Abstract

Patient-centred care (PCC) is recommended in policy documents for chronic heart failure (CHF) service provision, yet it lacks an agreed definition. A systematic review was conducted to identify PCC interventions in CHF and to describe the PCC domains and outcomes. Medline, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ASSIA, the Cochrane database, clinicaltrials.gov, key journals and citations were searched for original studies on patients with CHF staged II–IV using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification. Included interventions actively supported patients to play informed, active roles in decision-making about their goals of care. Search terms included ‘patient-centred care’, ‘quality of life’ and ‘shared decision making’. Of 13,944 screened citations, 15 articles regarding 10 studies were included involving 2540 CHF patients. Three studies were randomised controlled trials, and seven were non-randomised studies. PCC interventions focused on collaborative goal setting between patients and healthcare professionals regarding immediate clinical choices and future care. Core domains included healthcare professional-patient collaboration, identification of patient preferences, patient-identified goals and patient motivation. While the strength of evidence is poor, PCC has been shown to reduce symptom burden, improve health-related quality of life, reduce readmission rates and enhance patient engagement for patients with CHF. There is a small but growing body of evidence, which demonstrates the benefits of a PCC approach to care for CHF patients. Research is needed to identify the key components of effective PCC interventions before being able to deliver on policy recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a life-limiting progressive condition [1, 2] predominantly affecting elderly patients with multiple co-morbidities [3]. Treatment advances have increased prognosis and treatment options with more patients now living with advanced CHF [4]. In a condition with a comparable mortality rate to cancer [5], patients experience a considerable illness burden [6], reduced quality of life [7] and high levels of uncertainty particularly for the future [8]. As treatment options have increased, treatment decisions have become more challenging for patients and clinicians [9]. This is compounded by patients who poorly understand their prognosis [10], overestimate the benefits of life-prolonging treatments [11] and fail to appreciate the detrimental effect these treatments can have on their quality of life [9]. Older patients may have a preference for prolonged independence, better cognitive and physical function over life-prolonging treatments, if given the informed opportunity to choose [12–14]. Patient-centred care (PCC) answers to this challenge by incorporating patients’ preferences, values, beliefs, illness understanding, illness experience and information needs into the decision-making process, thus encouraging patient engagement and collaborative goal setting [15, 16].

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) [17], the European Society of Cardiology [18] and the American Heart Association [9] have recommended a patient-centred approach for CHF. Health policy recommends a patient-centred approach [19–21], but an agreed global definition is lacking [22, 23]. Domains common to the concept of PCC in the literature include: respect for patients’ needs [19, 24–30], values [19, 25–27, 29–32] and preferences [19, 23–30, 32, 33], patient–healthcare professional collaboration [19, 22, 24–33] and shared decision-making [19, 23–28, 31–33]. In chronic illness—such as CHF—patients must navigate through complex information and treatment choices while experiencing the ramifications of chronic ill health on their lives. Health policy supports the role of patients as informed, active and prepared decision-makers in their own health care, rather than passive recipients [23, 29, 34–36]. In the move away from a paternalistic disease-focused approach, PCC actively encourages patient involvement [26] while recognising the patient as a ‘whole person’ rather than merely experiencing a disease process. In chronic illness, PCC has a beneficial effect on healthcare professional–patient concordance regarding treatment plans, patient health outcomes and patient satisfaction [37] and respects patients’ desired level of involvement in healthcare decisions [38, 39]. The central domains of PCC are also found in the concept of the palliative care approach to CHF management which explicitly views these PCC domains in the context of CHF as a life-threatening disease. Additionally, the palliative care approach states that its central goal is improvement of quality of life for both patient and family [40]. Fundamental to both is shared decision-making (SDM). Good PCC which is being examined here manifests as SDM; patient–healthcare professional collaboration ensures that patients’ values, needs and preferences are met and evidence and clinical experience guide the decision-making process [23, 28, 37, 39].

To our knowledge, no systematic review has examined the evidence for PCC interventions in CHF. This review therefore aims (i) to identify PCC interventions in CHF where patients’ are involved as informed, active participants in SDM about their clinical care and identify their own personal care goals and (ii) to describe domains of PCC included in the interventions and to describe the selected outcomes of these studies.

