Abstract

The first zoeal stage of the endemic southern Atlantic pinnotherid crab Austinixa aidae is described and illustrated based on laboratory-hatched material from ovigerous females collected from the upper burrows of the thalassinidean shrimp Callichirus major at Ubatuba, São Paulo, Brazil. The zoeae of Austinixa species can be distinguished from other pinnotherids and especially from zoeae of the closely related species of Pinnixa by the telson structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, a combination of different tools has helped to elucidate life histories, taxonomy and systematics of decapod crustaceans. One of these tools is the morphological characterization of larvae. Larvae are recognized as a significant source of independent information for phylogenetic analyses. Considering the large number of species described worldwide by their adult morphologies, much effort is still needed to describe larval morphologies. This is particularly evident in the families of the Brachyura that represent almost half the known decapod species, because analyses of their systematic relationships are partly based on zoeal characters (Rice 1980; Ng and Clark 2000; Marques and Pohle 2003; Anger 2001, 2006).

Crabs of the family Pinnotheridae De Haan, 1833, with currently more than 300 species distributed among about 52 genera (Ng et al. 2008), are one of the little-known groups in terms of larval morphology. This probably relates to the small size of these crabs and their intriguing life cycle. They typically show complex symbiotic relationships with various invertebrate hosts. In addition, the phylogenetic position of some members is still unclear and under active discussion (Palacios-Theil et al. 2009).

Members of the polyphyletic genus Austinixa Heard and Manning 1997 (sensu Palacios-Theil et al. 2009) currently comprise nine described and two still undescribed species, most of which occurring in the western Atlantic and the Caribbean; only Austinixa felipensis (Glassel 1935) is found on the Pacific coast (Heard and Manning 1997; Coelho 1997, 2005; Harrison 2004; Palacios-Theil et al. 2009). In only three of these species have the larval stages been completely or partially been described (Table 1).

In the present study, we describe and illustrate the morphology of the zoea I of Austinixia aidae (Righi 1967) from laboratory-hatched material. The results are compared with those from larvae of other species of Pinnotheridae (sensu Ng et al. 2008) previously described for the South Atlantic, in order to offer data for future studies on the phylogeny and biogeography of the group as well as for plankton analyses.

Materials and methods

Ovigerous females of Austinixa aidae were collected in November 2004 and July 2009 in the intertidal of a semi-protected and dissipative beach composed by fine sands at Perequê-Açu, Ubatuba Bay, State of São Paulo, Brazil (23°24′59.99″S, 45°03′17.13″W). Crabs were collected with suction pumps from galleries of Callichirus major and separated from the sand with a 1-mm mesh sieve.

Species identification was confirmed on the basis of morphological characters from available references (Manning and Felder 1989; Heard and Manning 1997). Additionally, and because of the complex taxonomy of this genus, tissue samples were taken from the animals for molecular analysis of a partial fragment of the 16S rDNA gene, in order to confirm the species identification. DNA extraction, amplification, sequencing protocols and phylogenetic analysis followed Schubart et al. (2000), with modifications as in Mantelatto et al. (2007, 2009) and Palacios-Theil et al. (2009).

Ovigerous females were transported to the laboratory in an insulated box containing water from the site of collection. In the laboratory, the animals were isolated in aquaria with oxygenated sea water at a salinity of 34 and constant temperature (24 ± 1°C) until hatching. Newly hatched zoeae were fixed in a 1:1 mixture of 70% ethyl alcohol and glycerin.

The first zoeae were dissected for detailed examination under a stereoscope and mounted on semi-permanent slides. Morphological characters were studied with Leica DM 1000® and Zeiss Axioskop® compound microscopes attached to a personal computer using an Axiovision® image analysis system and a drawing tube, respectively. A minimum of 10 specimens was used in the descriptions and measurements. The sequence of the zoeal description is based on the malacostracan somite plan, from anterior to posterior, following literature recommendations (see Clark et al. 1998; Pohle et al. 1999). Setae terminology follows Garm (2004). Long natatory setae on the first and second maxilliped are drawn truncated in Fig. 2. Dimensions measured on each zoea were: rostro-dorsal length (rdl), as the distance between the tips of the dorsal and rostral spines; carapace length (cl), measured from the base of the rostral spine (between the eyes) to the most posterior margin of the carapace; dorsal spine length (dsl), from the base to the tip of the dorsal spine; rostral spine length (rsl), from the base (between the eyes) to the tip of the rostral spine; and lateral spine length (lsl), from the base to the tip of the lateral spine.

