Abstract

Background

In 2015, The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended screening for prediabetes and undiagnosed diabetes (collectively called dysglycemia) among adults aged 40–70 years with overweight or obesity. The recommendation suggests that clinicians consider screening earlier in people who have other diabetes risk factors.

Objective

To compare the performance of limited and expanded screening criteria recommended by the USPSTF for detecting dysglycemia among US adults.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of survey and laboratory data collected from nationally representative samples of the civilian, noninstitutionalized US adult population.

Participants

A total of 3643 adults without diagnosed diabetes who underwent measurement of hemoglobin A1c (A1c), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), and 2-h plasma glucose (2-h PG).

Main Measures

Screening eligibility according to the limited criteria was based on age 40 to 70 years old and overweight/obesity. Screening eligibility according to the expanded criteria was determined by meeting the limited criteria or having ≥ 1 of the following risk factors: family history of diabetes, history of gestational diabetes or polycystic ovarian syndrome, and non-white race/ethnicity. Dysglycemia was defined by A1c ≥ 5.7%, FPG ≥ 100 mg/dL, and/or 2-h PG ≥ 140 mg/dL.

Key results

Among the US adult population without diagnosed diabetes, 49.7% had dysglycemia. Screening based on the limited criteria demonstrated a sensitivity of 47.3% (95% CI, 44.7–50.0%) and specificity of 71.4% (95% CI, 67.3–75.2%). The expanded criteria yielded higher sensitivity [76.8% (95% CI, 73.5–79.8%)] and lower specificity [33.8% (95% CI, 30.1–37.7%)]. Point estimates for the sensitivity of the limited criteria were lower in all minority groups and significantly different for Asians compared to non-Hispanic whites [29.9% (95% CI, 23.4–37.2%) vs. 49.8% (95% CI, 45.9–53.7%); P < .001].

Conclusions

Diabetes screening that follows the limited USPSTF criteria will identify approximately half of US adults with dysglycemia. Screening other high-risk subgroups defined in the USPSTF recommendation would improve detection of dysglycemia and may reduce associated racial/ethnic disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes and prediabetes (collectively called dysglycemia) affect approximately half of American adults, with higher prevalence estimates and greater complication rates among racial/ethnic minorities than whites.1, 2 In December 2015, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published a recommendation to screen for dysglycemia among asymptomatic adults who are 40–70 years old and overweight or obese.3 The recommendation suggests that clinicians consider screening earlier in people who have one or more of the following diabetes risk factors: family history of diabetes, history of gestational diabetes or polycystic ovarian syndrome among women, and non-white race/ethnicity.3 Under the Affordable Care Act, health insurance plans must cover services recommended by the USPSTF without cost sharing.4 However, it is unclear whether insurance coverage for dysglycemia screening will be based on age and weight alone, or the larger set of risk factors also included in the recommendation.

The goal of screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes is to promote earlier identification and therefore earlier or more intensive treatments to prevent negative health outcomes associated with these conditions.5 A large body of research has established the effectiveness of behavioral interventions and pharmacotherapy for treating diabetes and preventing its complications.6 Major clinical trials have also demonstrated that intensive lifestyle programs and some medications can prevent or delay diabetes among adults with prediabetes.7,8,–9

Our primary objective was to compare the performance of the following dysglycemia screening criteria outlined in the 2015 USPSTF recommendation: limited (age 40 to 70 years old and overweight/obese) vs. expanded (meeting the limited criteria or ≥ 1 of the following risk factors, regardless of age: family history of diabetes, history of gestational diabetes or polycystic ovarian syndrome, and non-white race/ethnicity). We examined these screening criteria in a nationally representative sample of US adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES). We also sought to estimate the performance of the limited criteria separately within race/ethnicity subgroups, given evidence that Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks develop dysglycemia at younger ages than whites, and Asians do so at lower body weights.10, 11

METHODS

Data Source and Participants

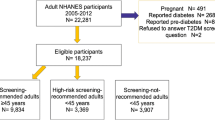

The data source was the 2011–2014 NHANES. Using a complex, multistage probability sample design, NHANES presents nationally representative descriptive statistics of the health status of the non-institutionalized US civilian population. The protocols for collecting interview and biologic specimen data in NHANES, including response rates, are described in-depth elsewhere.12 The study participants were adults aged ≥ 20 years who underwent fasting blood collection and a 2-h oral glucose tolerance test. We excluded those reporting a previous diagnosis of diabetes (n = 578) and pregnant women (n = 1). Participants missing data for physician-diagnosed diabetes, body mass index (BMI), or glycemic measures were also excluded (n = 22). The final analytic sample included 3643 participants.

