Abstract

Objective

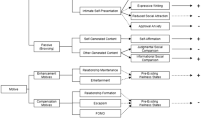

Motivated by the reorientation of gang membership into a life-course framework and concerns about distinct populations of juvenile and adult gang members, this study draws from the criminal career paradigm to examine the contours of gang membership and their variability in the life-course.

Methods

Based on nine annual waves of national panel data from the NLSY97, this study uses growth curve and group-based trajectory modeling to examine the dynamic and cumulative prevalence of gang membership, variability in the pathways into and out of gangs, and the correlates of these pathways from ages 10 to 23.

Results

The cumulative prevalence of gang membership was 8 %, while the dynamic age-graded prevalence of gang membership peaked at 3 % at age 15. Six distinct trajectories accounted for variability in the patterning of gang membership, including an adult onset trajectory. Gang membership in adulthood was an even mix of adolescence carryover and adult initiation. The typical gang career lasts 2 years or less, although much longer for an appreciable subset of respondents. Gender and racial/ethnic disproportionalities in gang membership increase in magnitude over the life-course.

Conclusions

Gang membership is strongly age-graded. The results of this study support a developmental research agenda to unpack the theoretical and empirical causes and consequences of gang membership across stages of the life-course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Both official and survey estimates involve self-report methodology to measure gang membership, although the former also includes additional filters. Barrows and Huff (2009) documented the criteria used by 10 states to document a gang member; self-identification was the only criterion used by all states and with the exception of Virginia, every state required at least two categories before someone can be defined as a gang member.

Esbensen and Huizinga (1993) reported four years of data on gang membership and values were extrapolated based on ages that applied to at least two of the DYS cohorts (youth born in 1972, 1974, 1976, and 1978).

Delinquent group participation was measured as follows: “During the past 12 months, were you part of a group or gang that did reprehensible acts?” (Lacourse et al. 2003, p. 186, emphasis added). The delinquent group component of this definition may contribute to such high rates of gang membership (e.g., 21 % at age 14 in Craig et al. (2002)).

The definition that the NLSY97 presents to respondents is more restrictive than the commonly used Eurogang definition—“a street gangs is any durable, street-oriented youth group whose involvement in illegal activity is part of its group identity” (Klein and Maxson 2006: 4). Individual-level gang research does not typically preface gang membership self-nomination questions with a definition of a gang, therefore it is unknown whether such a procedure unduly influences results. The NLSY97 is commonly used to study gang member behavior (e.g., Bellair and McNulty 2009; Bjerk 2009; Tapia 2011) and the findings from these studies are consistent with research from sites using potentially less restrictive definitions.

A measure of “ever” gang membership was presented to all respondents at Waves 1–5, although those who did not answer the measure of “current” gang membership were the universe for this question. There are some instances (~ 2 %) where respondents deny “current” gang membership, only report to “ever” gang membership and provide ages of onset and termination that overlap with Waves 2–5. Those who do not own up to gang membership until later waves are worth studying for conceptual and methodological reasons, including identity, gang embeddedness, criminal and noncriminal consequences, and the reliability and validity of self-nomination. There are defensible reasons for inclusivity, but the goal of the current study was to measure gang membership as close to the state as possible, therefore only Wave 1 “ever” gang membership was used to retrospectively capture onset and termination.

The concerns about GBTM (see Sampson and Laub 2005; Skardhamar 2010) are centered mostly on the reification of “groups.” For the current study, careful consideration was given to avoid reification. In line with Brame et al. (2012: 485), GBTM is viewed as a valuable tool to identify “etiologically significant” trajectories of gang membership that may be used for “developing new theoretical propositions and testable hypotheses.” The observation of adulthood onset of gang membership would be most obvious example of the utility of GBTM—adolescent onset of gang membership is a common assumption. When common developmental growth patterns are assumed, a multivariate normal distribution of the growth parameters (i.e., HLM) is ideal (Nagin 2005; Raudenbush 2001). Of course, the life-course framework presented above anticipates qualitative differences in the growth patterns, with some research confirming such an expectation (e.g., Lacourse et al. 2003).

