Abstract

Background

The increasing and specific use of home care services by frail, older people asks for the evaluation of the client-centeredness of these services. To our knowledge, no instrument that measures client-centeredness of home care from this group’s unique perspective exists. We therefore tested the factor structure, reliability, content validity and acceptability of the Client-centered Care Questionnaire (CCCQ), an existing instrument developed for general home care users, in a population of frail, older people in the Netherlands.

Methods

We used data from a 2-year clinical trial. Study population: frail, older people who received home care. Data were collected at baseline (n = 600) and 24-month measurements (n = 389); retest data (n = 67) were collected 7–14 days after the 24-month measurements. Analyses: We performed confirmatory factor analysis, investigated reliability and validity parameters and assessed acceptability.

Results

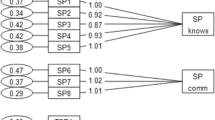

The factor analysis yielded a bifactor model with essential unidimensionality. Internal consistency was high (omega total .88). We found a test–retest reliability of total test scores of .81; the standard error of measurement was 2.61 (total score range 15–75) and the limits of agreement were −7.03 and 7.86. We rejected three out of four hypotheses for construct validity.

Conclusions

The CCCQ is sufficiently unidimensional to permit the use of total test scores. We found acceptable reliability values, but considered our results on construct validity inconclusive. Respondents found the CCCQ questions challenging to answer, which is indicative of a high degree of respondent burden. Future instruments that measure client-centeredness of home care from the frail, older client’s perspective should therefore be tailored to the specific circumstances of this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abdellah, F. G., Beland, I. L., Martin, A., & Matheney, R. V. (1960). Patient-centered approaches to nursing. New York, USA: Macmillan.

Abdellah, F. G. (1973). New directions in patient centered nursing: guidelines for systems of service education and research.New York, USA: Macmillan.

Gerteis, M., Edgman-Levitan, S., Daley, J., & Delbanco, T. L. (1993). Through the patient’s eyes: Understanding and promoting patient-centered care. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Leino, A. (1952). Planning patient-centered care. AJN The American Journal of Nursing, 52, 324–325.

Lutz, B. J., & Bowers, B. J. (2000). Patient-centered care: understanding its interpretation and implementation in health care. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 14, 165–183.

Mead, N., & Bower, P. (2000). Patient-centredness: A conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Social Science and Medicine, 51, 1087–1110.

Bechel, D. L., Myers, W. A., & Smith, D. G. (2000). Does patient-centered care pay off? Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement, 26, 400–409.

Stewart, M., Brown, J. B., Donner, A., McWhinney, I. R., Oates, J., Weston, W. W., et al. (2000). The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. Journal of Family Practice, 49, 796–804.

Epstein, R. M., Fiscella, K., Lesser, C. S., & Stange, K. C. (2010). Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Affairs, 29, 1489–1495.

Robinson, J. H., Callister, L. C., Berry, J. A., & Dearing, K. A. (2008). Patient-centered care and adherence: Definitions and applications to improve outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 20, 600–607.

Hobbs, J. L. (2009). A dimensional analysis of patient-centered care. Nursing Research, 58, 52–62.

Jayadevappa, R., & Chhatre, S. (2011). Patient centered care-A conceptual model and review of the state of the art. The Open Health Services and Policy Journal, 4, 15–25.

Eales, J., Keating, N., & Damsma, A. (2001). Seniors’ experiences of client-centred residential care. Ageing and society, 21, 279–296.

Law, M., Baptiste, S., & Mills, J. (1995). Client-centred practice: What does it mean and does it make a difference? Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62, 250–257.

Cott, C. A., Teare, G., McGilton, K. S., & Lineker, S. (2006). Reliability and construct validity of the client-centred rehabilitation questionnaire. Disability and Rehabilitation, 28, 1387–1397.

de Witte, L., Schoot, T., & Proot, I. (2006). Development of the client-centred care questionnaire. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56, 62–68.

Wiles, J. L., Leibing, A., Guberman, N., Reeve, J., & Allen, R. E. S. (2012). The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontologist, 52, 357–366.

Fried, L. P., Ferrucci, L., Darer, J., Williamson, J. D., & Anderson, G. (2004). Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: Implications for improved targeting and care. Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 59, 255–263.

Muntinga, M., Hoogendijk, E., van Leeuwen, K., van Hout, H., Twisk, J., van der Horst, H., et al. (2012). Implementing the chronic care model for frail older adults in the Netherlands: study protocol of ACT (frail older Adults: Care in Transition). BMC Geriatrics, 12, 19.

Schuurmans, H., Steverink, N., Lindenberg, S., Frieswijk, N., & Slaets, J. P. J. (2004). Old or frail: What tells us more? Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 59, M962–M965.

Raiche, M., Hebert, R., & Dubois, M. F. (2008). PRISMA-7: A case-finding tool to identify older adults with moderate to severe disabilities. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 47, 9–18.

De Vet, H., Terwee, C., Mokkink, L., & Knol, D. (2011). Measurement in medicine: A practical guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wirth, R. J., & Edwards, M. C. (2007). Item factor analysis: Current approaches and future directions. Psychological Methods, 12, 58–79.

