Abstract

Introduction

To date, there are no prospective randomized studies that compare the outcome of endoscopic repair of primary versus recurrent inguinal hernias. It is therefore now attempted to answer that key question on the basis of registry data.

Patients and methods

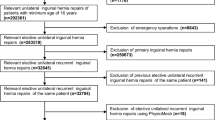

In total, 20,624 patients were enrolled between September 1, 2009, and April 31, 2013. Of these patients, 18,142 (88.0 %) had a primary and 2482 (12.0 %) had a recurrent endoscopic repair. Only patients with male unilateral inguinal hernia and with a 1-year follow-up were included. The dependent variables were intra- and postoperative complications, reoperations, recurrence, and chronic pain rates. The results of unadjusted analyses were verified via multivariable analyses.

Results

Unadjusted analysis did not reveal any significant differences in the intraoperative complications (1.28 vs 1.33 %; p = 0.849); however, there were significant differences in the postoperative complications (3.20 vs 4.03 %; p = 0.036), the reoperation rate due to complications (0.84 vs 1.33 %; p = 0.023), pain at rest (4.08 vs 6.16 %; p < 0.001), pain on exertion (8.03 vs 11.44 %; p < 0.001), chronic pain requiring treatment (2.31 vs 3.83 %; p < 0.001), and the recurrence rates (0.94 vs 1.45 %; p = 0.0023). Multivariable analysis confirmed the significant impact of endoscopic repair of recurrent hernia on the outcome.

Conclusion

Comparison of perioperative and 1-year outcome for endoscopic repair of primary versus recurrent male unilateral inguinal hernia showed significant differences to the disadvantage of the recurrent operation. Therefore, endoscopic repair of recurrent inguinal hernias calls for particular competence on the part of the hernia surgeon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The proportion of recurrences in the National Swedish Hernia Registry is 11.2 % [1]. Female sex, direct inguinal hernias at the time of the primary procedure, operation for a recurrent inguinal hernia, and smoking are significant risk factors for recurrence after inguinal hernia surgery [2]. In five meta-analyses, the outcome of open repair was compared with that of endoscopic repair of recurrent inguinal hernias [3–7]. The last meta-analysis published and which included 1311 patients from six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and five comparative studies [7] showed that the laparoscopic technique for repair of recurrent inguinal hernia was associated with less wound infection and a faster recovery to normal activity, whereas other complication rates, including the re-recurrence rate, were comparable between the open and the endoscopic approach. Laparoscopic and open procedures could be performed with equal operation time.

On the basis of the meta-analyses, the European Hernia Society recommends endoscopic inguinal hernia techniques for recurrent hernias after conventional open repair [8]. Likewise, the International Endohernia Society recommends, with a high level of evidence, TEP and TAPP for repair of recurrent hernia as the preferred alternative to tissue repair and to the Lichtenstein repair after prior anterior repair [9]. In the Consensus Development Conference of the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery, TEP and TAPP are preferred in patients with a recurrent groin hernia after open repair. Repeat endoscopic repair is only feasible when the surgeon has a high level of experience in repeat endoscopic groin hernia repair [10].

To date, there is only one prospective study, published in German language, with 338 patients comparing endoscopic repair of primary and recurrent inguinal hernias in TEP technique [11]. In the TEP repair group of recurrent inguinal hernias, a higher incidence of injury to the peritoneum and a higher occurrence of bleeding from the epigastric vessels were observed (p = 0.03). The postoperative complication rate was identical in the two groups, amounting to 5.1 and 5.7 %, respectively. No differences were found between the two groups on 1-year follow-up.

By analyzing data from the Herniamed Registry [12], this paper now performs such a comparison in order to get a better estimate of the perioperative and 1-year outcome of repair of primary versus recurrent hernia on the basis of a large patient sample size.

Patients and methods

The Herniamed Registry is a multicenter, internet-based Hernia Registry [12] into which 425 participating hospitals and surgeons engaged in private practice (Herniamed Study Group) had entered data prospectively on their patients who had undergone hernia surgery. All postoperative complications occurring up to 30 days after surgery are recorded. On 1-year follow-up, postoperative complications are once again reviewed when the general practitioner and patient complete a questionnaire. This present analysis compares the prospective data collected for all male patients with a minimum age of 16 years, who had undergone elective primary or recurrent unilateral inguinal hernia repair using either transabdominal preperitoneal patch plasty (TAPP) or total extraperitoneal patch plasty (TEP).

In total, 20,624 patients were enrolled between September 1, 2009, and August 31, 2013. Of these patients, 18,142 (88.0 %) had a primary endoscopic repair and 2482 (12.0 %) had a recurrent endoscopic repair. All the patients had to have a 1-year follow-up (follow-up rate: 100 %).

