Abstract

Introduction The aim of this systematic review was to study factors which promote or hinder young disabled people entering the labor market. Methods We systematically searched PubMed (by means of MESH and text words), EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science and CINAHL for studies regarding (1) disabled patients diagnosed before the age of 18 years and (2) factors of work participation. Results Out of 1,268 retrieved studies and 28 extended studies from references and four from experts, ten articles were included. Promoting factors are male gender, high educational level, age at survey, low depression scores, high dispositional optimism and high psychosocial functioning. Female and low educational level gives high odds of unemployment just like low IQ, inpatient treatment during follow up, epilepsy, motor impairment, wheelchair dependency, functional limitations, co-morbidity, physical disability and chronic health conditions combined with mental retardation. High dose cranial radiotherapy, type of cancer, and age of diagnosis also interfered with employment. Conclusions Of the promoting factors, education appeared to be important, and several physical obstructions were found to be hindering factors. The last mentioned factors can be influenced in contrast to for instance age and gender. However, to optimize work participation of this group of young disabled it is important to know the promoting or hindering influence for employment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about 10% of the world population experiences some form of physical or mental disability. Of these approximately 650 million disabled people, 200 million are children. The number of disabled children is increasing due to population growth, increases in chronic diseases and medical advances that preserve and prolong life [1].

Disabled children experience barriers when they enter the labor market due to their physical or mental limitations, and many more of these starters are unemployed compared to non-disabled starters [2, 3]. A survey study in the USA found that 32% of people with disabilities were working, versus 81% of people without disabilities [4]. This, in turn, leads to a variety of economic, social and quality of life problems [5–8].

Although some of the disabled starters are unable to work in any way because of their limitations, others can and are willing to work. However, to gain employment when they reach working age, they need to be prepared for the labor market. If we can determine factors that help or hinder young disabled people in finding employment, we may be able to better assess their abilities, and thereby help them to prepare for the labor market.

Factors that influence work participation can be disease-related but also external and personal as notified by the WHO’s international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) framework [9, 10]. This framework states that the functioning of an individual is not only influenced by factors related to a disease or disorder, and that external and personal factors can also have positive, promoting, or negative, hindering, influences [9].

Although there are studies on disability-causing diseases and return-to-work factors among adults [11], young disabled starters at the beginning of their vocational career may face other barriers. The factors found for disabled employed adults may not be the same as those for disabled starters. To find out if there are factors reported in the literature specific to young disabled at the beginning of their vocational career, we systematically reviewed the literature. We searched for factors that generally influence work participation and, therefore, we did not limit our search to specific diseases or disorders. We included all studies among disabled young people who had not yet entered the labor market when diagnosed, and those that explain the differences in work participation among them. In this review we addressed the question: what factors are reported that promote or hinder work participation of young disabled people?

Method

Search Strategy

For this review we extensively searched biomedical and psychological databases (PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Web of Science and CINAHL) through May 2008. We included studies that described factors influencing the work participation of young disabled people, using the keywords young disabled, work/employment and factors and their synonyms. No constraints on disease types were made. In appendix, the synonyms and search strategy are listed. Inclusion criteria were:

-

1.

Written in English, German or Dutch;

-

2.

Abstract and full article available;

-

3.

Description of young disabled persons;

-

a.

Young disabled was defined as diagnosed with a disability before the age of 18 years.

-

b.

Disabled was defined as persons with physical or mental disabilities that affect or limit their activities of daily living, and that may require special accommodations (Mesh PubMed).

-

a.

-

4.

Description of work or employment as outcome measure; and

-

5.

Including factors predicting or associated with either employment or unemployment.

The reference lists of selected articles were hand-searched for additional references and experts were asked for relevant articles.

Study Selection

At first, two authors (TA en HW) independently reviewed the title and the abstracts of the studies that were selected on the basis of the inclusion criteria. If the abstracts met the inclusion criteria we included these for full text selection. If there was any doubt about inclusion of the abstract by one of the authors, the study was included for full text selection. We reviewed the full text articles again, independently. In the case of disagreement on the inclusion of an article, a third reviewer (MF) was consulted.

Data Extraction

From the included articles the following items were extracted: cause of disability; number participants in the study; age at diagnosis; gender; time since diagnosis or age at study; outcome measure; factors that had a significant influence on work participation; instruments used to measure these factors; and whether the factors had a positive or negative influence on work participation.