Methods

With no agreed definition and heterogeneity in its operationalisation, assessing PCC as an effective approach to care presents a challenge. SDM, where healthcare professionals and patients are involved in making care decisions, involves a process of sharing information, identifying preferences and goals to reach common ground to enable the delivery of optimal health care to the patient [28, 30, 41, 42]. SDM has been identified as an essential component of PCC for CHF [9, 41]. It has been used in other systematic reviews as a reasonable indicator of PCC [42, 43]. As PCC implementation in clinical practice is a relatively new research area, a broad search strategy with a high sensitivity was preferred to a very specific search. A protocol was written, and a combination of database searches used in previous systematic reviews for PCC [42, 43], SDM [44] and quality of life [45] were modified based on scoping searches to include ‘patient empowerment’ and ‘self-care’ to increase sensitivity to intervention studies focusing on these PCC components. End-of-life care and advance care planning terms did not notably increase sensitivity and were omitted. Final search terms included ‘heart failure’ AND (‘patient-centred care’, OR ‘shared decision making’ OR ‘self-care’ OR ‘patient empowerment’) AND (‘quality of life’ OR ‘communication’ OR symptoms). Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ProQuest ASSIA, Cochrane databases and clinicaltrials.gov were searched from inception to March 2015. This was supplemented by contacting authors, hand-searching bibliographies of PCC interventions reviews [8], key journals (European Journal of Heart Failure, Journal of Cardiac Failure) and citation and reference searches. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database were searched to capture unpublished literature (for search strategy, see Appendix of ESM).

One author (PMK) reviewed the abstracts and retrieved papers that fulfilled the criteria for closer scrutiny (Table 1). Two authors (PMK and CES) screened 10 % of abstracts to ensure agreement. Studies were included for data extraction if >40 % of participants had CHF (NYHA II–IV), the intervention included SDM and patient-centred outcome(s) were measured. Mixed studies were included where quantitative data fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Data extracted by PMK included: study design, intervention, setting, attrition rate, outcome(s) and PCC domains within interventions. Two authors (PMK and CES) assessed the quality of included studies using the Down and Black checklist for RCTs and non-RCTs [46]. Qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis to identify PCC benefits or barriers [47]. Quantitative studies were to be analysed using pooled odds ratio or meta-analysis, if possible [48]. If not possible due to the number or type of studies or heterogeneity, results were to be analysed using the clustered intervention approach (with clusters consisting of interventions, outcomes or elements) and/or in tabular format to aid interpretation [49].

Results

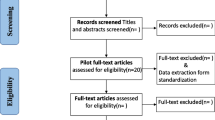

The search retrieved 13,944 papers and a reference scan yielded 5 additional papers, as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) [50]. Of 12,078 papers screened at title and abstract, 12,020 papers were excluded, leaving 58 papers for full-text review. Forty-three papers were excluded as they did not fulfil the inclusion criteria. Fifteen papers were included regarding 10 studies with 3 additional articles regarding 1 study [51–53] and 2 additional articles regarding another study [54, 55].

A total of 2540 patients were included in 10 studies. Study characteristics are outlined in Table 2. 2 studies were based on an inpatient hospital setting [56, 57] with the remainder in outpatients or community settings. 3 studies used a mixed-method approach to explore patients’ perceptions of the PCC intervention [52, 53, 56, 58, 59]. Two explored perceived intervention acceptability and impact [57, 60].

Sample size ranged from 24 to 1894, with an average age of 75 years and a high attrition rate. Three studies were phase II RCTs [61–64]. Two non-RCTs were controlled before and after studies [56, 60]. A meta-analysis was not possible due to the small number and heterogeneity of included studies. The majority of participants were male, NYHA functional class II–III with at least 3 co-morbidities. While all interventions involved SDM (defined earlier), the tools and techniques used were heterogeneous. The median quality score was 20 (possible total score of 32) (Table 2). The majority of papers scored well on reporting (median 10.5, possible total of 11) and external validity (median 3, possible total of 3) with poorer scores on internal validity (median 7, possible total of 13, combined score for selection and confounding bias) and power (median 0.0 possible total of 5).

A framework of commonly identified PCC domains was compiled from a literature review [19, 22–33]. Table 3 shows this framework and lists the common PCC domains together with the patterns of emphasis in included studies. The study by Ekman et al. [56] which involved PCC implementation at ward level and the studies which involving specialist palliative care as an intervention [57, 59, 61, 65] included most patient-centred domains. In addition to SDM, patient–healthcare professional collaboration, patient involvement in identification of goals of care, ascertainment of patient’s treatment preferences and patient activation were the most commonly identified domains.

The common components of the interventions are shown in Fig. 2.