Key Variables

Screening eligibility based on the limited criteria was determined using NHANES variables for age and objectively measured BMI. Participants aged 40 to 70 years with overweight/obesity were considered eligible for screening according to the limited criteria. Screening eligibility based on the expanded criteria was determined using NHANES variables for family history of diabetes, history of gestational diabetes, history of polycystic ovarian syndrome, and race/ethnicity. Racial and ethnic minority groups sampled in NHANES are non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics/Latinos, and non-Hispanic Asians, who comprise those with origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent.13 Individuals meeting the limited criteria or at least one of the other diabetes risk factors listed above were considered eligible for screening based on the expanded criteria. The main outcome was dysglycemia, defined by one of the following glycemic tests performed at a single time point: 2-h postload glucose (2-h PG) ≥ 140 mg/dL, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 100 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1c (A1c) ≥ 5.7%.6 Other diabetes risk factors were analyzed as covariates: sex, blood pressure, waist circumference, lipid levels, physical inactivity, educational attainment, income, and insurance status.6, 14,15,–16

Statistical Analysis

We used summary statistics to describe the characteristics of adults with dysglycemia overall (n = 1990) and by their eligibility for screening according to the limited and expanded criteria. In the full sample of eligible adults without diagnosed diabetes (N = 3643), we examined the following performance characteristics of the limited and expanded screening criteria: sensitivity (proportion of adults with dysglycemia who meet the criteria), specificity (proportion of those without dysglycemia who do not), positive predictive value (PPV, proportion of adults meeting the criteria who have dysglycemia), and negative predictive value (NPV, proportion of those not meeting the criteria who are free of dysglycemia). For both sets of criteria, test performance was determined separately by weight status (normal weight, overweight, and obese). Test performance of the limited criteria was stratified by race/ethnicity, and the significance of differences between groups was examined using Chi-square tests. A P value of < .05 was considered significant for all statistical testing.

We conducted the following sensitivity analyses. The same analyses described above were repeated among those who completed only FPG and HbA1c measurement, without OGTT (n = 1834). As recommended by some experts, an overweight/obese definition of BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 for Asians was also used to determine screening eligibility and the limited criteria’s performance in this group.17 We used SAS version 9.3 (Cary, NC) and SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11 (Research Triangle Park, NC) to conduct statistical analysis, accounting for NHANES’ complex survey design. The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board approved NHANES. All participants gave informed consent.

RESULTS

Overall, 49.7% of the sample population without diagnosed diabetes had dysglycemia, with the following estimated prevalence within each racial/ethnic group: non-Hispanic white (48.6%), black (54.0%), Hispanic/Latino (50.9%), and Asian (51.2%). Extrapolating the overall prevalence estimate to the Census resident population of adults without diagnosed diabetes yields a total of 105.1 million Americans with dysglycemia. Table 1 presents the characteristics of all adults with dysglycemia, and Tables 2 and 3 display their characteristics according to screening eligibility and ineligibility, respectively. The two sets of screening criteria identified adults with similar cardiometabolic profiles, including mean glycemic values that were comparable between the eligible groups (Table 2). Relative to eligible adults, those who were ineligible by both sets of criteria had lower mean values for all cardiometabolic markers except HDL cholesterol (Table 3).

By definition, the limited screening criteria identified only individuals with dysglycemia whose age and BMI were within their respective target ranges. Similarly, the expanded criteria captured all adults with dysglycemia who were racial/ethnic minorities or had other clinical risk factors comprising these criteria. In addition, greater proportions of the following subgroups with dysglycemia were eligible for screening based on the expanded criteria vs. the limited criteria: women, educational attainment less than high school, household income below the federal poverty level, and uninsured.

