Abstract

Although Asian Indians constitute one of the largest and fastest-growing immigrant groups in the United States, there has been no systematic examination of their economic performance. This paper studies the relative wage convergence of Asian Indians in the United States, using the 5/100 1990 and 2000 US Censuses. Results from cross-sectional and cohort analyses indicate that, although the recent-arrival cohort of Asian Indian males and females face a wage penalty relative to native-born non-Hispanic whites, there is significant growth in their wages over the decade, suggesting strong economic assimilation. However, overall, the group is not able to reach wage parity with comparable native-born whites even after residing in the country for 20 years. These results are in line with the existing evidence on post-1965 immigrants in the United States. Furthermore, results indicate that Asian Indians experience greater wage assimilation compared with Other Asians, and within the Asian Indian group, females experience greater economic assimilation compared with males.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, of the 1.5 million Asian Indian foreign-born in the United States in 2006, 34.4% entered the country in 2000 or later, 35.6% entered between 1990 and 1999, 17.3% between 1980 and 1989, 9.7% between 1970 and 1979, and the remaining 3.0% prior to 1970 (Terrazas 2008).

Henceforth, “Other Asians” refer to Asians excluding Asian Indians; and “Asians” refer to Asians including Asian Indians.

As a result of the 1965 Act, the United States began accepting immigrants based on the applicant’s family ties with US residents or citizens. The 1965 Act abolished the national-origin quotas that had been in place in the United States since the Immigration Act of 1924. The Act of 1924 limited the number of immigrants who could be admitted from any country to 2 % of the number of people from that country who were already living in the United States in 1890, according to the Census of 1890. The 1924 Act, coupled with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, had virtually excluded all immigration from Asia.

Eastern Asian immigrants originated from China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, South Korea, North Korea, Macau, Mongolia, Paracel Islands, and Taiwan. Southeastern Asian immigrants originated from Brunei, Myanmar (Burma), Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam (Terrazas 2008).

In 1960, there were 104,843 immigrants from Southeastern Asia and 220,081 immigrants from Eastern Asia; these increased to 184,842 and 331,078 in 1970, respectively. Compared with these, there were only 14,004 immigrants from South Central Asia (including India) in 1960; these increased to 57,182 in number in 1970 (Dixon 2006).

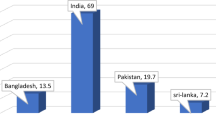

Between 1990 and 2000, there were 562,320 immigrant-arrivals from India, 556,480 from China, and 483,360 from the Philippines (Dixon 2006).

Note also that the number of unauthorized immigrants from India grew faster than the number of any other immigrant group between 2000 and 2006 (Terrazas 2008).

The vast majority of group-specific studies on immigrant assimilation in the US have dealt with Mexican immigration in general or various Hispanic groups in particular (Borjas 1982; Allensworth 1997; Lazear 2007). This is because, traditionally, Mexico has been the largest source of immigrants in the United States.

Also see Saran (1985).

In Eq. 1, ξ t consists of time, vintage, and cohort effects. In a single cross-section, these effects are not separately identified. To eliminate cohort effects, one can follow the wage growth of an arrival-cohort (a synthetic panel methodology) between two census years; this wage growth needs to be indexed against a base group such as Native-born whites. This quasi-panel procedure eliminates cohort effects. To separately identify the vintage (or assimilation) effects, an additional identifying assumption is required: There is no time effect on the relative wages of immigrants. In other words, relative wage changes caused by changes on market conditions are assumed to be the same for immigrants and the base group. For a detailed discussion, see LaLonde and Topel (1992).

For both 1990 and 2000, j = 5. Data on immigrants is divided into 5 arrival cohorts: cohort 1–5 (j = 1), cohort 6–10 (j = 2), cohort 11–15 (j = 3), cohort 16–20 (j = 4), and Cohort 20+ (j = 5), where cohort 1–5 represents immigrants who have been in the U.S. for one to five years and Cohort 20+ represents immigrants who have been in the U.S. for more than 20 years.

If estimated \( \widehat{\delta } \) 3, 1990 > estimated \( \widehat{\delta } \) 1, 1990, this implies that the difference in wages between immigrants and the native-born whites has gone down over a period of 10 years. Moreover, if (\( \widehat{\delta } \) 3, 1990− \( \widehat{\delta } \) 1, 1990) >0, this suggests positive relative wage growth for immigrants over a ten year period.

If (\( \widehat{\delta } \) 3, 2000− \( \widehat{\delta } \) 1, 1990) >0, this suggests positive relative wage growth for the most recent immigrant arrival cohort in 1990, over a ten year period. Note that these results are based on ‘within’ cohort estimates, by tracking cohorts across Census years.

Note that in the two Censuses, “years since migration” and various immigrant arrival cohorts are indistinguishable. In Eq. 1, both these effects are absorbed by the set of arrival cohort dummies.

‘Years of schooling’ (YS) was calculated using Angrist, Chernozhukov and Fernandez-Val’s (2006) methodology: No schooling = 0 YS; Nursery to Grade 4 = 4 YS; Grades 5 to 8 = 8 YS; Grade 9 = 9YS; Grade 10 = 10 YS; Grade 11/ Grade 12, no diploma = 11 YS; High School/GED = 12 YS; Some college/no degree = 13 YS; Associate degree-occupational = 14 YS; Associate degree-academic = 15 YS; Bachelor’s = 20 YS degree = 17 YS; Masters degree = 18 YS; Professional degree = 19 YS; and Doctorate = 20 YS

English language skills, an individual’s occupation and industry are not included in Eq. (1) since these may be part of the process through which immigrants improve their earnings over time.

