Abstract

Part-time jobs are common among partnered women in many countries. There are two opposing views on the efficiency implications of so many women working part-time. The negative view is that part-time jobs imply wastage of resources and underutilization of investments in human capital since many part-time working women are highly educated. The positive view is that, without the existence of part-time jobs, female labor force participation would be substantially lower since women confronted with the choice between a full-time job and zero working hours would opt for the latter. In the Netherlands, the majority of partnered working women have a part-time job. Our paper investigates, from a supply-side perspective, if the current situation of abundant part-time work in the Netherlands is likely to be a transitional phase that will culminate in many women working full-time. Our main results indicate that partnered women in part-time work have high levels of job satisfaction, a low desire to change their working hours, and live in partnerships in which household production is highly gendered. Taken together, our results suggest that part-time jobs are what most Dutch women want.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Across OECD countries, there are big differences in the share of part-time work in employment among prime-age female workers. In 2007, the female part-time share of women workers aged between 25 and 54 years ranged from a high of 60% in Switzerland and 54% in the Netherlands to a low of 9% in Greece. An interesting question is whether or not the current situation of plentiful part-time work in some countries is likely to be an intermediate stage en route to a greater proportion of women in full-time jobs.

There are two opposing views on the efficiency implications of so many women working part-time. The negative view is that part-time jobs imply wastage of resources and underutilization of investments in human capital, since many part-time working women are highly educated.Footnote 1 The positive view is that, without the existence of part-time jobs, female labor force participation would be substantially lower since women confronted with the choice between a full-time job and zero working hours would opt for the latter.

Against this background, the purpose of our paper is to investigate, from a supply-side perspective, if the current situation of abundant part-time work in the Netherlands is likely to be a transitional phase culminating in many women working in full-time jobs. Our econometric analysis, using panel data on life and job satisfaction of a sample of partnered women and men, assumes that dissatisfaction with a particular work status is likely to lead to changes in working hours in the future. In addition, we utilize time-use data to consider the distribution of market work and housework within the household. We also discuss the work specialization hypothesis in this context. If the Netherlands is characterized by little gender-stereotyping about working roles, we would expect to see that, on average in our sample of partnered households, the male share of domestic work is increasing in the female partner’s share of market work. If this is not the case, it suggests that there is a gendered division of household and market labor within the family unit.

Our approach differs from that in earlier studies that investigate whether or not part-time work represents a stepping stone between nonwork and full-time employment. For example, Blank (1989) used US data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics to explore transitions between the states of full-time, part-time, or nonwork over the period 1976–1984 for a sample of women aged 18–60 in 1976 who were either household heads or spouses. Blank found that three out of four women over the 9 years remained predominantly in that state and that very few women use part-time work as a stepping stone from nonwork to full-time work. In Sweden, Sundström (1991) shows that part-time work has not marginalized women but instead has increased the continuity of their labor force attachment, strengthened their position in the labor market, and reduced their economic dependency. Continuous part-time employment has replaced work interruptions during child rearing years. Moreover, the growth in part-time work has not been followed by increasing difficulties for women working part-time to shift to full-time work (Sundström 1991). Thus, the initial increase in part-time work in Sweden might be viewed as a transitional phase leading to many Swedish women working full-time.Footnote 2

In the Netherlands, currently almost half of the part-time working women are over 40 and no longer have young children. However, about 40% of women with part-time jobs are mothers of young children who work part-time because they either prefer this or have no choice but to provide childcare themselves. A little over 10% of women with part-time jobs are mothers with older children. So, the majority of part-time working women are those with family responsibilities. Therefore, we focus on partnered individuals in our empirical analysis. Now that most women in the Netherlands work part-time, an important question is whether or not part-time jobs are indeed what Dutch women want.

Our paper is set out as follows. In the next section, we provide information on part-time work in the Netherlands, and we briefly review previous studies looking at the relationship between part-time work and partnered life and job satisfaction. Section 3 presents a fixed effects empirical analysis of the relationship between part-time work and life satisfaction. Section 4 investigates job satisfaction and working hour preferences, while Section 5 analyzes time use from a household perspective. Section 6 concludes.

As will be seen, our main results indicate that partnered women in part-time work in the Netherlands have high levels of job satisfaction, a low desire to change their working hours, and they live in partnerships in which household production is highly gendered. Taken together, these results suggest that part-time work in the Netherlands is here to stay, at least in the near future.

