Abstract

What was the contribution of intercontinental trade to the development of the European early modern economies? Previous attempts to answer this question have focused on static measures of the weight of trade in the aggregate economy at a given point in time, or on the comparison of the income of specific imperial nations just before and after the loss of their overseas empire. These static accounting approaches are inappropriate if dynamic and spillover effects are at work, as seems likely. In this paper, I use a panel dataset of 10 countries in a dynamic model that allows for spillover effects, multiple channels of causality, persistence, and country-specific fixed effects. Using this dynamic model, simulations suggest that in the counterfactual absence of intercontinental trade, rates of early modern economic growth and urbanization would have been moderately to substantially lower. For the four main long-distance traders, by 1800, the real wage was, depending on the country, 6.1–22.7 % higher, and urbanization was 4.0–11.7 percentage points higher, than they would have otherwise been. For some countries, the effect was quite pronounced: in The Netherlands between 1600 and 1750, for instance, intercontinental trade was responsible for most of the observed increase in real wages and for a large share of the observed increase in urbanization. At the same time, countries which did not engage in long-distance trade would have had real wage increases in the order of 5.4–17.8 % and urbanization increases of 2.2–3.2 percentage points, should they have done so at the same level as the four main traders. Intercontinental trade appears to have played an important role for all nations that engaged in it, with the exception of France. These conclusions stand in contrast to the earlier literature that uses a partial equilibrium and static accounting approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For instance, suppose an urban trade boom raises wages and then induces rapid development of labor-saving technological change. This growth-enhancing effect is completely absent from static calculations, which would incorrectly conclude that without trade, all else would be constant: GDP would only decrease by the amount of that trade.

Notice the difference in units: it is more convenient to express effects on urbanization in percentage point increases, since the original unit is itself already a percentage.

I have used the most recent data available for the simulations in this paper.

One easily overlooked issue is that one advantage of having an empire was to have access to imports (particularly for raw materials) at prices below what the “free trade” market price would have been, and to have access to a privileged market for exports. Hence, the impact of intercontinental trade on economic growth and urbanization estimated here may have been conditional on the nature of the trade practices of the time.

To this, I would add that the dependency theorists’ emphasis on the critical importance of capital accumulation is also difficult to square with the discovery of Solow (1957) that TFP change, not capital accumulation, is the main driver of economic growth—though of course, Solow’s data, as that of most of the growth-accounting literature, refer to modern economies. See, however, Bond et al. (2010).

During the early modern period, much of the long-distance, oceanic trade was not “colonial” in nature, instead operating by means of merchant companies. I thank an anonymous referee for clarifying that for this reason, it would be best to call it “intercontinental,” rather than “colonial,” trade.

Indeed, when answering the question, it is important not to control for intermediate outcomes. The question of what was the dynamic impact of trade on income, while keeping urbanization constant both in the past and in the present, is not an interesting one if much of the effect of trade on growth operated through agglomeration economies associated with increases in urbanization.

It must be said at the outset that treating intercontinental trade as exogenous is a maintained hypothesis here, as are the remaining exclusion restrictions that make up the Allen’s model; see the appendix to Costa et al. (2015) for a full listing.

By using the real wage instead of GDP per capita, I am also biasing the results against finding an economically and statistically significant effect of intercontinental trade on GDP for two reasons: First, distributional issues suggest that if many of the gains from trade stayed concentrated in the hands of the merchant class (or were in the form of capital returns that did not “trickle down” to wages), then the real wage index will be missing those effects; second, since the nominal wage underlying the construction of the real wage index is the day wage, if people worked more days stimulated by the fruits of trade—as suggested by de Vries (2008) and Hersh and Voth (2009)—then, it will have been the case that the full effect of trade on GDP per capita will have been underestimated by using the real wage as a proxy. See some further discussion in Costa et al. (2015). Finally, although the same type of problem would be present if using GDP, the fact is that by using the Strasbourg basket (with local adjustments) corresponding to 1745–1754 for the calculation of real wages, I likely underestimate the amount of early modern growth and welfare gains since, unlike what would be strongly expected from microeconomic theory and evidence, agents are implicitly assumed not to respond to changes in relative prices. It should also be said, however, that for some of these countries (England and The Netherlands not included), the construction method for GDP is not independent from real wage data (though researchers have at times tried to make adjustments on the number of days worked).

For instance, Denmark and Sweden also engaged in intercontinental trade but the required data for these countries are not available.

I focus on reporting and interpreting the results for the real wage and on the urbanization rate. The results for the other two endogenous variables, the share of labor in proto-industry and the agricultural total factor productivity, are available upon request.

