Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of the present study is to determine in what way a conventional versus a modern medical curriculum influences teaching delivery in formal radiology education.

Methods

A web-based questionnaire was distributed by the ESR to radiology teaching staff from 93 European teaching institutions.

Results

Early exposure to radiology in pre-clinical years is typically reported in institutions with a modern curriculum. The average number of teaching hours related to radiology is similar in both curriculum types (60 h). Radiology in modern curricula is mainly taught by radiologists, radiology trainees (50%), radiographers (20%) or clinicians (17%). Mandatory clerkships are pertinent to modern curricula (55% vs. 41% conventional curriculum), which start in the first (13% vs. 4% conventional curriculum) or second year of the training (9% vs. 2% conventional curriculum). The common core in both curricula consists of radiology examinations, to work with radiology teaching files, to attend radiology conferences, and to participate in multidisciplinary meetings.

Conclusion

The influence of a modern curriculum on the formal radiology teaching is visible in terms of earlier exposure to radiology, involvement of a wider range of staff grades and range of profession involved in teaching, and radiology clerkships with more active and integrated tasks.

Main Message

• This study looks at differences in the nature of formal radiology teaching.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is constant debate about trends in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education within the framework of curriculum changes [1, 2], curriculum reforms [3], and as a result of the adoption of the Bachelor’s-Master structure in medical education (the Bologna Two-Cycle System) [4, 5]. During the past century, three generations of educational reforms can be distinguished.

Curricula of the first generation were launched at the beginning of the 20th century and mainly focused on a science-based curriculum [6]. More specifically, this conventional medical curriculum consists of a pre-clinical and a clinical part, in which instruction is based on disciplines like anatomy, physiology, histology, internal medicine, surgery, pharmacology, etc., and radiology. Assessment is linked to these individual disciplines and spread over 1 or more curriculum years. In this type of curriculum, radiology is usually studied and assessed in the clinical part where it is linked to the imaging of diseases. Radiology is sometimes present (as an extra) in anatomy courses.

Around the mid-20th century, medical curricula of the second generation introduced problem-based instruction [6]. In problem-based curricula, the building blocks are part of both the pre-clinical and clinical part of the curriculum. Instruction is based on comprehensive “modules” covering systems or parts of the body like the thorax, abdomen, musculoskeletal system, nervous system, urogenital system, etc. Usually these modules cover “the healthy human” during the preclinical years and the “patient” during clinical years. In the pre-clinical phase, disciplines—including radiology—are combined to develop an understanding of different healthy human systems (e.g., the gastrointestinal system), until the whole “healthy” body has been covered. In the clinical phase, additional disciplines like internal medicine, surgery, pharmacology, radiology, etc., are interconnected. Each module is concluded with an examination that focuses on the integrated mastery of the disciplines covered in this module.

In the third generation, outcome-based education is now being introduced that aims at improving the performance of health systems by adapting core professional competencies related to specific contexts, while drawing on a generic knowledge base [6]. This stresses the importance of inter-professional, multidisciplinary education and the abolition of traditional boundaries between professions as well as the necessity for a greater transparency of the educational program. Also, a stronger international recognition of diplomas and mobility within Europe can be perceived; see, e.g., the impact of the Bologna Two-Cycle System [4, 5, 7, 8], the establishment and implementation of a European Credit Transfer System [7, 9], and the internationalization of medical education [6, 10, 11].

European radiology teaching and research are affected by these worldwide curriculum innovations that move away from a conventional (science-based) curriculum toward a modern curriculum (i.e., problem-based and outcomes-based curriculum) as confirmed in a first European benchmark study that was carried out in 2008. One of the objectives of this research was to study the curriculum impact of innovations in the medical curriculum on radiology teaching and research [12]. However, a follow-up study was considered necessary to deal with a number of limitations of the former survey.

This article centers on the influence of the type of medical curriculum—i.e., a conventional curriculum vs. a modern curriculum such as problem-based learning (PBL), modular type, hybrid type—on the nature of formal teaching in radiology education. The next indicators are focused upon to describe the influences:

-

1.

The type of radiology courses.

-

2.

The presence of radiology throughout the different years of medical training.

-

3.

The proportion of the curriculum focusing on radiology teaching: the total number of the teaching hours focusing on formal radiology teaching.

-

4.

The use and the type of e-learning in radiology teaching.

-

5.

The involvement of specific teaching staff in radiology teaching.

-

6.