Holistic assessment

Six studies included comprehensive assessments of patients’ physical, psychosocial [56, 60, 66] and spiritual needs [59, 61, 65] which provided information on patients’ understanding of their illness, its impact on their lives and their care preferences.

SDM

Decision content ranged from immediate healthcare choices to advance care planning. Five studies involved advance care planning [57, 59, 61, 65, 66]. Specialist palliative care initiated and was involved in these discussions in 4 of these studies [57, 59, 61, 65]. In the implementation study by Schellinger et al. [66], trained facilitators discussed advance care planning with patients. Five studies focused on more immediate symptom management [56, 58, 60, 62, 63], of which 3 used motivational techniques to achieve greater concordance between patients’ goals and values and their current behaviour [58, 62, 63].

Education and training

Seven studies included an educational component [56, 58–60, 62, 63, 66], of which 3 involved healthcare professional education and training [56, 58, 66]. Ekman et al. [56] provided a 3-h introduction on the theory and application of PCC to ward staff. In the Riegel et al. [58] study, a nurse was trained in a motivational approach and family counselling prior to providing patient home visits. Schellinger et al. [66] implemented the Respecting Choices Disease Specific Advance Care Planning (DS-ACP) [67] where trained facilitators received 26 h of competency-based communication skills training. Delaney et al. [60] provided a manual on guidelines to nurses delivering the intervention and an patient education booklet. Shively et al. [63] provided a patient education booklet with a nurse-delivered behavioural management programme. Dionne-Odom et al. [59] gave patients a workbook which they completed with nursing support. Shively et al. [62] gave patients an educational booklet and DVD.

Multidisciplinary approach

Brannstrom et al. [61] was the only study to use a multidisciplinary approach to deliver PCC. Patients were given access to specialists (nurses and physicians) in palliative care and CHF care, together with physiotherapists and occupational therapists.

Support

Family support was investigated in six interventions [56, 57, 61, 63, 65]. One study found that a lack of family support could act as a barrier to accessing available care [58].

Outcome measures

The outcomes are outlined in Table 2 and in Fig. 3.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

Six studies measured HRQoL using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) [56, 59, 61] or the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) [60, 63, 65]. Delaney et al. [60], Evangelista et al. [65] and Brannstrom et al. [61] showed a significant improvement in HRQoL (p = 0.007; p < 0.035; p = 0.047).

Symptom burden

Four studies measured symptom burden [59–61, 65]. Two studies used the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) [61, 65]; Evangelista et al. [65] showed a significant improvement in the total score (p < 0.001), while Brannstrom et al. [61] found a significant improvement in nausea in the intervention group (p = 0.02). Evangelista et al. [65] showed a significant improvement (p < 0.005) in depression measured with the Patient-Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) as did Delaney et al. (p = 0.001) [60].

Patient activation

Six studies included patient activation or engagement in the intervention description [55, 56, 58, 60–62]. Two studies measured patient activation with the Patient Activation Measure (PAM). Both showed a significant increase in patient activation (p < 0.001; p = 0.03) [55, 62]. Better symptom recognition and management and additional palliative care support increased patient activation [55] and reduced the uncertainty experienced from high symptom burden, which can undermine patients’ sense of control [51].

Functional capacity

Ekman et al. [56] found a significant preservation in functional capacity as measured with the Katz ADL (p = 0.04). Shively et al. [63] demonstrated a significant improvement in functional capacity with the Medial Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey, Veterans adapted version (SF-36V) (p = 0.03).

Ekman et al. [56] and Brannstrom et al. [61] showed significant reductions in hospital length of stay (2.5 days shorter, median 6.5, p = 0.01) and readmission rates (15 vs. 53, p = 0.009), respectively.

Qualitative data

Three themes were identified from qualitative data where available in the form of participant quotes and related authors’ commentary [52, 53, 56–60, 66]; staff and patient communication; patient engagement; and implementation. Patients appreciated staff empathy [58], trustworthiness, expertise [60] and being listened to by staff [53]. This relationship facilitated patients to become more engaged in their care [53, 60], to negotiate an agreed plan of care [58], to access information [60], to address misconceptions about heart failure [58] and to identify both barriers and available resources to adapt to life with CHF [53, 58, 59].