The demographic and surgery-related parameters included age (years), BMI (kg/m2), ASA classification (I, II, III, IV) as well as EHS classification (hernia type: medial, lateral, femoral, scrotal. Defect size: grade I = < 1.5 cm, grade II = 1.5–3 cm, grade III > 3 cm) [13], and general risk factors (nicotine, COPD, diabetes, cortisone, immunosuppression, etc.). Risk factors were dichotomized, i.e., ‘yes’ if at least one risk factor is positive and ‘no’ otherwise.

The dependent variables were intra- and postoperative complication rates, number of reoperations due to complications as well as the 1-year results (recurrence rate, pain at rest, pain on exertion, and pain requiring treatment).

All analyses were performed with the software SAS 9.2 (SAS institute Inc. Cary, NY, USA) and intentionally calculated to a full significance level of 5 %, i.e., they were not corrected in respect of multiple tests, and each p value ≤0.05 represents a significant result. To discern differences between the groups in unadjusted analyses, Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical outcome variables, and the robust t test (Satterthwaite) for continuous variables.

To rule out any confounding of data caused by different patient characteristics, the results of unadjusted analyses were verified via multivariable analyses in which, in addition to primary or recurrent operation, other influence parameters were simultaneously reviewed.

To identify influence factors in multivariable analyses, the binary logistic regression model for dichotomous outcome variables was used. Estimates for odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95 % confidence interval based on the Wald test were given. For influence variables with more than two categories, one of the latter forms was used in each case as reference category. For age (years) the 10-year OR estimate and for BMI (kg/m2) the 5-point OR estimate were given. Results are presented in tabular form, sorted by descending impact.

Results

Unadjusted analysis

In the endoscopic recurrent operation group, the recurrent operation was performed for n = 1528/2482 (61.6 %) patients following the open suture technique, for n = 718/2482 (28.9 %) after open mesh repair, and for n = 233/2.482 (9.4 %) following laparoscopic mesh repair. In terms of age, those patients with recurrent operations were significantly older (p < 0.001). No significant difference was noted in BMI (Table 1).

The unadjusted tests aimed at discerning any relationship between operation type (primary vs recurrent operation), and the categorical influence variables showed a highly significant relationship between the ASA classification, hernia size, and all EHS classifications (in each case, p < 0.001) (Table 2). More recurrent operations were associated with higher ASA classifications, e.g., ASA III/IV: 17.1 vs 12.3 % as well as medial (49.8 vs 36.2 %) and femoral (3.3 vs 1.8 %) EHS classifications. On the other hand, primary operations were associated with larger defect sizes, e.g., EHS grade III: 20.8 vs 17.3 % as well as with a greater number of lateral (74.0 vs 59.2 %) and scrotal (2.8 vs 1.3 %) EHS classifications.

As regards the risk factors, global analysis, i.e., at least one risk factor, likewise revealed a highly significant difference between the primary and recurrent operation (p < 0.001). Of patients with recurrences, 30.1 % had at least one risk factor, while this applied to 25.3 % of patients with a primary inguinal hernia.

As regards the individual risk factors too, the corresponding rates were sometimes significantly higher for recurrent operations (Table 2).

No difference was observed in the intraoperative complication rates between endoscopic primary and recurrent operations (Table 3). Postoperative complications, complication-related reoperations as well as the recurrence rate, pain at rest, pain on exertion, and pain requiring treatment on 1-year follow-up were significantly higher after endoscopic recurrent operations than after endoscopic primary operation (Table 3).

Multivariable analysis

The results of multivariable analysis of the postoperative complication rates are illustrated in Table 4 (model matching p < 0.001). The probability of postoperative complications was essentially determined by the scrotal EHS classification (p < 0.001). Likewise, a highly significant impact was exerted by hernia defect sizes, age, BMI, and lateral EHS classification on onset of postoperative complications (in each case, p < 0.001). Scrotal EHS classification [OR 2.558 (1.845; 3.548)], larger defect size [II vs I: OR 1.603 (1.202; 2.138); III vs I: OR 2.323 (1.699; 3.177)], and higher age [10-year OR 1.133 (1.067; 1.204)] were conducive to onset of postoperative complications (Table 4).

On the other hand, a 5-point higher BMI [5-point OR 0.782 (0.691; 0.884)] as well as a lateral EHS classification [OR 0.645 (0.499; 0.834)] reduced the risk of postoperative complications. Likewise, a medial EHS classification (OR 0.658 [0.512; 0.845; p = 0.001]) and primary operations [OR 0.797 (0.638; 0.995); p = 0.045] significantly reduced the risk of onset of a postoperative complication. With an overall prevalence of 3.3 %, there would thus be 29 postoperative complications for every 1000 primary operations compared with 36 postoperative complications for every 1000 recurrent operations.