The place of radiology clerkships within the curricula and the tasks students carry out during the clerkships.

Materials and methods

A survey study was set up under the umbrella of the Educational Committee of the European Society of Radiology (ESR). In this context, a questionnaire was electronically distributed to the 430 heads of academic radiological departments in Europe. For each institution, one single questionnaire was filled out by both the radiology teaching staff and the chiefs of the teaching hospitals. In total, questionnaires were returned from 93 European teaching institutions, representing 27 countries. Each country was presented by one or more teaching institutions (Appendix 1).

The questionnaire (Appendix 2) was partly based on a previous study that provided a first panoramic view on how radiology teaching is organized in European medical educational curricula [12]. The latter questionnaire was extended with additional multiple-choice items about, e.g., the place of radiology courses within the medical curriculum, and the use and type(s) of e-learning in radiology teaching. The section about radiology clerkships was extended with items about the types of a radiology clerkship (an obligatory or an elective) and the nature of the tasks students carry out during the clerkship.

Statistical analysis

The questionnaire data were entered and analyzed with SPSS version 15 software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; Chicago, IL, USA). Mainly descriptive statistics were applied and a variety of tools to develop graphical representations of the results.

Results

The responses of the 93 European institutions can be split up into two groups regarding the nature of their medical curriculum: programs reflecting a conventional medical curriculum (47 institutions, 50.5%) versus programs that adopt a modern medical curriculum that is problem based, hybrid, integrated, or modular (46 teaching centers, 49.5%). This distinction in curricula types will be applied when comparing the impact on formal radiology teaching delivery.

The types of radiology courses within conventional and modern medical curricula

Within conventional medical curricula, the radiology course is mostly a mandatory building block (87%), sometimes an elective course (6%), or a combination of both (6%). In modern curricula, radiology is to a lesser extent a mandatory building block (70%), an elective course (9%), or a combination of both (22%).

The presence of radiology in different medical training years

Radiology is consistently a part of the medical curriculum in every medical training year in institutions that adopt a modern curriculum approach. Figure 1 clearly illustrates that students in 41% of the modern curricula receive their first radiology experience during the first year of medical training, versus only 2% in institutions adopting a conventional curriculum. The second year and the sixth year of the training are again very important for radiology teaching within a modern curriculum (65% vs. 6% for the 2nd year and 50% vs. 2% for the 6th year, respectively). The attention paid to radiology teaching in the third, fourth, and fifth year of medical training seems to be equally important in both modern and conventional curricula.

The proportion of the curriculum focusing on radiology teaching (the total numbers of teaching hours)

The proportion of the curriculum focusing on radiology teaching is comparable in conventional and modern types of curricula. The average total number of teaching hours focusing on radiology within conventional curricula is 65 h (SD 24, median 66, minimum 20 and maximum 120), and in modern curricula it is 63 h (SD 33, median 59, minimum 9, and maximum 146). We observed no significant difference (t = 0,25; df = 81,4; p = 0,801).

The use and types of e-learning in radiology teaching

More than 70 percent of the European institutions reported the use of e-learning during radiology teaching [34 centers (72%) within conventional curricula and 35 centers (76%) within modern curricula]. Figure 2 shows the types of the e-learning used within both curricula. Striking is the large usage of educational radiology software in modern medical curricula (32% vs. 11%) and the dominant teaching via PACS or web-based PACS in the conventional curricula (38% vs. 26%). The use of the Internet seems to be popular within both types of curricula.

Involvement of a teaching staff in radiology teaching

The average number of radiology-related teaching staff is eight in a conventional curriculum and 15 in a modern curriculum. Radiology—in both curricula types—is preferably taught by general radiologists as shown in Fig. 3. It is apparent that within modern curricula, other medical teachers participate in the teaching process such as sub-specialized radiologists (98%), clinicians (17%), and radiographers (20%). Also the involvement of radiology trainees during radiology teaching is observed to a larger extent in modern curricula (50% vs. 28%).