Table 4 presents the performance of the USPSTF’s limited and expanded screening criteria among all US adults without diagnosed diabetes. The performance characteristics of the limited criteria were as follows: sensitivity 47.3% (95% CI, 44.7–50.0%); specificity 71.4% (95% CI, 67.3–75.2%); PPV 62.0% (95% CI, 57.8–66.1%); and NPV 57.8% (95% CI, 54.9–60.8%). The estimated sensitivity of the limited criteria was lower within each racial/ethnic subgroup compared to non-Hispanic whites, and this difference was statistically significant among Asians. Using an overweight/obesity BMI cutoff of ≥ 23 kg/m2 in Asians,17 the performance of the limited criteria was comparable with other racial/ethnic minority groups, and the difference in sensitivity relative to whites was no longer statistically significant. The specificity and PPV of the limited criteria were significantly higher among all racial/ethnic minority groups (Table 4). Overall, the expanded screening criteria demonstrated the following performance characteristics: sensitivity 76.8% (95% CI, 73.5–79.8%); specificity 33.8% (95% CI, 30.1–37.7%); PPV 53.4% (95% CI, 50.2–56.6%); and NPV 59.6% (95% CI, 55.6–63.4%). The expanded criteria exhibited greater sensitivity and lower specificity with increasing BMI (Table 5). For both the limited and expanded criteria, Table 6 presents the estimated number of adults (per 1000 population) by their eligibility for screening and dysglycemia status. In sensitivity analyses defining dysglycemia based on FPG and A1c alone, we found no substantive differences in the screening criteria’s performance compared to the primary findings.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study investigating the performance of the full 2015 USPSTF dysglycemia screening recommendation in a nationally representative sample of US adults without diagnosed diabetes. Our findings highlight clinically significant differences in sensitivity and specificity between the USPSTF’s main screening recommendation (i.e., limited criteria) and the additional risk factors included in the same report (i.e., expanded criteria). Dysglycemia screening based on the expanded criteria demonstrated higher sensitivity and lower specificity than age and weight alone. In practice, this means that fewer dysglycemia cases will be missed by the expanded criteria; however, more adults without dysglycemia will be tested, only to find that the result is normal. Point estimates for the sensitivity of the limited criteria were lower in all minority groups. This difference was statistically significant for Asians using the standard BMI definition of overweight/obesity, but did not remain significant when using a lower BMI threshold. The specificity of the limited criteria was significantly higher in all racial/ethnic minority groups relative to whites and was highest among Asians.

When making its recommendations, the USPSTF assigns a letter grade to each preventive service based on the certainty of evidence supporting it and the balance of associated benefits and harms.18 The limited criteria in the current screening recommendation received a grade B, indicating moderate to high certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial.19 Because the Affordable Care Act mandates that insurers cover the full cost of services that receive a grade B recommendation,20 there is current debate about whether payers should also fully reimburse dysglycemia screening for patients who meet the expanded criteria alone.21 In this context, our analysis provides the first performance estimates for these two sets of screening criteria endorsed by USPSTF, thereby enabling appraisal of the trade-offs associated with their use.

Prior research has found that screening for dysglycemia based on a single diabetes risk factor yields lower sensitivity and higher specificity than using a greater number of risk factors.22, 23 The USPSTF’s prior 2008 recommendation to screen adults with hypertension alone demonstrated sensitivity of 44.4% and specificity of 74.8%.24 By contrast, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends screening all adults who are overweight/obese with other diabetes risk factors including those currently listed in the USPSTF’s expanded criteria, in addition to physical inactivity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or cardiovascular disease.6 This ADA screening recommendation demonstrated similar performance to the USPSTF’s expanded criteria.25 Collectively, these data demonstrate that using broad screening criteria maximizes detection of dysglycemia (i.e., sensitivity), whereas following narrow criteria maximizes efficiency by testing fewer eligible adults without dysglycemia (i.e., specificity).

To our knowledge, only one previous study has investigated the performance of the 2015 USPSTF screening recommendation. This analysis of the limited criteria used clinical data from community health centers, reporting a sensitivity of 45.0% and a specificity of 71.9%.26 Despite studying a clinical cohort of adult primary care patients in the Midwest and Southwest, this paper’s estimates of sensitivity and specificity were remarkably similar to those found here in a nationally representative population. No studies have yet tested the performance of the expanded criteria endorsed by USPSTF in the same report.

Our current analysis found that the expanded criteria perform more favorably than limited criteria in certain population subgroups, which may accelerate evidence-based interventions to prevent or treat diabetes. There was a trend toward lower sensitivity of the limited screening criteria in all minority groups compared to whites, most prominently among Asians, who have an elevated risk of dysglycemia at normal body weight.27 Lower sensitivity of the limited criteria among racial/ethnic minorities was also reported in our previous analysis of community health center patients, which found higher rates of dysglycemia at younger ages and lower weights among these groups.26 Because the USPSTF’s expanded criteria include non-white race/ethnicity, all minorities would routinely receive screening under this approach and disparities in diagnosing dysglycemia among these groups may be reduced.