The results of analysis of the reoperation rate are shown in Table 5 (model matching: p < 0.001). Here, too, scrotal EHS classification emerged as the strongest influence factor. The reoperation risk was significantly increased for scrotal EHS classification [OR 2.266 (1.204; 4.264); p = 0.011]. A 5-point higher BMI was shown to be preventive here with regard to the reoperation rate [5-point OR 0.745 (0.589; 0.942); p = 0.014]. Likewise, primary operation significantly reduced the reoperation risk [OR 0.630 (0.428; 0.927); p = 0.019]. With an overall reoperation rate of 0.9 %, that thus corresponds to around seven reoperations for every 1000 patients with primary operation compared with 11 reoperations for every 1000 patients with a recurrent operation.

Conversely, larger hernia defect sizes [III vs I: OR 1.970 (1.130; 3.436); p = 0.021] as well as a higher age [10-year OR 1.122 (1.001; 1.257); p = 0.047] significantly increased the reoperation risk.

Table 6 illustrates the results of multivariable analysis of the parameters implicated in onset of recurrences on 1-year follow-up (model matching: p < 0.001). Here, the BMI emerged as the strongest influence factor (p = 0.004). A 5-point higher BMI increased the recurrence rate [5-point OR 1.304 (1.089; 1.562)]. Likewise, medial EHS classification significantly increased the recurrence rate on follow-up [OR 1.682 (1.144; 2.471); p = 0.008]. The ASA status, too, had a significant effect on the recurrence rate on follow-up, something which, however, cannot be unequivocally specified in the categories (p = 0.039). Conversely, for a primary operation only a tendentially predictive effect could be demonstrated [OR 0.710 (0.491; 1.027); p = 0.069].

The results of multivariable analysis of pain at rest on 1-year follow-up are summarized in Table 7 (model matching: p < 0.001). That was highly significantly influenced by the operation type (p < 0.001). A primary operation reduced the risk of pain at rest [OR 0.661 (0.550; 0.794)]. With an overall prevalence of 4.3 %, that corresponds to 35 patients with pain at rest for every 1000 primary operations compared with 51 patients with pain at rest for patients with recurrent operations.

Likewise, BMI and hernia defect size had a highly significant impact (in each case, p < 0.001). A higher BMI increased the risk of pain at rest [5-point OR 1.284 (1.172; 1.406)]. On the other hand, a larger defect size reduced the risk of pain [II vs I: OR 0.666 (0.561; 0.791); III vs I: OR 0.551 (0.437; 0.694)].

Equally, pain on exertion on follow-up, whose results are summarized in Table 8 (model matching: p < 0.001), was highly significantly influenced by the operation type (p < 0.001).

Conduct of a primary operation was associated with highly significantly less pain on exertion [OR 0.667 (0.581; 0.765)]. With an overall prevalence of 8.4 %, that corresponds to onset of pain on exertion in around 68 out of every 1000 patients with primary operations compared with 99 out of every 1000 patients with recurrent operations.

Likewise, age, hernia defect size, and BMI exerted a highly significant impact on pain on exertion (in each case, p < 0.001). In this regard, the probability of occurrence of pain on exertion declined with higher age [10-year OR 0.834 (0.804; 0.865)] as well as in the presence of larger hernias [II vs I: OR 0.721 (0.634; 0.819); III vs I: OR 0.610 (0.514; 0.724)]. Conversely, a 5-point higher BMI increased the risk of pain [5-point OR 1.175 (1.096; 1.259)].

The results of analysis of pain requiring treatment are shown in Table 9 (model matching: p < 0.001). There is hardly any difference between these results and those obtained for pain on exertion. Here, too, the hernia defect size, BMI, operation type, and age played a highly significant role (in each case, p < 0.001). A larger defect size [II vs I: OR 0.502 (0.408; 0.619); III vs I: OR 0.404 (0.299; 0.545)], primary operation [OR 0.605 (0.480; 0.763)], and older age [10-year OR 0.880 (0.825; 0.940)] reduced the risk of chronic pain requiring treatment. Conversely, the risk of pain was increased by a 5-point higher BMI [5-point OR 1.405 (1.257; 1.570)].

With an overall prevalence of 2.5 %, the impact of the operation type on onset of pain requiring treatment would mean that some 19 out of every 1000 patients with primary operation suffer from pain requiring treatment compared to 31 out of every 1000 patients with recurrent operation.