The place of radiology clerkships within curricula and the nature of the tasks students carry out during clerkships

In this new study, special attention was paid to the types and the position of the radiology clerkships (or “practical sessions”) within a medical curriculum (Fig. 4). In more than half of the institutions adopting a modern medical curriculum, the clerkships are mandatory (55%), while 59% of institutions adopting a conventional curriculum reported that radiology clerkships were an elective part of the curriculum. The curriculum position of radiology clerkship is more visible within a modern curriculum. The possibility is made available to visit a radiology department in the first (13% vs. 4%) or second year of the training (9% vs. 2%). Clerkships in the fourth year of the medical training are critical in both curricula (61% vs. 45%), though again more dominant in modern curricula. The average duration of a radiology clerkship during the entire medical training is 5.1 weeks in a conventional curriculum and 4.4 weeks in a modern curriculum. But in the latter case, radiology clerkships are spread over more curriculum years.

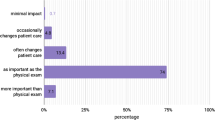

The tasks that students carry out during the clerkships are represented in Fig. 5. It is clear that in both curricula observational tasks are dominant (83% vs. 70%). It is also apparent that “active” tasks, such as to follow radiological examinations (83% vs. 70% respectively) or to work with radiology teaching files (37% vs. 28%), gets more space within a modern curriculum. Also, integrated tasks such as attending radiology conferences (74% vs. 47%) or participating in a multidisciplinary meeting (52% vs. 26%) are more established within a modern curriculum. To work with radiology CDs seems to be more common in a conventional curriculum (23% vs. 15%).

Discussion

As stated in the introduction session, in the medical literature reviewing the status and innovations of medical curriculum, the main focus is on the curriculum shift from a first generation curriculum (e.g., conventional curriculum) to a second (e.g., problem-based) and a third generation curriculum (e.g., competence-based). In this context recent research points at the importance of radiology within the medical curriculum [13] and calls for the improvement of radiology education [14]. The current analysis of the present situation in Europe regarding formal radiology undergraduate teaching shows some clear trends. One of the optimistic findings is that within both conventional and modern medical curricula, radiology courses are mostly present as mandatory courses. The situation in Europe seems to differ from the US and Canada where radiology is rather present as an elective course [15, 16]. Also, radiology seems to be a consistent part of the medical curriculum in every medical training year. This is an important observation in view of the effect of the exposure on the students' beliefs about radiology and their future career choice [17]. From the present study, it becomes clear that one of the advantages of a modern type of curriculum (i.e., problem based, hybrid, integrated, modular) is the fact that students already get their first radiology experience during the first year of medical training. Also the second year and the sixth year of the training seem to be important within modern curricula, while the conventional curriculum rather emphasizes radiology teaching in the third and fourth year of the training. Year 6 radiology exposure might be important to influence decisions of students to adopt radiology as a career choice.

Although the proportion of the curriculum focusing on radiology is comparable in both types of the curriculum, the involvement of radiology-related teaching staff is considerably higher in modern curricula (15 vs. 8 teachers). The fact that within modern curricula more teachers and also other medical specialists participate in the teaching and learning process (i.e., sub-specialized radiologists, clinicians, and radiographers) can be explained by the stronger multidisciplinary teaching focus that stresses the linkages between and integration of medical disciplines [18]. However, the results reiterate the findings of previous research that radiology is preferably taught by general radiologists [12] that are considered as successful educators [17, 19, 20].

The fact that specialized radiologists are involved in teaching is favored in the literature but might also be a point of concern [21, 22]. Attention should be paid to the adequate level of radiology teaching. There is a risk that specialized radiologists teach at a too high level and prefer to focus on rare diseases and advanced techniques, thus forgetting about first line radiology. In the literature it is stressed that teaching staff needs to adopt a consistent educational approach: compatible teaching methods, clear learning objectives pursued throughout the different curriculum years and taking into account the progressive level in radiology competences of undergraduate students [13].

Also, the involvement of radiology trainees in radiology teaching is more prominent in modern curricula (50% vs. 28%). It is important to keep in mind that attention should be paid to adequate training to improve teaching skills. Formal instruction, based on effective teaching methods, is critical for resident teachers. Also, effective support and development opportunities should be provided [23–25].

The expanded use of multimedia [26–28] and e-learning (radiology software and Internet usage) [27, 29–35] as part of the didactical approach in radiology teaching can be expected to foster effective learning. Also, from the student perspective, e-learning is a highly appreciated component of an innovative radiology curriculum [36]. The results of the present study are in line with previous research and show clear differences in the types of e-learning implemented within a conventional and a modern curriculum. Educational radiology software is typically found in modern medical curricula. Teaching based on PACS or web-based PACS is typically found in conventional curricula. However, the use of the Internet is popular within both types of curricula.

