Abstract

Background

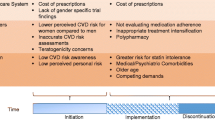

Pharmacotherapy with statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) is the cornerstone for lipid management in individuals with or at risk of developing cardiovascular diseases. Although the clinical benefits of statins are established for both women and men, there is evidence of a gender difference in their use. The current study extends prior scientific research by estimating the extent to which individual-level variables may explain gender differences in statin use by using a post-regression non-linear decomposition technique.

Objective

The objective of this study was to estimate the magnitude of gender differences in statin use among the elderly and examine individual-level variables that can explain the gender differences in statin use among elderly individuals with or at risk of cardiovascular diseases.

Methods

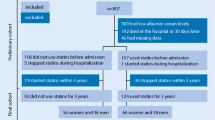

A retrospective cross-sectional study design was adopted. Data were derived from the 2005 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), a nationally representative survey of Medicare beneficiaries in the US. The analytic study sample consisted of community-dwelling elderly Medicare beneficiaries, aged 65 years or older, who had reported any of the following conditions: heart disease, hyperlipidaemia or diabetes mellitus, and who were alive during the observation year. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate the unadjusted associations between gender and statin use for each of the characteristics. Multivariate logistic regressions were used to evaluate the relationship between gender and statin use. A post-regression non-linear decomposition approach was used to understand individual-level variables that could explain gender differences in statin use.

Results

Among 5,508 elderly, 47.2 % of the women and 55.5 % of the men reported any statin use in 2005, which translates to an 8.3 percentage point difference in statin use. In the multivariate logistic regression on statin use, women were 21 % less likely than men to use statins (adjusted odds ratio = 0.79; 95 % CI 0.69, 0.89). Post-regression non-linear decomposition analysis revealed that of the 8.3 percentage point difference in statin use, 29.5 % was explained by the individual-level variables. Lifestyle risk factors accounted for most of the explained portion of the gender difference in statin use.

Conclusions

Among elderly Medicare beneficiaries, women were less likely than men to report any use of statins. Less than one third of the total gender difference in statin use was attributed to individual-level variables such as demographics, economic status, physical health status, depression and lifestyle risk factors. Further research is needed to identify whether provider and/or organizational-level factors can further explain the gender difference in statin use.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Braga MB, Langer A, Leiter LA. Recommendations for management of dyslipidemia in high cardiovascular risk patients. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2008 Summer;13(2):71–4.

Walsh JM, Pignone M. Drug treatment of hyperlipidemia in women. JAMA. 2004;291(18):2243–52.

LaRosa JC, He J, Vupputuri S. Effect of statins on risk of coronary disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1999;282(24):2340–6.

Mills EJ, Rachlis B, Wu P, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular mortality and events with statin treatments: a network meta-analysis involving more than 65,000 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(22):1769–81.

Miettinen TA, Pyorala K, Olsson AG, Musliner TA, Cook TJ, Faergeman O, et al. Cholesterol-lowering therapy in women and elderly patients with myocardial infarction or angina pectoris: findings from the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Circulation. 1997;96(12):4211–8.

Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9326):7–22.

Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, Bollen EL, Buckley BM, Cobbe SM, PROSPER study group. PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk, et al. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1623–30.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, Coordinating Committee of the National Cholesterol Education Program, et al. A summary of implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(8):1329–30.

LaRosa JC. Outcomes of lipid-lowering treatment in postmenopausal women. Drugs Aging. 2002;19(8):595–604.

Stagnitti MN. Statin use among persons 18 and older in the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population reported as receiving medical care for the treatment of high cholesterol, 2002. MEPS Statistical Brief #95. http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st95/stat95.pdf. Accessed 27 Jul 2011.

Pambianco G, Lombardero M, Bittner V, et al. Control of lipids at baseline in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) trial. Prev Cardiol. 2009 Winter; 12(1):9–18.

Franks P, Tancredi D, Winters P, et al. Cholesterol treatment with statins: who is left out and who makes it to goal? BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):68.

Segars LW, Lea AR. Assessing prescriptions for statins in ambulatory diabetic patients in the United States: a national, cross-sectional study. Clin Ther. 2008;30(11):2159–66.

Mann D, Reynolds K, Smith D, Muntner P. Trends in statin use and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels among US adults: impact of the 2001 National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(9):1208–15.

Cooke CE, Hammerash WJ Jr. Retrospective review of sex differences in the management of dyslipidemia in coronary heart disease: an analysis of patient data from a Maryland-based health maintenance organization. Clin Ther. 2006;28(4):591–9.

Akhter N, Milford-Beland S, Roe MT, Piana RN, Kao J, Shroff A. Gender differences among patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC-NCDR). Am Heart J. 2009;157(1):141–8.

Enriquez JR, Pratap P, Zbilut JP, Calvin JE, Volgman AS. Women tolerate drug therapy for coronary artery disease as well as men do, but are treated less frequently with aspirin, beta-blockers, or statins. Gend Med. 2008;5(1):53–61.

