Abstract

BACKGROUND

Shared decision-making, in which physicians and patients openly explore beliefs, exchange information, and reach explicit closure, may represent optimal physician–patient communication. There are currently no universally accepted methods to assess medical students’ competence in shared decision-making.

OBJECTIVE

To characterize medical students’ shared decision-making with standardized patients (SPs) and determine if students’ use of shared decision-making correlates with SP ratings of their communication.

DESIGN

Retrospective study of medical students’ performance with four SPs.

PARTICIPANTS

Sixty fourth-year medical students.

MEASUREMENTS

Objective blinded coding of shared decision-making quantified as decision moments (exploration/articulation of perspective, information sharing, explicit closure for a particular decision); SP scoring of communication skills using a validated checklist.

RESULTS

Of 779 decision moments generated in 240 encounters, 312 (40%) met criteria for shared decision-making. All students engaged in shared decision-making in at least two of the four cases, although in two cases 5% and 12% of students engaged in no shared decision-making. The most commonly discussed decision moment topics were medications (n = 98, 31%), follow-up visits (71, 23%), and diagnostic testing (44, 14%). Correlations between the number of decision moments in a case and students’ communication scores were low (rho = 0.07 to 0.37).

CONCLUSIONS

Although all students engaged in some shared decision-making, particularly regarding medical interventions, there was no correlation between shared decision-making and overall communication competence rated by the SPs. These findings suggest that SP ratings of students’ communication skill cannot be used to infer students’ use of shared decision-making. Tools to determine students’ skill in shared decision-making are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

BACKGROUND

Medical students must achieve communication skills competence to provide effective care to patients. Communication skills have been linked to patient outcomes such as satisfaction and adherence1,2. Doctor–patient communication can entail many behaviors including establishing rapport, eliciting the patient’s perspective, and engaging in shared decision-making.

Shared decision-making has been promoted by experts in clinical communication as an ideal model of physician–patient communication. Shared decision-making is based on the premise that the best medical decision for an individual patient incorporates the patient’s preferences and values through a process in which the physician and patient openly explore beliefs, exchange information, and reach explicit closure.3–8 Advocates of shared decision-making believe it provides a better medical encounter experience than either paternalistic (physician-directed) or consumerist (patient-directed) decision-making styles.7,9 Patients who experience their preferred decision-making style with their primary physicians are more likely to perceive those physicians as providing excellent care.10,11 Some studies show that shared decision-making improves patient satisfaction, adherence to medications, and health outcomes. 12–14

Assessing shared decision-making behavior may not be simple, for either practicing physicians or students. It has been operationalized as a set of measurable communication behaviors incorporating patients’ preferences and values.4,7,15 There are three domains of behaviors common to the shared decision-making process: 1) exchange of feelings and beliefs; 2) exchange of information about the disease, its diagnosis and treatment; and 3) reaching closure.4,7,15 In a qualitative study examining the relationship of shared decision-making to patient satisfaction, the presence or absence of shared decision-making in a given encounter did not consistently correlate with patients’ satisfaction with their physicians’ communication and relationship-building behavior, suggesting that shared decision-making is only one of several facets of communication that influence overall patient satisfaction.15

Medical students’ competence in communication skills is often assessed through the communication component of clinical practice examinations in which trained standardized patients typically assess students’ communication competence using a communication behaviors checklist.16 These ratings may or may not capture medical students’ use of shared decision-making. For instance, communication behaviors such as building rapport, expressing empathy, and using body language may occur in the absence (or presence) of active patient involvement in decision-making.17 Nonetheless, there is a growing need to assess medical student engagement in shared decision-making behavior with their patients to understand how trainees develop this skill.18 Physician belief in the benefits of shared decision-making and motivation to engage in shared decision-making are crucial facilitators of this behavior19, and it is important to impart these attitudes during the formative stages of training before practice patterns are established.20 However, with their less mature clinical skills, students may be more challenged than physicians by the time constraints of ambulatory encounters, which are a major barrier to shared decision-making.21 We designed this study to characterize the nature and amount of medical students’ shared decision-making and to determine if ratings of general communication correlate with students’ use of shared decision-making.