Discussion

This is the first review of PCC interventions in CHF. It found that PCC improves HRQoL [60, 61, 65], symptom burden [61, 65], depression [60, 65] and patient activation [55, 61, 62]. Of 10 studies identified, 3 were phase II RCTs and 2 were controlled before and after studies. There are methodological limitations with some studies underpowered due to a small participant number. The strength of evidence is moderate to low; reporting and external validity scored moderately [46]. These findings demonstrate that PCC has a beneficial role in the provision of care to patients with CHF. However, further research is needed to identify the effective components of PCC interventions to inform policy recommendations and clinical practice guidelines.

The interventions had common components including patient assessment, education and healthcare professional–patient collaboration. These commonalities are reflected in the PCC framework where frequently identified domains included healthcare professional–patient collaboration, patient engagement and identification of patient preferences and goals of care. PCC sits within the Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions (ICCC) framework [35] and as a model of care encourages patients’ central role and responsibility for their health care while seeking to address the fragmented healthcare management of these patients with chronic conditions and multi-morbidity experience [36]. Where interventions included patient assessments, these involved a comprehensive assessment of patients’ needs, values and preferences [56, 57, 59–61, 65] which lays the foundation for PCC [37] and better care coordination in chronic disease [36]. Most interventions included education and training to healthcare professionals, patients or both. Training healthcare professionals in patient-centred skills enable them to provide PCC to their patients [42]. Patient education facilitates PCC as well-informed patients are better prepared and ‘activated’ to engage in care discussions [15, 36]. Patient activation describes patients who have the knowledge, skills and motivation to participate and engage in the management of their care [68]. A moderate level of evidence (three RCTs and two controlled before and after studies) demonstrated that interventions which enable patient engagement improve HRQoL [61], symptom burden [61], physical functioning [56, 63] and patient activation [61, 62]. All of the interventions involved multiple patient interactions, which allowed the patient–healthcare professional relationship to develop and is a recognised PCC facilitator [33].

There were common challenges identified across the studies. Recruitment was challenging and 4 studies had ≥20 % attrition rates [56, 58, 59, 66], which is not uncommon in CHF given symptom volatility, high mortality and the subjective nature of the NYHA classification system [69]. Intervention implementation was only partially successful. Qualitative staff interviews by Ekman et al. [56] found that staff given PCC education poorly understood this approach or thought they practiced PCC already [52]. Staff training is dependent on staff ability and willingness to translate received training into clinical practice [70]. PCC interventions designed to involve direct patient contact may be more efficacious than staff training alone [23]. Where interventions involved palliative care or advance care planning, staff felt ill-equipped to have discussions regarding these with patients [57, 66]. This reflects a larger challenge in CHF care where a cultural change is required to increase palliative care awareness and address suboptimal palliative care access [18]. PCC shares a similar philosophy to patient engagement and SDM as palliative care. PCC may prove to be a valuable facilitator to the appropriate integration of palliative care into CHF management, as physical and psychological symptoms are recognised and alleviated in a timely manner and patient activation increased. Embedding a holistic approach to care in usual practice and aligning goals of care to patients’ expressed wishes should encourage consideration of the patient’s management in the context of an illness journey or trajectory rather than in the context of disjointed episodes of decompensation. This should lead healthcare professionals to incorporate a palliative care approach into their own practice or to seek specialist palliative care involvement, where appropriate.

A gap exists between PCC policy recommendations in CHF and clinical practice. No agreement exists as to what PCC should look like in clinical practice for this population. CHF quality indicators include discharge instructions, medication use and smoking cessation [71], but none encompass PCC components. Quality indicators are evidence- or consensus-based measurable markers of practice performance, which can be used to assess the quality of care [72]. This deficit has implications for guideline development and clinical practice. An appraisal of ICD implantation clinical practice guidelines found major deficiencies in decision-making recommendations with an emphasis on device effectiveness and little advice on discussions regarding quality of life or the psychological impact [73]. A British cardiology trainees’ survey supported this finding; only 9.4 % of trainees involved in ICD insertion always discussed the future possibility of device deactivation with patients [74]. Quality indicators identified for patient-centred cancer care include communication, physical support and psychosocial support [75]. NICE in its CHF quality statement identified the following quality measures: personalised patient information; education; support; and the opportunity for patients to increase their understanding of their condition and to be involved in its management [76]. NICE recommend that where no quality indicators exist that quality measures may form a basis for their development [76].