There were other key differences in the characteristics of adults who were eligible for screening according to the USPSTF’s limited vs. expanded criteria, which may present opportunities to improve dysglycemia detection in other vulnerable groups. Individuals with low socioeconomic status are less likely to be screened following the limited criteria, as evidenced by smaller proportions of adults with low educational attainment and household incomes who were identified. This finding is concerning given that socioeconomic disadvantage is associated with elevated diabetes risk.16 Because the limited criteria do not include gestational diabetes and polycystic ovarian syndrome, women with dysglycemia are also less likely to be identified. This is significant given the higher lifetime risk of diabetes among women than men.14 Adults who have dysglycemia at a normal weight constitute 23.9% of cases, who would not be screened following the limited criteria. One quarter of adults with dysglycemia are younger than 40 years old and are also not captured by the limited criteria. Failing to screen young adults could increase the already long period of exposure for developing complications associated with prediabetes and diabetes. Adults over 70 represent a high-risk group that would also not be screened according to the limited criteria. However, their shorter life expectancy and greater risk associated with diabetes treatment may change the balance of potential benefits and harms associated with screening this group.28 Adopting the expanded criteria would result in screening a substantially higher proportion of these groups that are missed by the limited criteria.

The comparative performance of dysglycemia screening criteria has implications for clinical practice. Targeted screening approaches with high sensitivity and low specificity may be most appropriate to identify patients who have conditions requiring urgent diagnosis and treatment, when screening tests are inexpensive, or the harms of false-positive screening results are low. By contrast, screening criteria with low sensitivity and high specificity may be preferred when diagnosis or treatment is less urgent, screening tests and/or treatments are expensive, or the harms of a false-positive screening result are significant. Adopting the expanded USPSTF criteria will result in more glycemic tests conducted, yielding both a greater number of dysglycemia cases identified and more false positive results, which may provide an opportunity for clinicians to reinforce healthy lifestyle behaviors. While this approach will have higher total costs due to more testing, many adults are already undergoing regular lipid screening according to age-based recommendations. Following the limited USPSTF criteria will have lower associated costs due to less testing, at the expense of detecting fewer cases. However, it is possible that the net costs of adopting the expanded criteria may actually be lower than the limited criteria since interventions to prevent diabetes have reduced future medical expenditures.29 Glycemic testing completed during routine medical care, often called opportunistic screening, represents another approach to identify adults with dysglycemia. However, the utility of opportunistic screening is limited by a predominance of random glucose tests,26, 30 which are not recommended for this purpose.3, 6

Another important clinical consideration is the potential benefit that patients may derive from screen-detected dysglycemia. Large randomized trials have shown that treatment for diabetes reduces microvascular and macrovascular complications31, 32, while economic studies have demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of diabetes treatment.33 The benefit of intensive lifestyle interventions and some medications to prevent diabetes is also clearly established,7,8,–9 with studies suggesting that these interventions are most efficacious and cost-effective among the highest-risk prediabetic adults.34, 35 Follow-up studies demonstrate that lifestyle programs produce durable reductions in diabetes incidence36, 37 and may reduce microvascular complications,38, 39 cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality.40 However, applying evidence from landmark diabetes prevention trials to inform screening practices is complicated by the broader definition of prediabetes used by USPSTF compared to these earlier studies. Further, participants in these trials were overweight or obese, leaving the benefit of interventions to prevent diabetes less certain in adults who have a normal body weight. Future research should study diabetes prevention efforts in lean adults.

Our study is timely given its examination of the USPSTF’s most recent dysglycemia screening recommendation. Strengths of using nationally representative data from NHANES include reliable estimates of health indicators for Asians beginning in 2011. Analyzing data since 2011 resulted in a smaller sample and less precise estimates than pooling larger numbers of participants from previous years. The NHANES definition of Asian race does not include Pacific Islanders, in whom diabetes risk is associated with obesity.41 Had this group been included, the sensitivity of the limited criteria among Asian Americans would likely be higher and the specificity lower than those reported here. Due to the cross-sectional design of NHANES, we could not confirm the diagnosis of dysglycemia based on repeat testing. This may have overestimated the prevalence of undiagnosed dysglycemia due to some cases that would not have been confirmed by a second abnormal result. One recent study estimated that undiagnosed diabetes that is confirmed by a second glycemic test result constituted 11% of total cases, compared to one-quarter or one-third of cases based on a single abnormal result.42 To the extent that dysglycemia cases in the current study were identified by fasting glucose or A1c, this problem may not have had a large impact on our findings because of lower intraindividual variation associated with these tests (coefficient of variation 5.7 and < 1%, respectively) than 2-h postload glucose (coefficient of variation 16.7%).43 While all three glycemic tests were performed in NHANES and analyzed here, this is not often the case in routine clinical practice.26, 30 Finally, we did not compare the current USPSTF screening criteria to those recommended by the ADA or other expert groups, which may be a direction for future research.