2 Background

2.1 Part-time work in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the number of part-time jobs has expanded rapidly over the past decade due to a gradual change in policy causing barriers for part-time employment to be removed. Laws were implemented that made part-time work more attractive. In 1993, the statutory exemption of jobs of less than one-third of the normal working week from application of the legal minimum wage and related social security entitlements were abolished. Currently, most taxes are neutral and social security benefits are usually pro rata. In 1995, unions and employers signed the first proper collective agreement for temporary workers. In 2000, a right to part-time work law was introduced. Because the government introduced legislation ensuring that the rights of part-time workers are properly protected, part-time work is not limited to marginal jobs but is a feature of mainstream employment (Portegijs and Keuzenkamp 2008). According to Portegijs et al. (2008), the part-time job in the Netherlands was born in the 1950s when, in response to shortages of young female staff, firms began to offer part-time jobs to married women. According to Portegijs et al. (2008), in countries like Spain, the UK, Germany, and France, governments aim to make part-time work more attractive for employers, while the Netherlands and Sweden are the only countries where policy aims at making part-time work more attractive for workers.Footnote 3 Many women in “small” part-time jobs prefer to work longer while many women in “large” part-time jobs prefer to work shorter hours.Footnote 4 A part-time job between 20 and 27 h a week would be women’s preferred choice (Portegijs et al. 2008).

Apart from supply-side factors, changes in labor demand may have been important too. Euwals and Hogerbrugge (2006) distinguish between dynamic flexibility—adjustment to the business cycle—and organizational flexibility—adjustment to nonstandard working hours. They conclude that dynamic flexibility cannot explain the strong growth of part-time employment, but the need for organizational flexibility, related to the shift from manufacturing to services, might have contributed. Bosch et al. (2010) analyze the growth of part-time work distinguishing between age, calender time, and cohort effects. They find that the incidence of part-time work has increased over successive generations at the expense of full-time and small part-time jobs. As a result, the average working hours of working women remained stable over successive cohorts. Finally, Bosch and Van der Klaauw (2012), analyzing the effects of a 2001 tax reform which made work much more financially attractive for women with a high-income partner, find that women actually reduced their working hours slightly in response to receiving a higher after-tax hourly wage.

Previous studies are important in charting patterns of work mobility, which can be used as a basis for predicting future behavior using comparative static techniques. However, we choose in the present paper to adopt the alternative approach described above, in which we use couple’s (dis)satisfaction with working hours and the division of responsibilities within the household to make inferences about expected future working behavior of partnered women. As noted in the introduction to this paper, the proportion of the Dutch female workforce engaged in part-time work is the highest of all the European Union countries and one of the highest of all OECD countries. Hence, it is interesting to see if we can expect this to be a transitory phenomenon or if instead it is likely to shift towards the European average. Since there is no single Dutch data source that allows us to investigate all these issues, we use a variety of micro datasets to be described in detail from Section 3 onwards.

2.2 Previous studies of partnered work and satisfaction

Self-reported measures of life and job satisfaction are widely used measures of well-being and have been shown to be closely related to a range of other potentially more objective measures of happiness (Frey and Stutzer 2002). There is a large and growing economics literature on the determinants of various components of satisfaction and happiness (see for example: Clark 1997; Van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell 2004; Herbst 2012; Schwarze and Winkelmann 2011; Pérez-Asenjo 2011). However, few studies have explicitly investigated how part-time work status affects family life satisfaction, and we briefly summarize these below.

Women may prefer part-time work because it satisfies their hour preferences given their constraints. Although part-time work could increase hours satisfaction, it might not necessarily increase job satisfaction. For example, Connolly and Gregory (2008) and Manning and Petrongolo (2008) show that part-timers in Britain are doing more menial work at lower pay than if they were full-time. So if part-time jobs are bad jobs, overall job satisfaction might be lower. What about the effect of part-time work on overall life satisfaction? This is unclear a priori. Part-time work is likely to provide flexible working and caring hours while maintaining an individual’s social connection. On the other hand, working part-time might be intrinsically unsatisfying, affording little in the way of future advancement and characterized by low prestige. Consequently, part-time work might reduce life satisfaction through this avenue. Ultimately, it is an empirical issue as to which effect dominates.

