Abstract

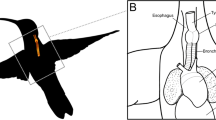

When disturbed, adults of the Death’s-head hawkmoth (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae: Acherontia atropos) produce short squeaks by drawing in and deflating air into and out of the pharynx as a defence mechanism. We took a new look at Prell’s hypothesis of a two-phase mechanism by providing new insights into the functional morphology behind the pharyngeal sound production of this species. First, we compared the head anatomy of A. atropos with another sphingid species, Manduca sexta, by using micro-computed tomography (CT) and 3D reconstruction methods. Despite differences in feeding behaviour and capability of sound production in the two species, the musculature in the head is surprisingly similar. However, A. atropos has a much shorter proboscis and a modified epipharynx with a distinct sclerotised lobe projecting into the opening of the pharynx. Second, we observed the sound production in vivo with X-ray videography, mammography CT and high-speed videography. Third, we analysed acoustic pressure over time and spectral frequency composition of six A. atropos specimens, both intact and with a removed proboscis. Single squeaks of A. atropos last for ca. 200 ms and consist of an inflation phase, a short pause and a deflation phase. The inflation phase is characterised by a burst of ca. 50 pulses with decreasing pulse frequency and a major frequency peak at ca. 8 kHz, followed by harmonics ranging up to more than 60 kHz. The deflation phase is characterised by a less clear acoustic pattern, a lower amplitude and more pronounced peaks in the same frequency range. The removal of the proboscis resulted in a significantly shortened squeak, a lower acoustic pressure level and a slightly more limited frequency spectrum. We hypothesise that the uptake of viscous honey facilitated the evolution of an efficient valve at the opening of the pharynx (i.e. a modified epipharynx), and that sound production could relatively easily have evolved based on this morphological pre-adaptation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barber JR, Kawahara AY (2013) Hawkmoths produce anti-bat ultrasound. Biol Lett 9:20130161

Beutel R-G, Friedrich F, Yang X-K, Ge S-Q (2013) Insect morphology and phylogeny: a textbook for students of entomology. De Gruyter, Berlin

Bura VL, Hnain AK, Hick JN, Yack JE (2012) Defensive sound production in the Tobacco Hornworm, Manduca sexta (Bombycoidea: Sphingidae). J Insect Behav 25:114–126

Busnel R-G, Dumortier B (1959) Vérification par des méthodes d’analyse acoustique des hypothèses sur l’origine du cri du Sphinx Acherontia atropos (Linné). Bull Soc Entomol France 64:44–58

Conner WE, Corcoran AJ (2012) Sound strategies: the 65-million-year-old battle between bats and insects. Annu Rev Entomol 57:21–39

Davis NT, Hildebrand JG (2006) Neuroanatomy of the sucking pump of the moth, Manduca sexta (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae). Arthropod Struct Dev 35:15–33

de Réaumur M (1734) Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des insectes, Vol. 1, Mém. 7, pp. 289–295

Dettner K (2003) Insekten als Nahrungsquelle, Abwehrmechanismen. In: Dettner K, Peters W (eds) Lehrbuch der Entomologie, Part 1, 2nd edn. Spektrum, Heidelberg, pp 555–599

dos Santos Rolo T, Ershov A, van de Kamp T, Baumbach T (2014) In vivo X-ray cine-tomography for tracking morphological dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:3921–3926

Dumortier B (1960) Le cri du Sphinx tête de mort. La Nature: Science-Progrès 3298:62–66

Eastham LES, Eassa YEE (1955) The feeding mechanism of the butterfly Pieris brassicae L. Philos Trans R Soc B 239:1–43

Grosse-Wilde E, Kuebler LS, Bucks S, Vogel H, Wicher D, Hansson BS (2011) Antennal transcriptome of Manduca sexta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:7449–7459

Heinrich B (1993) The hot blooded insects: strategies and mechanisms of thermoregulation. Harvard University Press, Boston

Jacobs W, Renner M (1988) Biologie und Ökologie der Insekten, 2nd edn. Fischer, Stuttgart

Kawahara AY, Mignault AA, Regier JC, Kitching IJ, Mitter C (2009) Phylogeny and biogeography of hawkmoths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae): evidence from five nuclear genes. Plos One 4, e5719

Kitching IJ (2003) Phylogeny of the death’s head hawkmoth, Acherontia [Laspeyres], and related genera (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae, Acherontiini). Syst Entomol 28:71–88

Kristensen NP (1968) The skeletal anatomy of the head of adult Mnesarchaeidae and Neopseustidae (Lep., Dacnonypha). Entomologiske Meddelelser 36:137–151

Lowe T, Garwood RJ, Simonsen TJ, Bradley RS, Withers PJ (2013) Metamorphosis revealed: time-lapse three-dimensional imaging inside a living chrysalis. J R Soc Interface 10, 20130304

Matsuda (1965) Morphology and evolution of the insect head. Mem Am Entomol Inst (Gainesville) 4:1–334

Moritz RFA, Kirchner WH, Crewe RM (1991) Chemical camouflage of the death’s head hawkmoth (Acherontia atropos L.) in honeybee colonies. Naturwissenschaften 78:179–182

