Abstract

This paper studies multidimensional poverty for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, El Salvador, Mexico and Uruguay for the period 1992–2006. The approach overcomes the limitations of the two traditional methods of poverty analysis in Latin America (income-based and unmet basic needs) by combining income with five other dimensions: school attendance for children, education of the household head, sanitation, water and shelter. The results allow a fuller understanding of the evolution of poverty in the selected countries. Over the study period, El Salvador, Brazil, Mexico and Chile experienced significant reductions in multidimensional poverty. In contrast, in urban Uruguay there was a small reduction in multidimensional poverty, while in urban Argentina the estimates did not change significantly. El Salvador, Brazil and Mexico, and rural areas of Chile display significantly higher and more simultaneous deprivations than urban areas of Argentina, Chile and Uruguay. In all countries, deprivation in access to proper sanitation and education of the household head are the highest contributors to overall multidimensional poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The approach was also implemented by the World Bank in other developing regions of the world since 1978 (Streeten et al. 1981).

Indeed, a growing number of social policy initiatives in Latin America are based on multidimensional indicators—for instance, for the identification of beneficiaries of the Progresa/Oportunidades conditional cash transfer program in Mexico and in the SISBEN targeting system in Colombia.

Both Argentina and Uruguay are highly urbanized countries, with an urban population share of 87 and 92 % correspondingly. In the case of Argentina, the survey currently covers about 61 % of the total population in the country. However, over the years, the survey has progressively incorporated urban areas. For comparability reasons we work with the 15 urban agglomerations that were included since 1992. These urban areas represent 45.7 % of the total country population. The survey in Uruguay covers about 80 % of the total country population.

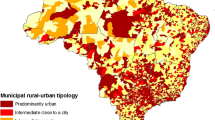

In Chile it corresponds to localities of less than 1,000 people or with 1,000–2,000 people, of which most perform primary activities. In Mexico it refers to localities of less than 2,500 people. In Brazil, rural areas are not defined according to population size but rather they are all those not defined as urban agglomerations by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. In El Salvador, rural areas are all those outside the limits of municipalities heads, which are populated centres where the administration of the municipality is located. Again, this definition does not refer to any particular population size.

UNCTAD is the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, and UNEP is the United Nations Environment Programme.

For most countries in the region there are UBN estimates with the 1980, 1990 and 2000 censuses.

For example, water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions reduce diarrhoeal disease on average by between one-quarter and one-third. According to the WHO, diarrhoea causes 2.2 million deaths every year mostly among children under the age of five. Safe water is estimated to reduce the median infection rate of trachoma by 25 %. It has also been found that well designed water and sanitation interventions reduce by 77 % the median infection rate of schistosomiasis. Finally, cholera can also be prevented with access to safe drinking water (WHO and UNICEF 2000).

Cruces and Gasparini (2008) illustrate these inclusion and exclusion effects by studying the targeting of cash transfer programs based on a combination of income and other UBN-related indicators.

This ‘hybrid method’ can be criticized for potential double-counting, arguing that dimensions that may have been considered in the basic consumption basket used to determine the poverty line are included again as a separate indicator. However, in this dataset, the Spearman correlations between income and the other different indicators are relatively low (not exceeding 0.5 in any case) and decrease over time, suggesting that a multidimensional approach does indeed incorporate new elements to poverty analysis. Table A.2 in the Appendix reports these correlations.

Note that the $2.15 per capita per day line was usually referred as $2 per day line and was set as twice the value of the so called $1 per day line (actually 1993 PPP $1.08).This poverty line is prior to the latest revision by the World Bank (Ravallion et al. 2009), which replaced the 1993 PPP $1.08 a day line with the 2005 PPP $1.25 a day line, and the 1993 PPP $2.15 a day line with the 2005 PPP $2.00 a day line. For further details on this change, see World Bank (2008).

Note that this is also the approach taken in the Multidimensional Poverty Index developed by Alkire and Santos (2010) for the 2010 Human Development Report.

On the meaning of dimension weights in multidimensional indices of well-being and deprivation and alternative approaches to setting them, see Decancq and Lugo (2012).

Note however that the distinction is not clear. As argued above, sanitation and water can be understood as proxies for health, belonging to a different dimension.

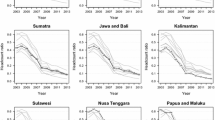

Indeed, with equal weights for example, the multidimensional headcount ratio with k = 2 in 2006 is 10 % in Argentina, 8 % in Chile and 6 % in Uruguay, whereas the average deprivation share is about 0.38 in the three countries (2.3 indicators). This can be verified in panel (a) of Fig. 2.