The reported prevalence rate of gang membership in Snyder and Sickmund’s (2006) report using the NLSY97 is also 8 %. Their figure was based on the first five annual survey waves (p. 70) and an “ever” measure. It is unclear whether this estimate was nationally weighted. Using the methods described above, the current study finds a cumulative gang membership prevalence of 7 % by wave 5.

The parameters for the models are as follows: cumulative (intercept = 1.67, linear term = 2.05, quadratic term = 0.29, and cubic term = 0.45) and dynamic (intercept = −1.32, linear term = −1.42, quadratic term = −0.48, and cubic term = 0.62), where p < .05 for all estimates.

A 6-trajectory solution best fit the data according to several determinants of model fit, including the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC = −4130), the group weighted Average Posterior Probability (AvePP = 0.81), and the mean Odds of Correct Classification (OCC = 35). All of the fit statistics exceed Nagin’s (2005) recommendations. More parsimonious 4- and 5-trajectory solutions produced better AvePP and OCC values, although statistically worse BIC values. The 6-trajectory solution was chosen because the objective of the current study was to understand a more complex reality surrounding the age grading of gang membership. The emergence of an adult-onset trajectory, comprising nearly one-fifth of the gang subsample, and better discerning the onset of adolescence gang membership, indicates that this solution better approximated this reality, consistent with the GBTM (Brame et al. 2012; Nagin 2005) and gang (Krohn and Thornberry 2008) literatures. While beyond the scope of the current study, the etiological and behavior significance of these trajectories remain a priority for future inquiry.

Consistent with the hypothesis, these results are based on analyses using the full sample. When conducting the analysis using only the gang subsample it is noteworthy that statistical differences across the demographics of interest did not emerge until ages 14–15. In other words, in relation to Fig. 4, disproportionality is less a story of the “front half” of the growth curve than it is the “back half,” in terms of persistence and late onset.

This value drops to 36 and 31% when the “adulthood” cut-point shifts to 19 and 20, respectively. Arnett’s (2000) proposed new developmental period of “emerging adulthood” confronts the traditional conceptualization of adolescence-to-adulthood transitions. It is unclear how well Arnett’s concept extends into the study of gangs, although Krohn et al. (2011) offer evidence on adolescent gang membership and precocious transitions during the transition to adulthood.

References

Adamson C (2000) Defensive localism in white and black: a comparative history of European-American and African-American youth gangs. Ethn Racial Stud 23:272–298

Arnett JJ (2000) Emerging adulthood: a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am psychol 55(5):469

Barrows J, Huff CR (2009) Gangs and public policy: constructing and deconstructing gang databases. Criminol Public Policy 8:675–703

Bellair PE, McNulty TL (2009) Gang membership, drug selling, and violence in neighborhood context. Justice Q 26(4):644–669

Bjerk D (2009) How much can we trust causal interpretations of fixed-effects estimators in the context of criminality? J Quant Criminol 25:391–417

Blokland AJ, Nagin D, Nieuwbeerta P (2005) Life span offending trajectories of a Dutch conviction cohort. Criminology 43:919–954

Braga AA (2012) Focused deterrence strategies and the reduction of gang and group-involved violence. In: DeLisi M, Conis PJ (eds) Violent offenders: theory, research, policy and practice, 2nd edn. Jones & Bartlett, Burlington, pp 259–279

Brame R, Paternoster R, Piquero AR (2012) Thoughts on the analysis of group-based developmental trajectories in criminology. Justice Q 29:469–490

Bursik RJ Jr, Grasmik HG (1993) Neighborhoods and crime: The dimensions of effective community control. Lexington, New York

Coughlin BC, Venkatesh S (2003) The urban street gang after 1970. Ann Rev Sociol 29:41–64

Craig WM, Vitaro F, Gagnon C, Tremblay RE (2002) The road to gang membership: Characteristics of male gang and nongang members from ages 10 to 14. Soc Dev 11:53–68

Cullen FT (2011) Beyond adolescence-limited criminology: Choosing our future—The American Society of Criminology 2010 Sutherland address. Criminology 49:287–330

Curry GD (2000) Self-reported gang involvement and officially recorded delinquency. Criminology 38:1253–1274

Curry GD, Decker SH, Pyrooz DC (2013) Confronting gangs: Crime and community, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Decker SH (2003) Policing gangs and youth violence. Wadsworth, Belmont