The interventions were multifaceted and complex, and the number of retrieved studies was small. A systematic review of the efficacy of PCC interventions suggests that the challenges associated with designing a complex intervention encompassing this concept may contribute to this paucity of research [8]. However, given that 8 of the 10 included studies were published within the last 5 years, this is a growing body of research. The heterogeneity of outcomes made comparisons difficult and illustrates the challenge in identifying the most appropriate outcome(s) to measure the potential effect of PCC as a multifaceted concept. Five studies identified a primary outcome; improvement in mean symptom burden [61, 65]; patient activation [62]; length of hospital stay (LOS) [56]; and exercise performance [63]. All bar exercise performance showed a significant improvement. Two RCTs demonstrated a significant improvement in their primary outcome; patient activation [62] and nausea, respectively [61]. No study included cost as an outcome measure. PCC reduces readmissions and LOS as shown here and is a strategy to reduce unwanted high-cost interventions by identifying patients’ care preferences [23]. Research is needed into its cost-effectiveness. Few studies included process measures, yet process measures are needed to help identify the effective components of these complex interventions to inform clinical practice.

PCC seeks to improve quality of care by improving patient experience which is of increasing interest at a policy level [19]. Three studies included qualitative research methods to explore the patients’ experience, which gave valuable insights into the potential mechanism of action and effective components of the interventions [52, 56, 58, 59]. The use of qualitative research methods in combination with quantitative research methods helps to answer questions about patient experience which quantitative research methods alone are unable to answer in these complex interventions [77].

Strengths and limitations

PCC has been a MeSH heading since 1995. Interventions with components of PCC do not necessarily include PCC as a keyword, in the title or abstract. The search strategy was broad to address this and was combined with reference hand searching which retrieved a large number of references. Despite these measures, relevant studies may have been missed. In some papers, intervention components were poorly described resulting in the exclusion of those particular studies. Heart failure disease management clinics are now standard care in CHF with extensive literature on these. Disease management programmes may encompass domains of PCC, but these interventions are frequently poorly described in the literature [78], which presents a challenge when trying to capture all the relevant studies. Bias may have been introduced as the second reviewer only screened 10 % of the titles and abstracts. Screening of all references was undertaken twice by the first reviewer, but given the large number of citations, a relevant paper may still have been missed. The second reviewer was not involved in data extraction. End-of-life terms and non-English studies were excluded, and publication bias could not be formally tested due to the small number of included studies.

Conclusion

This systematic review has shown that while the strength of evidence for PCC is moderate to poor, there is a small but growing body of evidence which demonstrates that this approach to care reduces symptom burden, readmissions and improves patient activation and quality of life for patients with CHF. Interventions commonly included patient assessment, healthcare professional–patient collaboration, education and patient engagement. Patients’ expertise in their own illness experience was acknowledged [79] as an equal role in the healthcare professional–patient relationship [37]. More research is needed, and future studies should include process measures and quality indicators to help identify the effective components of PCC to inform how policy recommendations can be translated into clinical practice.

References

McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K et al (2012) ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 33:1787–1847. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104

Metra M, Ponikowski P, Dickstein K, McMurray JJV, Gavazzi A, Bergh CH et al (2007) Advanced chronic heart failure: a position statement from the Study Group on Advanced Heart Failure of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 9:684–694

Gastone S, Luciana T, Lorenzo P (2014) Care for older people with heart failure—not just an affair of the heart: brief review. Exp Clin Cardiol 20:3658–3662. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000048893.62841.F7

Dunderdale K, Thompson D, Miles J, Beer S, Furze G (2005) Quality-of-life measurement in chronic heart failure: do we take account of the patient perspective? Eur J Heart Fail 7:572–582. doi:10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.06.006

Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Hole DJ, Capewell S, McMurray JJ (2001) More ‘malignant’ than cancer? Five year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 3:315–322

Jani B, Blane D, Browne S, Montori V, May C, Shippee N et al (2013) Identifying treatment burden as an important concept for end of life care in those with advanced heart failure. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 7:3–7

Boyd KJ, Murray SA, Kendall M, Worth A, Frederick Benton T, Clausen H (2004) Living with advanced heart failure: a prospective, community based study of patients and their carers. Eur J Heart Fail 6:585–591. doi:10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.11.018

Olsson L, Jakobsson Ung E, Swedberg K, Ekman I (2013) Efficacy of person-centred care as an intervention in controlled trials—a systematic review. J Clin Nurs 22:456–465. doi:10.1111/jocn.12039

Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, Goldstein NE, Matlock DD, Arnold RM et al (2012) Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 125:1928–1952. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824f2173