Results

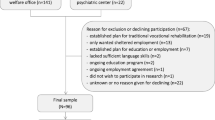

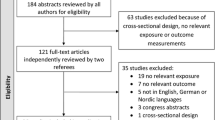

Our search resulted in 1,458 publications: 721 from PubMed, 243 from EMBASE, 338 from PsycINFO, 111 from Web of Science and 45 from CINAHL (see flowchart; Fig. 1). After removal of duplications, we reviewed 1,268 studies based on the abstract and inclusion criteria. Work as an outcome measurement, factors and study design was not always clearly described in the abstract (Table 1). Therefore, we first reviewed the abstracts on the criteria language, young, disabled and work. If the abstract met these criteria, we reviewed the full article. Using the criteria, we reviewed 66 full articles. The reference lists of these 66 articles led to an extension of 28 studies for which full texts were reviewed and four selected articles from experts [2, 12–14].

From these 98 articles, we excluded 19 studies in which the population was not diagnosed before the age of 18. In five studies it was not clear whether the population was disabled. In thirty-six studies work was not the outcome measure. In eleven studies there were no factors that explained the differences in outcome for employment. The seventeen studies with a case control design or descriptive design were excluded; the employment status of disabled young people was compared with healthy controls or siblings or the general population.

Factors

We included ten studies. We found that gender was a promoting factor: males have a higher chance for employment [12, 13, 15, 16]. Educational level was a predictive factor for employment: not only a higher educational level reached by the young disabled was positively associated with employment [13, 15, 17, 18] but also a higher parental educational level [2]. A higher level of psychosocial functioning at treatment entry and after follow up was a positive predicting factor for employment [19] among young adults with a mental disorder. A lower age at time of survey was positively associated with employment [16] among survivors of cancer. Lower scores on a depression scale and higher level of dispositional optimism were promoting factors associated with employment in a study among adults with cystic fibrosis [13].

We found also hindering factors. Educational level and gender were found as hindering factors: primary or lower educational level was associated with lower odds of employment compared with higher secondary or tertiary level [17, 18] and females had a lower chance for being employed compared with males. Inpatient treatment during follow up was a negative predicting factor for employment in the study among mental disordered young adults [19]. An IQ lower than 80 and epilepsy were hindering factors in a study among survivors of brain tumors [20]. Motor impairment, wheelchair use, functional limitations, co-morbidity, physical disability and chronic health conditions combined with mental retardation or physical disabilities were hampering factors [2, 14, 17, 20]. The type of cancer, and cranial radiotherapy with more than 30 GY interfered with employment just as age under 3 years at diagnosis among survivors of cancer. Low mental health perception, denial coping strategy and dependent coping strategy were also found as impeding factors for employment [14, 18].

Discussion

Our extensive literature study shows that there is little written about factors influencing the work participation of young disabled starters entering the labor market. We found that gender, education, high psychosocial level of functioning, low depression and high dispositional optimism were promoting factors in relation to employment. Some of these factors, like gender, education and psychosocial functioning have more impact since they were found in longitudinal studies. On the other hand, we also found several hindering factors in relation to employment among this group of young disabled. For instance, motor impairment, physical ability, co-morbidity, epilepsy, IQ lower than 80, inpatient treatment during follow up, depending and denial coping strategy and age at diagnosis and radiation grade in cancer survivors appeared to be related to negative employment outcome. Of these factors motor impairment, epilepsy, low IQ and inpatient treatment during follow up were found in longitudinal studies and therefore deserve more attention.

Although we preformed a broad-based search, the number of included studies was limited. Our search, however, was performed with a lot of synonyms and without constraints on type of disease. From the abstracts found, it was often not clear whether the study had work participation as outcome measure and/or the study design was not clear. Therefore, a great number of full articles were reviewed. However, even with this broad-based search, we only found a few articles that met all of our inclusion criteria.

There are a number of explanations that could be responsible for the low number of found studies. In clinical studies among young people work was not included as outcome measure. More often, the focus of research was on the results of medical treatment, tests to diagnose a disease, mortality or morbidity. Studies beyond treatment focused more on physical impairment, rehabilitation or educational achievement [21–23]. The fact that the patients have often not yet entered the labor market could be responsible for this lack of studies with work as a measurement outcome. However, these starters are at the very beginning of their vocational career, and if they do not enter the labor market at this point, their entire working lives could be lost. By identifying the factors that influence their work participation, a better match between work ability and work demand can be found and, if necessary, supporting interventions can be developed.