Decker SH, Curry GD (2002) I’m down for my organization: The rationality of responses to delinquency, youth crime, and gangs. In: Piquero AR, Tibbetts SG (eds) Rational choice and criminal behavior: Recent research and future challenges. Routledge, New York, pp 197–218

Decker SH, Van Winkle B (1996) Life in the gang: family, friends, and violence. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Decker SH, Melde C, Pyrooz DC (2013a) What do we know about gangs and gang members and where do we go from here? Justice Q 30:369–402

Decker SH, Pyrooz DC, Moule RM Jr. (2013b). Gang disengagement as role transitions. J Res Adolesc. doi:10.1111/jora.12074

DeLisi M, Piquero AR (2011) New frontiers in criminal careers research, 2000–2011. J Crim Justice 39:289–301

DeLisi M, Spruill JO, Peters DJ, Caudill JW, Trulson CR (2012) “Half In, Half Out:” gang families, gang affiliation, and gang misconduct. Am J Crim Justice. doi:10.1007/s12103-012-9196-9

Densley J (2012) Street gang recruitment: Signaling, screening, and selection. Soc Probl 59:301–321

Egley A Jr., Howell JC (2012) Highlights of the 2010 national youth gang survey. Juvenile Justice Fact Sheet. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Washington, DC

Egley A Jr, Howell JC, Major AK (2006) National Youth Gang Survey 1999–2001. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Washington, DC

Elder GH Jr, Giele JZ (2009) Life course studies: An evolving field. In: Elder GH Jr, Giele JZ (eds) The craft of life course research. Guilford, New York, pp 1–24

Esbensen F-A, Carson DC (2012) Who are the gangsters? An examination of the age, race/ethnicity, sex, and immigration status of self-reported gang members in a seven-city study of American youth. J Contemp Crim Justice 28:465–481

Esbensen F-A, Huizinga D (1993) Gangs, drugs, and delinquency in a survey of urban youth. Criminology 31:565–589

Esbensen F-A, Peterson D, Taylor TJ, Osgood DW (2012) Results from a multi-site evaluation of the G.R.E.A.T. program. Justice Q 29:125–151

Esbensen F-A, Winfree LT Jr, He N, Taylor TJ (2001) Youth gangs and definitional issues: When is a gang a gang, and why does it matter? Crime Delinquency 47:105–130

Farrington DP (2003) Developmental and life-course criminology: key theoretical and empirical issues—the 2002 Sutherland Award Address. Criminology 41:221–256

Farrington DP, Joliffe D, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Hill KG, Kosterman R (2003) Comparing delinquency careers in court records and self-reports. Criminology 41:933–958

Garot R (2010) Who you claim: Performing gang identity in schools. New York University Press, New York

Glueck S, Glueck E (1950) Unraveling juvenile delinquency. The Commonwealth Fund, New York

Gordon RA, Lahey BB, Loeber R, Kawai E, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Farrington DP (2004) Antisocial behavior and youth gang membership: Selection and socialization. Criminology 42:55–89

Gravel J, Bouchard M, Descormiers K, Wong JS, Morselli C (2013) Keeping promises: A systematic review and a new classification of gang control strategies. J Crim Justice 41:228–242

Hagedorn JM (1988) People and folks: Gangs, crime and the underclass in a rustbelt city. Lakeview Press, Chicago

Hill KG, Lui C, Hawkins JD (2001) Early precursors of gang membership: a study of Seattle youth. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, December 1–6. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Washington, DC

Horowitz R (1983) Honor and the American dream. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick

Howell JC (2012) Gangs in America’s communities. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Howell JC, Egley AR Jr (2005) Moving risk factors into developmental theories of gang membership. Youth Violence Juv Justice 3:334–354

Huff CR (1998) Comparing the criminal behavior of youth gangs and at-risk youths. U.S. Department Of Justice, Washington DC

Jones BL, Nagin DS (2007) Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociol Methods Res 35:542–571

Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K (2001) A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res 29:374–393

Katz CM, Schnebly SM (2011) Neighborhood variation in gang member concentrations. Crime Delinquency 57:377–407

Katz CM, Webb VJ (2006) Policing gangs in America. Cambridge University Press, New York