In our previous work—Booth and Van Ours (2008; Booth and Van Ours (2009)—we studied preferences concerning part-time work in the UK and Australia in particular. In Booth and Van Ours (2009), we used Australian panel data and focused on a sample of partnered men and women. Our results indicate that, conditional on observed characteristics, partnered women’s life satisfaction is reduced by working full-time, especially so if their weekly hours are greater than 40. However, female life satisfaction is increasing if their partners are working full-time, and they are particularly happy if their partners are working 35–50 h per week. In contrast, male partners’ life satisfaction is unaffected by their partners’ market hours but is significantly increased if they themselves are working full-time and especially so if they are working 35–50 h. Thus, it seems that full-time work for men in the region of 35–50 h is the major contributor to both partners’ life happiness but that female part-time work has an asymmetric effect. Men do not mind what their partners do in terms of working hours, but women are happiest with part-time work.

In Booth and Van Ours (2008), we investigated the same relationships using British panel data for partnered men and women. Life satisfaction of British men is influenced only by whether or not they have a job. Life satisfaction of British women without children is unaffected by their hours of work, while women with children are happier if they have a job. Apparently, British women are happy about their part-time job even though this does not increase their overall life satisfaction. It is interesting that we also found that work increased partnered male life satisfaction. In this sense, the finding for female life satisfaction parallels that of men.

3 Life satisfaction and part-time work

In order to analyze the relationship between part-time work and life satisfaction among Dutch partnered women, we use information collected by CentER data through an internet-based panel.Footnote 5 Within each household, all individuals aged 16 or over are interviewed about work, income, health, and a number of other demographic attributes. We have data on fourteen annual waves (from 1993 to 2006). Our sample is restricted to married or cohabiting couples, in which the female partner is aged between 23 and 50 years in 1993. In addition, couples in which the male partner is older than 60 in 2006 are dropped because such males are much less likely to participate in the labor market.

Important questions in the survey concern health and happiness. The question about health is specified as follows: “In general, would you say your health is: 1 poor, 2 not so good, 3 fair, 4 good and 5 excellent”. The question about happiness in the CentER data is specified as follows: “All in all, to what extent do you consider yourself a happy person?” with the possible answers of 1 (very unhappy), 2 (unhappy), 3 (neither happy nor unhappy), 4 (happy), or 5 (very happy). This type of life satisfaction question is a widely used measure of well-being, and Frey and Stutzer (2002), inter alia, have shown it to be closely related to a number of other potentially more objective measures of happiness.

The upper part of Fig. 1 presents a histogram of normal weekly working hours in the main job for men and women, respectively. Working hours are divided into four categories: small part-time jobs (1–20 h per week), part-time jobs (21–32 h per week), full-time jobs (33–40 h per week), and large full-time jobs (more than 40 h per week). About 35% of the women do not work and very few women work more than 40 h a week.

Table 1 presents the distribution of life satisfaction of partnered men and women. More women are “very happy” than men, but more men report being “happy” than women. The average value for life satisfaction is about the same.

In Table 2, the averages of life satisfaction values for workers stratified by hours of work are presented. The lower part of Fig. 1 gives a visual representation of the relationship between life satisfaction and weekly working hours. Women have, on average, a higher value for life satisfaction than men for every category. Men are less satisfied if they work less. For men, there is a clear positive relationship; while for women, life satisfaction seems to be almost independent of hours of work.

In order to study the relationship between hours of work and life satisfaction, we have to take the effects of observed and unobserved personal characteristics into account. Otherwise, the relationship between the two variables of interest could be spurious. In order to account for the effect of unobserved characteristics, the use of panel data techniques is important. Although happiness research in the economics literature has been underway for over a decade, it is only relatively recently that panel data techniques have been employed to control for unobserved individual heterogeneity. Cross-sectional equations facilitate the establishment of correlation rather than causation. This is because unobserved personal characteristics—such as an extrovert personality type—can be correlated both with the propensity to report happiness and with the explanatory variables of interest. Thus, the coefficients for the latter are possibly biased in cross-sectional work. The use of panel data can overcome this problem to the extent that personality traits are fixed over time. In most of the existing satisfaction literature utilizing panel data, fixed effects binomial logit models are used with an arbitrary common fixed cut point to reduce the categorical satisfaction scale to a (0,1) scale, permitting fixed effects estimation of a binomial logit model using Chamberlain’s method. Unfortunately, this method comes at a large cost, since only those individuals moving across the cutoff point can be used in the estimation. As in our previous studies (Booth and Van Ours 2008, 2009), rather than adopting this procedure, we use simple reformulation that removes both individual-specific effects and thresholds from the likelihood specification. Thus, we can use Chamberlain’s method, but all changes in satisfaction are exploited and not just those across some arbitrary cut point.