The point of using this estimator is as follows. Since unobserved country-specific idiosyncrasies in the error term (e.g., the micro details about how the empires or merchant networks of different countries were run) could be leading the pooled estimation methods to inconsistent parameter estimates, it may be possible to improve on the precision and credibility of the estimates by taking advantage of the panel data structure of the data. However, because lagged urbanization appears as an independent variable in some of the equations, the standard fixed effects estimator should not be used (Nickell 1981). One possibility would be to drop this variable, but since persistence plays a key role in the story, it is important to keep it. This problem can be solved using a dynamic panel data estimator: this way I allow for both persistence and (time-invariant) country-specific fixed effects.

I also include an “IV robust F-statistic” row in each of the regression tables, which shows the instruments are not weak, even under the most modern criteria (Stock and Yogo 2005).

Notice that the fact that Allen’s estimates are confirmed using a more advanced and robust estimation technique and an extended dataset should not be any less interesting than if the new estimates were significantly different from his original ones. On this issue of avoiding “negative results bias,” see for instance Duflo et al. (2007).

Allen’s model of the early modern economy is not without disadvantages. The exclusion restrictions which identify the model, and hence make it estimable, are taken as maintained assumptions, which is unavoidable (I did not perform tests of over-identifying restrictions, since the current consensus among econometric theorists is that these tests cannot be used to test for instrument validity; see, for instance, Parente and Silva 2012). A different criticism could be that even after controlling for the series of variables included, there may be something unobservable about some of the particular countries that would be driving the results. However, I also consider a number of robustness adjustments and alternative estimation methods, in particular, those specifically designed for panel data and that account for fixed effects. Further, I address the possibility of—potentially time-variant—“unobservable” idiosyncratic effects in detail in the “Appendix.” In any case, the safest way to think about the results is that they are conditional on Allen’s model for the European early modern economy, the key identifying assumptions of which are maintained throughout the analysis.

Further results (not shown) suggest that if instead it had access to per capita levels of trade equivalent to those of Portugal, it would have arrested most of its decline, and in fact, it would have even grow a little from 1700 onwards.

I do not include Belgium in the table due to this country’s unusually large residual: the model’s prediction for the historical case, which can be compared with the data, is somewhat worse than for the other countries; see the “Appendix” for further details and a formal justification. I emphasize that by doing so, I am biasing the results against the thesis that intercontinental trade mattered, as the simulated effect for Belgium is even larger than that of Poland.

For a convenient summary of the differences and a variance decomposition exercise for the case of England, see Angeles (2008).

Despite stagnated or declining real wages, during the early modern period, there was per capita GDP growth in Britain (Broadberry et al 2015), Holland (van Zanden and van Leeuwen 2012), and Portugal (Palma and Reis 2014); for Spain, the evidence is more mixed (Álvarez-Nogal and Prados de la Escosura 2013), and in the case of North and Central Italy, most of the period is one of decline (Malanima 2011).

Two notes about Figs. 5 and 6 are in order. First, I do not show France since as discussed before its low level of per capita trade could only trivially lead to small effects. Instead, I show England in these graphs. Second, the scale in the vertical axis for The Netherlands in Fig. 6 and for England in both figures is extended.

Further results (not shown) suggest that for the countries that did not engage in intercontinental trade, having done so at the average level of the “big four” would have been able to cancel much of the real wage losses associated with their own post-1600 population growth.

On the issue of financial innovation, see Neal (1990).

In fact, even the methods I have used in this paper are likely to underestimate the complete beneficial effects of the intercontinental trade because with it also came new technologies, products, and ideas, which contributed to pan-European growth and urbanization (see, for instance, Nunn and Qian 2011). Since all the countries in the sample used here are in Europe, any European-wide spillover effects indirectly caused by the maintenance of empires and merchant networks by some of the countries will be, by definition, absent, since the countries treated as “controls” would have been also been affected, and hence “contaminated.” Under the assumption—which certainly holds in-sample—that the empires had a positive effect on incomes, the existence of such an effect suggests that empires would have had an even stronger effect than that estimated. Additionally, the discovery of the New World may have also contributed to “opening the people’s minds,” hence contributing to faster subsequent scientific and technical change.

By lumping the value of precious metals together with other types of commodities, and by considering institutions as exogenous, this analysis also does not allow for the possibility of Dutch disease or institutional resource curse.

Conversely, one additional possibility which has not been considered here is that the countries that engaged in precious metal-intensive extraction operations, namely Spain and Portugal (the latter mainly the eighteenth century), may have suffered Dutch disease or institutional resource curse as a consequence.

A promising possibility in cases such as Poland, Italy, or Germany seems to be the coordination problems due to the absence of a centralized state.