Analysis of the intraoperative complications (model matching: p > 0.001) showed that only for medial EHS classification was a significant relationship identified. Here, the risk of intraoperative complications was reduced for patients with medial EHS classification [OR 0.564 (0.372; 0.855)]. No significant impact was identified for any of the other parameters.

Discussion

The heterogeneous nature of recurrent hernias makes RCTs in this field difficult and time-consuming, particularly when the previous repair has to be taken into consideration [1]. Accordingly, to date there are no RCTs comparing the outcome of endoscopic repair of primary versus recurrent hernias. Large hernia registries are a valuable way of obtaining information on recurrent groin hernia surgery [1].

In this present analysis of data from the Herniamed Registry [12], the outcome of endoscopic repair of 18,142 primary hernias was compared with that of 2482 recurrent inguinal hernias on the basis of the perioperative complications and the 1-year follow-up. To enhance comparability, only male unilateral inguinal hernias for which the corresponding 1-year follow-up information was available were analyzed.

Based on the Guidelines der European Hernia Society [8], the International Endohernia Society [9], and the European Association of Endoscopic Surgery [10], endoscopic repair of recurrent inguinal hernias was performed in 61.6 % of cases following previous open suture technique, in 28.9 % following previous open mesh repair, and only in 9.4 % of cases after previous endoscopic mesh repair.

The potential risk factors identified for onset of recurrences following inguinal hernia surgery were high age, higher BMI, smoking, hernia type, and certain diseases (COPD, diabetes mellitus, aortic aneurysm, immunosuppression, etc.) [2].

Certain conclusions can be drawn, with regard to onset of inguinal hernia recurrences, from the proportion of these risk factors implicated in the two comparison groups. For example, this present analysis did not identify any significant difference between the two comparison groups in terms of mean BMI, proportion of smokers, and immunosuppressed patients. However, significant differences were found between the primary and recurrent inguinal hernia groups with regard to age, proportion of patients with a history of COPD, diabetes mellitus, and aortic aneurysm as well as patients who had to take platelet aggregation inhibitors.

On comparing the perioperative outcome of endoscopic repair of primary versus recurrent male unilateral inguinal hernias, no significant difference was discerned with regard to the intraoperative complications (1.28 vs 1.33 %; p = 0.849), but definitely were for the postoperative complications (3.20 vs 4.03 %; p = 0.036) and the complication-related reoperation rates (0.84 vs 1.33 %; p = 0.023). Likewise, multivariable analysis confirmed that the recurrent operation, in addition to scrotal hernia, larger defect size, higher age, and higher BMI, had a negative impact on postoperative complications. That was also true for the complication-related reoperation rates. And while the differences between the two groups are significant in view of the large sample size, the absolute values clearly show that even recurrent hernias can be operated on with a very low perioperative complication rate when using an endoscopic repair technique. Accordingly, patients should be informed in an informed consent discussion that the risk associated with endoscopic inguinal hernia repair is higher for a recurrent operation compared with a primary operation.

Equally, significant differences were seen for all criteria in the results of 1-year follow-up for endoscopic primary repair of primary versus recurrent male unilateral inguinal hernias. For example, significant differences were noted in the recurrence rates (0.94 vs 1.45 %; p = 0.023), pain at rest (4.08 vs 6.16 %; p < 0.001), pain on exertion (8.03 vs 11.44 %; p < 0.001), and chronic pain rate requiring treatment (2.31 vs 3.83 %; p < 0.001). However, multivariable analysis identified the significant impact exerted by the recurrent operation on the recurrence rate only as a trend. Rather, a higher BMI value, higher ASA classification, and medial hernia classification were responsible for re-recurrence.

Multivariable analysis identified the significantly negative impact exerted by a recurrent operation on pain at rest, pain on exertion, and pain requiring treatment. Furthermore, a higher BMI value, smaller defect size, and younger age were implicated in onset of pain after endoscopic inguinal hernia repair.

The present data thus clearly demonstrate that even when an endoscopic recurrent operation is performed in accordance with the guidelines, a poorer outcome must be expected because of the previous operation.

In the vast majority of cases, this is due to the fact that even when operating in another anatomic layer for the recurrent operation only rarely is no scarring encountered from the previous operation. As such, the conditions under which a recurrent operation is conducted are generally worse than those prevailing at the time of the primary operation, i.e., not just following previous endoscopic primary hernia operations. Therefore, a recurrent operation, i.e., also following previous open suture and mesh repair, calls for a particularly experienced surgeon. Accordingly, recurrent operations should always be performed by very experienced endoscopic hernia surgeons.

