 483–501.

Perner, J., and G. Davies. 1991. Understanding the mind as an active information processor: Do young children have a “copy theory of mind”? Cognition 39: 51–69.

Perner, J., and J. Roessler. 2012. From infants’ to children’s appreciation of belief. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 16(10): 519–525. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.08.004.

Perner, J., and H. Wimmer. 1988. Misinformation and unexpected change: testing the development of epistemic-state attribution. Psychological Research 50: 191–197. doi:10.1007/BF00310181.

Perner, J., S. Stummer, M. Sprung, and M.J. Doherty. 2002. Theory of mind finds its Piagetian Perspective: Why alternative naming comes with understanding belief. Cognitive Development 17: 1451–1472.

Perner, J., M. Aichhorn, M. Kronbichler, W. Staffen, and G. Ladurner. 2006. Thinking of mental and other representations: The roles of left and right temporo-parietal junction. Social Neuroscience 1: 245–259. doi:10.1080/17470910600989896.

Perner, J., B. Rendl, and A. Garnham. 2007. Objects of desire, thought, and reality: Problems of anchoring discourse referents in development. Mind & Language 22: 475–513.

Perner, J., M.C. Mauer, and M. Hildenbrand. 2011. Identity: Key to children’s understanding of belief. Science (New York, N.Y.) 333(6041): 474–477. doi:10.1126/science.1201216.

Perry, J. 2002. Identity, personal identity and the self. Cambridge: Hackett Publishing.

Pickering, M.J., and S. Garrod. 2004. Toward a mechanistic psychology of dialogue. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 27(02): 169–190.

Pylyshyn, Z.W. 2007. Things and places: How the mind connects with the world. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Rakoczy, H., D. Bergfeld, I. Schwarz, and E. Fizke. 2015. Explicit theory of mind is even more unified than previously assumed: Belief ascription and understanding aspectuality emerge together in development. Child Development. doi:10.1111/cdev.12311.

Recanati, F. 2012. Mental files. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Robinson, E.J., and I.A. Apperly. 2001. Children’s difficulties with partial representations in ambiguous messages and referentially opaque contexts. Cognitive Development 16: 595–615.

Ruffman, T. 2014. To belief or not belief: Children’s theory of mind. Developmental Review 34(3): 265–293. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2014.04.001.

Russell, J. 1987. ‘Can we say …?’ children’s understanding of intensionality. Cognition 25: 289–308.

Saxe, R., and N. Kanwisher. 2003. People thinking about thinking people: The role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind.”. NeuroImage 19: 1835–1842. doi:10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00230-1.

Schurz, M., M. Aichhorn, A. Martin, and J. Perner. 2013. Common brain areas engaged in false belief reasoning and visual perspective taking: a meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7: 712. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00712.

Schurz, M., J. Radua, M. Aichhorn, F. Richlan, and J. Perner. 2014. Fractionating theory of mind: A meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 42C: 9–34. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.01.009.

Sodian, B., and H. Wimmer. 1987. Children’s understanding of inference as a source of knowledge. Child Development 58: 424–433.

Sprung, M., J. Perner, and P. Mitchell. 2007. Opacity and embedded perspectives: Object identity and object properties. Mind & Language 22: 215–245.

Stummer, S. 2001. Sag es anders - ToM! von einem metalinguisitschem bewusstsein zu alternativen erklärungsansätzen. Dissertation, University of Salzburg.

Taylor, M. 1988. Conceptual perspective taking: Children’s ability to distinguish what they know from what they see. Child Development 59: 703–718.

Tomasello, M. 1999. The cultural origins of human cognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wellman, H.M., D. Cross, and J. Watson. 2001. Meta-analysis of theory of mind development: the truth about false belief. Child Development 72: 655–684. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00304.

Wimmer, H., and J. Perner. 1983. Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition 13: 103–128.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perner, J., Leahy, B. Mental Files in Development: Dual Naming, False Belief, Identity and Intensionality. Rev.Phil.Psych. 7, 491–508 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-015-0235-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-015-0235-6