In our empirical analysis, we use an ordered logit model in which in addition to time-varying explanatory variables x, we introduce individual fixed effects α i and individual-specific thresholds μ ij :

The x variables are own health status (dummy variable for good or excellent health), working hours (four dummy variables for 1–20, 21–32, 33–40, and 40+ h per week), partners’ health, partners’ working hours, and family income. Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004) show that, by choosing for every individual a specific barrier k i , the fixed effects ordered logit specification can be reformulated as a fixed effects binomial logit. So instead of a common cutoff point, individual-specific cutoff points are chosen. This reformulation removes the individual-specific effects α i as well as the individual-specific thresholds μ ij from the likelihood specification.Footnote 6

This setup allows for the effects of unobserved time-invariant fixed effects but does not deal with the potential influence of unobserved time-varying effects. An individual-specific shock may affect both the choice of hours of work and life satisfaction. To the extent that this is the case, our parameter estimates of the effect of hours of work on life satisfaction may be biased. We are not aware of any studies in happiness research that deal with the issue of unobserved time-varying effects. For the moment, we ignore the possible influence of time-varying individual effects. However, later in this section, in order to study whether these effects may bias our estimates, we perform a sensitivity analysis in which we include additional variables representing time-varying shocks to the individual.

Table 3 presents the parameter estimates of fixed effects ordered logit estimates. As shown, own health has a positive and significant effect on life satisfaction, whereas the health of the partner is irrelevant.Footnote 7 The estimates in the first column show that men have a higher life satisfaction if they work more than 20 h per week. Men also prefer their spouses to work part-time. For women (see estimates reported in the third column), only their own health matters, and their life satisfaction is independent of whether or not they work, or how many hours they work. Table 3 also shows that introducing family income as explanatory variable does not alter the results. Family income has no significant effect on life satisfaction, and the other parameter estimates are little affected. However, the inclusion of household income does reduce the statistical significance of the hours of work variables, which indicates that some of the effect of hours of work on life satisfaction works through the effect on family income.Footnote 8

In summary, men are happiest if they work in a large part-time or a full-time job. They are also happier if their partner works in a part-time job, although once household income is accounted for, their life satisfaction is unaffected by their partners’ hours. While women are indifferent with respect to their own working hours and the working hours of their partner, once household income is accounted for, their life satisfaction is reduced by working 40 or more hours (though this is not statistically significant).

Since partnered female life satisfaction is largely unaffected by their own hours of work, it seems that there is unlikely to be a strong desire to change working status from part-time to full-time in order to improve the quality of their lives. This is again suggestive of part-time work not being a transitory phase to full-time work.

As indicated above, our analysis allows for the effects of unobserved time-invariant fixed effects, but it does not deal with unobserved time-varying effects. In order to investigate the potential relevance of these effects, we experimented with additional explanatory variables that represent time-varying shocks to the individual and that might affect both the working hour choice and life satisfaction. The first variable we included is the number of children. An increase in the number of children over time indicates a birth. We find that the number of children itself has no significant effect on life satisfaction.Footnote 9 Furthermore, the effects of working hours on life satisfaction remain virtually unaffected. Second, we included dummies for provinces in the Netherlands to allow for the effect of a move from one province to another province. Again, our main parameter estimates remain unaffected. From this, we conclude that time-varying unobserved effects are not likely to bias our main parameter estimates.

4 Job satisfaction and preferred working hours

In order to study job satisfaction and preferred working hours, we use data from the OSA labor supply panel (from the former Institute for Labor Studies), a biennial panel survey of a representative sample of Dutch households.Footnote 10 The panel covers a broad range of work and life course related items. In order to make the sample comparable to the CentER data panel, we restrict the OSA sample to female age between 22 and 49 in 1992, while couples in which the male partner is older than 60 in 2006 are again dropped.

The data contain information about job satisfaction and preferred working hours. The question about job satisfaction is specified as follows: “How satisfied are you all in all with your work?” with the possible answers of 4 (very satisfied), 3 (satisfied), 2 (dissatisfied), and 1 (very dissatisfied). As shown in Table 1, few men and women are in the lowest categories, while more than half of workers is in category 3. The bottom panel of Table 2 shows the relationship between hours of work and job satisfaction. For women, there is a slight increase in job satisfaction with working hours. For men, job satisfaction is lowest if the job is 21–32 h per week. Men who work more than 40 h per week on average have the highest job satisfaction.