Babyak, M. A., & Green, S. B. (2010). Confirmatory factor analysis: An introduction for psychosomatic medicine researchers. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72, 587–597.

Chen, F. F., Hayes, A., Carver, C. S., Laurenceau, J. P., & Zhang, Z. (2012). Modeling general and specific variance in multifaceted constructs: A comparison of the bifactor model to other approaches. Journal of Personality, 80, 219–251.

Chen, F. F., West, S. G., & Sousa, K. H. (2006). A comparison of bifactor and second-order models of quality of life. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 41, 189–225.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives, structural. Equation Modeling-A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55.

Ten Berge, J. M., & Socan, G. (2004). The greatest lower bound to the reliability of a test and the hypothesis of unidimensionality. Psychometrika, 69, 613–625.

Reise, S. P. (2012). The rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 47, 667–696.

Green, S. B., & Yang, Y. (2009). Reliability of summed item scores using structural equation modeling: An alternative to coefficient alpha. Psychometrika, 74, 155–167.

Reise, S. P., Morizot, J., & Hays, R. D. (2007). The role of the bifactor model in resolving dimensionality issues in health outcomes measures. Quality of Life Research, 16(Suppl 1), 19–31.

Reise, S. P., Bonifay, W. E., & Haviland, M. G. (2013). Scoring and modeling psychological measures in the presence of multidimensionality. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95, 129–140.

McGraw, K. O., & Wong, S. P. (1996). Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychological Methods, 1, 30–46.

Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (1986). Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet, 1, 307–310.

Jayasinghe, U. W., Proudfoot, J., Holton, C., Davies, G. P., Amoroso, C., Bubner, T., et al. (2008). Chronically ill Australians’ satisfaction with accessibility and patient-centredness. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 20, 105–114.

Watkins, M., & Beaujean, A. (2013). Bifactor structure of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Fourth Edition. Sch Psychol. Q.,.

Teresi, JA., Ocepek-Welikson, K., Ramirez, M., Eimicke JP., Silver, S., Van Haitsma, K., Lachs, MS., & Pillemer, KA. (2013). Development of an instrument to measure staff-reported resident-to-resident elder mistreatment (R-REM) using item response theory and other latent variable models. Gerontologist. doi:10.1093/geront/gnt001

Lai, J. S., Crane, P. K., & Cella, D. (2006). Factor analysis techniques for assessing sufficient unidimensionality of cancer related fatigue. Quality of Life Research, 15, 1179–1190.

Baker, D. W., Gazmararian, J. A., Sudano, J., & Patterson, M. (2000). The association between age and health literacy among elderly persons. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55, S368–S374.

McHorney, C. A. (1996). Measuring and monitoring general health status in elderly persons: Practical and methodological issues in using the SF-36 Health Survey. The Gerontologist, 36, 571–583.

Ulrich, C. M., Wallen, G. R., Feister, A., & Grady, C. (2005). Respondent burden in clinical research: when are we asking too much of subjects? IRB: Ethics and Human Research, 27, 17–20.

Acknowledgments

We owe many thanks to the research assistants (Daphne Stevens and Wencke de Jager) and the project interviewers who collected the data. In addition, we would like to acknowledge all organizations and professionals involved in ‘Ouderennnet VUmc en partners’ (www.ouderennet-vumc.nl) for their contribution to the development of the ACT-study. The ACT-study is funded by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw): Dutch National Care for the Elderly Program Grant Number 311080201.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

CCCQ-items. English translation adapted from de Witte L, Schoot T, Proot I. Development of the Client-Centered Care Questionnaire. J Adv Nurs 2006 Oct; 56(1):62–8.

A

-

1.

I can tell that the carers take my personal wishes into account

-

2.

I can tell that the carers really listen to me

-

3.

I can tell that the carers take into account what I tell them

-

4.

I get enough opportunity to say what kind of care I need

-

5.

I can tell that the carers respect my decision even though I disagree with them

-

6.

In my opinion the carers are clear about what care they are able and allowed to provide

-

7.

In my opinion the carers are sometimes too quick to say that something is not possible*

-

8.

I am given enough opportunity to use my own expertise and experience with respect to the care I need

-

9.

I am given enough opportunity to do what I am capable of doing myself

-

10.

I am given enough opportunity to help decide on the kind of care I receive

B

-

1.

I am given enough opportunity to help decide on how often I receive care

-

2.

I am given enough opportunity to help decide on how the care is given

-

3.

I have a say in deciding on when carers come to help me

-

4.

In my opinion, I am consulted sufficiently on who provides the care

-

5.

I’m given enough opportunity to arrange and organize the provided care myself

*reverse scored

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muntinga, M.E., Mokkink, L.B., Knol, D.L. et al. Measurement properties of the Client-centered Care Questionnaire (CCCQ): factor structure, reliability and validity of a questionnaire to assess self-reported client-centeredness of home care services in a population of frail, older people. Qual Life Res 23, 2063–2072 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0650-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0650-7