The females and zoeal stages of Austinixa aidae were deposited as voucher specimens in the Crustacean Collection of the Department of Biology (CCDB), Faculty of Philosophy, Science and Letters of Ribeirão Preto (FFCLRP), University of São Paulo (USP), and allocated registration numbers CCDB 2643 to 2648, 2657 and 2658.

Results

The mtDNA obtained from ovigerous females matched 100% with the sequence from the nucleotide region of the 16S rDNA that was studied previously (Genbank EU934966) by Palacios-Theil et al. (2009), confirming the species’ correct identification. During the culture, we obtained two different hatches from a single female (on 10 Nov 2004 and 8 Dec 2004), showing a pattern of multiple hatching without additional copula.

Size—rdl: 0.95 ± 0.002 mm; cl: 0.036 ± 0.003 mm; dsl: 0.023 ± 0.003 mm; rsl: 0.036 ± 0.002 mm; lsl: 0.016 ± 0.002 mm.

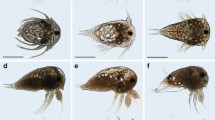

Morphology—Carapace (Fig. 1a–b): Globose, smooth, without tubercles. Dorsal spine long, slightly curved. Rostral spine present and straight, longer than dorsal spines. Lateral spines well developed, long, ventrally deflected. One pair of posterodorsal simple setae, posterior and ventral margins without setae. Eyes sessile.

Antennule (Fig. 1d): Uniramous; endopod absent; exopod unsegmented, with two long stout aesthetascs and one simple seta, all terminal.

Antenna (Fig. 1e): Protopod well developed, length less than one-third of that of the rostral spine, with two rows of minute spines along most of protopod length except the base. Exopod present as a small bud with a terminal simple seta.

Mandibles (Fig. 1c): Right molar with short teeth and left molar with one tooth, confluent with incisor process. Endopod palp absent.

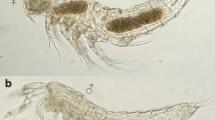

Maxillule (Fig. 2a): Coxal endite with 3 plumodenticulate setae and 1 plumose seta. Basial endite with 2 plumodenticulate and 2 cuspidate setae. Endopod 2-segmented, with 4 plumodenticulate setae (2 subterminal + 2 terminal) on distal segment.

Maxilla (Fig. 2b): Coxal endite slightly bilobed, with 4 + 1 plumose setae. Basial endite bilobed, with 4 + 4 plumodenticulate setae. Endopod not bilobed, unsegmented, with 3 (2 + 1) plumodenticulate terminal setae and microtrichia on both proximal and distal margins. Exopod (scaphognathite) margin with 4 plumose setae and a long setose posterior process.

First maxilliped (Fig. 2c): Coxa with one simple setae. Basis with 10 simple setae arranged 2, 2, 3, 3. Endopod 5-segmented with 2, 2, 1, 2, 5 (1 subterminal + 4 terminal) plumose setae, respectively. Exopod unsegmented, with 4 long terminal plumose natatory setae.

Second maxilliped (Fig. 2d): Coxa without setae. Basis with 4 plumose setae arranged 1, 1, 1, 1. Endopod 2-segmented, with 0, 5 (1 subterminal + 4 terminal) plumose setae. Exopod unsegmented, with four long terminal plumose natatory setae.

Third maxilliped: absent.

Pereiopods: absent.

Pleon (Fig. 1f): Five somites present. Somites 2–3 with 1 pair of lateral processes. Somite 5 laterally expanded, overlapping the telson. Somites 2–5 with 1 pair of posterodorsal setae. Pleopods absent.

Telson (Fig. 1f): Bifurcated, with three pairs of stout spinulate setae on posterior margin separated by a prominent median subtriangular lobe. Each furca long, with a small lateral spine and with two rows of spinules.

Discussion

In the western Atlantic, the family Pinnotheridae encompasses more than 30 named species (Melo 1996; Coelho 1997, 2005), but to date, the larval stages have been described completely or partially for only 16 pinnotherids (see Table 1). From 1996 to the present, the rate of description of new larval stages of pinnotherids lagged behind that of other brachyuran groups, probably due to the difficulties in collecting ovigerous females and in rearing their small zoeae. We are probably far from knowing the real diversity of larval forms that this family may present.