Cho L, Hoogwerf B, Huang J, Brennan DM, Hazen SL. Gender differences in utilization of effective cardiovascular secondary prevention: a Cleveland clinic prevention database study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(4):515–21.

Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, et al. Ten-year trends of cardiovascular drug use after myocardial infarction among community-dwelling persons ≥65 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(7):1061–7.

Robinson JG, Booth B. Statin use and lipid levels in older adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001 to 2006. J Clin Lipidol. 2010;4(6):483–90.

Vimalananda VG, Miller DR, Palnati M, et al. Gender disparities in lipid-lowering therapy among veterans with diabetes. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(4 Suppl):S176–81.

Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009 Jan 27;119(3):e21–181. Epub 2008 Dec 15. Erratum in: Circulation. 2010;122(1):e11.

Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, et al. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56(10):1–120.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Health data interactive. Data sources. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/hdi/hdi_data_sources.htm. Accessed 20 Jul 2011.

Eppig FJ, Chulis GS. Matching MCBS (Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey) and Medicare data: the best of both worlds. Health Care Financ Rev. 1997 Spring;18(3):211–29.

Pollak VE, Lorch JA. Effect of electronic patient record use on mortality in end stage renal disease, a model chronic disease: retrospective analysis of 9 years of prospectively collected data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:38.

Perez A, Anzaldua M, McCormick J, Fisher-Hoch S. High frequency of chronic end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma in a Hispanic population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19(3):289–95.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Prior HHS poverty guidelines and Federal Register references. http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/figures-fed-reg.shtml. Accessed 10 Aug 2011.

Sambamoorthi U, Akincigil A, Wei W, et al. National trends in out-of-pocket prescription drug spending among elderly medicare beneficiaries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2005;5(3):297–315.

Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Walkup JT, Akincigil A. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trends. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(12):1718–28.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Healthy weight – it’s not a diet, it’s a lifestyle! About BMI for adults. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html. Accessed 14 Aug 2011.

Johnson RW, Sambamoorthi U, Crystal S. Gender differences in pension wealth: estimates using provider data. Gerontologist. 1999;39(3):320–33.

Sambamoorthi U, Olfson M, Walkup JT, et al. Diffusion of new generation antidepressant treatment among elderly diagnosed with depression. Med Care. 2003;41(1):180–94.

Tseng CL, Sambamoorthi U, Rajan M, et al. Are there gender differences in diabetes care among elderly Medicare enrolled veterans? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 Suppl 3:S47–53.

Fairlie RW. An extension of the Blinder–Oaxaca decomposition technique to logit and probit models. J Econ Soc Meas. 2005;30(4):305–16.

Fairlie RW. The absence of the African American owned business: an analysis of the dynamics of self-employment. J Labor Econ. 1999;17(1):80–108.

Oaxaca R. Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int Econ Rev. 1973;14(3):693–709.

Neumark D. Employers’ discriminatory behavior and the estimation of wage discrimination. J Hum Resour. 1988;23(3):279–95.

Oliver-Mcneil S, Artinian NT. Women’s perceptions of personal cardiovascular risk and their risk-reducing behaviors. Am J Crit Care. 2002;11(3):221–7.

Mosca L, Ferris A, Fabunmi R, American Heart Association. Tracking women’s awareness of heart disease: an American Heart Association national study. Circulation. 2004;109(5):573–9.

Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Hayes SN, Walsh BW, et al. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation. 2005;111(4):499–510.

Cook NL, Ayanian JZ, Orav EJ, Hicks LS. Differences in specialist consultations for cardiovascular disease by race, ethnicity, gender, insurance status, and site of primary care. Circulation. 2009;119(18):2463–70.

McAlister FA, Majumdar SR, Eurich DT, Johnson JA. The effect of specialist care within the first year on subsequent outcomes in 24,232 adults with new-onset diabetes mellitus: population-based cohort study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):6–11.

Ellis JJ, Erickson SR, Stevenson JG, Bernstein SJ, Stiles RA, Fendrick AM. Suboptimal statin adherence and discontinuation in primary and secondary prevention populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):638–45.

Keddissi JI, Younis WG, Chbeir EA, et al. The use of statins and lung function in current and former smokers. Chest. 2007;132(6):1764–71.

Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, Daley J, Deedwania PC, Douglas JS, American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina), et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina–summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Chronic Stable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(1):159–68.

Hall-Lipsy EA, Chisholm-Burns MA. Pharmacotherapeutic disparities: racial, ethnic, and sex variations in medication treatment. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67(6):462–8.

Acknowledgments

Mr Bhattacharjee received research assistance and Dr Sambamoorthi was partially supported for infrastructure from the West Virginia Collaborative Health Outcomes Research of Therapies and Services (WV CoHORTS) Center (Morgantown, WV, USA). The authors would also like to thank Dr Joel Halverson for his inspiration and encouragement in conducting this study. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bhattacharjee, S., Findley, P.A. & Sambamoorthi, U. Understanding Gender Differences in Statin Use among Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries. Drugs Aging 29, 971–980 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-012-0032-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-012-0032-1