Abstract

The psychological bases of ideology have received renewed attention amid growing political polarization. Nevertheless, little research has examined how one’s understanding of political ideas might moderate the relationship between “pre-political” psychological variables and ideology. In this paper, we fill this gap by exploring how expertise influences citizens’ ability to select ideological orientations that match their psychologically rooted worldviews. We find that expertise strengthens the relationship between two basic social worldviews—competitive-jungle beliefs and dangerous-world beliefs and left–right self-placement. Moreover, expertise strengthens these relationships by boosting the impact of the worldviews on two intervening ideological attitude systems—social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. These results go beyond previous work on expertise and ideology, suggesting that expertise strengthens not only relationships between explicitly political attitudes but also the relationship between political attitudes and their psychological antecedents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In the competitive-jungle/SDO analysis, the predictors in the final equation containing SDO accounted for a significant proportion of variance in left–right self-placement, F(5, 279) = 13.59, p < .001, with adjusted R 2 = .173.

All bootstrap analyses used 5000 replications to estimate indirect effects.

In the dangerous-world/RWA analysis, the predictors in the final equation containing RWA accounted for a significant proportion of variance in left–right self-placement, F(5, 279) = 32.65, p < .001, with adjusted R 2 = .305.

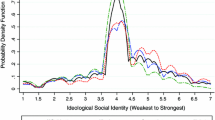

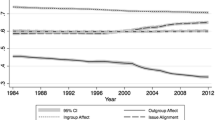

Duckitt and Sibley (2009) have argued that the competitive-jungle/SDO path should have its strongest effects on economic issues, while the dangerous-world/RWA path should have its strongest effects on social issues. Given the high correlation between our economic and social ideology indicators (r = .58, p < .001), we use a composite of the two. However, when the competitive-jungle/SDO analyses in Table 2, Model 2 of Table 4, and Fig. 1 are replicated using the economic ideology item as the sole dependent measure, all results remain the same. Similarly, when the dangerous-world/RWA analyses in Table 3, Model 3 of Table 4, and Fig. 2 are replicated using the social ideology item only as the dependent measure, the results also remain the same.

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: Harper.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Altemeyer, B. (1998). The other “authoritarian personality”. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 30, 47–92.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. G. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social-psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bennett, S. (2006). Democratic competence, before converse and after. Critical Review, 18, 105–142.

Brewer, P. R., & Steenbergen, M. R. (2002). All against all: How beliefs about human nature shape foreign policy opinions. Political Psychology, 23, 39–58.

Campbell, A., Converse, P., Miller, W., & Stokes, W. (1960). The American voter. New York: Wiley.

Christie, R. (1954). Authoritarianism re-examined. In R. Christie & M. Jahoda (Eds.), Studies in the scope and method of “The Authoritarian Personality” (pp. 123–196). Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Converse, P. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and discontent. New York: Free Press.

Converse, P. (2000). Assessing the capacity of mass electorates. Annual Review of Political Science, 3, 331–353.

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Duckitt, J. (2001). A dual process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 22, 41–113.

Duckitt, J., & Fisher, K. (2003). The impact of social threat on worldview and ideological attitudes. Political Psychology., 24, 199–222.

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2009). A dual process model of ideological attitudes and system justification. In J. T. Jost, A. C. Kay, & H. Thorisdottir (Eds.), Social and psychological bases of ideology and system justification (pp. 292–313). New York: Oxford University Press.

Duckitt, J., Wagner, C., du Plessis, I., & Birum, I. (2002). The psychological bases of ideology and prejudice: Testing a dual-process model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 75–93.

Duriez, B., & Soenens, B. (2006). Personality, identity styles and authoritarianism: An integrative study among late adolescents. European Journal of Personality, 20, 397–417.

Duriez, B., Van Hiel, A., & Kossowska, M. (2005). Authoritarianism and social dominance in Western and Eastern Europe: The importance of the socio-political context and of political interest and involvement. Political Psychology, 26, 299–320.

Erikson, R. S., & Tedin, K. L. (2003). American public opinion (6th ed.). New York: Longman.

Eysenck, H. J. (1954). The psychology of politics. New York: Praeger.

Federico, C. M. (2007). Expertise, evaluative motivation, and the structure of citizens’ ideological commitments. Political Psychology, 28, 535–562.

Federico, C. M., & Goren, P. (2009). Motivated social cognition and ideology: Is attention to elite discourse a prerequisite for epistemically motivated political affinities? In J. T. Jost, A. C. Kay, & H. Thorisdottir (Eds.), Social and psychological bases of ideology and system justification (pp. 267–291). New York: Oxford University Press.

Federico, C. M., & Schneider, M. (2007). Political expertise and the use of ideology: Moderating effects of evaluative motivation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 71, 221–252.