Clinical clerkships are reported in the literature as a vital part of a radiology curriculum [21, 37–39]. Previous European research supports this finding [12]. By considering the limitations of a first benchmarking study, the present study paid special attention to the types and the position of the radiology clerkships (or “practical sessions”) within the medical curriculum. Our finding that in more than half of the modern medical curricula a clerkship is a mandatory activity is positive and promising. In this way, modern medical curricula underpin the finding of previous research that considers radiology clerkships to be a critical curriculum component of effective radiology education [40]. In contrast, institutions adopting a conventional curriculum reported dominantly elective radiology clerkships. This reflects the situation in US medical schools, where radiology clerkships are rather present as an elective and are to a lesser extent a mandatory building block [21, 41] during the clinical years. Our finding that—in modern European medical curricula—students already have the possibility to be involved in radiology departments during pre-clinical years responds to the conclusions of research that promotes these practice-related activities during the early clinical curriculum phase [42]. It is clear from our research that observation tasks are present in both types of curricula. But active tasks, such as following radiological examinations, working with radiology files, as well as attending radiology conferences or participation in multidisciplinary meetings, are a more established part in modern curricula. The latter reflects the benefits of modern curricula that focus on the multidisciplinary and integrated nature of the clinical learning context.

Limitations

The limitations of this article are related to a number of issues. First, there are limitations as to our distinction between a "conventional" and ""modern" curriculum. Although we build on previous research that states that the conventional curriculum dominates in European medical curricula [12], we also have to admit that a “conventional” curricula can reflect innovative features. Due to our focus on the characteristics of the “modern” curriculum, the advantages and/or potential strengths of the traditional curriculum approach have been neglected. Also the fact that the content and structure of a curriculum is partly context bound neglects that fact that, in particular settings, a traditional approach might be more relevant and desirable.

The questionnaire was focused and as such limited to the formal nature of radiology teaching. The impact of “informal” teaching activities and, e.g., the “hidden” curriculum could therefore not be captured in this research.

A second limitation is related to the different entry requirements into medical schools. The quality of novices in the curriculum differs widely between countries and within countries, if we observe the implementation of entrance tests, the insistence on minimal grade levels, selection procedures based on interviews, etc. This type of information is still not available in our database and should be incorporated in future versions of the questionnaire. A curriculum type might be more geared to a particular type of novice.

Thirdly, we have acknowledged the possibility of response bias that is typical in survey-based studies that build on questionnaires. Although the distribution of the questionnaire was supervised by ESR and the questionnaire was filled out by radiology teaching staff and chiefs of teaching hospitals (one response per institution), questions can still be raised about the validity/reliability of certain responses. Related to this, we have to stress that the data were not obtained from a stratified sample that considered specific institutional or country characteristics. For instance, the size of the institutions was neglected in the present study. The adoption of a type of radiology curriculum can be influenced by institution size. Though we did not intend to focus on between-country variation or within country variation, the way institutions vary should be considered in future studies that adopt a sampling framework.

Future research should adopt a triangulation approach to corroborate the data gathered via the questionnaire. Qualitative interviews could help to develop a more in-depth picture.

Lastly, the statistical analysis of our research data was restricted to a descriptive exploration of curriculum characteristics. No inferential statistical tests have been carried out to test the significance of group differences due to the structure of the data set, the nature of some of the variables, and the fact that the data were not obtained from a stratified sample. Future research could look at particular patterns, associations, and potentially causal relationships between certain data.

Conclusions

Building on a distinction between modern and conventional medical curricula, this study looks at differences in the nature of formal radiology teaching. On the base of survey data from 93 European institutions, it is concluded that the adoption of modern curricula affects the way radiology is being taught: (1) there is a larger mixture of mandatory and elective courses in modern curricula; (2) there is an earlier and more continuous exposure to radiology; (3) there is no significance in the number of hours spent in teaching radiology; (4) there is a large usage of educational radiology software in modern curricula. The Internet is popular in both types of curricula; (5) a wider range of staff grades and range of professions is involved in the teaching; (6) we observe more active clerkships that build on integrated tasks.