Allen LA, Yager JE, Funk MJ, Levy WC, Tulsky JA, Bowers MT et al (2008) Discordance between patient-predicted and model-predicted life expectancy among ambulatory patients with heart failure. JAMA 299:2533–2542. doi:10.1001/jama.299.21.2533

Stewart GC, Weintraub JR, Pratibhu PP, Semigran MJ, Camuso JM, Brooks K et al (2010) Patient expectations from implantable defibrillators to prevent death in heart failure. J Card Fail 16:106–113. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.09.003

Forman DE, Ahmed A, Fleg JL (2013) Heart failure in very old adults. Curr Heart Fail Rep 10:387–400. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61855-8

Fried TR, O’Leary J, van Ness P, Fraenkel L (2007) Inconsistency over time in the preferences of older persons with advanced illness for life-sustaining treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 55:1007–1014. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01232.x

Krumholz HM, Phillips RS, Hamel MB, Teno JM, Bellamy P, Broste SK et al (1998) Resuscitation preferences among patients with severe congestive heart failure: results from the SUPPORT project. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Circulation 98:648–655

Walsh MN, Bove A, Cross RR, Ferdinand K, Forman D, Freeman A et al (2012) ACCF 2012 health policy statement on patient-centered care in cardiovascular medicine: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Clinical Quality Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 59:2125–2143. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.016

Blom JW, El Azzi M, Wopereis DM, Glynn L, Muth C, van Driel ML (2015) Reporting of patient-centred outcomes in heart failure trials: are patient preferences being ignored? Heart Fail Rev 20:385–392. doi:10.1007/s10741-015-9476-9

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2010) Chronic heart failure: management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. August 2010. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13099/50517/50517.pdf. Accessed 23 Oct 2013

Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M, Rutten FH, McDonagh T, Mohacsi P et al (2009) Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 11:433–443. doi:10.1093/eurjhf/hfp041

Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine (2001) Crossing the quality chasm: a new health chasm for the 21st century. National Academies Press, Washington, DC

The Health Foundation. Patient-centred care. http://www.health.org.uk/areas-of-work/topics/person-centred-care/. Accessed 19 May 2015

The King’s Fund. From vision to action: making patient-centred care a reality: Report (2012) http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/vision-action-making-patient-centred-care-reality. Accessed 19 May 2015

International Alliance of Patients’ Organizations (2007) What is patient-centred healthcare? A review of definitions and principles. http://www.patientsorganizations.org/pchreview. Accessed 4 Nov 2013

Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA (2013) Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 70:351–379. doi:10.1177/1077558712465774

Hudon C, Fortin M, Haggerty JL, Lambert M, Poitras ME (2011) Measuring patients’ perceptions of patient-centered care: a systematic review of tools for family medicine. Ann Fam Med 9:155–164

McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D, Williams PP, Nadler E, Arora NK et al (2011) Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med 72:1085–1095

Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K (2013) What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs 69:4–15

Taylor K (2009) Review: paternalism, participation and partnership—the evolution of patient centeredness in the consultation. Patient Educ Couns 74:150–155. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2008.08.017

Mead N, Bower P (2000) Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med 51:1087–1110

Shaller D (2007) Patient-centred care: What does it take? The Commonwealth Fund. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/usr_doc/Shaller_patient-centeredcarewhatdoesittake_1067.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 2013

Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, MacWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR (1995) Patient-centred medicine: transforming the clinical method. Sage Publications, USA

Michie S, Miles J, Weinman J (2003) Patient-centredness in chronic illness: What is it and does it matter? Patient Educ Couns 51:197–206

Mead N, Bower P (2002) Patient-centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns 48:51–61

Say R, Murtagh M, Thomson R (2006) Patients’ preference for involvement in medical decision making: a narrative review. Patient Educ Couns 60:102–114

Mirzaei M, Aspin C, Essue B, Jeon Y, Dugdale P, Usherwood T et al (2013) A patient-centred approach to health service delivery: improving health outcomes for people with chronic illness. BMC Health Serv Res 13:251. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-251

World Health Organization (2002) Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for action: World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/icccreport/en/. Accessed 24 June 2015

Epping-Jordan JE, Pruitt SD, Bengoa R, Wagner EH (2004) Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care 13:299–305. doi:10.1136/qshc.2004.010744

Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, Lindseth A, Norberg A, Brink E et al (2011) Person-centered care–ready for prime time. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 10:248–251. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008

Charles CA (2003) Shared treatment decision making: What does it mean to physicians? J Clin Oncol 21:932–936. doi:10.1200/JCO.2003.05.057