METHODS

Design

This was a retrospective observational study of medical students’ performance with standardized patients. The Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Subjects and Setting

After the third-year core clerkships, all University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) students are required to take the Clinical Performance Examination (CPX). The CPX is an eight-station comprehensive standardized patient examination developed by the eight medical schools comprising the California Consortium for the Assessment of Clinical Competence. Each CPX encounter lasts 15 minutes and is videotaped. After each encounter, standardized patients complete a criterion-based checklist evaluating students’ history taking, physical examination, communication and information sharing skills. Checklist accuracy by the consortium’s standardized patients exceeds 95%.22

A total of 143 UCSF medical students comprising the class of 2006 participated in the May–June 2005 CPX. The class of 2006 was 63% female. The self-described racial makeup of the class was 48% White, 33% Asian, 3% Black, 2% Native American, 6% other race, 2% unknown, and 6% multirace. We used a random number generator to select a 60-student probability sample for the study. This sample size (n = 60) gave adequate (80%) power to detect correlations of 0.35 and outstanding power (99%) to detect correlations of 0.5 or larger. All CPX encounters were video-recorded as part of usual exam procedure. Videotapes of the four study cases from the 60 randomly selected students were transcribed for analysis.

Communications skills cases and rating instrument: For this study, we selected four CPX cases that highlighted medical conditions likely to prompt decision-making opportunities regarding disease management or behaviors. (Appendix 1, available online) For shared decision-making to occur, one necessary prerequisite is a decision with multiple options4,23. Standardized patients participated in 17 hours of training over five sessions. Two different standardized patients portrayed the hypertension case and three portrayed each of the other three cases. The trainer assessed the standardized patients for consistency of portrayal and checklist accuracy during training and the exam.

The CPX case checklists used by the standardized patients included seven communication items (listening, rapport building, professional demeanor, and addressing the patient’s perspective and needs) based on the Common Ground checklist. This checklist was previously shown to have high reliability (rho = > 0.80) when completed by trained raters and high correlation with global ratings of communication by faculty experts (r = 0.84).24 Standardized patients scored the communication items from 0 to 1.0 on a six-point scale (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, as defined in Appendix 2, available online), with total scores reported as percentages (maximum 100%).

Shared decision-making coding: Four investigators (KEH, AF, AT, GS) coded shared decision-making using a coding manual (Appendix 3, summary available online) and coding worksheet (Appendix 4, available online) from an instrument used to code physician–patient encounters.15 The worksheet includes checkboxes for decision moment identification and each of the key dimensions of shared decision-making within a single decision moment: exploration/articulation of perspective (beliefs, values), information sharing, and explicit closure, each of which could be done by the student, standardized patient, or both. In contrast to some other published shared decision-making scales,6,11,17 we captured both the student physician’s sharing of beliefs and values and the students’ responses to information from the patient. A single worksheet was used for each decision moment, which begins when a suggestion is made to change behavior or consider medical therapy or testing. Each dimension was marked as present or absent for each decision discussed by the student and standardized patient; each dimension was attributed to the student or patient only once per decision moment.

Examples of shared decision-making decision moment discussions between students and standardized patients are shown in Text box 1. There was no maximum number of decision moments per case; it was also possible for an encounter to have none. Each of the 240 encounters was coded by two coders, and reconciled by consensus discussion between the two coders, or with other coders in the event of discrepancy, which was rare.

Text box 1: Shared decision-making decision moment examples.

Analysis

For analysis, we defined shared decision-making as a decision moment that included at least four of the possible ten decision-making elements (in addition to decision identification) on the worksheet (Appendix 4, available online) in which one of the four was closure of the decision by the patient. Inclusion of at least four elements ensures participation by both student and patient with presence of essential domains of shared decision-making (exchange of feelings and beliefs, exchange of information, and closure). This cutoff is similar to that used in prior literature, with a slightly lower cutoff due to students’ earlier point in training than practicing physicians.15 Closure of the decision by the patient is essential to determine whether shared decision-making has occurred; without closure by the patient, the physician may make decisions unilaterally. Traditionally, physicians are more vocal about closure than patients (e.g., ‘we will change your medicine’; ‘I want you to monitor your glucose’); patients’ verbalization of closure ensures their agreement.