In conclusion, targeted diabetes screening that follows only the age- and weight-based criteria recommended by USPSTF will identify approximately half of US adults with dysglycemia. Following the recommendation’s expanded criteria that include other diabetes risk factors would improve detection of dysglycemia and provide earlier opportunities to intervene both across the population and in several high-risk groups, including racial/ethnic minorities. Future research might examine use of the USPSTF screening criteria in practice and study their impact on dysglycemia diagnosis, treatment, and costs in diverse population subgroups.

REFERENCES

Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and Trends in Diabetes Among Adults in the United States, 1988-2012. JAMA. 2015 Sep 8;314(10):1021–9.

Lanting LC, Joung IM, Mackenbach JP, Lamberts SW, Bootsma AH. Ethnic differences in mortality, end-stage complications, and quality of care among diabetic patients: a review. Diabetes Care. 2005 Sep;28(9):2280–8.

Siu AL. Screening for Abnormal Blood Glucose and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Dec 1;163(11):861–8.

Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Golub RM. JAMA Welcomes the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016 Jan 26;315(4):351–2.

Selph S, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Patel H, Chou R. Screening for Abnormal Glucose and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review to Update the 2008 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2017. Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40(Suppl 1):S1-S135.

Knowler W, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler S, Hamman RF, Lachin J, Walker E, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403.

Pan XR, Li G, Hu YH, Wang JX, Yang WY, An ZX, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance: the Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(4):537–44.

Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hämäläinen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(18):1343–50.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011.

Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Saydah S, Imperatore G, Linder B, Divers J, et al. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. JAMA. 2014 May 7;311(17):1778–86.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Atlanta, GA: CDC/National Center for Health Statistics, 2016; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm [accessed February 27, 2018].

Johnson CL, Dohrmann SM, Burt VL, Mohadjer LK. National health and nutrition examination survey: sample design, 2011-2014. Vital Health Statistics. 2014 Mar(162):1–33.

Narayan KMV, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1884–90.

Bray GA, Jablonski KA, Fujimoto WY, Barrett-Connor E, Haffner S, Hanson RL, et al. Relation of central adiposity and body mass index to the development of diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1212–8.

Agardh E, Allebeck P, Hallqvist J, Moradi T, Sidorchuk A. Type 2 diabetes incidence and socio-economic position: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2011 Jun;40(3):804–18.

World Health Organization. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004 Jan 10;363(9403):157–63.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2014: Appendix A: How the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Grades Its Recommendations. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2014; Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/guide/appendix-a.html [accessed February 27, 2018].

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Grade Definitions, 2016; Available from: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/grade-definitions [accessed February 27, 2018].

Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman D. Evidence-Based Clinical Prevention in the Era of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: The Role of the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2015 Nov 17;314(19):2021–2.

Diabetes Advocacy Alliance. Coalition Letter: Request to release FAQ regarding coverage of preventive services under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, 2016; Available from: https://www.aace.com/files/views/072616-tridpts-re-diabetes-screening.pdf [accessed February 27, 2018].

Dall TM, Narayan KM, Gillespie KB, Gallo PD, Blanchard TD, Solcan M, et al. Detecting type 2 diabetes and prediabetes among asymptomatic adults in the United States: modeling American Diabetes Association versus US Preventive Services Task Force diabetes screening guidelines. Popul Health Metr. 2014;12:1–14.

Chung S, Azar KM, Baek M, Lauderdale DS, Palaniappan LP. Reconsidering the age thresholds for type II diabetes screening in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2014 Oct;47(4):375–81.

Casagrande SS, Cowie CC, Fradkin JE. Utility of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force criteria for diabetes screening. Am J Prev Med. 2013 Aug;45(2):167–74.

Bullard KM, Ali MK, Imperatore G, Geiss LS, Saydah SH, Albu JB, et al. Receipt of Glucose Testing and Performance of Two US Diabetes Screening Guidelines, 2007-2012. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0125249.

