ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

In our ever-increasingly multicultural, multilingual society, medical interpreters serve an important role in the provision of care. Though it is known that using untrained interpreters leads to decreased quality of care for limited English proficiency patients, because of a short supply of professionals and a lack of formalized, feasible education programs for volunteers, community health centers and internal medicine practices continue to rely on untrained interpreters.

OBJECTIVE

To develop and formally evaluate a novel medical interpreter education program that encompasses major tenets of interpretation, tailored to the needs of volunteer medical interpreters.

DESIGN

One-armed, quasi-experimental retro-pre–post study using survey ratings and feedback correlated by assessment scores to determine educational intervention effects.

PARTICIPANTS

Thirty-eight students; 24 Spanish, nine Mandarin, and five Vietnamese. The majority had prior interpreting experience but no formal medical interpreter training.

OUTCOME MEASURES

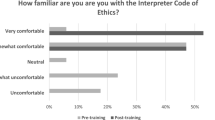

Students completed retrospective pre-test and post-test surveys measuring confidence in and perceived knowledge of key skills of interpretation. Primary outcome measures were a 10-point Likert scale for survey questions of knowledge, skills, and confidence, written and oral assessments of interpreter skills, and qualitative evidence of newfound knowledge in written reflections.

RESULTS

Analyses showed a statistically significant (P <0.001) change of about two points in mean self-ratings on knowledge, skills, and confidence, with large effect sizes (d > 0.8). The second half of the program was also quantitatively and qualitatively shown to be a vital learning experience, resulting in 18 % more students passing the oral assessments; a 19 % increase in mean scores for written assessments; and a newfound understanding of interpreter roles and ways to navigate them.

CONCLUSIONS

This innovative program was successful in increasing volunteer interpreters’ skills and knowledge of interpretation, as well as confidence in own abilities. Additionally, the program effectively taught how to navigate the roles of the interpreter to maintain clear communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002.

Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: a comparison of professional versus ad hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;20(10):1–8.

Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS, Meltzer D, Shorey JM, Levinson W, Thisted RA. Impact of interpreter services on delivery of health care to limited–english-proficient patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):468–474.

National Council on Interpreting in Health Care. National standards for healthcare interpreter training programs. 2011. Available at: http://www.ncihc.org/assets/documents/National_Standards_5-09-11.pdf. Accessibility verified May 1,2013.

Hwa-Froelich DA, Westby CE. Considerations when working with interpreters. Commun Disord Q. 2003;24(2):78–85.

Casey M. Providing health care to latino immigrants: community-based efforts in the rural midwest. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1709–1711.

Vandervort E. Linguistic services in ambulatory clinics. J Transcult Nurs. 2003;14(4):358–366.

“Volunteer Health Interpreters Organization.” Volunteer Health Interpreters Organization. Volunteer Health Interpreters Organization at UC Berkeley, n.d. Web. Available at: http://calhbc.wordpress.com/decal-class/. Accessibility verified May 1, 2013.

Lacorte M, Canabal E. Interaction with heritage language learners in foreign language classrooms. In: Blyth C, ed. The Sociolinguistics of Foreign-Language Classrooms: Contributions of the Native, the near Native, and the Non-Native Speaker. Boston: Heinle and Heinle; 2002:107–129.

Larrison CR, Velez-Ortiz D, Hernandez PM, Piedra LM, Goldberg A. Brokering language and culture: can ad hoc interpreters fill the language service gap at community health centers? Soc Work Public Health. 2010;25(3):387–407.

Long R, Roy NG, eds. Bridging the Gap: An Interactive Textbook for Medical Interpreters. 1st ed. Seattle: Cross Cultural Health Care Program; 2002.

Butow PN, Lobb E, Jefford M, Goldstein D, Eisenbruch M. A bridge between cultures: interpreters' perspectives of consultations with migrant oncology patients. Support Care Canc. 2012;20(2):235–244.

Langdon HW, Cheng L-RL. Collaborating with interpreters and translators: A guide for communication disorders professionals. Thinking Publications, 2002.

Smirnov S. An overview of liaison interpreting. Perspect Stud Transl. 1997;5(2):211–226.

Cross Cultural Healthcare Program. Bridging the Gap Training Programs. The Cross Cultural Healthcare Program. July 25, 2012. Available at http://xculture.org/medical-interpreter-training/bridging-the-gap-training-program. Accessibility verified May 1, 2013.

Howard G. Internal invalidity in pretest–posttest self-report evaluations and a re-evaluation of retrospective pretests. Appl Psychol Meas. 1979;3(1):1–23.

Hill L. Revisiting the retrospective pretest. Am J Eval. 2005;26(4):501–517.

Fan X. Statistical significance and effect size in education research: two sides of a coin. J Educ Res. 2001;94(5):275–282.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988.

McCartney K, Rosenthal R. Effect size, practical importance, and social policy for children. Child Dev. 2003;71(1):173–180.

Cohen J. Things I have learned (so far). Am Psychol. 1990;45(12):1304.

Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ. Errors in pediatric medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in encounters. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):6–14.

Jacobs E. The impact of an enhanced interpreter service intervention on hospital costs and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;22(2):306–311.

Baker D, Parker R, Williams M, Coates WPK. Use and effectiveness of interpreters in an emergency department. JAMA. 1996;275(10):783–788.

Falk GA, Robb WB, Khan WH, Hill AD. Student-selected components in surgery: providing practical experience and increasing student confidence. Ir J Med Sci. 2009;178:267–272.

Acknowledgements

Contributors

We gratefully acknowledge Johanna Parker, MA, Margarita Bekker, AHI (CCHI), BA, and Natalia Becerra, MA, the instructors of the program, for sharing their passion for the medical interpreter profession and vast experience with our students through their enthusiastic instruction and mentoring. We are also deeply grateful to Stanford Interpreter Services for their mentorship and tireless support of the program. We also thank Jie Li, PhD, of the Center of Excellence for Diversity in Medical Education of Stanford School of Medicine, for her valuable input in survey review and editing, as well as advice on program evaluation strategies. We further extend our gratitude to Sylvia Bereknyei, DrPH, MS for her generous advice and assistance in editing and review of the manuscript. Finally, we thank Raymond Balise, PhD, of the Center for Health Research and Policy of Stanford School of Medicine, for his help with statistical analysis and advice on data presentation.

Funders

The costs of instruction of the Bridging the Gap curriculum and program costs of instructor and coach time were generously donated to the Cardinal Free Clinics by Stanford Hospital Guest Services and Stanford Interpreter Services (SIS). The study itself did not receive financial support from any individual or organization.

Prior Presentations

2012 WGEA/WGSA/WOSR/WAAHP AAMC Western Regional Conference, April 1, 2012. The 11th Annual Community Health Symposium, Stanford School of Medicine, Office of Community Health, November 8, 2012. The Society of Student-Run Free Clinics (SSRFC) 2013 Conference, January 26, 2013.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 131 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hasbún Avalos, O., Pennington, K. & Osterberg, L. Revolutionizing Volunteer Interpreter Services: An Evaluation of an Innovative Medical Interpreter Education Program. J GEN INTERN MED 28, 1589–1595 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2502-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2502-5