Another reason for the scarcity of included studies could be that in some studies, which used work participation as an outcome, factors were lacking that explained the differences in outcome among disabled young people [22, 23]. These studies concluded that there was more unemployment among disabled compared with healthy controls or general population without further elucidation. However, such a conclusion does only partly contribute to a better insight on what factors among young disabled people determine work participation.

In a number of studies [7, 23], there were discussions about whether or not disability was still present. In these studies, there had been a serious disease during childhood but the patients survived and recovered, and were declared physically fit/healthy. The focus of our search was on factors among disabled young people, and survivors in these studies were excluded if there was no description of disability anymore. Therefore, the survivors could not be seen as disabled in the way that we defined disabled: persons with physical or mental disabilities that affect or limit the activities of daily living and that may require special accommodations. Still, it seems that having a serious disease during childhood leads to a greater risk of unemployment, compared to healthy young people [7, 22, 23]. In other studies the focus was more on the disease instead of the limitations in work participation as result of the disease although work participation was an outcome measure. These studies were not found with our search but via references and experts.

Because we found only a few studies with prognostic factors, we did not apply quality criteria. The predicting factors found in our review were also found in other studies focussing on the predicting factors of work participation of patient groups, not specially diagnosed before the age of 18. For instance, use of hospital cure during follow-up as well as gender and education were found to be predicting employment in studies among adults [24, 25]. Also several cross-sectional studies among adults showed similar results as we found in studies among young disabled influencing work participation, like psychosocial factors such as passive coping style [11, 26, 27], severe mental illness [27] and disabilities in general [11]. It is an indication that these factors might be negatively influencing employment not only among young disabled, but also among adults. Whether there is a causal relation between these factors and employment would be interesting to know. The results show personal factors and disease related factors that decrease activities and that impair and restrict the young disabled in work participation such as age, gender, education and coping style as personal and treatment, physical ability and co-morbidity as disease related factors. In our study among young disabled we did not find external factors, such as support of management and colleagues and adequate work conditions that were found in studies among adult employees [28]. However, it can be imagined that these factors are of great importance in keeping the young disabled employed.

Some of the factors found in this study are not changeable, such as age or IQ, but other factors can be influenced. When for instance education is found to be an important promoting factor for employment, attention can be given to the opportunities for education for disabled young persons. On the other hand, by knowing what hindering factors exist for employment of young disabled effort can be put in avoiding these factors. Adapting workplaces might be a solution to overcome obstacles for employment due to motor impairments, wheelchair use, and other physical disabilities. Knowing the promoting and hindering factors can lead to appropriate support or intervention for the disabled starter, which could result in higher work participation and lower the barriers they experience. It is worthwhile to create adequate work places for young people with disabilities in order to give them a fulfilling life and this starts by knowing what the promoting and/or hindering factors are in relation to work participation for this population.

References

WHO. Concept note world report on disability and rehabilitation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

Ireys HT, Salkever DS, Kolodner KB, Bijur PE. Schooling, employment, and idleness in young adults with serious physical health conditions: effects of age, disability status, and parental education. J Adolesc Health. 1996;19:25–33. doi:10.1016/1054-139X(95)00095-A.

Fiedler IG, Indermuehle DL, Drobac W, Laud P. Perceived barriers to employment in individuals with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2002;7:73–82. doi:10.1310/G7N8-81XN-E12K-CCM0.

Blomquist KB. Health, education, work, and independence of young adults with disabilities. Orthop Nurs. 2006;25:168–87. doi:10.1097/00006416-200605000-00005.

Blomquist KB, Brown G, Peerson A, Presler EP. Transitioning to independence: challenges for young people with disabilities and their caregivers. Orthop Nurs. 1998;17:27–35. doi:10.1097/00006416-199805000-00005.

Boman KK, Bodegärd G. Life after cancer in childhood: social adjustment and educational and vocational status of young-adult survivors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26:354–62. doi:10.1097/00043426-200406000-00005.

Langeveld NE, Ubbink MC, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA, Voûte PA, de Haan RJ. Educational achievement, employment and living situation in long-term young adult survivors of childhood cancer in the Netherlands. Psychooncology. 2003;12:213–25. doi:10.1002/pon.628.