Taking into account the few descriptions of pinnotherid larvae available, the morphological characters of the zoea I of A. aidae are compared with those of previously described zoeae of the genera Austinixa and Pinnixa (Table 1), assuming the hypothesis of a close phylogenetic proximity of the two genera (Palacios-Theil et al. 2009).

Although the zoeae of the eight species of Austinixa and Pinnixa are basically similar in morphology, zoeae of Austinixa can be easily distinguished from those of Pinnixa by the telson structure. However, there is one exception: Pinnixa chaetopterana has the posterior median lobe on the telson that characterizes Austinixia zoeae and is absent in all other known species of Pinnixa. This interesting relationship of P. chaetopterana with Austinixa was also detected in a recent molecular phylogeny of the group, where P. chaetopterana together with P. sayana and P. rapax occupied a basal position in the Austinixa clades (Palacios-Theil et al. 2009; Fig. 1, clades IA, IB, IC, p. 464). To date, there are no data available on larvae of P. rapax, but P. sayana larvae lack the median lobe like all other known larvae of Pinnixa except for P. chaetopterana. Therefore, at this point, the interpretation of this feature with respect to the phylogenetic position of these species is unclear, although the polyphyly of Pinnixa sensu lato has been clearly pointed out recently (Palacios-Theil et al. 2009). In any case, the known zoea stages of the congeneric species of Pinnixa of the western and eastern Pacific, P. tumida, P. rathbuni and P. longipes (Konishi et al. 1988; Sekiguchi 1978; Bousquette 1980) do not have the median lobe on the posterior margin of telson either. Therefore, this character seems to be appropriate to distinguish the zoeae of Pinnixa from the rest of the Pinnothereliinae.

A comparison between larvae of A. aidae and the previously described zoeae I of other Austinixa species must remain restricted to A. cristata and A. bragantina. The published data on A. patagoniensis is but a small lateral view of the zoea II which only allows us to confirm the presence of the median lobe on the posterior margin of the telson (Boschi 1981).

The setation pattern of the mouthparts seems to be constant through the complete zoeal phase in all these species: 2, 2, 3, 3 and 1, 1, 1, 1 for the first and second maxilliped, respectively. Where deviations from this pattern were reported (such as 2, 3, 1, 2 and 1, 1, 1, respectively, for A. bragantina; Lima 2009), these findings require confirmation. The same applies to another observation by Lima (2009), the absence of lateral spines on the telson of the zoea I in A. bragantina.

Therefore, differences between the zoea I of Austinixa larvae are probably only evident in the cephalothorax and the pleon armature. Austinixa cristata zoea I (Dowds 1980) can be differentiated by the similar lengths of the dorsal and rostral spines; in A. bragantina and A. aidae, the rostral spine is clearly longer than the dorsal. Regarding the pleon differences, we found that A. aidae can be separated from A. bragantina and A. cristata by the presence of lateral spines on the telson. However, in A. bragantina, these spines have been reported for the zoea II and subsequent stages (Lima 2009) and thus might have been overlooked in the zoea I. We also found that A. cristata has the longest furcal arms (from the telson base) compared with A. aidae and A. bragantina.

Adult morphological characters are particularly difficult to use in inferring evolutionary relationships among species of Austinixa (Harrison 2004). In addition, apparent convergent evolution and/or stabilizing selection due to commensal lifestyles makes it difficult to find ‘‘good’’ morphological characters for phylogenetic studies (Zmarzly 1992).

Unfortunately, the larvae of A. bragantina were not archived in a zoological collection, and no additional material is available to double-check the analysis (J. Lima, personnel communication). Thus, the possibility remains that there are no real morphological differences between the zoea I of A. bragantina and A. aidae. Addition analyses of the morphology and DNA of adults and larvae of A. bragantina would be welcomed and necessary to reassess the treatment of A. bragantina as a valid species.

Our study evidences some important differences in the morphology of Austinixa larvae, which may reflect a high morphological plasticity in this genus. The outcome of the present study should encourage future studies of the larval morphology in congeners. Moreover, our findings confirm the need for a revised classification based on both molecular analyses and re-evaluations of the larval and adult morphology (Bolaños et al. 2004).