Table 4 shows the parameter estimates of the fixed effects logit model for job satisfaction.Footnote 11 Male workers have the lowest job satisfaction if they work more than 21–32 h per week. They have the highest job satisfaction if they work fewer than 21 h per week, but none of the hours category parameter of the job satisfaction is different from zero at conventional levels of significance. Female workers have the highest job satisfaction if they work 33–40 h per week. Introducing wage satisfaction as explanatory variable for job satisfaction shows that this has a positive effect, while the parameter estimates of the hour categories are hardly affected.

Table 5 presents a cross tabulation of preferred working hours separately for men and women. The last column in the bottom panel of the table shows that about 9% of all women want to work more hours and 12% want to work less. The top panel shows that, for men, 12% wants to work more and 21% wants to work less. In order to analyze preferred working hours, we use a fixed effects logit model in which the dependent variables are indicators for whether workers want to work fewer hours or want to work longer hours. Table 6 shows the parameter estimates. Clearly, preferences for working more hours are decreasing as working hours increase, and similarly, preferences for working less are increasing with hours worked.

Figure 2 presents working hour preferences, i.e., sample percentages of employees wanting to work more and less by actual hours of work. Partnered women are shown in the top panel and partnered men in the bottom. Clearly, most partnered individuals working long hours would prefer to work less, while most partnered individuals working short hours would prefer to work more. It is interesting to see the “equilibrium” hours of work, i.e., the number of hours at which there are as many individuals wanting to work fewer hours as there are individuals wanting to work longer hours.Footnote 12 In order to determine this “crossing point,” we estimated a linear probability model of the probability of wanting to work more and the probability of wanting to work less, with the number of weekly working hours and calendar time as the independent variables. This is given as follows:

where h denotes the actual weekly working hours and \(\Pr (h_{i}^{+})\) (\( \Pr (h_{i}^{-})\)) denotes the probability of wanting to work more (fewer) hours. From Eq. 2, the “equilibrium” of preferred working hours \(h_{t}^{\ast }\) can be calculated as the following:

Because we are interested in the evolution of preferred working hours over time, we estimate Eq. 2 over a separate sample covering the period 1985–2006 by using information about men and women aged 25–54 years and working 1–45 h per week at the time of the survey. We estimate Eq. 2 using a linear probability model. Table 7 shows the parameter estimates. As before, we find that, with an increase of actual hours of work, both men and women are less likely to prefer working more and more likely to prefer working less. Over time, for both men and women, preferences for working more and for working less go down. For men, the drop in preferences for working more is larger than the drop in preferences for working less. This indicates that, over time, the “equilibrium” hours of work goes down for men. For women, the calendar time parameter estimates for working more and for working less are about the same size. This indicates that the “equilibrium” hours of work for women has not changed over time. Based on the parameter estimates presented in Table 7, we calculate that, in 2005, the “equilibrium” hours of work for women would have been 21.7 h per week, while for men, it would have been 32.5 h, reducing from 36.9 h in 1985.

All in all, we conclude that our main results indicate that partnered women in part-time work in the Netherlands have high levels of job satisfaction and a low desire to change their working hours. Again, this is evidence that part-time work is not a transitory phase en route to full-time work.

5 Time use—a household perspective

Theories of household behavior, such as that put forward by Becker (1965), predict that partnered households will be characterized by specialization of labor, whereby in the extreme case, one partner engages fully in home work and the other in market sector work.Footnote 13 Part-time jobs provide a means of combining domestic and market production while maintaining workforce skills or experience capital for the future. Part-time work thereby facilitates incomplete specialization by either gender. The specialization hypothesis predicts gender differences in working hours because partners within a household specialize (completely or incompletely) in either market work or house work. However, the prediction is symmetric: if one partner specializes in market work, the other will specialize in home production, and in principle there is no a priori reason why the partner specializing in market work should be female or male.

In contrast, the gender identity hypothesis of Akerlof and Kranton (2000) is based on the idea that gender matters. Here, the distribution of household work and market work is determined by gender-specific “utility”. According to this approach, since individuals operate within society’s constraints, their happiness and the gender division of labor could be powerfully affected by social custom and conditioning. It is possible that—controlling for income—part-time jobs could make partnered women happier than either full-time work or no work, because such jobs allow them to gain esteem through working, while obtaining social and self-approbation from being with and caring for their families and their homes.