References

Rees LH (2000) Medical education in the new millennium. J Intern Med 248(2):95–101

Breipohl WJC, Hansis M, Steiger J, Naguro T, Müller K, Mestres P (2000) Undergraduate medical education: tendencies and requirements in a rapidly developing Europe. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 42(2):5–16

Horton R (2010) A new epoch for health professionals' education. Lancet 376(9756):1875–1877. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62008-9

Christensen L (2004) The Bologna Process and medical education. Med Teach 26(7):625–629. doi:10.1080/01421590400012190

Patricio M, Den Engelsen C, Tseng D, Ten Cate O (2008) Implementation of the Bologna two-cycle system in medical education: where do we stand in 2007? Results of an AMEE-MEDINE survey. Med Teach 30(6):597–605. doi:10.1080/01421590802203512

Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA et al (2010) Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 376(9756):1923–1958. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61854-5

Harendza S, Guse AH (2009) Medical education in a bachelors and masters system. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesund 52(9):929–932. doi:10.1007/s00103-009-0923-4

Westbye H (2005) The Bologna Declaration and medical education: a policy statement from the medical students of Europe. Med Teach 27(1):83–85. doi:10.1080/01421590400019625

Teichler U (2003) Mutual recognition and credit transfer in Europe: experiences and problems. J Stud Int Educ 7:312–341

Harden RM (2006) International medical education and future directions: a global perspective. Acad Med 81(12):S22–S29

Harden RM (2002) Developments in outcome-based education. Med Teach 24(2):117–120. doi:10.1080/01421590220120669

Kourdioukova EV, Valcke M, Derese A, Verstraete KL (2011) Analysis of radiology education in undergraduate medical doctors training in Europe. Eur J Radiol 78(3):309–318. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.08.026

Gunderman RB, Siddiqui AR, Heitkamp DE, Kipfer HD (2003) The vital role of radiology in the medical school curriculum. Am J Roentgenol 180(5):1239–1242

Afaq A, McCall J (2002) Improving undergraduate education in radiology. Acad Radiol 9(2):221–223

Barzansky B, Etzel SI (2004) Educational programs in US medical schools, 2003–2004. JAMA 292(9):1025–1031

Barzansky B, Jonas HS, Etzel SI (1999) Educational programs in US medical schools, 1998–1999. JAMA 282(9):840–846

Branstetter BF, Humphrey AL, Schumann JB (2008) The long-term impact of preclinical education on medical students' opinions about radiology. Acad Radiol 15(10):1331–1339

Collins J, Dottl SL, Albanese MA (2002) Teaching radiology to medical students: an integrated approach. Acad Radiol 9(9):1046–1053

Ekelund L, Lanphear J (1997) Diagnostic radiology in an integrated curriculum: experience from the United Arab Emirates. Acad Radiol 4(9):653–656

Bui-Mansfield LT, Chew FS (2001) Radiologists as clinical tutors in a problem-based medical school curriculum. Acad Radiol 8(7):657–663

Barlev DM, Lautin EM, Amis ES, Lerner ME (1994) A survey of radiology clerkships at teaching hospitals in the United States. Investig Radiol 29(1):105–108

Samuel S, Shaffer K (2000) Profile of medical student teaching in radiology: teaching methods, staff participation, and rewards. Acad Radiol 7(10):868–874

Heflin MT, Pinheiro S, Kaminetzky CP, McNeill D (2009) 'So you want to be a clinician-educator … ': designing a clinician-educator curriculum for internal medicine residents. Med Teach 31(6):E233–E240. doi:10.1080/01421590802516772

Donovan A (2010) Radiology residents as teachers: current status of teaching skills training in United States residency programs. Acad Radiol 17(7):928–933. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2010.03.008

Morrison EH, Hollingshead J, Hubbell FA, Hitchcock MA, Rucker L, Prislin MD (2002) Reach out and teach someone: generalist residents' needs for teaching skills development. Fam Med 34(6):445–450

Erkonen WE, D'Alessandro MP, Galvin JR, Albanese MA, Michaelsen VE (1994) Longitudinal comparison of multimedia textbook instruction with a lecture in radiology education. Acad Radiol 1(3):287–292

Pusic MV, LeBlanc VR, Miller SZ (2007) Linear versus web-style layout of computer tutorials for medical student learning of radiograph interpretation. Acad Radiol 14(7):877–889. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2007.04.013

Ketelsen D, Schrodl F, Knickenberg I et al (2007) Modes of information delivery in radiologic anatomy education: impact on student performance. Acad Radiol 14(1):93–99

Grunewald M, Heckemann RA, Gebhard H, Lell M, Bautz WA (2003) COMPARE Radiology: creating an interactive Web-based training program for radiology with multimedia authoring software. Acad Radiol 10(5):543–553