We calculated the total number of decision moments overall and by decision topic. The key outcome used in correlation analyses was the number of decision moments with ≥4 elements as defined above. We used Spearman rank correlations, a non-parametric test, to examine the association between number of decision moments with ≥4 elements and the CPX communication score for each case. Data analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago).

RESULTS

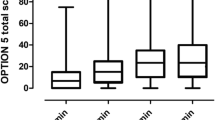

The 240 encounters from the 60 students generated 779 decision moments across all four cases. Of the 779 decision moments, 483 (62%) had shared decision-making scores of four or greater, 390 (50%) included patient closure, and 312 (40%) had both. These 312 comprised the shared decision moment dataset. The number of decision moments per student across all four cases ranged from 6.00 to 23.00; the mean (standard deviation) was 13.98 (3.07). Considering each case individually, the number of decision moments was: diabetes 3.93 (2.25), headache 2.15 (1.13), hypertension 3.87 (1.23), and teen 2.97 (1.22).

All students engaged at least once in shared decision-making (i.e., included at least four elements, one of which was patient closure) in both the hypertension and teen cases. In contrast, for the other two cases, 5% (diabetes) and 12% (headache) of students did not engage in any shared decision-making.

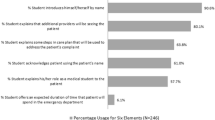

As shown in Table 1, among the 312 shared decision moments, the most commonly discussed topics were medications (n = 98, 31%), follow-up visits (71, 23%), and diagnostic testing (44, 14%). Lifestyle changes such as exercise (30, 9%) and diet (27, 10%) were discussed less frequently using shared decision-making.

Association Between Communication Scores and Shared Decision Making

The mean (standard deviation) communication scores out of a maximum of 100 for the 60 students were: diabetes 68.71 (7.86), headache 69.57 (7.99), hypertension 61.23 (6.81), and teen 69.19 (8.79). The correlations between number of shared decision-making moments in a case and the respective communication score from the standardized patient were low for three cases: diabetes (rho = 0.07; 95% confidence interval -0.109, 0.32), headache (rho = 0.10; -0.16, 0.34), and teen (rho = 0.08; -0.18, 0.33), and moderate for the hypertension case (rho = 0.37; 0.13, 0.57).

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of student-standardized patient encounters in a high-stakes clinical skills examination, we found that, although all students engaged in some shared decision-making with their patients, the number of shared decision-making moments per case had limited correlation with the checklist communication score rendered by standardized patients. This finding implies shortcomings in existing measures of communication skills in that shared decision-making is independent of other aspects of communication, such as students’ communication behaviors and patients’ perceptions of rapport. Shared decision-making seems to involve additional aspects of the interaction and may challenge students working with standardized (or actual) patients to collaborate in care planning in ways not rewarded in typical communication checklists.

CPX scores may reflect meaningful aspects of communication that differ from shared decision-making. Although shared decision-making is often cited as an ideal model of physician–patient communication, our findings of limited correlation between shared decision-making and overall communication scores from standardized patients are consistent with prior literature showing that patients’ preferences for decision-making style are complex and variable. Approximately one third of patients may prefer a different style,10,15,25 particularly based on their medical conditions.26 Other aspects of communication, such as empathy and rapport, may be valued more highly than decision-making style.

Our results suggest that commonly used standardized patient checklists could be modified to include explicit assessment of shared decision-making behaviors. Our work extends that done using the OPTION scale6, another scale for assessing shared decision-making, in student-standardized patient encounters, in which capturing balanced measures of both persons’ contributions is important in student assessment. Assessing students’ shared decision-making in standardized patient examinations raises practical challenges including requirements for detailed coding of interactions and extensive standardized patient training. While this task is daunting, the evidence for shared decision-making as a preferred communication strategy is growing and the applications expanding.27–31 To address feasibility concerns, efforts could focus on a few key components of shared decision-making while still capturing both patient and physician perspectives on decision-making.32,33 Alternatively, assessing shared decision-making in formative standardized patient examinations might allow for meaningful feedback from patients to students34 without necessitating high checklist reliability.