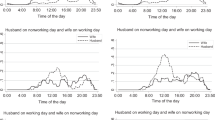

In this section, we use information from the Dutch Time Use Surveys for the years 2000 and 2005.Footnote 14 Figure 3 shows the relationship between hours of housework as a function of hours of market work of the woman, for couples with a full-time working male partner.Footnote 15 The household activities incorporated within the “housework” measure include the following: preparation of lunch/dinner, making table ready for dinner, doing the dishes, vacuum cleaning, cleaning windows/doors, doing the floors, cleaning toilet/bathroom, waxing floor and cleaning furniture, cleaning the beds, washing clothes, drying clothes, ironing clothes, fixing clothes, and watering plants (inside the house).

The figure shows that, as female hours of market work increase, male hours of housework remain almost constant. For women, hours of housework decline as hours of market work increase, but they do so at less than one for one. Indeed, initially extra market hours do not lead to a decrease of housework hours, but beyond 12 weekly hours of market work, there is approximately half an hour reduction of housework for every additional hour of market work. So, the net increase of working hours for every additional market hour is half an hour. Hence, the marginal hour burden is about 0.5 for women, providing support for the gender identity hypothesis.

In summary, we conclude from this analysis of time-use data that there is a clear gender bias in the division of labor within the household. In households where the male works full-time, an increase in market work of the female leads to a less than proportional decrease in her housework, while her partner’s housework stays much the same. Thus, the degree of specialization is partial and nonsymmetric. This finding suggests gender-stereotyping in market and house work roles, ceteris paribus. That Dutch men and women appear on average satisfied with this state of affairs, at least according to the findings of the previous two sections looking at market work and its relationship to life and job satisfaction, suggests that part-time female work patterns are here to stay, at least in the short term.

6 Conclusions

In the Netherlands, the majority of working women have a part-time job. There are two opposing views on the efficiency implications of so many women working part-time. The negative view is that part-time jobs imply wastage of resources and underutilization of investments in human capital since many part-time working women are highly educated. The positive view is that, without the existence of part-time jobs, female labor force participation would be substantially lower since women confronted with the choice between a full-time job and zero working hours would opt for the latter. This study investigated whether, from a supply-side perspective, the current situation of abundant part-time work in the Netherlands is a transitional phase that will end in many women working in full-time jobs. In our analysis, we focused on partnered individuals and the relationship between hours of work and life satisfaction. Furthermore, we investigated preferences for working hours and considered the distribution of market work and housework within the household.

With regard to life satisfaction, we find that men are happiest if they work in a large part-time or a full-time job. They are also happier if their partner works in a part-time job, although once household income is accounted for, their life satisfaction is unaffected by their partners’ hours. While women are indifferent with respect to their working hours and the working hours of their partner, once household income is accounted for, their life satisfaction is reduced if they work 40 or more hours. Both men and women who work in small jobs prefer to work more, while those working in jobs with long working hours prefer to work less. Using data on preferred working hours, we calculated the number of hours at which there is an equilibrium in the sense that the number of individuals wanting to work more is as large as the number of individuals wanting to work less. For women, the equilibrium number of weekly working hours is about 21, while for men, it is about 32. Finally, when investigating the division of labor within the household, we conclude that there is a clear gender bias. In households where the male works full-time in the market sector, an increase in market work by the female is associated with a less than proportional decrease in her housework while the partner’s housework stays much the same. Thus, the degree of specialization is partial and nonsymmetric. In combination, the evidence leads us to conclude that the current situation with most women working in part-time jobs is unlikely to be a transitional phenomenon. Partnered female part-time labor in the Netherlands is there to stay.

Notes

Sweden’s childcare system is also likely to have played an important role in this process. In 1999, Sweden’s public expenditure on formal daycare and preprimary education amounted to 1.9% of GDP, as compared with 0.6% in the Netherlands. The OECD average was 0.7% (see Jaumotte 2004). Booth and Coles (2010), using a panel of OECD data, show that public expenditure on childcare is positively correlated with female participation and with years of education.

Bussemaker (1998) provides a fascinating account of the evolution of public childcare in the Netherlands. She notes that: “Childcare provisions were not seen as part of the new [postwar] social welfare arrangements, but rather the absence of such facilities was proof of the achievement of the welfare state. While Sweden developed its childcare policies in the 1970s, in the Netherlands these were developed in the 1990s and earlier Dutch publicly financed childcare was directed only to “emergency provisions for ‘defective’ families.” Bussemaker (1998, p. 79).