Stewart M (2001) Towards a global definition of patient centred care. BMJ 322:444–445

World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care: World Health Organisation. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed 28 Aug 2015

Cowie MR (2012) Person-centred care: more than just improving patient satisfaction? Eur Heart J 33:1037–1039. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr354

Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, Jorgenson S, Sadigh G, Sikorskii A et al (2012) Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (12):CD003267. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2

Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Zwarenstein M, Dick J (2001) Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):CD003267. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003267

Duncan E, Best C, Hagen S (2010) Shared decision making interventions for people with mental health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD007297. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007297.pub2

Ramsenthaler C, Kane PM, Siegert RJ, Gao W, Edmonds PM, Schey SA et al (2014) What are the predictors of health-related quality of life and cost in multiple myeloma? A meta-analysis (abstract). Palliat Med 28:631

Downs SH, Black N (1998) The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 52:377–384

Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ (2007) Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res 42:1758–1772. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x

Higgins Julian P T, Green S (2008) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Wiley, Chichester

Rodgers M, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Roberts H, Britten N et al (2009) Testing methodological guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: effectiveness of interventions to promote smoke alarm ownership and function. Evaluation 15:49–73. doi:10.1177/1356389008097871

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339:b2700. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2700

Dudas K, Olsson L, Wolf A, Swedberg K, Taft C, Schaufelberger M et al (2013) Uncertainty in illness among patients with chronic heart failure is less in person-centred care than in usual care. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 12:521–528

Alharbi TS, Carlström E, Ekman I, Olsson L (2014) Implementation of person-centred care: management perspective. J Hosp Adm 3:107–120. doi:10.5430/jha.v3n3p107

Alharbi TSJ, Carlström E, Ekman I, Jarneborn A, Olsson L (2014) Experiences of person-centred care—patients’ perceptions: qualitative study. BMC Nurs 13:28. doi:10.1186/1472-6955-13-28

Evangelista LS, Motie M, Lombardo D, Ballard-Hernandez J, Malik S, Liao S (2012) Does preparedness planning improve attitudes and completion of advance directives in patients with symptomatic heart failure? J Palliat Med 15:1316–1320. doi:10.1089/jpm.2012.0228

Evangelista LS, Liao S, Motie M, de Michelis N, Lombardo D (2014) On-going palliative care enhances perceived control and patient activation and reduces symptom distress in patients with symptomatic heart failure: a pilot study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 13:116–123. doi:10.1177/1474515114520766

Ekman I, Wolf A, Olsson LE, Taft C, Dudas K, Schaufelberger M et al (2012) Effects of person-centred care in patients with chronic heart failure: the PCC-HF study. Eur Heart J 33:1112–1119

Schwarz ER, Baraghoush A, Morrissey RP, Shah AB, Shinde AM, Phan A et al (2012) Pilot study of palliative care consultation in patients with advanced heart failure referred for cardiac transplantation. J Palliat Med 15:12–15

Riegel B, Dickson VV, Hoke L, McMahon JP, Reis BF, Sayers S (2006) A motivational counseling approach to improving heart failure self-care: mechanisms of effectiveness. J Cardiovas Nurs 21:232–241

Dionne-Odom JN, Kono A, Frost J, Jackson L, Ellis D, Ahmed A et al (2014) Translating and testing the ENABLE: CHF-PC concurrent palliative care model for older adults with heart failure and their family caregivers. J Palliat Med 17:995–1004. doi:10.1089/jpm.2013.0680

Delaney C, Apostolidis B (2010) Pilot testing of a multicomponent home care intervention for older adults with heart failure: an academic clinical partnership. J Cardiovas Nurs 25:E27–E40

Brannstrom M, Boman K (2014) Effects of person-centred and integrated chronic heart failure and palliative home care. PREFER: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Heart Fail 16:1142–1151. doi:10.1002/ejhf.151

Shively MJ, Gardetto NJ, Kodiath MF, Kelly A, Smith TL, Stepnowsky C et al (2013) Effect of patient activation on self-management in patients with heart failure. J Cardiovas Nurs 28:20–34. doi:10.1097/JCN.0b013e318239f9f9

Shively M, Kodiath M, Smith TL, Kelly A, Bone P, Fetterly L et al (2005) Effect of behavioral management on quality of life in mild heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 58:27–34