Klein MW (2001) Forward. In: Millers J (ed) One of the guys: girls, gangs, and gender. Oxford University Press, New York

Klein MW, Maxson CL (2006) Street gang patterns and policies. Oxford University Press, New York

Krohn MD, Thornberry TP (2008) Longitudinal perspectives on adolescent street gangs. In: Liberman AM (ed) The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research. National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC, pp 128–160

Krohn MD, Ward JT, Thornberry TP, Lizotte AJ, Chu R (2011) The cascading effects of adolescent gang involvement across the life course. Criminology 49:991–1028

Lacourse E, Nagin D, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Claes M (2003) Developmental trajectories of boys’ delinquent group membership and facilitation of violent behaviors during adolescence. Dev Psychopathol 15:183–197

Lacourse E, Nagin D, Vitaro F, Cote S, Arseneault L, Tremblay RE (2006) Prediction of early-onset deviant peer group affiliation: A 12-year longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63:562–568

Lasley JR (1992) Age, social context, and street gang membership: Are “youth” gangs becoming “adult” gangs? Youth Soc 23:434–451

Laub JH (2004) The life course of criminology in the United States—The American Society of Criminology 2003 Presidential Address. Criminology 42:1–26

Laub JH, Sampson RH (2003) Shared beginnings, divergent lives: Delinquent boys to age 70. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Maxson C (2011) Street gangs. In: Wilson JQ, Petersilia JW (eds) Crime and public policy. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 158–182

Maxson CL, Whitlock ML, Klein MW (1998) Vulnerability to street gang membership: Implications for practice. Soc Serv Rev 72:70–91

McGloin J (2007) The continued relevance of gang membership. Criminol Public Policy 6:801–811

Melde C, Esbensen F-A (2011) Gang membership as a turning point in the life course. Criminology 49:513–552

Melde C, Esbensen F-A (2013) Gangs and violence: Disentangling the impact of gang membership on the level and nature of Offending. J Quant Criminol 29:143–166

Melde C, Diem C, Drake G (2012) Identifying correlates of stable gang membership. J Contemp Crim Justice 28:482–498

Miller WB (1977) Violence by youth gangs and youth groups as a crime problem in major American cities. National Institute of Justice, Washington DC

Moore JW (1991) Going down to the barrio: homeboys and homegirls in change. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA

Moule RK Jr, Decker SH, Pyrooz DC (2013) Social capital, the life-course, and gangs. In: Gibson CL, Krohn MD (eds) Handbook of life-course criminology: Emerging trends and directions for future research. Springer, New York, pp 143–158

Nagin D (2005) Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Nagin DS, Piquero AR (2010) Using the group-based trajectory model to study crime over the life course. J Crim Justice Educ 21:105–116

National Gang Center (2013) National Youth Gang Survey Analysis. http://www.nationalgangcenter.gov/Survey-Analysis

Padilla FM (1992) The gang as an American enterprise. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick

Piquero AR (2008) Taking stock of developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course. In: Liberman AM (ed) The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research. Springer, New York, pp 23–78

Piquero AR, Brame R, Mazerolle P, Haapanen R (2002) Crime in emerging adulthood. Criminology 40:137–170

Piquero AR, Farrington DP, Blumstein A (2003) The criminal career paradigm: Background and recent developments. In: Tonry M (ed) Crime and justice: a review of research, vol 30. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 359–506

Piquero AR, Farrington DP, Blumstein A (2007) Key issues in criminal career research: New analyses of the Cambridge Study of Delinquent Development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Pyrooz DC, Decker SH, Webb VJ (2010a) The ties that bind: desistance from gangs. Crime Delinquency. doi:10.1177/0011128710372191

Pyrooz DC, Fox AM, Decker SH (2010b) Racial and ethnic heterogeneity, economic disadvantage, and gangs: A macro-level study of gang membership in urban America. Justice Q 27:867–893

Pyrooz DC, Decker SH, Fleisher MS (2011) From the street to the prison, from the prison to the street: Understanding and responding to prison gangs. J Aggress Confl Peace Res 3:12–24

Pyrooz DC, Sweeten G, Piquero AR (2013) Continuity and change in gang membership and gang embeddedness. J Res Crime Delinquency 50:239–271

