Abstract

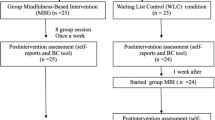

An important presumed mechanism of change in mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) is the extent to which participants learn to respond mindfully (i.e., return attention to a nonjudgmental present-oriented awareness) in daily life. Because existing measures that assess mindful responding are not sensitive to contextual fluctuations that occur in people’s daily lives, little is still known about how people’s ability to respond mindfully to daily events changes with mindfulness training and what role this change plays in explaining the benefits of MBIs. The purpose of the current study was to develop a brief measure that can be administered on a daily basis throughout an MBI to assess the extent to which people respond mindfully in their daily lives. We report initial psychometric properties for this measure, named the Daily Mindful Responding Scale (DMRS). One hundred seventeen participants who took part in a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program completed daily diaries that included the DMRS and measures of psychological distress and wellbeing. They also completed measures of psychological distress and wellbeing pre- and post-MBSR. Using multilevel analyses, we examined various indices of reliability and validity of the DMRS. The findings support the reliability and validity of the DMRS at both between- and within-person levels of analysis. Importantly, DMRS scores steadily increased throughout the MBSR program and this increase predicted a reduction in psychological distress and an increase in psychological wellbeing. Limitations and future directions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baer, R. (Ed.). (2010). Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: illuminating the theory and practice of change. Oakland: Context Press/New Harbinger.

Baer, R., Smith, G., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45.

Baer, R., Smith, G., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342.

Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary methods: capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 579–616. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030.

Borsboom, D., Mellenbergh, G. J., & van Heerden, J. (2003). The theoretical status of latent variables. Psychological Review, 110(2), 203–219. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.203.

Brennan, R. L. (2001). An essay on the history and future of reliability from the perspective of replications. Journal of Educational Measurement, 38(4), 295–317.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. doi:10.1080/10478400701598298.

Carmody, J., Baer, R. A., Lykins, E. L. B., & Olendzki, N. (2009). An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(6), 613–626. doi:10.1002/jclp.20579.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Cranford, J. A., Shrout, P. E., Iida, M., Rafaeli, E., Yip, T., & Bolger, N. (2006). A procedure for evaluating sensitivity to within-person change: can mood measures in diary studies detect change reliably? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(7), 917–929.

Cronbach, L. J., Gleser, G. C., Nanda, H., & Rajaratman, N. (1972). The dependability of behavioral measurements: theory of generalizability for scores and profiles. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Erisman, S. M., & Roemer, L. (2012). A preliminary investigation of the process of mindfulness. Mindfulness, 3(1), 30–43.

Fjorback, L. O., Arendt, M., Ørnbøl, E., Fink, P., & Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(2), 102–119. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x.

Fresco, D., Moore, M., van Dulmen, M., Segal, Z., Ma, S., Teasdale, J., & Williams, M. (2007). Initial psychometric properties of the Experiences Questionnaire: validation of a self-report measure of decentering. Behavior Therapy, 38, 234–246.

Garland, E. L., Manusov, E. G., Froeliger, B., Kelly, A., Williams, J. M., & Howard, M. O. (2014). Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(3), 448–459. doi:10.1037/a0035798.

Goldstein, J., & Kornfield, J. (1987). Seeking the heart of wisdom. Boston: Shambhala.

Hoyle, R. H., & Panter, A. T. (1995). Writing about structural equation models. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling, concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 158–176). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: the program of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. New York: Delta.

Keng, S. L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1041–1056. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006.

Khoury, B., Lecomte, T., Fortin, G., Masse, M., Therien, P., Bouchard, V., et al. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005.

Miller, C. K., Kristeller, J. L., Headings, A., & Nagaraja, H. (2014). Comparison of a mindful eating intervention to a diabetes self-management intervention among adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Health Education & Behavior, 41(2), 145–154. doi:10.1177/1090198113493092.

Moskowitz, D. S., Russell, J. J., Sadikaj, G., & Sutton, R. (2009). Measuring people intensively. Canadian Psychology, 50(3), 131–140. doi:10.1037/a0016625.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2013). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Reis. (2012). Why researchers should think “real-world”: a conceptual rationale. In T. Mehl & T. Conner (Eds.), Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (pp. 3–21). New York: Guilford Press.

Salmon, P. G., Sephton, S. E., & Dreeben, S. J. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction. In J. D. Herbert & E. M. Forman (Eds.), Acceptance and mindfulness in cognitive behavior therapy: understanding and applying the new therapies (pp. 132–163). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

SAS Institute Inc. (2013). What’s new in SAS® 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2010). Ensuring positiveness of the scaled difference chi-square test statistic. Psychometrika, 75(2), 243–248. doi:10.1007/BF02296192.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford.

Shavelson, R. J., & Webb, N. M. (1991). Generalizability theory: a primer. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Thompson, E. (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(2), 227–242.

Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Ravert, R. D., Williams, M. K., Bede Agocha, V., et al. (2010). The questionnaire for eudaimonic well-being: psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 41–61. doi:10.1080/17439760903435208.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a doctoral fellowship from the Fonds québécois de la recherche sur la société et la culture (FQRSC) to the first author and a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC 410-2009-2226) to the last author. The authors would like to thank Kimberly Carrière for her assistance with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

General Instructions

Before filling out your daily diary, you will be asked to take a moment and actively remember your day. It is not important that you go in too much detail, but just to get a good idea of the main highlights of the day. You will need to refer to this information for all of the diary questions, so it is crucial that you do not overlook this step.

You will respond to the same questions in your diary every day for the duration of the MBSR program. It is therefore important that you have a good understanding of what the questions in the diary mean. Below is an explanation of the items on the first page of the diary. The four items on the first page of the diary are structured similarly to each other, with the first part referring to when you encountered certain experiences, and the second part, referring to how you responded to such experiences.

ITEM 1: Today, when my mind was caught up in thoughts, I let go of them and brought my awareness back to the present moment. We often get caught up in certain thoughts, stories, or plans that we think about. This is very common. What the item asks, is when that happened, what did you do afterwards? While sometimes we get lost in our thoughts, at other times, we notice that we are lost in thought. So we purposefully let go of them and reconnect with the present moment. We are actively becoming aware of what is happening either in our body or in our environment. This question refers to becoming aware in this way. To answer this item, you must (1) think of the times in the day when you were caught up in thoughts and (2) remember, out of those times, how often did you actively disengage from mental activity and instead redirect your awareness to your body or your environment.

ITEM 2: Today, when I had unpleasant feelings, I observed them as they were, without trying to avoid or change them. During the day, we often experience unpleasant feelings such as sadness, anxiety, stress, pain, jealousy, impatience, anger, discomfort, and boredom, among others. To deal with those feelings, sometimes, we do things to avoid or change them, such as taking painkillers to alleviate pain, eating to comfort ourselves, watching a funny movie not to feel so sad, and so on. Other times, we don’t try to get rid of such unpleasant feelings or try to change them, but just let them be there, and in some way, acknowledge them as we go about our day. This item refers to this kind of “opening up to” unpleasant experiences as they are. To answer this item, you must (1) think about what unpleasant feelings you had during the day and (2) remember how you reacted to these unpleasant feelings. How often were you open to these unpleasant feelings, and let them be there without attempting to get rid of them or change them in any way?

ITEM 3: Today, when I was being critical of myself or others, I let go of judgments to become more accepting instead. We are all inherently judgmental towards ourselves and others. This is normal, as we have little control over our initial judgments. What this item asks is once you had initially been critical towards yourself or others, what did you do afterwards? Sometimes we continue to be judgmental and criticize ourselves or others. Other times, we notice that we were being judgmental and instead actively interrupt being critical to become more accepting of ourselves or others. This is much like forgiving ourselves or others for doing things we don’t approve. Note that this item does not imply that you became accepting, only that you intended to, by letting go of judgments. So this item refers to actively letting go of judgments after being critical. To answer this item, you must (1) think back at the times you were critical of yourself and/or others during the day and (2) remember how often you then let go of these judgments.

ITEM 4: Today, when I was absorbed in thoughts or emotions, I “stepped back” from them so that I could see them more clearly, without being drawn into them. Thoughts associated with strong emotions, such as when we are worrying, ruminating, or going through difficult scenarios, have a certain quality that makes it easy for us to become absorbed in. When we do, we forget that they are thoughts (i.e., representations), and we mistake them for being real. For example, worrying about losing your job is not the same thing as actually losing your job; it is in fact simply a thought with an associated emotion. Sometimes, when we get absorbed in these strong thoughts, we can simply become aware of them as thoughts going by in our heads and not get caught up in what they mean. This is like “zooming out” of our thoughts and seeing them from a greater distance, so that, in a way, they lose their power. So this question asks how often you attempted to zoom out of those “stories” so that you could see your thoughts as “just thoughts”. To answer this item, you must (1) think about times in the day when you were absorbed in thoughts associated with strong emotions and (2) remember how often you then actively distanced yourself from these thoughts and were able to just see them as mental activity going on in your mind.

Daily Mindful Responding Scale (DMRS)

Take a few moments to recall your day and then fill out today’s diary.

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

rarely | often |

-

1.

Today, when my mind was caught up in thoughts, I let go of them and brought my awareness back to the present moment.

-

2.

Today, when I had unpleasant feelings, I observed them as they were, without trying to avoid or change them.

-

3.

Today, when I was being critical of myself or others, I let go of judgments to become more accepting instead.

-

4.

Today, when I was absorbed in thoughts or emotions, I "stepped back" from them so that I could see them more clearly, without being drawn into them.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lacaille, J., Sadikaj, G., Nishioka, M. et al. Measuring Mindful Responding in Daily Life: Validation of the Daily Mindful Responding Scale (DMRS). Mindfulness 6, 1422–1436 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0416-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0416-5