MRC Clinical Trials Unit. What is a clinical trial: Institute of Clinical Trials and Methodology (ICTM). http://www.ctu.mrc.ac.uk/about_clinical_trials/what_is_a_clinical_trial/. Accessed 7 Sept 2015

Evangelista LS, Lombardo D, Malik S, Ballard-Hernandez J, Motie M, Liao S (2012) Examining the effects of an outpatient palliative care consultation on symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in patients with symptomatic heart failure. J Card Fail 18:894–899. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2012.10.019

Schellinger S, Sidebottom A, Briggs L (2011) Disease specific advance care planning for heart failure patients: implementation in a large health system. J Palliat Med 14:1224–1230. doi:10.1089/jpm.2011.0105

Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL (2010) Effect of a disease-specific planning intervention on surrogate understanding of patient goals for future medical treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:1233–1240. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02760.x

Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M (2004) Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 39:1005–1026. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x

Fitzsimons D, Strachan PH (2011) Overcoming the challenges of conducting research with people who have advanced heart failure and palliative care needs. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 11:248–254. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.12.002

McMillan SS, Kendall E, Sav A, King MA, Whitty JA, Kelly F et al (2013) Patient-centered approaches to health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Med Care Res Rev 70:567–596. doi:10.1177/1077558713496318

Fonarow GC, Clyde WY, Thomas HJ (2005) Adherence to heart failure quality-of-care indicators in US hospitals. Arch Intern Med 165:1469–1477

Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall MN (2003) Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 326:816–819

Joyce KE, Lord S, Matlock DD, McComb JM, Thomson R (2013) Incorporating the patient perspective: a critical review of clinical practice guidelines for implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 36:185–197. doi:10.1007/s10840-012-9762-6

Ismail Y, Shorthose K, Nightingale AK (2015) Trainee experiences of delivering end-of-life care in heart failure: key findings of a national survey. Br J Cardiol 22:26–32. doi:10.5837/bjc.2015.008

Uphoff E, Wennekes L, Punt C, Grol R, Wollersheim H, Hermens R et al (2012) Development of generic quality indicators for patient-centered cancer care by using a RAND modified Delphi method. Cancer Nurs 35:29–37. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e318210e3a2

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Chronic Heart Failure Quality Standard: NICE quality standard 9: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. June 2011. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/qs9. Accessed 27 Aug 2015

Farquhar MC, Ewing G, Booth S (2011) Using mixed methods to develop and evaluate complex interventions in palliative care research. Palliat Med 25:748–757. doi:10.1177/0269216311417919

Wakefield BJ, Boren SA, Groves PS, Conn VS (2013) Heart failure care management programs: a review of study interventions and meta-analysis of outcomes. J Cardiovas Nurs 28:8–19. doi:10.1097/JCN.0b013e318239f9e1

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW et al (2000) The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract 49:796–804

Acknowledgments

This paper presents independent research part funded by BuildCARE, part funded by the National Institute for Health Research under the Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (RP-PG-1210-12015 C-CHANGE) and part funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Funding scheme. BuildCARE is supported by Cicely Saunders International (CSI) and The Atlantic Philanthropies, led by King’s College London, Cicely Saunders Institute, Department of Palliative Care, Policy and Rehabilitation, UK. CI: Higginson. We thank all collaborators and advisors including service users. BuildCARE members: Emma Bennett, Francesca Cooper, Barbara A. Daveson, Susanne de Wolf-Linder, Mendwas Dzingina, Clare Ellis-Smith, Catherine J. Evans, Taja Ferguson, Lesley Henson, Irene J. Higginson, Bridget Johnston, Paramjote Kaler, Pauline Kane, Lara Klass, Peter Lawlor, Paul McCrone, Regina McQuillan, Diane Meier, Susan Molony, Sean Morrison, Fliss E. Murtagh, Charles Normand, Caty Pannell, Steve Pantilat, Anastasia Reison, Karen Ryan, Lucy Selman, Melinda Smith, Katy Tobin, Rowena Vohora, Gao Wei. The Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) South London is part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and is a partnership between King’s Health Partners, St. George’s, University London, and St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, CCF, NETSCC, NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme or Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

On behalf of BuildCARE.

Project BuildCARE is about Building Capacity, Access, Rights and Empowerment for patients to improve the palliative care patients receive. Project BuildCARE is supported by Atlantic Philanthropies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kane, P.M., Murtagh, F.E.M., Ryan, K. et al. The gap between policy and practice: a systematic review of patient-centred care interventions in chronic heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 20, 673–687 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-015-9508-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-015-9508-5