What is certain is that the intensity of per capita engagement with intercontinental trade was strongly correlated with the “maritime culture” of the country, proxied by either the size of the coast in per capita terms or the proportion of land area within 100 km of the seacoast (as in Gallup et al. 1999). A stronger “maritime culture” would have favored the control of the seas (Blanning 2007, p. 646). This is not to say that other factors such as fiscal-military capacity did not matter as much or even more—indeed, I believe they did, especially for the later periods. However, these are less credibly exogenous and may have interacted with the former. Their analysis is beyond the scope of this paper.

For each country and each benchmark year, it is possible to calculate the residual, defined as the difference between the simulated and the historical wage (the simulated wage is simply the model’s prediction for the real wage under the observed values for the exogenous variables).

Absolute values were used for each benchmark period in the interest of values of opposing signs at different times not cancelling up.

As with the data of Fig. 1 from the main text, the value of (inflation-adjusted) intercontinental trade used here for The Netherlands and France is those of 1780 (The Netherlands), and 1788 (France), respectively, the last year of “normal” trade volumes; using zero instead leads to very similar results since only the terminal real wage—that of 1800—is affected.

References

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson J (2005) The rise of Europe: Atlantic trade, institutional change and economic growth. Am Econ Rev 95:546–579

Allen RC (2001) The great divergence in European wages and prices from the Middle Ages to the First World War. Explor Econ Hist 38:411–447

Allen RC (2003) Progress and poverty in early modern Europe. Econ Hist Rev 56:403–443

Allen RC (2009) The British industrial revolution in global perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Álvarez-Nogal C, Prados de la Escosura L (2013) The rise and fall of Spain (1270–1850). Econ Hist Rev 66(1):1–37

Angeles L (2008) GDP per capita or real wages? Making sense of conflicting views on pre-industrial Europe. Explor Econ Hist 45(2):147–163

Arellano M (2004) Panel data econometrics. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Blanning T (2007) The pursuit of glory. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bond S, Leblebicioglu A, Schiantarelli F (2010) Capital accumulation and growth: a new look at the empirical evidence. J Appl Econom 25(7):1073–1099

Braudel F (1980) Civilisation, Économie et Capitalisme. XV–XVIII Siècles. vol. 3. Le Temps du Monde. Armand Colin, Paris

Broadberry S, Gupta B (2006) The early modern great divergence: wages, prices and economic development in Europe and Asia, 1500–1800. Econ Hist Rev 59(1):2–31

Broadberry S, Campbell B, Klein A, Overton M, van Leeuwen B (2015) British economic growth, 1270–1870: an output-based approach. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Clark G (2005) The condition of the working class in England, 1209–2004. J Polit Econ 113(6):1307–1340

Clark G (2007) A farewell to alms: a brief economic history of the world. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Costa LF, Palma N, Reis J (2015) The great escape? The contribution of the empire to Portugal’s economic growth, 1500–1800. Eur Rev Econ Hist 19(1):1–22

de Vries J (2008) The industrious revolution: consumer behavior and the household economy, 1650 to the present. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Duflo E, Glennerster R, Kremer M (2007) Using randomization in development economics research: a toolkit. Handb Dev Econ 4:3895–3962

Findlay R, O’Rourke KH (2007) Power and plenty: trade, war and the world economy in the second millennium. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Frank AG (1978) World accumulation. Monthly Review Press, New York

Gallup JL, Sachs JD, Mellinger AD (1999) Geography and economic development. Int Reg Sci Rev 22(2):179–232

Goldstone JA (2002) Efflorescences and economic growth in world history: rethinking the “Rise of the West” and the Industrial Revolution. J World Hist 13(2):323–389

Hersh J, Voth H-J (2009) Sweet diversity: colonial goods and the rise of European living standards after 1492. SSRN eLibrary

Jones E (1988) Growth recurring: economic change in world history. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Harbor

Krugman P (1991) Increasing returns and economic geography. J Polit Econ 99:484–499

Lains P (1991) Foi a perda do império brasileiro um momento crucial do sub-desenvolvimento português?—II. Penélope 5:151–163

Malanima P (2011) The long decline of a leading economy: GDP in central and northern Italy, 1300–1913. Eur Rev Econ Hist 15(02):169

Marx K (1990/1867) Capital: critique of political economy, vol 1. Penguin Classics

Mokyr J (1985) The industrial revolution and the new economic history. In: Mokyr J (ed) The economics of the industrial revolution. Westview Press, Oxford

Mokyr J (2009) The enlightened economy: Britain and the industrial revolution, 1700–1850. Penguin, London

Mokyr J, Voth H-J (2010) Understanding growth in Europe, 1700–1870: theory and evidence. In: Broadberry S, O’Rourke K (eds) The Cambridge economic history of Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Myint H (1977) Adam Smith’s theory of international trade in the perspective of international development. Economica 44:231–248