Bond GR, Resnick SG, Drake RE, Xie H, McHugo GJ, Bebout RR. Does competitive employment improve nonvocational outcomes for people with severe mental illness? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:489–501. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.3.489.

WHO.ICF. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

Heerkens Y, Engels J, Kuiper C, Van der Gulden J, Oostendorp R. The use of the ICF to describe work related factors influencing the health of employees. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:1060–6. doi:10.1080/09638280410001703530.

Gobelet C, Luthi F, Al-Khodairy AT, Chamberlain MA. Vocational rehabilitation: a multidisciplinary intervention. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1405–10. doi:10.1080/09638280701315060.

Broyer M, Le Bihan C, Charbit M, Guest G, Tete M, Gagnadoux MF, et al. Long-term social outcome in children after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;77:1033–7. doi:10.1097/01.TP.0000120947.75697.8B.

Burker EJ, Sedway J, Carone S. Psychological and educational factors: better predictors of work status than FEV1 in adults with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;38:413–8. doi:10.1002/ppul.20090.

Groothoff JW, Grootenhuis MA, Offringa M, Stronks K, Hutten GJ, Heymans SA. Social consequences in adult life of end-stage renal disease in childhood. J Pediatr. 2005;146:512–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.10.060.

Nagarajan R, Neglia JP, Clohisy DR, Yasui Y, Greenberg M, Hudson M, et al. Education, employment, insurance and marital status among 694 survivors of pediatric lower extremity bone tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:2554–64. doi:10.1002/cncr.11363.

Pang JWY, Friedman DL, Whitton JA, Stovall M, Mertens AC, Robison LL, et al. Employment status among adult survivors in the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2008;50:104–10. doi:10.1002/pbc.21226.

Valtonen K, Karsson A, Alaranta H, Viikari-Juntura E. Work participation among persons with traumatic spinal cord injury and meningomyelocele. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38:192–200. doi:10.1080/16501970500522739.

Packham JC, Hall MA. Long-term follow-up of 246 adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: education and employment. Rheumatol. 2002;41:1436–9. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/41.12.1436.

Pelkonen M, Marttunen M, Pulkkinen E, Laippala P, Lönnqvist J, Aro H. Disability pensions in severely disturbed in-patient adolescents. Twenty-year prospective study. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:159–63. doi:10.1192/bjp.172.2.159.

Macedoni-Lukšič M, Jereb B, Todorovski L. Long-term sequelae in children treated for brain tumors: impairments, disability, and handicap. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;20:89–101. doi:10.1080/0880010390158595.

Sillanpää M, Jalava M, Kaleva O, Shinnar S. Long-term prognosis of seizures with onset in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1715–22. doi:10.1056/NEJM199806113382402.

Flatø B, Lien G, Smerdel A, Vinje O, Dale K, Johnston V, et al. Prognostic factors in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control study revealing early predictors and outcome after 14.9 years. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:386–93.

Pui C, Cheng C, Leung W, Rai SN, Rivera GK, Sandlund J, et al. Extended follow-up of long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;34:640–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035091.

Honkonen T, Stangård E, Virtanen M, Salokangas RKR. Employment predictors for discharged schizophrenia patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:372–80. doi:10.1007/s00127-007-0180-5.

Smith Randolph D. Predicting the effect of disability on employment status and income. Work (reading, mass). 2004;23:257–66.

Smeets VMJ, van Lierop BAG, Vanhoutvin JPG, Aldenkamp AP, Nijhuis FJN. Epilepsy and employment: literature review. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10:354–62. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.02.006.

Michon HWC, Weeghel J, Kroon H, Schene AH. Person-related predictors of employment outcomes after participation in psychiatric vocational rehabilitation programmes. A systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:408–16. doi:10.1007/s00127-005-0910-5.

Detaille SI, Haafkens JA, van Dijk FJH. What employees with rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus and hearing loss need to cope at work. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2003;29:134–42.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by a grant of the SIG (Stichting Instituut GAK), The Netherlands.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Achterberg, T.J., Wind, H., de Boer, A.G.E.M. et al. Factors that Promote or Hinder Young Disabled People in Work Participation: A Systematic Review. J Occup Rehabil 19, 129–141 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9169-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9169-0