References

Anger K (2001) The biology of decapod crustacean larvae. Crust Issues 14:1–420

Anger K (2006) Contributions of larval biology to crustacean research: a review. Invert Reprod Develop 49:175–205

Bolaños J, Cuesta JA, Hernández G, Hernández J, Felder DL (2004) Abbreviated larval development of Tunicotheres moseri (Rathbun, 1918) (Decapoda: Pinnotheridae), a rare case of parental care among brachyuran crabs. Sci Mar 68:373–384

Bolaños J, Rivero W, Hernández J, Magán I, Hernández G, Cuesta JA, Felder DL (2005) Abbreviated larval development of the pea crab Orthotheres barbatus (Decapoda: Brachyura: Pinnotheridae) reared under laboratory conditions, with notes on larval characters of the Pinnotherinae. J Crust Biol 25:500–506

Boschi EE (1981) Larvas de Crustacea Decapoda. In: Boltovskoy D (ed) Atlas del zooplancton del atlántico sudoccidental. Contribuciones del Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones y Desarollo Pesquero No. 378, vol 38, pp 699–757

Bousquette GD (1980) The larval development of Pinnixa longipes (Lockington, 1877) (Brachyura: Pinnotheridae) reared in the laboratory. Biol Bull 159:592–605

Clark PF, Calazans DK, Pohle GW (1998) Accuracy and standardization of brachyuran larval descriptions. Invert Reprod Develop 33:127–144

Coelho PA (1997) Revisão do gênero Pinnixa White, 1846, no Brasil (Crustacea, Decapoda, Pinnotheridae). Trabs Oceanog Univ Fed Pernambuco 25:163–193

Coelho PA (2005) Descrição de Austinixa bragantina sp. nov. (Crustacea, Decapoda, Pinnotheridae), do litoral do Pará, Brasil. Revta Bras Zool 22:552–555

Costlow JD Jr, Bookhout CG (1966) Larval stages of the crab, Pinnotheres maculatus under laboratory conditions. Chesapeake Sci 7:157–163

Dowds RE (1980) The crab genus Pinnixa in a North Carolina estuary: identification of larvae, reproduction, and recruitment. PhD Thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, pp 1–189

Garm A (2004) Revising the definition of the crustacean seta and setal classification systems based on examinations of the mouthpart setae of seven species of decapods. Zool J Linn Soc 142:233–252

Gutiérrez-Martinez J (1971) Notas biológicas sobre Pinnaxodes chilensis (Milne Edwards) y descripción de su primera zoea. Mus Nac Hist Nat Not Mens 15:3–10

Harrison JS (2004) Evolution, biogeography, and the utility of mitochondrial 16S and COI genes in phylogenetic analysis of the crab genus Austinixa (Decapoda: Pinnotheridae). Mol Phylog Evol 30:743–754

Heard RL, Manning RB (1997) Austinixa, a new genus of pinnotherid crab (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura), with the description of A. hardyi, a new species from Tobago, West Indies. Proc Biol Soc Wash 110:393–398

Hyman OW (1925) Studies on larvae of crabs of the family Pinnotheridae. Proc US Natl Mus 64:1–9 VI plates

Konishi K, Kiyosawa S, Maruyama S (1988) The larval development of Pinnixa tumidae Stimpson, 1858 under laboratory conditions (Crustacea: Decapoda: Pinnotheridae), with notes on larval characters in the genus Pinnixa. Zool Sci 5(6):1336

Lima JF (2009) Larval development of Austinixa bragantina (Crustacea: Brachyura: Pinnotheridae) reared in the laboratory. Zoologia 26:143–154

Lima JF, Abrunhosa F, Coelho PA (2006) The larval development of Pinnixa gracilipes Coelho (Decapoda, Pinnotheridae) reared in the laboratory. Revta Bras Zool 23:480–489

Manning RB, Felder DL (1989) The Pinnixa cristata complex in the western Atlantic, with descriptions of two new species (Crustacea: Decapoda: Pinnotheridae). Smithson Contrib Zool 473:1–26

Mantelatto FL, Robles R, Felder DL (2007) Molecular phylogeny of the western Atlantic species of the genus Portunus (Crustacea, Brachyura, Portunidae). Zool J Linn Soc 150:211–220