Nässig W, Oberprieler RG, Duke NJ (1992) Preliminary observations on sound production in South African hawk moths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). J Entomol Soc South Afr 55:277–279

Passerini X (1828) Notes sur le cri du Sphinx à tete de mort. Ann Sci Nat 13:332–334

Prell H (1920) Die Stimme des Totenkopfes (Acherontia atropos L.). Zool Jahrb Abt Syst Geol Biol Tiere 42:235–272

Reinhardt R, Harz K (1996) Wandernde Schwärmerarten. Totenkopf-, Winden-, Oleander- und Linienschwärmer. 3rd edn. Neue Brehm-Bücherei, Westarp, Magdeburg

Scoble MJ (1992) The Lepidoptera—form, function and diversity. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Spangler HG (1987) Ultrasonic communication in Corcyra cephalonica (Stainton) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J Stored Prod Res 25:203–211

Tutt JW (1904) A natural history of the British Lepidoptera, vol 4. Swan Sonnenschein, London

Walker SM, Schwyn DA, Mokso R, Wicklein M, Müller T, Doube M et al (2014) In vivo time-resolved microtomography reveals the mechanics of the blowfly flight motor. PLoS Biol 12, e1001823

Westneat MW, Betz O, Blob RW, Fezzaa K, Cooper WJ, Lee WK (2003) Tracheal respiration in insects visualized with synchrotron X-ray imaging. Science 299:558–560

Wipfler B, Machida R, Müller B, Beutel RG (2011) On the head morphology of Grylloblattodea (Insecta) and the systematic position of the order, with a new nomenclature for the head muscles of Dicondylia. Syst Entomol 36:241–266

Zagorinsky AA, Zhantiev RD, Korsunovskaya OS (2012) The sound signals of hawkmoths (Lepidoptera, Sphingidae). Entomol Rev 92:601–604

Acknowledgments

Work on Acherontia sound was inspired by the special exhibition ‘Falten in Natur und Technik’ in the Phyletisches Museum, Friedrich-Schiller Universität Jena (2014–2015) of which it was also a part. We thank Ian Kitching (Natural History Museum, London) and Wolfgang Nässig (Senckenberg Museum, Frankfurt) for the suggestions on the literature, Stefan Franke (Ernst-Abbe-Hochschule, Jena) for supporting the acoustic analyses, Rainer Plontke (Magdala) for organising the Acherontia specimens, Sandra Niederschuh (Jena) for an introduction to the Photron camera system, Markus Knaden and Sylke Dietel-Gläßer (Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Jena) for providing the M. sexta specimens, Marion Schrumpf (Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, Jena) for help in producing Fig. 2, Vicky Kastner (Tübingen) for the linguistic improvement of the manuscript and Esther Appel (Kiel) for the critical point drying of A. atropos. Comments by four anonymous reviewers significantly helped to improve our manuscript. TK (grant KL2707/2-1) and BW (grant WI4324/1-1) are supported by the DFG.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by: Sven Thatje

Electronic supplementary material

Movie and sound files of A. atropos

ESM 1

A film (10 s length) of a manually stimulated specimen displaying a typical movement of the abdomen and squeaking three times (several days old specimen) (MP4 19042 kb)

114_2015_1292_MOESM2_ESM.wav

A sound file (4 s length) with a series of 19 consecutive squeaks after manual stimulation (freshly hatched specimen) (WAV 552 kb)

114_2015_1292_MOESM3_ESM.mov

A film (3.75 s length) of a consecutive series of 15 mammography X-ray images recorded at 4 frames s−1. The rapid expansion and collapse of the pharynx is visible (MOV 2687 kb)

114_2015_1292_MOESM4_ESM.mov

The compilation of a film (total: 9 min 14 s length) of a specimen in a micro CT, recorded at 1.83 frames s−1. The specimen was electrically stimulated every ca. 60 s. A reaction was visible after stimulation 1, 6, 7 and 8. Stimulation 1 and 6: The pharynx rapidly inflates and deflates. Stimulation 7: the pharynx is inflated and remains semi-inflated until stimulation 8. Note that further reactions could easily have been missed because of the low time resolution (MOV 31370 kb)

114_2015_1292_MOESM5_ESM.mp4

A film (1.38 s length) recorded at 2000 frames s−1. Start at 1863 ms with closed mouth, mouth opens at 1913–1970 ms, stimulus is given at ca. 2650 ms, visible reaction after electric stimulation starts at 2660 ms, head is moved upwards, (air is drawn in), hemolymph fluid visible (air is deflated) from ca. 2820 ms. Stop at 3240 ms. Time between stimulus and visible deflation is thus ca. 170 ms (MP4 14835 kb)

Excel spreadsheet with raw data of acoustic measurements

ESM 2

Overview measurements and results (XLS 39 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brehm, G., Fischer, M., Gorb, S. et al. The unique sound production of the Death’s-head hawkmoth (Acherontia atropos (Linnaeus, 1758)) revisited. Sci Nat 102, 43 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-015-1292-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-015-1292-5