Abstract

Purpose

Health care needs of adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer are probably different from other age groups. Studying their non-oncology physician visits in the first years after diagnosis may provide insight into the specific health problems AYA patients experience and thereby help to improve care for these patients.

Methods

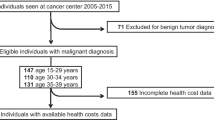

Seven hundred seventy-four AYAs identified from a Canadian provincial registry diagnosed with cancer between ages 15 and 24 years in 1991/2001 were included, matched by birth year and sex to ten controls. Based on provincial health insurance plan records, we determined the number of family physician and non-cancer specialist visits in the 5 years after diagnosis (for patients) or inclusion (for controls).

Results

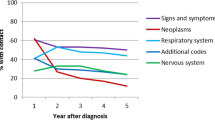

The percentage of patients visiting a non-cancer specialist decreased from 96 to 49 % over the 5-year period. The percentage visiting a family physician decreased from 96 to 84 %. Visits in all years were significantly higher than among controls. In the first year after diagnosis, many patients visited a non-cancer specialist or a family physician for neoplasm-related health problems (77 and 55 %, respectively). In addition, family physicians were also consulted for general age-specific problems, such as genitourinary symptoms

Conclusions

In the first years after diagnosis of cancer in AYAs, both non-cancer specialist and family physician visits are common, although non-cancer specialist visits are less common and decline considerably faster than in younger children.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

The specific pattern of physician visits of this age group calls for care that is tailored to their specific needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hampton T. Cancer treatment’s trade-off: years of added life can have long-term costs. JAMA. 2005;294:167–8.

Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2014. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society; 2014.

Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. Closing the gap: research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer (NIH Publication No. 06-6067). Bethesda MD: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the LiveStrong Young Adult Alliance, 2006.

Haase JE, Phillips CR. The adolescent/young adult experience. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2004;21:145–9.

Thomas DM, Seymour JF, O’Brien T, Sawyer SM, Ashley DM. Adolescent and young adult cancer: a revolution in evolution? Int Med J. 2006;36:302–7.

Zebrack B, Hamilton R, Smith AW. Psychosocial outcomes and service use among young adults with cancer. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:468–77.

Zebrack B, Bleyer A, Albritton K, Medearis S, Tang J. Assessing the health care needs of adolescent and young adult cancer patients and survivors. Cancer. 2006;107:2915–23.

Fritz GK, Williams JR. Issues of adolescent development for survivors of childhood cancer. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27:712–5.

Madan-Swain A, Brown RT, Foster MA, et al. Identity in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25:105–15.

Kazak AE, Derosa BW, Schwartz LA, et al. Psychological outcomes and health beliefs in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer and controls. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2002–7.

Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan TH, et al. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in the United States: the adolescent and young adult health outcomes and patient experience study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2136–45.

Phillips-Salimi CR, Andrykowski MA. Physical and mental health status of female adolescent/young adult survivors of breast and gynecological cancer: a national, population-based, case-control study. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1597–604.

Tai E, Buchanan N, Townsend J, Fairley T, Moore A, Richardson LC. Health status of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118:4884–91.

Tonorezos ES, Oeffinger KC. Research challenges in adolescent and young adult cancer survivor research. Cancer. 2011;117:2295–300.

Zebrack B, Mathews-Bradshaw B, Siegel S, Alliance LYA. Quality cancer care for adolescents and young adults: a position statement. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4862–7.

Rebholz CE, Reulen RC, Toogood AA, et al. Health care use of long-term survivors of childhood cancer: the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4181–8.

McBride ML, Lorenzi MF, Page J, et al. Patterns of physician follow-up among young cancer survivors: report of the Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancer Survivors (CAYACS) research program. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:e482–90.

Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, et al. Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:61–70.

Shaw AK, Pogany L, Speechley KN, Maunsell E, Barrera M, Mery LS. Use of health care services by survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer in Canada. Cancer. 2006;106:1829–37.

Nathan PC, Hayes-Lattin B, Sisler JJ, Hudson MM. Critical issues in transition and survivorship for adolescents and young adults with cancers. Cancer. 2011;117:2335–41.

McBride ML, Rogers PC, Sheps SB, et al. Childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors research program of British Columbia: objectives, study design, and cohort characteristics. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:324–30.

Rogers PC, De Pauw S, Schacter B, Barr RD. A process for change in the care of adolescents and young adults with cancer in Canada. “Moving to Action”: The Second Canadian International Workshop. International Perspectives on AYAO, Part 1. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2013;2:72–6.

International classification of diseases and health related problems. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992.

Lawless JF. Negative binomial and mixed Poisson regression. Can J Stat. 1987;15:209–25.

Heins MJ, Lorenzi MF, Korevaar JC, McBride ML. Non-oncology physician visits after diagnosis of cancer in children. BMC Family practice. 2016. (Accepted for publication).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Funding for this study was received from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Cancer Society (through the National Cancer Institute of Canada), and the Dutch Cancer Society.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards and Canadian legislation on privacy. BC Cancer Agency (BCCA) and BC Children’s Hospital (BCCH) clinical Research Ethics Boards, both part of the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board, approved of the study. BC Cancer Agency, BC Children’s Hospital, and BC Ministry of Health approved access to and use of the data, facilitated by Population Data BC, for this study.

Informed consent

Given the large number of participants, obtaining individual informed consent was not feasible. To protect patient confidentiality, only de-identified linked files were available to the researchers and the Ministry of Health required suppression of cells with fewer than five patients in the text and tables.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Heins, M.J., Lorenzi, M.F., Korevaar, J.C. et al. Non-oncology physician visits after diagnosis of cancer in adolescents and young adults. J Cancer Surviv 10, 783–788 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0523-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0523-x