Feldman, S. (2003). Values, ideology, and structure of political attitudes. In D. O. Sears, L. Huddy, & R. Jervis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 477–508). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fiske, S. T., Lau, R. R., & Smith, R. A. (1990). On the varieties and utilities of political expertise. Social Cognition, 8, 31–48.

Goren, P. (2004). Political sophistication and policy reasoning: A reconsideration. American Journal of Political Science, 48, 462–478.

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20, 98–116.

Hinich, M. J., & Munger, M. C. (1994). Ideology and the theory of political choice. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Hunter, J. D. (1991). Culture wars: The struggle to define America. New York: Basic Books.

Jost, J. T. (2006). The end of the end of ideology. American Psychologist, 61, 651–670.

Jost, J. T., Federico, C. M., & Napier, J. (2009). Political ideology: Its structure, function, andelective affinities. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 307–337.

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375.

Jost, J. T., Napier, J. L., Thorisdottir, H., Gosling, S. D., Palfai, T. P., & Ostafin, B. (2007). Are needs to manage uncertainty and threat associated with political conservatism or ideological extremity? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 989–1007.

Jost, J. T., Nosek, B. A., & Gosling, S. D. (2008). Ideology: Its resurgence in social, personality, and political psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 126–136.

Judd, C. M., & Krosnick, J. A. (1989). The structural bases of consistency among political attitudes: Effects of expertise and attitude importance. In A. R. Pratkanis, S. J. Breckler, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Attitude structure and function (pp. 99–128). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kemmelmeier, M. (2007). Political conservatism, rigidity, and dogmatism in American foreign policy officials: The 1966 Mennis data. The Journal of Psychology, 141, 77–90.

Kinder, D. R. (2006). Belief systems today. Critical Review, 18, 197–216.

Kinder, D. R., & Sears, D. O. (1985). Public opinion and political action. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (3rd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 659–741). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Kruglanski, A. W. (1996). Motivated social cognition: Principles of the interface. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: A handbook of basic principles (pp. 493–522). New York: Guilford Press.

Lakoff, G. (1996). Moral politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lane, R. E. (1962). Political ideology. New York: Free Press.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. (2006). How voters decide: Information processing in election campaigns. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lavine, H., Thomsen, C. J., & Gonzales, M. H. (1997). The development of interattitudinal consistency: The shared consequences model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 735–749.

Layman, G. C., & Carsey, T. M. (2002). Party polarization and “conflict extension” in the American electorate. American Journal of Political Science, 46, 786–802.

Lipset, S. M. (1960). Political man. New York: Doubleday.

Long, J. S., & Ervin, L. H. (2000). Using heteroscedasticity consistent standard errors in the linear regression model. American Statistician, 54, 217–234.

Luskin, R. (1987). Measuring political sophistication. American Journal of Political Science, 31, 856–899.

Marcus, G. E. (2002). The sentimental citizen: Emotion in democratic politics. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Marcus, G. E. (2008). Blinded by the light: Aspiration and inspiration in political psychology. Political Psychology, 29, 313–330.

McFarland, S. (2005). On the eve of war: Authoritarianism, social dominance, and American students’ attitudes toward attacking Iraq. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 360–367.

Popkin, S. L. (1991). The reasoning voter. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Redlawsk, D. P. (2006). Feeling politics: Emotion in political information processing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rokeach, M. (1960). The open and closed mind. New York: Basic Books.

Sapiro, V. (2004). Not your parents’ political socialization. Annual Review of Political Science, 7, 1–23.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental designs: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.

Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M. S., & Duckitt, J. (2007). Effects of dangerous and competitive worldviews on right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation over a five-month period. Political Psychology, 28, 357–371.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sniderman, P. M., Brody, R. A., & Tetlock, P. E. (1991). Reasoning and choice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sniderman, P. M., & Bullock, J. (2004). A consistency theory of public opinion and political choice: The hypothesis of menu dependence. In W. E. Saris & P. M. Sniderman (Eds.), Studies in public opinion: Attitudes, nonattitudes, measurement error, and change (pp. 337–357). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Stangor, C., & Leary, S. P. (2006). Intergroup beliefs: Investigations from the social side. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 243–281.

Stenner, K. (2005). The authoritarian dynamic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stimson, J. A. (2004). Tides of consent. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Weber, C. W., & Federico, C. M. (2007). Interpersonal attachment and patterns of ideological belief. Political Psychology, 28, 389–416.

Wegener, D. T., & Fabrigar, L. R. (2000). Analysis and design for non-experimental data: Addressing causal and non-causal hypotheses. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 412–450). New York: Cambridge.

Wilson, G. D. (1973). The psychology of conservatism. New York: Academic Press.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Federico, C.M., Hunt, C.V. & Ergun, D. Political Expertise, Social Worldviews, and Ideology: Translating “Competitive Jungles” and “Dangerous Worlds” into Ideological Reality. Soc Just Res 22, 259–279 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-009-0097-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-009-0097-0