O'Brien MJ, Lee JY, Carnethon MR, Ackermann RT, Vargas MC, Hamilton A, et al. Detecting Dysglycemia Using the 2015 United States Preventive Services Task Force Screening Criteria: A Cohort Analysis of Community Health Center Patients. PLoS Med. 2016 Jul;13(7):e1002074.

Hsu WC, Araneta MR, Kanaya AM, Chiang JL, Fujimoto W. BMI cut points to identify at-risk Asian Americans for type 2 diabetes screening. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(1):150–8.

Lipska KJ, Krumholz H, Soones T, Lee SJ. Polypharmacy in the Aging Patient: A Review of Glycemic Control in Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1034–45.

Community Preventive Services Task Force. Diabetes Prevention and Control: Combined Diet & Physical Activity Programs– Economic Evidence Tables. Atlanta, GA 2016; Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/SETcombineddietandpa-econ.pdf [accessed February 27, 2018].

Ealovega MW, Tabaei BP, Brandle M, Burke R, Herman WH. Opportunistic screening for diabetes in routine clinical practice. Diabetes Care. 2004 Jan;27(1):9–12.

Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005 Dec 22;353(25):2643–53.

DCCT-EDIC Writing Group. Effect of intensive therapy on the microvascular complications of type 1 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2002 May 15;287(19):2563–9.

Wagner EH, Sandhu N, Newton KM, McCulloch DK, Ramsey SD, Grothaus LC. Effect of improved glycemic control on health care costs and utilization. JAMA. 2001;285(2):182–9.

Sussman JB, Kent DM, Nelson JP, Hayward RA. Improving diabetes prevention with benefit based tailored treatment: risk based reanalysis of Diabetes Prevention Program. BMJ. 2015;350:h454.

Zhuo X, Zhang P, Kahn HS, Gregg EW. Cost-Effectiveness of Alternative Thresholds of the Fasting Plasma Glucose Test to Identify the Target Population for Type 2 Diabetes Prevention in Adults Aged≥ 45 Years. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(12):3992–8.

Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, Gregg EW, Yang W, Gong Q, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371(9626):1783–9.

Knowler W, Fowler S, Hamman R, Christophi C, Hoffman H, Brenneman A, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1677.

Gong Q, Gregg EW, Wang J, An Y, Zhang P, Yang W, et al. Long-term effects of a randomised trial of a 6-year lifestyle intervention in impaired glucose tolerance on diabetes-related microvascular complications: the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Outcome Study. Diabetologia. 2011 Feb;54(2):300–7.

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015 Nov;3(11):866–75.

Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, An Y, Gong Q, Gregg EW, et al. Cardiovascular mortality, all-cause mortality, and diabetes incidence after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance in the Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 23-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(6):474–80.

Karter AJ, Schillinger D, Adams AS, Moffet HH, Liu J, Adler NE, et al. Elevated rates of diabetes in Pacific Islanders and Asian subgroups: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Diabetes Care. 2013 Mar;36(3):574–9.

Selvin E, Wang D, Lee AK, Bergenstal RM, Coresh J. Identifying Trends in Undiagnosed Diabetes in U.S. Adults by Using a Confirmatory Definition: A Cross-sectional Study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(11):769–76.

Sacks DB. A1C versus glucose testing: a comparison. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):518–23.

Acknowledgments

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The NIDDK and CDC Division of Diabetes Translation funded the diabetes component of the NHANES and have input into the design and conduct of the study, and the collection and management of the data with regard to diabetes-related data. Other than the study authors, the NIDDK and the CDC had no role in the design, analysis, and interpretation of the secondary analysis; preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The CDC reviewed and approved the manuscript before submission. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC or the NIDDK.

Funding

The study was supported by grants R21-DK112066, R01-HL093009, UL1-TR001422. There were no commercial sponsors of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M.B. had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. M.J.O., K.M.B., Y.Z., E.W.G., and R.T.A designed the study. All authors contributed to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data. M.J.O. drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Y.Z. and K.M.B. conducted the statistical analysis. K.M.B. provided administrative, technical, or material support and E.W.G. supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The National Center for Health Statistics Research Ethics Review Board approved NHANES. All participants gave informed consent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Brien, M.J., Bullard, K.M., Zhang, Y. et al. Performance of the 2015 US Preventive Services Task Force Screening Criteria for Prediabetes and Undiagnosed Diabetes. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 1100–1108 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4436-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4436-4