For 1990, the two cross-sectional estimates for the 10-year assimilation period are: (a) \( \widehat{\delta } \) 3, 1990− \( \widehat{\delta } \) 1, 1990 and (b) \( \widehat{\delta } \) 4, 1990− \( \widehat{\delta } \) 2, 1990. For 2000, the two cross-sectional estimates for the 10-year assimilation period are: (a) \( \widehat{\delta } \) 3, 2000− \( \widehat{\delta } \) 1, 2000 and (b) \( \widehat{\delta } \) 4, 2000− \( \widehat{\delta } \) 2, 2000. The two within-growth estimates are (a) \( \widehat{\delta } \) 3, 2000− \( \widehat{\delta } \) 1, 1990 and (b) \( \widehat{\delta } \) 4, 2000− \( \widehat{\delta } \) 2, 1990.

References

Allensworth, E. M. (1997). Earnings mobility of first and “1.5” generation Mexican-origin women and men: A comparison with U.S.-born Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. International Migration Review, 31(2), 386–410.

Angrist, J., Chernozhukov, V., & Fernandez-Val, I. (2006). Supplement to “quantile regression under misspecification, with an application to the U.S. wage structure”: Variable definitions, data, and programs. Econometrica, 74(2), 539–563.

Baker, M., & Benjamin, D. (1994). The performance of immigrants in the Canadian labor market. Journal of Labor Economics, 12(3), 369–405.

Barringer, H., & Kassebaum, G. (1989). Asian Indians as a minority in the United States: The effect of education, occupations and gender on income. Sociological Perspectives, 32(4), 501–520.

Betts, J. R., & Lofstrom, M. (2000). The education attainment of immigrants: Trends and implications. In G. Borjas (Ed.), Issues in the economics of immigration (pp. 51–116). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Borjas, G. (1982). The earnings of male Hispanic immigrants in the United States. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 35(3), 343–353.

Borjas, G. (1985). Assimilation, changes in cohort quality, and the earnings of immigrants. Journal of Labor Economics, 3(4), 463–489.

Borjas, G. (1993). Immigration policy, national origin, and immigrant skills: A comparison of Canada and the United States. In D. Card & R. B. Freeman (Eds.), Small differences that matter: Labor markets and income maintenance in Canada and the United States (chapter 1). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Borjas, G., & Bratsberg, B. (1996). Who leaves? The outmigration of the foreign-born. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 68, 165–176.

Borjas, G., & Freeman, R. (1992). Introduction and summary. In G. Borjas & R. Freeman (Eds.), Immigration and the work force: Economic consequences for the United States and source areas (pp. 1–15). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chiswick, B. (1978). The effect of Americanization on the earnings of foreign-born men. Journal of Political Economy, 86(5), 897–922.

Dixon, D. (2006). Characteristics of the Asian born in the United States. Migration Policy Institute Resource Document. http://www.migrationinformation.org/USFocus/display.cfm?ID=378. Accessed 12 January 2010.

Dworkin, A., & Dworkin, J. (1988). Interethnic stereotypes of acculturating Asian Indians in the United States. Plural Societies, 18(1), 61–70.

Iceland, J. (1999). Earnings returns to occupational status: Are Asian Americans disadvantaged? Social Science Research, 28(1), 45–65.

Jasso, G., & Rosenzweig, M. (1982). Estimating the emigration rates of legal immigrants using administrative and survey data: The 1971 cohort of immigrants to the US. Demography, 19, 279–290.

Kim, C., & Sakamoto, A. (2010). Have Asian American men achieved labor market parity with Whites? American Sociological Review, 75, 934–957.

LaLonde, R., & Topel, R. (1992). The assimilation of immigrants in the U.S. labor markets. In G. Borjas & R. Freeman (Eds.), Immigration and the workforce (pp. 67–92). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lazear, E. P. (2007). Mexican assimilation in the United States. In G. Borjas (Ed.), Mexican immigration to the United States (pp. 107–122). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ruggles, S., Sobek, M., Alexander, T., Fitch, C., Goeken, R., Hall, P., et al. (2008). Integrated public use microdata series: Version 4.0 [machine-readable database]. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center [producer and distributor], 2008.

Saran, P. (1985). The Asian Indian experience in the United States. Cambridge: Schenkman Publishing.

Saran, P., & Eames, E. (1980). The new ethnics: Asian Indians in the United States. New York: Praeger Publishers.

Schoeni, R. F. (1997). New evidence on the economic progress of foreign-born men in the 1970s and 1980s. Journal of Human Resources, 66(2), 683–740.

Singh, G., & Augustine, K. (1996). Occupation-specific earnings attainment of Asian Indians and Whites in the United States: Gender and nativity differentials across Class Strata. Applied Behavioral Science Review, 4(2), 137–175.

Terrazas, A. (2008). Indian immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Institute Resource Document. http://www.migrationinformation.org/USFocus/display.cfm?ID=687. Accessed 12 January 2010.

Wadhwa, V., Jain, S., Saxenian, A., Gereffi, G., Wang, H. (2011). The Grass is indeed greener in India and China for returnee entrepreneurs: America’s new immigrant entrepreneurs, part VI. The Kauffman Foundation. http://www.kauffman.org/uploadedfiles/grass-is-greener-for-returnee-entrepreneurs.pdf. Accessed June 20, 2012.

Zeng, Z., & Xie, Y. (2004). Asian-Americans’ earnings disadvantage reexamined: The role of place of education. The American Journal of Sociology, 109(5), 1075–1108.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Sping Wang for her help with the manuscript. The author is also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tiagi, R. Economic Assimilation of Asian Indians in the United States: Evidence from the 1990s. Int. Migration & Integration 14, 511–534 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-012-0252-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-012-0252-6