It is encouraging that, in our study, all students engaged in some shared decision-making. Of the decision moments, almost half met our criteria for shared decision-making. This percentage is comparable to findings with actual physician–patient encounters, in which, using a slightly different threshold, half of decision moments qualified as shared decision-making.15 Our results also provide insights into students’ predilection to emphasize biomedical rather than lifestyle topics while counseling patients with a variety of clinical presentations. We found that students used shared decision-making more when discussing medical interventions, such as medications and tests, rather than patient self-management strategies. Prior studies have shown low rates of physician counseling about lifestyle modification.35,36 Students may lack knowledge about the benefits of lifestyle modification, or, more likely, about how to engage patients to implement these changes.37 These findings suggest that medical school curricula and assessments should increase their focus on lifestyle modification; students should possess the skills to empower their patients accordingly.

This study has limitations. We collected data from a single institution in a single year. Although we compared scores for shared decision-making to standardized patient communication ratings, we do not know if either score would translate to improved patient outcomes with actual patients. These findings apply only to the particular communication skills checklist we used, which may not generalize to other communication skills assessments. Other shared decision-making scales might have yielded different results, although our scale does address eight of nine essential elements of shared decision-making identified in a systematic review.38 Other more lengthy shared decision-making scales could be even less practical for medical school assessments.6,11 Further study of our shared decision-making scale could provide information about its psychometric properties. Strengths of our study include the large number of encounters assessed, the detailed, rigorous measurement of shared decision-making behaviors, and the inclusion of a range of acute and chronic patient presentations.

In this study of medical students’ shared decision-making with standardized patients, we found minimal correlation between the frequency of shared decision-making and standardized patients’ ratings of overall communication. All students engaged in some shared decision-making, although they focused their discussions on physician-oriented topics rather than patient self-management. Further study is needed to determine how medical students can best engage their patients in collaborative care, and how educators can measure that engagement with psychometrically sound instruments. That knowledge would enhance both medical education and patient care.

References

Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician–patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553–559.

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P. Shared decision-making in primary care: the neglected second half of the consultation. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49(443):477–482.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Kinnersley P, Grol R. Shared decision making and the concept of equipoise: the competences of involving patients in healthcare choices. Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50(460):892–899.

Gwyn R, Elwyn G. When is a shared decision not (quite) a shared decision? Negotiating preferences in a general practice encounter. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(4):437–447.

Elwyn G, Edwards A, Wensing M, Hood K, Atwell C, Grol R. Shared decision making: developing the OPTION scale for measuring patient involvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(2):93–99.

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681–692.

Charles CA, Whelan T, Gafni A, Willan A, Farrell S. Shared treatment decision making: what does it mean to physicians? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(5):932–936.

Roter D. The enduring and evolving nature of the patient-physician relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39(1):5–15.

Murray E, Pollack L, White M, Lo B. Clinical decision-making: Patients' preferences and experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(2):189–196.

Braddock CH 3rd, Fihn SD, Levinson W, Jonsen AR, Pearlman RA. How doctors and patients discuss routine clinical decisions. Informed decision making in the outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12(6):339–345.

Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, Knowles SB, Lavori PW, Lapidus J, Vollmer WM, Better Outcomes of Asthma Treatment (BOAT) Study Group. Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(6):566–577.

Urowitz S, Deber R. How consumerist do people want to be? Preferred role in decision-making of individuals with HIV/AIDS. Healthc Policy. 2008;3(3):e168–e182.

White DB, Braddock CH 3rd, Bereknyei S, Curtis JR. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):461–467.

Saba GW, Wong ST, Schillinger D, et al. Shared decision-making and the experience of partnership in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(1):54–62.

Hauer KE, Hodgson CS, Kerr KM, Teherani A, Irby DM. A national study of medical student clinical skills assessment. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S25–S29.

Guimond P, Bunn H, O'Connor AM, Jacobsen MJ, Tait VK, Drake ER, Graham ID, Stacey D, Elmslie T. Validation of a tool to assess health practitioners' decision support and communication skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50(3):235–245.