There is no uniform definition of part-time work. According to OECD (2004), a part-time job is a job less than 30 h per week. Statistics Netherlands defines jobs of 12–19 h per week as small part-time jobs and job of 20–34 h per week as large part-time jobs. From 35 h per week onwards, jobs are full-time jobs. Bosch et al. (2010) use the following definitions (in hours per week): 1–11 small part-time jobs, 12–24 intermediate part-time jobs, 25–34 large part-time jobs, and ≥ 35 full-time jobs. In our data, weekly working hours of women show peaks at 20 and 32 h.

Appendix 1 contains more information about the data we use. For more information about the CentER data panel, see www.centerdata.nl/en/

In our estimates, we use k i = Σ t y it /n i , where n is the total number of observations of individual i. All observations for which y it > k i are transformed into z it = 1, all observations for which y it ≤ k i are transformed into z it = 0. Alternatively, we used z it = 1 if y it ≥ k i and z it = 0 if y it < k i . This hardly affected the parameter estimates.

As in our previous analyses for Australia and the UK, partnered health is only significant in a cross-sectional setting. This may have to do with assortative mating or common behavior (health food, exercise, etc.).

Notice that the base for our sample of partnered individuals is nonwork, and hence, it includes both nonparticipants as well as those who might be unemployed and seeking work. Readers should therefore not expect to see here the replicated results of the few other studies using a similar methodology—fixed effects ordered logit estimation—that are based on estimating subsamples of individuals who are in work or seeking work.

The parameter estimate for men in the specification without family income is −0.22 with an absolute t statistic of 1.1, while for women the parameter estimate is −0.19 (0.9). These sensitivity analyses are available from the authors on request.

Appendix 2 contains more information about the data we use. For more information about the OSA labor supply panel, see www.dans.knaw.nl/en

Although, here, we too investigated cross-partner effects, we did not find any evidence of these effects being present. The OSA data contain information about health but only since the year 2000. Therefore, we did not include health status as one of the explanatory variables. Estimated over a shorter time period, good health has a positive effect on job satisfaction for both men and women. From the sample of women, we removed the five women who worked more than 40 h per week.

Note that this is an “equilibrium” at the extensive margin of expanding or reducing working hours, as the number of preferred hours of work are not taken into account.

Incomplete specialization, in which both partners perform part of the home work and and part of the market work, may arise because of nonlinear production functions or because cost functions associated with skills investment are characterized by economies of scope. Nonlinear production functions might arise if there is activity-specific fatigue or boredom, implying diminishing marginal productivity in each activity. Cost functions characterized by economies of scope occur if investment in market skills reduces the cost of investing in home skills (see Rosen 1983). Under incomplete specialization, there will be a monotonically declining relationship between the share of house work done by one partner and that same partner’s share of market work.

The earlier Dutch Time Use Surveys did not distinguish between the housework done by each partner, although they did provide information on hours in household activities. For more information about the Dutch Time Use Surveys (TBO) see http://easy.dans.knaw.nl/dms

This type of information is not available for earlier time use surveys. Although the earlier surveys provided information on hours in household activities, they did not distinguish between the housework done by each partner.

References

Akerlof GA, Kranton RE (2000) Economics and identity. Q J Econ 115:715–753

Becker GS (1965) A theory of the allocation of time. Econ J 75:493–517

Blank RM (1989) The role of part-time work in women’s labor market choices over time. Am Econ Rev 79:295–299

Booth AL, Coles MG (2010) Tax policy and returns to education. Labour Econ 17:291–301

Booth AL, Van Ours JC (2008) Job satisfaction and family happiness: the part-time work puzzle. Econ J 118:F77–F99

Booth AL, Van Ours JC (2009) Hours of work and gender identity: does part-time work make the family happier? Economica 76:176–196

Bosch N, Deelen A, Euwals R (2010) Is part-time employment here to stay? Working hours of Dutch women over successive generations. Labour 24:35–54

Bosch N, Van der Klaauw B (2012) Analyzing female labor supply evidence from a Dutch tax reform. Labour Econ 19:271–280

Bussemaker J (1998) Rationales of care in contemporary welfare states: the case of childcare in the Netherlands. Soc Polit 5:70–96

Clark AE (1997) Job satisfaction and gender: why are women so happy at work? Labour Econ 4:341–372

Connolly S, Gregory M (2008) Moving down? Women’s part-time work and occupational change in Britain, 1991–2001. Econ J 118:F52–F76

Euwals R, Hogerbrugge M (2006) Explaining the growth of part-time employment. Labour 20:533–557

Ferrer-i-Carbonell A, Frijters P (2004) How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Econ J 114:641–659

Frey B, Stutzer A (2002) What can economists learn from happiness research? J Econ Lit 50:402–435

