Abstract

Background

Adverse events related to analgesic use represent a challenge for optimizing treatment of pain in older people.

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine whether non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NS-NSAID) and cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor use is appropriately targeted in those with a prior history of gastrointestinal (GI) events, myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke.

Methods

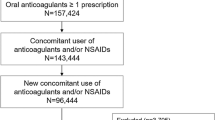

A retrospective study of pharmacy claims data from the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs was conducted, involving 288,912 veterans aged 55 years and over. Analgesic utilization from 2007 to 2009 was assessed. Three risk cohorts (veterans with prior hospitalization for GI bleed, MI or stroke) and a low-risk cohort were identified. Poisson regression was applied to test for a linear trend over the study period.

Results

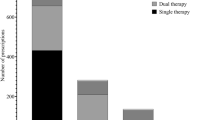

The prevalence of analgesics dispensed in the overall study population was approximately 34 % between 2007 and 2009. COX-2 inhibitors were more widely dispensed than NS-NSAIDs in all those at risk of NSAID-related adverse events. At the end of 2009, the ratio was 5.1 % to 2.5 % in the GI cohort, 3.6 % to 3.2 % in the MI cohort and 3.6 % to 2.6 % in the stroke cohort.

Conclusions

Although COX-2 inhibitors appeared to be preferred over NS-NSAIDs in those with a prior history of GI events, 2.5 % of patients were still using an NS-NSAID at the end of the study period. Consistent with treatment guidelines, in most of these cases, these drugs were co-dispensed with proton pump inhibitors. COX-2 inhibitors were used at slightly higher rates than NS-NSAIDs in those with a prior history of MI or stroke, which is not consistent with guidelines recommending NS-NSAID use.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schnitzer TJ. Update on guidelines for treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25(Suppl. 1):S22–9.

Therapeutic Goods Administration, Department of Health and Ageing. Expanded information on Cox-2 inhibitors for doctors and pharmacists. Department of Health and Ageing. 2005. http://www.tga.gov.au/archive/media-2005-cox2-050210.htm. Accessed 24 Jan 2012.

European Medicines Agency. Scientific conclusions for the amendment of the marketing authorisation—COX-2 inhibitors. European Medicines Agency. 2005. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Referrals_document/Celecoxib_31/WC500012417.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2012.

Food and Drug Administration. COX-2 selective (includes Bextra, Celebrex, and Vioxx) and Non-Selective Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). Food and Drug Administration. 2005. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm103420.htm. Accessed 24 Jan 2011.

Andersohn F, Suissa S, Garbe E. Use of first- and second-generation cyclooxygenase-2-selective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and risk of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006;113(16):1950–7.

Bombardier C, Laine L, Reicin A, et al. Comparison of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of rofecoxib and naproxen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. VIGOR Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(32):1520–8.

Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, et al. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1092–102.

Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, et al. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1071–80.

McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk and inhibition of cyclooxygenase: a systematic review of the observational studies of selective and nonselective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase 2. JAMA. 2006;296(13):1633–44.

Hernández-Díaz S, Varas-Lorenzo C, García Rodríguez LA, et al. Non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98(3):266–74.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System. Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Norwegian Institute of Public Health. 2012. http://www.whocc.no/atcddd/. Accessed 21 May 2012.

Warner TD, Mitchell JA. Cyclooxygenases: new forms, new inhibitors, and lessons from the clinic. FASEB J. 2004;18(7):790–804.

Ray WA, Varas-Lorenzo C, Chung CP, et al. Cardiovascular risks of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in patients after hospitalization for serious coronary heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(3):155–63.

Motsko SP, Rascati KL, Busti AJ, et al. Temporal relationship between use of NSAIDs, including selective COX-2 inhibitors, and cardiovascular risk. Drug Saf. 2006;29(7):621–32.

Hernández-Díaz S, Rodríguez LA. Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/perforation: an overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990s. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2093–9.

Moore RA, Derry S, Makinson GT, et al. Tolerability and adverse events in clinical trials of celecoxib in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of information from company clinical trial reports. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(3):R644–65.

Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, et al. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: the CLASS study: a randomized controlled trial. Celecoxib Long-term Arthritis Safety Study. JAMA. 2000;284(10):1247–55.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guideline for the non-surgical management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Melbourne: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2009.

Rheumatology Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: rheumatology. Version 1. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2006.

Analgesic Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: analgesics. Version 5. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2007.

Gastroenterological Society of Australia, Digestive Health Foundation. NSAIDs and the Gastronitestinal Tract. Mulgrave: The Gastroenterological Society of Australia; 2009.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: summary of results, 2007–2008. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2010.

Barkin RL, Beckerman M, Blum SL, et al. Should nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) be prescribed to the older adult? Drugs Aging. 2010;27(10):775–89.

Roughead EE, Ramsay E, Pratt N, et al. NSAID use in individuals at risk of renal adverse events: an observational study to investigate trends in Australian veterans. Drug Saf. 2008;31(11):997–1003.

Lloyd J, Anderson P, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Veterans’ use of health services. Canberra: AIHW; 2008.

Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Treatment population statistics December 2011. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs; 2011.

Australian Government Department of Human Services. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). Canberra: Australian Government Department of Human Services, 2011. http://www.medicareaustralia.gov.au/provider/pbs/index.jsp. Accessed 20 Apr 2012.

National Centre for Classification in Health. The international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision, Australian modification (ICD-10-AM). 6th ed. Sydney: National Centre for Classification in Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney; 2005.

National Prescribing Service Limited. Analgesic choices in persistent pain. Report No.: 35. Sydney: National Prescribing Service Limited; 2006.

Therapeutic Goods Administration, Department of Health and Ageing. Regulator takes tough action on arthritis drugs (*amended). Woden: Department of Health and Ageing, 2005. http://www.tga.gov.au/archive/media-2005-arthritis-050210.htm. Accessed 24 Jan 2012.

Palliative Care Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: palliative care. Version 3. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd; 2010.

Reville B, Axelrod D, Maury R. Palliative care for the cancer patient. Prim Care. 2009;36(4):781–810.

Morgan TK, Williamson M, Pirotta M, et al. A national census of medicines use: a 24-hour snapshot of Australians aged 50 years and older. Med J Aust. 2012;196(1):50–3.

Hudec R, Božeková L, Tisoňová J. Consumption of three most widely used analgesics in six European countries. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37(1):78–80.

Fosbøl EL, Gislason GH, Jacobsen S, et al. The pattern of use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) from 1997 to 2005: a nationwide study on 4.6 million people. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(8):822–33.

Donnelly N, McManus P, Dudley J, et al. Impact of increasing the re-supply interval on the seasonality of subsidised prescription use in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000;6(24):603–6.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population by age and sex, Australian states and territories, June 2010. Contract no.: ABS cat. no. 3201.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2010.

Acknowledgments

Svetla Gadzhanova and Elizabeth E. Roughead were responsible for study design. Svetla Gadzhanova, Jenni Ilomäki and Elizabeth E. Roughead were responsible for the analyses, interpretation of the results and preparation of the manuscript. This study was funded by NPS Better choices Better health. The authors wish to thank Mark Bartlett from NPS for his comments on the manuscript. We acknowledge the support of the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs, which provided data for the conduct of these analyses. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gadzhanova, S., Ilomäki, J. & Roughead, E.E. COX-2 Inhibitor and Non-Selective NSAID Use in Those at Increased Risk of NSAID-Related Adverse Events. Drugs Aging 30, 23–30 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-012-0037-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-012-0037-9