Mantelatto FL, Robles R, Schubart CD, Felder DL (2009) Chapter 29. Molecular phylogeny of the genus Cronius Stimpson, 1860, with reassignment of C. tumidulus and several American species of Portunus to the genus Achelous De Haan, 1833 (Brachyura: Portunidae). In: Martin JW, Crandall KA, Felder DL (eds) Crustacean issues: decapod crustacean phylogenetics. Taylor & Francis/CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 567–579

Marques F, Pohle GW (1996) Complete larval development of Clypeasterophilus stebbingi (Decapoda, Brachyura, Pinnotheridae) and a comparison with other species within the Dissodactylus complex. Bull Mar Sci 58:165–185

Marques F, Pohle GW (2003) Searching for larval support for majoid families (Crustacea: Brachyura) with particular reference to Inachoididae Dana, 1851. Invert Reprod Develop 43:71–82

Melo GAS (1996) Manual de identificação dos Brachyura (Caranguejos e Siris) do litoral brasileiro. Plêiade/FAPESP, São Paulo

Ng PKL, Clark PF (2000) The eumedonid file: a case study of systematic compatibility using larval and adult characters (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura). Invert Reprod Develop 38:225–252

Ng PKL, Guinot D, Davie PJF (2008) Systema brachyurorum: Part 1. An annotated checklist of extant brachyuran crabs of the world. Raffles Bull Zool 17:1–286

Palacios-Theil E, Cuesta JA, Campos E, Felder DL (2009) Chapter 23. Molecular genetic re-examination of subfamilies and polyphyly in the Family Pinnotheridae (Crustacea: Decapoda). In: Martin JW, Crandall KA, Felder DL (eds) Crustacean issues: decapod crustacean phylogenetics. Taylor & Francis/CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 423–442

Pohle GW, Telford M (1981) The larval development of Dissodactylus crinitichelis Moreira, 1901 (Brachyura: Pinnotheridae) in the laboratory culture. Bull Mar Sci 31:753–773

Pohle GW, Mantelatto FL, Negreiros-Fransozo ML, Fransozo A (1999) Larval Decapoda (Brachyura). In: Boltovskoy D (ed) South atlantic zooplankton. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, pp 1281–1351

Rice AL (1980) Crab zoeal morphology and its bearing on the classification of the Brachyura. Trans Zool Soc Lond 25:271–424

Roberts MH Jr (1975) Larval development of Pinnotheres chamae reared in the laboratory. Chesapeake Sci 16:242–252

Sandifer PA (1972) Morphology and ecology of Chesapeake Bay decapod crustacean larvae. PhD Thesis, University of Virginia, pp 1–532

Schubart CD, Neigel JE, Felder DL (2000) Use of the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene for phylogenetic and population studies of Crustacea. Crust Issues 12:817–830

Sekiguchi H (1978) Larvae of a pinnotherid crab, Pinnixa rathbuni Sakai. Proc Jap Soc Syst Zool 15:36–46

Zmarzly DL (1992) Taxonomic review of pea crabs in the genus Pinnixa (Decapoda: Brachyura: Pinnotheridae) occurring on the California shelf, with descriptions of two new species. J Crust Biol 12:677–713

Acknowledgments

FLM is grateful to CNPq for a research fellowship (Proc. 301359/2007-5). Special thanks are due to Alline Gatti for her assistance with the first drawings and dissection, to Danilo Espósito and Douglas Peiró for their help during the field collection and the first laboratory experiments, to Jô Lima for additional information on larvae of A. bragantina and to Ernesto Campos and handling editor for suggestions and contributions toward the improvement of this paper. All experiments conducted in this study complied with current applicable state and federal laws of Brazil (DIFAP/IBAMA No. 122/05). This paper was written as part of a cooperative project between the University of São Paulo (FFCLRP) (Brazil) and ICMAN-CSIC (Spain). Dra. Janet Reid (JWR Associates, USA) revised the English text.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by H.-D. Franke.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mantelatto, F.L., Cuesta, J.A. Morphology of the first zoeal stage of the commensal southwestern Atlantic crab Austinixa aidae (Righi 1967) (Brachyura: Pinnotheridae), hatched in the laboratory. Helgol Mar Res 64, 343–348 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-010-0189-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-010-0189-0