Sparacia G, Cannizzaro F, D'Alessandro DM, D'Alessandro MP, Caruso G, Lagalla R (2007) Initial experiences in radiology e-learning. RadioGraphics 27(2):573–581. doi:10.1148/Rg.272065077

Wunderbaldinger P, Schima W, Turetschek K, Helbich TH, Bankier AA, Herold CJ (1999) World Wide Web and Internet: applications for radiologists. Eur Radiol 9(6):1170–1182

Davison BD, Tello R, Blickman JG (2000) World Wide Web program for optimizing and assessing medical student performance during the radiology clerkship. Acad Radiol 7(4):260–263

Grunewald M, Heckemann RA, Wagner M, Bautz WA, Greess H (2004) ELERA: a WWW application for evaluating and developing radiologic skills and knowledge. Acad Radiol 11(12):1381–1388. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2004.08.011

Jaffe CC, Lynch PJ (1995) Computer-aided instruction in radiology: opportunities for more effective learning. Am J Roentgenol 164(2):463–467

Mehta A, Dreyer KJ, Montgomery M, Wittenberg J (1999) A World Wide Web Internet engine for collaborative entry and peer review of radiologic teaching files. Am J Roentgenol 172(4):893–896

Kourdioukova EV, Valcke M, Verstraete KL (2011) The perceived long-term impact of the radiological curriculum innovation in the medical doctors training at Ghent University. Eur J Radiol 78(3):326–333. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.06.022

Relyea-Chew A, Chew FS (2007) Dedicated core clerkship in radiology for medical students development, implementation, evaluation, and comparison with distributed clerkship. Acad Radiol 14(9):1127–1136

Shaffer K, Ng JM, Hirsh DA (2009) An integrated model for radiology education: development of a year-long curriculum in imaging with focus on ambulatory and multidisciplinary medicine. Acad Radiol 16(10):1292–1301. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2009.06.002

Chew FS (2002) Distributed radiology clerkship for the core clinical year of medical school. Acad Med 77(11):1162–1163

Kourdioukova EV, Verstraete KL, Valcke M (2011) Radiological clerkships as a critical curriculum component in radiology education. Eur J Radiol 78(3):342–348. doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.08.024

Hoy RJ (1974) Radiology in medical undergraduate education. Australas Radiol 18(3):269–274

Roubidoux MA, Packer MM, Applegate KE, Aben G (2009) Female medical students' interest in radiology careers. J Am Coll Radiol 6(4):246–253

Acknowledgements

This article was kindly prepared by Elena Oris, Koenraad Verstraete (Department of Radiology, Ghent University Hospital) and Martin Valcke (Department of Educational, Ghent University) on behalf of the Working Group on Undergraduate Education (Chairperson: Stephen J. Golding; Chairperson Education Committee; Éamann Breatnach; Members: Dermot Malone, Zita Morvay, Salvador Pedraza, Endre Szabó, Koenraad Verstraete, Jesus Dámaso Aquerreta Beola) of the ESR Education Committee.

It was approved by the ESR Executive Council as an official ESR document in February 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1. List of countries in the “ESR survey on undergraduate teaching 2010”

AT | Austria (C, M) |

BE | Belgium (C,M) |

BG | Bulgaria (C) |

CH | Switzerland (M) |

CZ | Czech Republic (C,M) |

DE | Germany (C,M) |

EE | Estonia (C) |

ES | Spain (C,M) |

FI | Finland (C,M) |

FR | France (C,M) |

GR | Greece (C) |

HR | Croatia (C,M) |

HU | Hungary (C) |

IE | Ireland (M) |

IT | Italy (C,M) |

LT | Lithuania (C) |

LV | Latvia (C) |

ME | Montenegro (C) |

NL | The Netherlands (M) |

NO | Norway (C) |

PL | Poland (C,M) |

PT | Portugal (C) |

RO | Romania (C) |

SE | Sweden (M) |

SI | Slovenia (C) |

TR | Turkey (M) |

UK | United Kingdom (M) |

C = Conventional curriculum; M = Modern curriculum

Appendix 2. Questionnaire on undergraduate radiology teaching (ESR Education Committee) 2010

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Oris, E., Verstraete, K., Valcke, M. et al. Results of a survey by the European Society of Radiology (ESR): undergraduate radiology education in Europe—influences of a modern teaching approach. Insights Imaging 3, 121–130 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-012-0149-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-012-0149-0