In summary, this present analysis of data from the Herniamed Registry is the first such analysis to demonstrate on the basis of a large prospective patient group the differences in outcome for up to 1 year between endoscopic repair of primary and recurrent inguinal hernia. Even when proceeding in compliance with the guidelines of the international specialist societies, more unfavorable outcomes must be expected for recurrent inguinal hernia. Hence, repair of recurrent hernias calls for particular expertise on the part of the endoscopic hernia surgeons.

References

Sevonius D, Gunnarsson U, Nordin P, Nilsson E, Sandblom G (2011) Recurrent groin hernia surgery. Br J Surg 98:1489–1494. doi:10.1002/bjs.7559

Burcharth J, Pommergaard HC, Bisgaard T, Rosenberg J (2014) Patient-related risk factors for recurrence after inguinal hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Surg Innov. doi:10.1177/1553350614552731

Karthikesalingam A, Markar SR, Holt PJE, Praseedom RK (2010) Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing laparoscopic with open mesh repair of recurrent inguinal hernia. Br J Surg 97:4–11. doi:10.1002/bjs.6902

Dedemadi G, Sgourakis G, Radtke A et al (2010) Laparoscopic versus open mesh repair for recurrent inguinal hernia: a meta-analysis of outcomes. Am J Surg 200:291–297. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.12.009

Yang J, Tong DN, Yao J, Chen W (2012) Laparoscopic or Lichtenstein repair for recurrent inguinal hernia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. ANZ J Surg. doi:10.1111/ans.12010

Pisanu A, Podda M, Saba A, Saba A, Porceddu G, Uccheddu A (2014) Meta-analysis and review of prospective randomized trials comparing laparoscopic and Lichtenstein techniques in recurrent inguinal hernia repair. Hernia. doi:10.1007/s10029-014-1281-1

Li J, Ji Z, Li Y (2014) Comparison of Laparoscopic versus open procedure in the treatment of recurrent inguinal hernia: a meta-analysis of results. Am J Surg 207:602–612

Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M et al (2009) European Hernia Society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia 13:343–403. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0529-7

Bittner R, Arregui ME, Bisgaard T et al (2011) Guidelines for laparoscopic (TAPP) and endoscopic (TEP) treatment of inguinal Hernia. Surg Endosc 25:2773–2843. doi:10.1007/s00464-011-1799-6

Poelman MM, Heuvel B, Deelder JD et al (2013) EAES Consensus Development Conference on endoscopic repair of groin hernias. Surg Endosc 27:3505–3519. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-3001-9

Chiofalo R, Holzinger F, Klaiber C (2001) Total endoscopic pre-peritoneal mesh implant in primary or recurrent inguinal hernias. Chirurg 72(12):1485–1491

Stechemesser B, Jacob DA, Schug-Pass C, Köckerling F (2012) Herniamed: an internet-based registry for outcome research in hernia surgery. Hernia 16(3):269–276. doi:10.1007/s10029-012-0908-3

Miserez M, Alexandre JH, Campanelli G et al (2007) The European hernia society groin hernia classification: simple and easy to remember. Hernia 11(2):113–611

Acknowledgments

Ferdinand Köckerling—Grants to fund the Herniamed Registry from Johnson & Johnson, Norderstedt, Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, pfm medical, Cologne, Dahlhausen, Cologne, B Braun, Tuttlingen, MenkeMed, Munich and Bard, Karlsruhe

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

D. Jacob, W. Wiegank, M. Hukauf, C. Schug-Pass, A. Kuthe, and R. Bittner have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose

Appendix: Herniamed Study Group

Appendix: Herniamed Study Group

Scientific Board

Köckerling, Ferdinand (Chairman) (Berlin); Berger, Dieter (Baden–Baden); Bittner, Reinhard (Rottenburg); Bruns, Christiane (Magdeburg); Dalicho, Stephan (Magdeburg); Fortelny, René (Wien); Jacob, Dietmar (Berlin); Koch, Andreas (Cottbus); Kraft, Barbara (Stuttgart); Kuthe, Andreas (Hannover); Lippert, Hans (Magdeburg): Lorenz, Ralph (Berlin); Mayer, Franz (Salzburg); Moesta, Kurt Thomas (Hannover); Niebuhr, Henning (Hamburg); Peiper, Christian (Hamm); Pross, Matthias (Berlin); Reinpold, Wolfgang (Hamburg); Simon, Thomas (Sinsheim); Stechemesser, Bernd (Köln); Unger, Solveig (Chemnitz).