Herbst CM (2012) Welfare reform and the subjective well-being of single mothers. J Popul Econ doi:10.1007/s00148-012-0406-z

Jaumotte F (2004) Labour force participation of women: empirical evidence on the role of policy and other determinants in OECD countries. OECD Econ Stud 37:51–108

Manning A, Petrongolo B (2008) The part-time pay penalty for women in Britain. Econ J 114:F28–F51

OECD (2004) Employment outlook. OECD, Paris

Pérez-Asenjo E (2011) If happiness is relative, against whom do we compare ourselves? Implications for labor supply. J Popul Econ 24:1411–1442

Portegijs W, Keuzenkamp S (2008a) Nederland deeltijdland (“Netherlands parttime country”). Sociaal and Cultureel Planbureau, Den Haag

Portegijs W, Cloïn M, Keuzenkamp S, Merens A, Steenvoorden E (2008b) Verdeelde tijd; waarom vrouwen in deeltijd werken (“Divided time; why women work part-time”). Sociaal and Cultureel Planbureau, Den Haag

Rosen S (1983) Specialization and human capital. J Labor Econ 1:43–49

Sundström M (1991) Part-time work in Sweden: trends and equality effects. J Econ Issues 25:167–178

Schwarze J, Winkelmann R (2011) Happiness and altruism within the extended family. J Popul Econ 24:1033–1051

Van Praag BMS, Ferrer-i-Carbonell A (2004) Happiness quantified. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Acknowledgements

We thank CentER data and DANS (DataArchiving and Network Services) to make their data available for our research. We are grateful for the excellent research assistance of Lenny Stoeldraijer and Willemijn van den Berg and for the comment of two anonymous referees.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Erdal Tekin

Appendices

Appendix 1: Details on CentER data

The CentER-panel contains information about life satisfaction but not on job satisfaction or hours satisfaction. Our sample is restricted to married or cohabiting couples of which the female partner is between 23 and 50 in the year 1993. Also, couples with a partner older than 60 in 2006 are dropped. This leaves a sample of 3,509 observations for men and 3,449 observations for women. Table 8 gives an overview of the summary statistics for the main variables used in the analysis. Life satisfaction and health are measured from low to high on a scale from 1 to 5. Both men and women have high average scores on both variables. The distribution of working hours per week is very different for men and women. Whereas 81% of the male observations refer to work between 33 and 40 h per week, only 13% of female observations are in this working hours category. About one in three of the female observations are in the zero working hours category, while another one in three is in the category of 1–20 working hours per week. Table 8 also provides information about average net annual family income which includes labor income from both partners, about the average number of children, and the average age of the observations in our sample.

In order to establish the relationship between hours of work and life satisfaction using individual fixed effects, we need transitions of individuals between hours of work categories. Table 9 shows the transition matrix between hours of work categories in our sample. As shown for men who are in a zero working hours category, the probability to still be in this category the following year is 67.3%, while there is a 20% probability that men in the zero working hours category work in the 33–40 h per week category the next year. Clearly, for both men and women, there are many transitions between working hour categories which helps us to identify the main effects.

Appendix 2: Details on OSA data

The OSA-panel contains information about job satisfaction, hours satisfaction, and wage satisfaction. Our sample is restricted to married or cohabiting couples who are older than 23 in 1992 and younger than 60 in 2004. Also, couples with a partner older than 60 in 2004 are dropped. This leaves a sample of 6,464 observations for men and 4,301 observations for women. The job satisfaction and wage satisfaction question contains a scale from low to high from 1 to 4. For Hours satisfaction, there are three categories: the person wants to work more, the person wants to work less, or the person is satisfied about the weekly working hours. Table 10 contains an overview of the summary statistics of the relevant variables for our analysis. The table shows that both men and women score high on job satisfaction but less so on wage satisfaction. Most of the men and women in our sample are satisfied with their hours of work. Nevertheless, for about 16% of the observations workers indicate that they prefer to work longer hours, while between 22 and 26% would prefer to work fewer hours per week. In terms of actual working hours, the main category for men is 33–40 h, while for women it is 1–20 h per week. Finally, Table 10 provides information about the average number of children and the average age.

Table 11 shows the transition matrix between hours of week categories in our sample. Again, for both men and women, there are many transitions between working hours categories which helps us to identify the main effects.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Booth, A.L., van Ours, J.C. Part-time jobs: what women want?. J Popul Econ 26, 263–283 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0417-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0417-9