Abstract

Policy proposals to balance the budget and to limit government spending assume that budget deficits cause substantial harm, either increasing inflation or crowding out private borrowing from credit markets. These assertions have the support of policymakers across the breadth of the political spectrum, and dominate current political debate on macroeconomic policy. However, macroeconomic theory fails to provide a clearcut causal connection between budget deficits and larger economic problems such as inflation and recession. Thus, policies could be enacted that attack the symptoms instead of the causes of the deficit.

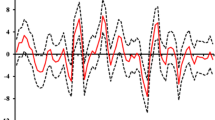

We use the Granger causality test to find the causal relationships between budget deficits and inflation, GNP, and private investment respectively, for seventeen OECD countries for the period 1949–1981. Deficits do not cause changes in these variables; rather there is weak evidence that inflation and recession cause deficits. This implies that deficits are a symptom rather than a cause of inflation and reduced national output. So, if our goal is to reduce inflation and increase output, we should look to more direct policies than reducing deficits.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Alperovitz, Gar (1983). “Let's spend our way into real recovery,” Washington Post (July 17).

Anderson, J. W. (1982). “Pain by the numbers,” Washington Post (April 4).

Barro, Robert J. (1974). “Are government bonds net wealth?” Journal of Political Economy 82: 1095–1117.

Berry, John M. (1983). “Are high deficits the cause or the cure of an ailing economy?” Washington Post (January 23).

Boskin, Michael J. (1982). “Macroeconomic versus microeconomic issues in the federal budget,” in Michael J. Boskin and Aaron Wildavsky (eds.), The Federal Budget: Economics of Politics. San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies, pp. 111–131.

Boyd, Robert S. (1982). “Government sets record with $ 110 billion deficit,” Miami Herald (October 27).

Congressional Budget Office (1982a). “The Prospects for Economic Recovery - Part I.” Washington DC: Government Printing Office.

Congressional Budget Office (1982b). “Balancing the Federal Budget and Limiting Federal Spending: Constitutional and Statutory Approaches.” Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Congressional Budget Office (1983a). “Reducing the Deficit: Spending and Revenue Options.” Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Congressional Budget Office (1983b). “The Economic and Budget Outlook: An Update.” Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Council of Economic Advisors (1984). Economic Report of the President. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Downs, Anthony (1967). Inside Bureaucracy. Boston: Little, Brown.

Dwyer, Gerald D. (1982). “Inflation and government deficits,” Economic Inquiry 20: 315–329.

Eisner, Robert (1984). “Which budget deficit: Some issues of measurement and their implications,” American Economic Review (May).

Freeman, John (1983). “Granger causality and time series analysis of political relationships,” American Journal of Political Science 27: 327–358.

Frey, Bruno S. and Friedrich Schneider (1978). Modern Political Economy. New York: Halsted Press.

Friedman, Benjamin M. (1982). “A Credit Market Perspective on the U.S. Government Deficit Problem 1982–87,” Harvard Institute of Economic Research, Discussion Paper #948.

Fuerbringer, Jonathan (1982). “Ways to look at deficit vary,” New York Times (November 30).

Granger, C. W. J. (1969). “Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods,” Econometrica 37: 424–438.

Guilkey, David K. and Michael K. Salemi (1982). “Small sample properties of three tests for Granger causal ordering in a bivariate stochastic system,” Review of Economics and Statistics 64: 668–706.

Heller, Walter W. (1983). “Feldstein's right: Don't blame Congress,” Wall Street Journal (December 19).

Hoelscher, Gregory P. (1983). “Federal borrowing and short-term interest rates,” Southern Economic Journal 50: 319–333.

International Monetary Fund. International Financial Statistics, various years.

Kmenta, Jan (1971). Elements of Econometrics. New York, Macmillan.

Kraft, Joseph (1982). “Here's how to find villain in high interest rates,” The Miami Herald (July 12).

Learner, Edward (1983). “Let's take the con out of econometrics,” American Economic Review 73: 31–43.

McDermott, John (1982). “The great escape: The secret history of the deficit,” The Nation (August 21–28) 235: 129, 144–146.

Miami Herald (1982). “Don't undercut the Fed” (November 16).

Miami Herald (1983). “U.S. budget deficit returns to haunt” (January 23).

Miami Herald (1983). “Federal deficits may ruin recovery, analysts warn” (April 6).

Niskanen, William (1978). “Deficits, government spending and inflation,” Journal of Monetary Economics 4: 591–602.

Ornstein, Norman J. (1982a). “They're breaking the law by breaking the budget,” Washington Post (August 22).

Ornstein, Norman J. (1982b). “The painless balanced budget: Stockman has given us an instant, legitimate way into the black,” Washington Post (September 26).

Penner, Rudolph G. (1982). “Forecasting budget totals: Why can't we get it right?”, in Michael J. Boskin and Aaron Wildavsky (eds.), The Federal Budget: Economics of Politics. San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies, pp. 89–110.

Quayle, Dan (1982). “The budget deficit is unacceptable,” Miami Herald (February 14).

Samuelson, Robert J. (1982). “Deficits and saving,” National Journal (February 20) 14: 339.

Solow, Robert M. (1980). “All simple stories about inflation are wrong,” Washington Post (May 18).

Thurow, Lester (1980). The Zero-Sum Society. New York: Basic Books.

Tobin, James (1982). “Stop Volcker from killing the economy,” Washington Post (August 15).

Tobin, James (1980). “Asset Accumulation and Economic Activity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tobin, James and William Buiter (1980). “Fiscal and monetary policies, capital formation and economic activity,” in George M. von Furstenberg (ed.), The Government and Capital Formation. Cambridge: Ballinger.

Ullman, Owen (1984). “Reagan's 1985 budget,” Miami Herald (February 2).

The Wall Street Journal (1982). “A bi-partisan appeal to resolve the budget crisis” (January 25).

Wanniski, Jude (1982). “The balanced budget amendment: The idea is ludicrous,” Washington Post (August 1).

Wildavsky, Aaron (1980). How to Limit Government Spending. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Wojnilower, Albert M. (1983). “The bogus issue of the deficit,” New York Times (December 4).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guess, G., Koford, K. Inflation, recession and the federal budget deficit (or, blaming economic problems on a statistical mirage). Policy Sci 17, 385–402 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138402

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138402