Participants

Ahmetov, Azat (Saint-Petersburg); Alapatt, Terence Francis (Frankfurt/Main); Anders, Stefan (Berlin); Anderson, Jürina (Würzburg); Arndt, Anatoli (Elmshorn); Asperger, Walter (Halle); Avram, Iulian (Saarbrücken); Barkus; Jörg (Velbert); Becker, Matthias (Freital); Behrend, Matthias (Deggendorf); Beuleke, Andrea (Burgwedel); Berger, Dieter (Baden–Baden); Bittner, Reinhard (Rottenburg); Blaha, Pavel (Zwiesel); Blumberg, Claus (Lübeck); Böckmann, Ulrich (Papenburg); Böhle, Arnd Steffen (Bremen); Böttger, Thomas Carsten (Fürth); Borchert, Erika (Grevenbroich); Born, Henry (Leipzig); Brabender, Jan (Köln); Brauckmann, Markus (Rüdesheim am Rhein); Breitenbuch von, Philipp (Radebeul); Brüggemann, Armin (Kassel); Brütting, Alfred (Erlangen); Budzier, Eckhard (Meldorf); Burghardt, Jens (Rüdersdorf); Carus, Thomas (Bremen); Cejnar, Stephan-Alexander (München); Chirikov, Ruslan (Dorsten); Comman, Andreas (Bogen); Crescenti, Fabio (Verden/Aller); Dapunt, Emanuela (Bruneck); Decker, Georg (Berlin); Demmel, Michael (Arnsberg); Descloux, Alexandre (Baden); Deusch, Klaus-Peter (Wiesbaden); Dick, Marcus (Neumünster); Dieterich, Klaus (Ditzingen); Dietz, Harald (Landshut); Dittmann, Michael (Northeim); Dornbusch, Jan (Herzberg/Elster); Drummer, Bernhard (Forchheim); Eckermann, Oliver (Luckenwalde); Eckhoff, Jörn/Hamburg); Elger, Karlheinz (Germersheim); Engelhardt, Thomas (Erfurt); Erichsen, Axel (Friedrichshafen); Eucker, Dietmar (Bruderholz); Fackeldey, Volker (Kitzingen); Farke, Stefan (Delmenhorst); Faust, Hendrik (Emden); Federmann, Georg (Seehausen); Feichter, Albert (Wien); Fiedler, Michael (Eisenberg); Fischer, Ines (Wiener Neustadt); Fortelny, René H. (Wien); Franczak, Andreas (Wien); Franke, Claus (Düsseldorf); Frankenberg von, Moritz (Salem); Frehner, Wolfgang (Ottobeuren); Friedhoff, Klaus (Andernach); Friedrich, Jürgen (Essen); Frings, Wolfram (Bonn); Fritsche, Ralf (Darmstadt); Frommhold, Klaus (Coesfeld); Frunder, Albrecht (Tübingen); Fuhrer, Günther (Reutlingen); Gassler, Harald (Villach); Gawad, Karim A. Frankfurt/Main); Gerdes, Martin (Ostercappeln); Gilg, Kai-Uwe (Hartmannsdorf); Glaubitz, Martin (Neumünster); Glutig, Holger (Meißen); Gmeiner, Dietmar (Bad Dürrnberg); Göring, Herbert (München); Grebe, Werner (Rheda-Wiedenbrück); Grothe, Dirk (Melle); Gürtler, Thomas (Zürich); Hache, Helmer (Löbau); Hämmerle, Alexander (Bad Pyrmont); Haffner, Eugen (Hamm); Hain, Hans-Jürgen (Groß-Umstadt); Hammans, Sebastian (Lingen); Hampe, Carsten (Garbsen); Harrer, Petra (Starnberg); Heinzmann, Bernd (Magdeburg); Heise, Joachim Wilfried (Stolberg); Heitland, Tim (München); Helbling, Christian (Rapperswil); Hempen, Hans-Günther (Cloppenburg); Henneking, Klaus-Wilhelm (Bayreuth); Hennes, Norbert (Duisburg); Hermes, Wolfgang (Weyhe); Herrgesell, Holger (Berlin); Herzing, Holger Höchstadt); Hessler, Christian (Bingen); Hildebrand, Christiaan (Langenfeld); Höferlin, Andreas (Mainz); Hoffmann, Henry (Basel); Hoffmann, Michael (Kassel); Hofmann, Eva M. (Frankfurt/Main); Hopfer, Frank (Eggenfelden); Hornung, Frederic (Wolfratshausen); Hügel, Omar (Hannover); Hüttemann, Martin (Oberhausen); Huhn, Ulla (Berlin); Hunkeler, Rolf (Zürich); Imdahl, Andreas (Heidenheim); Jacob, Dietmar (Berlin); Jenert, Burghard (Lichtenstein); Jugenheimer, Michael (Herrenberg); Junger, Marc (München); Käs, Stephan (Weiden); Kahraman, Orhan (Hamburg); Kaiser, Christian (Westerstede); Kaiser, Stefan (Kleinmachnow); Kapischke, Matthias (Hamburg); Karch, Matthias (Eichstätt); Keck, Heinrich (Wolfenbüttel); Keller, Hans W. (Bonn); Kienzle, Ulrich (Karlsruhe); Kipfmüller, Brigitte (Köthen); Kirsch, Ulrike (Oranienburg); Klammer, Frank (Ahlen); Klatt, Richard (Hagen); Kleemann, Nils (Perleberg); Klein, Karl-Hermann (Burbach); Kleist, Sven (Berlin); Klobusicky, Pavol (Bad Kissingen); Kneifel, Thomas (Datteln); Knoop, Michael (Frankfurt/Oder); Knotter, Bianca (Mannheim); Koch, Andreas (Cottbus); Köckerling, Ferdinand (Berlin); Köhler, Gernot (Linz); König, Oliver (Buchholz); Kornblum, Hans (Tübingen); Krämer, Dirk (Bad Zwischenahn); Kraft, Barbara (Stuttgart); Kreissl, Peter (Ebersberg); Krones, Carsten Johannes (Aachen); Kruse, Christinan (Aschaffenburg); Kube, Rainer (Cottbus); Kühlberg, Thomas (Berlin); Kuhn, Roger (Gifhorn); Kusch, Eduard (Gütersloh); Kuthe, Andreas (Hannover); Ladberg, Ralf (Bremen); Ladra, Jürgen (Düren); Lahr-Eigen, Rolf (Potsdam); Lainka, Martin (Wattenscheid); Lammers, Bernhard J. (Neuss); Lancee, Steffen (Alsfeld); Lange, Claas (Berlin); Laps, Rainer (Ehringshausen); Larusson, Hannes Jon (Pinneberg); Lauschke, Holger (Duisburg); Leher, Markus (Schärding); Leidl, Stefan (Waidhofen/Ybbs); Lenz, Stefan (Berlin); Lesch, Alexander (Kamp-Lintfort); Liedke, Marc Olaf (Heide); Lienert, Mark (Duisburg); Limberger, Andreas (Schrobenhausen); Limmer, Stefan (Würzburg); Locher, Martin (Kiel); Loghmanieh, Siawasch (Viersen); Lorenz, Ralph (Berlin); Mallmann, Bernhard (Krefeld); Manger, Regina (Schwabmünchen); Maurer, Stephan (Münster); Mayer, Franz (Salzburg); Mellert, Joachim (Höxter); Menzel, Ingo (Weimar); Meurer, Kirsten (Bochum); Meyer, Moritz (Ahaus); Mirow, Lutz (Kirchberg); Mittenzwey, Hans-Joachim (Berlin); Mörder-Köttgen, Anja (Freiburg); Moesta, Kurt Thomas (Hannover); Moldenhauer, Ingolf (Braunschweig); Morkramer, Rolf (Xanten); Mosa, Tawfik (Merseburg); Müller, Hannes (Schlanders); Münzberg, Gregor (Berlin); Mussack, Thomas (St. Gallen); Neumann, Jürgen (Haan); Neumeuer, Kai (Paderborn); Niebuhr, Henning (Hamburg); Nölling, Anke (Burbach); Nostitz, Friedrich Zoltán (Mühlhausen); Obermaier, Straubing); Öz-Schmidt, Meryem (Hanau); Oldorf, Peter (Usingen); Olivieri, Manuel (Pforzheim); Pawelzik, Marek (Hamburg); Peiper, Christian (Hamm); Peitgen, Klaus (Bottrop); Pertl, Alexander (Spittal/Drau); Philipp, Mark (Rostock); Pickart, Lutz (Bad Langensalza); Pizzera, Christian (Graz); Pöllath, Martin (Sulzbach-Rosenberg); Possin, Ulrich (Laatzen); Prenzel, Klaus (Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler); Pröve, Florian (Goslar); Pronnet, Thomas (Fürstenfeldbruck); Pross, Matthias (Berlin); Puff, Johannes (Dinkelsbühl); Rabl, Anton (Passau); Rapp, Martin (Neunkirchen); Reck, Thomas (Püttlingen); Reinpold, Wolfgang (Hamburg); Reuter, Christoph (Quakenbrück); Richter, Jörg (Winnenden); Riemann, Kerstin (Alzenau-Wasserlos); Rodehorst, Anette (Otterndorf); Roehr, Thomas (Rödental); Roncossek, Bremerhaven); Roth Hartmut (Nürnberg); Sardoschau, Nihad (Saarbrücken); Sauer, Gottfried (Rüsselsheim); Sauer, Jörg (Arnsberg); Seekamp, Axel (Freiburg); Seelig, Matthias (Bad Soden); Seidel, Hanka (Eschweiler); Seiler, Christoph Michael (Warendorf); Seltmann, Cornelia (Hachenburg); Senkal, Metin (Witten); Shamiyeh, Andreas (Linz); Shang, Edward (München); Siemssen, Björn (Berlin); Sievers, Dörte (Hamburg); Silbernik, Daniel (Bonn); Simon, Thomas (Sinsheim); Sinn, Daniel (Olpe); Sinning, Frank (Nürnberg); Smaxwil, Constatin Aurel (Stuttgart); Schabel, Volker (Kirchheim/Teck); Schadd, Peter (Euskirchen); Schassen von, Christian (Hamburg); Schattenhofer, Thomas (Vilshofen); Scheidbach, Hubert (Neustadt/Saale); Schelp, Lothar (Wuppertal); Scherf, Alexander (Pforzheim); Scheyer, Mathias (Bludenz); Schimmelpenning, Hendrik (Neustadt in Holstein); Schinkel, Svenja (Kempten); Schmid, Michael (Gera); Schmid, Thomas (Innsbruck); Schmidt, Rainer (Paderborn); Schmidt, Sven-Christian (Berlin); Schmidt, Ulf (Mechernich); Schmitz, Heiner (Jena); Schmitz, Ronald (Altenburg); Schöche, Jan (Borna); Schoenen, Detlef (Schwandorf); Schrittwieser, Rudolf/Bruck an der Mur); Schroll, Andreas (München); Schultz, Christian (Bremen-Lesum); Schultz, Harald (Landstuhl); Schulze, Frank P. Mülheim an der Ruhr); Schumacher, Franz-Josef (Oberhausen); Schwab, Robert (Koblenz); Schwandner, Thilo (Lich); Schwarz, Jochen Günter (Rottenburg); Schymatzek, Ulrich (Radevormwald); Spangenberger, Wolfgang (Bergisch-Gladbach); Sperling, Peter (Montabaur); Staade, Katja (Düsseldorf); Staib, Ludger (Esslingen); Stamm, Ingrid (Heppenheim); Stark, Wolfgang (Roth); Stechemesser, Bernd (Köln); Steinhilper, Uz (München); Stengl, Wolfgang (Nürnberg); Stern, Oliver (Hamburg); Stöltzing, Oliver (Meißen); Stolte, Thomas (Mannheim); Stopinski, Jürgen (Schwalmstadt); Stubbe, Hendrik (Güstrow/); Stülzebach, Carsten (Friedrichroda); Tepel, Jürgen (Osnabrück); Terzić, Alexander (Wildeshausen); Teske, Ulrich (Essen); Thews, Andreas (Schönebeck); Tichomirow, Alexej (Brühl); Tillenburg, Wolfgang (Marktheidenfeld); Timmermann, Wolfgang (Hagen); Tomov, Tsvetomir (Koblenz; Train, Stefan H. (Gronau); Trauzettel, Uwe (Plettenberg); Triechelt, Uwe (Langenhagen); Ulcar, Heimo (Schwarzach im Pongau); Unger, Solveig (Chemnitz); Verweel, Rainer (Hürth); Vogel, Ulrike (Berlin); Voigt, Rigo (Altenburg); Voit, Gerhard (Fürth); Volkers, Hans-Uwe (Norden); Vossough, Alexander (Neuss); Wallasch, Andreas (Menden); Wallner, Axel (Lüdinghausen); Warscher, Manfred (Lienz); Warwas, Markus (Bonn); Weber, Jörg (Köln); Weiß, Johannes (Schwetzingen); Weißenbach, Peter (Neunkirchen); Werner, Uwe (Lübbecke-Rahden); Wessel, Ina (Duisburg); Weyhe, Dirk (Oldenburg); Wieber, Isabell (Köln); Wiesmann, Aloys (Rheine); Wiesner, Ingo (Halle); Withöft, Detlef (Neutraubling); Woehe, Fritz (Sanderhausen); Wolf, Claudio (Neuwied); Yildirim, Selcuk (Berlin); Zarras, Konstantinos (Düsseldorf); Zeller, Johannes (Waldshut-Tiengen); Zhorzel, Sven (Agatharied); Zuz, Gerhard (Leipzig).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Köckerling, F., Jacob, D., Wiegank, W. et al. Endoscopic repair of primary versus recurrent male unilateral inguinal hernias: Are there differences in the outcome?. Surg Endosc 30, 1146–1155 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4318-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4318-3