Godolphin W. Shared decision-making. Healthc Q. 2009;12 Spec No Patient:e186-90.

Gravel K, Légaré F, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:16.

Towle A, Godolphin W, Grams G, Lamarre A. Putting informed and shared decision making into practice. Health Expect. 2006;9(4):321–332.

Légaré F, Ratté S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):526–535.

Heine N, Garman K, Wallace P, Bartos R, Richards A. An analysis of standardized patient checklist errors and their effect on student scores. Med Educ. 2003;37(2):99–104.

Whitney SN, Holmes-Rovner M, Brody H, Schneider C, McCullough LB, Volk RJ, McGuire AL. Beyond shared decision making: an expanded typology of medical decisions. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(5):699–705.

Lang F, McCord R, Harvill L, Anderson DS. Communication assessment using the common ground instrument: psychometric properties. Fam Med. 2004;36(3):189–198.

Swenson SL, Zettler P, Lo B. 'She gave it her best shot right away': patient experiences of biomedical and patient-centered communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61(2):200–211.

Winefield HR, Murrell TG, Clifford JV, Farmer EA. The usefulness of distinguishing different types of general practice consultation, or are needed skills always the same? Fam Pract. 1995;12(4):402–407.

Murphy J, Chang H, Montgomery JE, Rogers WH, Safran DG. The quality of physician–patient relationships. Patients' experiences 1996-1999. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(2):123–129.

Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE Jr. Expanding patient involvement in care. Effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102(4):520–528.

Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE Jr, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):448–457.

Xu KT, Borders TF, Arif AA. Ethnic differences in parents' perception of participatory decision-making style of their children's physicians. Med Care. 2004;42(4):328–335.

van der Weijden T, Legare F, Boivin A, Burgers JS, van Veenandaal H, Stiggelbout AM, Faber M, Elwyn G. How to integrate individual patient values and preferences in clinical practice guidelines? A research report. Implement Sci. 2010;5:10.

Melbourne E, Sinclair K, Durand MA, Légaré F, Elwyn G. Developing a dyadic OPTION scale to measure perceptions of shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):177–183.

Goossensen A, Zijlstra P, Koopmanschap M. Measuring shared decision making processes in psychiatry: skills versus patient satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(1–2):50–56.

Pfeiffer CA, Kosowicz LY, Holmboe E, Want Y. Face-to-face clinical skills feedback: lessons from the analysis of standardized patients’ work. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17:254–256.

Spencer EH, Frank E, Elon LK, Hertzberg VS, Serdula MK, Galuska DA. Predictors of nutrition counseling behaviors and attitudes in US medical students. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(3):655–662.

Frank E, Tong E, Lobelo F, Carrera J, Duperly J. Physical activity levels and counseling practices of U.S. medical students. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(3):413–421.

Parker WA, Steyn NP, Levitt NS, Lombard CJ. They think they know but do they? Misalignment of perceptions of lifestyle modification knowledge among health professionals. Public Health Nutr. 2010;28:1–10 [Epub ahead of print].

Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–312.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kathleen Kerr and Suzy Hull for their assistance with shared decision-making coding, Joanne Batt for data management, and Steven Gregorich and Patricia S. O’Sullivan for expert advice.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by Stemmler Medical Education Research Fund of the National Board of Medical Examiners. Dr. Fernandez was also partly supported by the Arnold P. Gold Foundation Professorship award.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

Description of four standardized patient cases used in the evaluation of shared decision-making. (DOC 26 kb)

ESM 2

PATIENT/PHYSICIAN INTERACTION Communication rating form used by standardized patients. (DOC 37 kb)

ESM 3

Additional study methods related to shared decision-making coding. (DOC 23.5 kb)

ESM 4

Shared decision-making coding worksheet. (DOC 44.5 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hauer, K.E., Fernandez, A., Teherani, A. et al. Assessment of Medical Students’ Shared Decision-Making in Standardized Patient Encounters. J GEN INTERN MED 26, 367–372 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1567-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1567-7