Neal L (1990) The rise of financial capitalism: international capital markets in the age of reason. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York

Nickell S (1981) Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica 49:1417–1426

Nunn N, Qian N (2011) The potato’s contribution to population and urbanization: evidence from a historical experiment. Quart J Econ 126:593–650

O’Brien PK, Engerman SL (1991) Exports and the growth of the British economy from the glorious revolution to the peace of Amiens. In: Solow B (ed) Slavery and the rise of the Atlantic system, pp 177–209

O’Brien PK, Prados de la Escosura L (1998) (eds) The costs and benefits of European imperialism from the conquest of Ceuta to the treaty of Lusaka, 1974. Revista de Historia Económica (special issue) vol 16. pp 29–89

O’Brien P (1982) European economic development: the contribution of the periphery. Econ Hist Rev 35(1):1–18

O’Brien P (2006) The Hanoverian state and defeat of the continental system. In: Findlay R, Henrikson RGH, Lindgren H, Lundahl M (eds) Eli Heckscher, international trade, and economic history. The MIT Press, Boston, pp 373–408

Palma N, Reis J (2014) Portuguese demography and economic growth, 1500–1850 (unpublished manuscript)

Parente P, Silva JMC (2012) A cautionary note on tests of overidentifying restrictions. Econ Lett 115:314–317

Pedreira J (1994) Estrutura Industrial e Mercado Colonial: Portugal e Brasil (1780–1830). Difel, Lisboa

Pfister U (2009) German economic growth, 1500–1850. Historisches Seminar, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster

Pomeranz K (2000) The great divergence: China, Europe, and the making of the modern world economy. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Prados de la Escosura L (1988) De Império a Nación. Crecimiento y Atraso Económico en España (1780–1930). Alianza, Madrid

Prados de la Escosura L (1993) La pérdida del imperio y sus consequencias económicas en España. In: Prados de la Escosura L, Amaral S (eds) La Independencia Americana: Consequencias Económicas. Alianza Editorial, Madrid, pp 253–300

Reis J (2013) The economic growth of Portugal during the imperial era, 1500–1850: Is there an Iberian model? The Laureano Figuerola Lecture for 2013, Fundacion Areces, Madrid

Romer P (1993) Idea gaps and object gaps in economic development. J Monet Econ 32(3):543–573

Solow RM (1957) Technical change and the aggregate production function. Rev Econ Stat 39(3):312–320

Stock JH, Yogo M (2005) Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In: Stock JH, Andrews DWK (eds) Identification and inference for econometric models: essays in honour of Thomas J. Rothenberg. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge ch. 5

Thomas R (1968) The sugar colonies of the old empire: profit or loss for Great Britain? Econ Hist Rev 21:30–45

Thomas RP, McCloskey DN (1981) Overseas trade and empire 1700–1800. In: Floud R, McCloskey DN (eds) The economic history of Britain since 1700, vol 1, 2. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 87–102

van Zanden JL, van Leeuwen B (2012) Persistent but not consistent: the growth of national income in Holland, 1347–1807. Explor Econ Hist 49:119–130

Voth H-J (2001) Time and work in England, 1750–1830. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Wallerstein I (1974) The capitalist world-economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Wallerstein I (1980) The modern world-system II: mercantilism and the consolidation of the European world-economy, 1600–1750. Academic Press, New York

Williams E (1994) Capitalism and slavery. University of North Carolina Press, Chapell Hill, NC (First edition, 1944)

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Leonor F. Costa, Rui Pedro Esteves, Chris Minns, Maxine Montaigne, Alain Naef, Patrick O’Brien, Jaime Reis, and especially Leandro Prados de la Escosura and Alejandra Irigoin, for comments or discussions. I also acknowledge the contribution of two anonymous referees. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

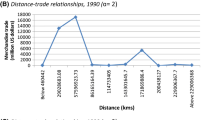

In this appendix, I provide some further discussion about a technical matter related to the model and its simulations. In particular, I discuss the difference between the model’s prediction for the historical situation in a given country at a given period, versus the observed values (the residual).Footnote 30 It is possible to calculate the average of the absolute number of the five residuals for each country.Footnote 31 I now show that—with the possible exception of Belgium, due to its exceptionally high initial levels of urbanization—there are no systematic biases to the (absolute value of the average) residual for any given country (Fig. 8).Footnote 32 This suggests that the fit for all countries is roughly similar and is suggestive that for any particular country the results are not being driven by unobserved specificities.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Palma, N. Sailing away from Malthus: intercontinental trade and European economic growth, 1500–1800. Cliometrica 10, 129–149 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-015-0126-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11698-015-0126-1