Raudenbush SW (2001) Comparing personal trajectories and drawing causal inferences from longitudinal data. Annu Rev Psychol 52:501–525

Robins L (1978) Sturdy childhood predictors of adult antisocial behaviour: Replications from longitudinal studies. Psychol Med 8:611–622

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (2005) A life-course view of the development of crime. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 602:12–45

Sanchez-Jankowski M (1991) Islands in the street: Gangs and American urban society. University of California Press, Berkeley

Shute J (2011) Family support as a gang reduction measure. Child Soc 27:48–59

Skardhamar T (2010) Distinguishing facts and artifacts in group-based modeling. Criminology 48:295–320

Snyder HN, Sickmund M (2006) Juvenile offenders and victims: 2006 National Report. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Washington, DC

Spergel IA (1995) The youth gang problem: A community approach. Oxford University Press, New York

Sweeten G, Pyrooz DC, Piquero AR (2013) Disengaging from gangs and desisting from crime. Justice Q 30:469–500

Tapia M (2011) Gang membership and race as risk factors for juvenile arrest. J Res Crime Delinquency 48:364–395

Thornberry TP, Porter PK (2001) Advantages of longitudinal research designs in studying gang behavior. In: Klein MW, Kerner H-J, Maxson CL, Weitekamp EGM (eds) The Eurogang paradox: Street gangs and youth groups in the U.S. and Europe. Kluwer, Dordrecht

Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Chard-Wierschem D (1993) The role of juvenile gangs in facilitating delinquent behavior. J Res Crime Delinquency 30:55–87

Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Smith CA, Tobin K (2003) Gangs and delinquency in developmental perspective. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Thrasher FM (1927) The gang: A study of 1,313 gangs in Chicago. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Trulson CR, Caudill JW, Haerle DR, DeLisi M (2012) Cliqued up: The postincarceration recidivism of young gang-related homicide offenders. Criminal Justice Review 37:174–190

van Mastrigt SB, Farrington DP (2009) Co-offending, age, gender, and crime type: Implications for criminal justice policy. Br J Criminol 49:552–573

Venkatesh S (2008) Gang leader for a day. Penguin Books, New York

Vigil JD (1988) Barrio gangs: Street life and identity in Southern California. University of Texas Press, Austin

Vigil JD (2002) A rainbow of gangs: Street cultures in the mega-city. University of Texas Press, Austin

Warr M (2002) Companions in crime: The social aspects of criminal conduct. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Watkins AM, Moule RK, Jr. (in press). Older, wiser, and a bit more badass? Exploring differences in juvenile and adult gang members’ gang-related attitudes and behaviors. Youth Violence Juv Justice. doi:10.1177/1541204013485607

Weitzer R (2010) Race and policing in different ecological contexts. In: Rice SK, White MD (eds) Race, ethnicity, and policing: New and essential readings. New York University Press, New York, pp 118–139

West DJ, Farrington DP (1973) Who becomes delinquent? Second report of the Cambridge study in delinquent development. Heinemann, London

Wilson William J (1987) The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Wise R, Robbins (1961) West side story. Mirisch Pictures, United States

Wolfgang ME, Figlio RM, Sellin T (1972) Delinquency in a birth cohort. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Young JTN, Rees C (2013) Social networks and delinquency in adolescence: Implications for life-course criminology. In: Gibson CL, Rees C (eds) Handbook of life-course criminology: Emerging trends and directions for future research. Springer, New York, pp 159–180

Zatz Marjorie S (1987) Chicano youth gangs and crime: The creation of a moral panic. Crime Law Soc Change 11:129–158

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Graduate Research Fellowship from the National Institute of Justice (2011-JP-FX-0101) and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2011-JV-FX-0004). I am grateful for their support. The content and opinions expressed in this document are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of these agencies. I would like to thank Scott Decker, Rick Moule, Gary Sweeten, and Vince Webb for their comments on this manuscript, and well as the editors of JQC and the anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pyrooz, D.C. “From Your First Cigarette to Your Last Dyin’ Day”: The Patterning of Gang Membership in the Life-Course. J Quant Criminol 30, 349–372 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-013-9206-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-013-9206-1