For example, when VP weights are used and the cut-off is k = 1, someone living in a household deprived either in income or having children who do not go to school would be considered poor. However, someone with a household head with a low level of education and without access to sanitation would not be identified as poor, since the sum of weights is lower than one.

Note that the BC indices with θ = 0 coincide with the multidimensional headcount ratio for k = 1 already reported in Fig. 3. When VP weights are used, the estimates with each combination of (θ, α) are lower. This is because weight is shifted from the dichotomous variables to the two continuous variables that receive the highest weights (income and children in school), which are not the ones with the highest deprivation rates.

References

Alkire, S. (2002). Dimensions of human development. World Development, 30(2), 181–205.

Alkire, S. (2008). Choosing dimensions: The capability approach and multidimensional poverty. In N. Kakwani & J. Silber (Eds.), The many dimensions of poverty (pp. 89–119). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. E. (2007). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. OPHI working paper 07, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. E. (2011). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7–8), 476–487.

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2009). Poverty and inequality measurement. In S. Deneulin & L. Shahani (Eds.), An introduction to the human development and capability approach (pp. 121–161). London: Earthscan.

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2010). Acute multidimensional poverty: A new index for developing countries. OPHI working paper no. 38. Oxford: Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative.

Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2013). A multidimensional approach: Poverty measurement and beyond. Introduction to the special issue. Social indicators research. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0257-3.

Altimir, O. (1982). The extent of poverty in Latin America. World Bank staff working papers no. 522. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Amarante, V., Arim, R., & Vigorito, A. (2010). Multidimensional poverty among children in Uruguay. Research on economic inequality Vol. 18: Studies in applied welfare analysis: Papers from the third ECINEQ meeting (pp. 31–253). Bingley: Emerald.

Arim, R., & Vigorito, A. (2007). Un análisis multidimensional de la pobreza en Uruguay. 1991–2005, Serie Documentos de Trabajo DT 10/06. Uruguay: Instituto de Economía, Universidad de la República.

Atkinson, A., Cantillon, B., Marlier, E., & Nolan, B. (2002). Social indicators—The EU and social inclusion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ballon, P., & Krishnakumar, J. (2008). Estimating basic capabilities: A structural equation model applied to Bolivia. World Development, 36(6), 992–1010.

Beccaria, L., & Minujin, A. (1985). Metodos Alternativos para Medir la Evolucion del Tamaño de la Pobreza, Documento de Trabajo No 6. Buenos Aires: INDEC.

Betti, G., Cheli, B., Lemmi, A., & Verma, V. (2007). The fuzzy approach to multidimensional poverty: The case of Italy in the 1990s. In N. Kakwani & J. Silber (Eds.), Quantitative approaches to multidimensional poverty measurement (pp. 30–48). Palgrave Macmillan.

Boltvinik, J. (1990). Pobreza y necesidades básicas, conceptos y métodos de medición. Proyecto Regional para la Superacion de la Pobreza. Caracas: PNUD.

Bourguignon, F., & Chakravarty, S. (2003). The measurement of multidimensional poverty. Journal of Economic Inequality, 1(1), 25–49.

Calvo, C. (2008). Vulnerability to mulidmensional poverty. World Development, 36, 1011–1020.

CEDLAS. (2009). A guide to the SEDLAC-socio-economic database for Latin America and the Caribbean. Centro de Estudios Distributivos, Laborales y Sociales, Universidad Nacional de La Plata. http://www.cedlas.org/sedlac.

CEDLAS & World Bank. (2009). Socio-economic database for Latin America and the Caribbean (SEDLAC). http://www.cedlas.org/sedlac.

Chiappero Martinetti, E. (2000). A multi-dimensional assessment of well-being based on Sen’s functioning theory. Rivista Internationale di Scienzie Sociali, CVIII, 207–231.

Conconi, A., & Ham, A. (2007). Pobreza multidimensional relativa: Una aplicación a la Argentina. Documento de trabajo CEDLAS N. 57. Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Argentina: CEDLAS.

Cruces, G., & Gasparini, L. (2008). Programas sociales en Argentina: Alternativas para la ampliación de la cobertura. Documento de trabajo CEDLAS N. 77. Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina: CEDLAS.

Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation. (1976). What now—another development. The 1975 report on development and international cooperation. Sweden: Motala Grafiska.

Decancq, K., & Lugo, M. A. (2012). Weights in multidimensional indices of well-being: An overview. Econometrics Review, 32(1), 7–34.

Duclos, J.-Y., Sahn, D., & Younger, S. (2006). Robust multidimensional poverty comparisons. The Economic Journal, 116(514), 943–968.

Feres, J. C., & Mancero, X. (2001). El método de las necesidades básicas insatisfechas (NBI) y sus aplicaciones a América Latina, Series Estudios Estadísticos y Prospectivos. Santiago, Chile: CEPAL.

Gasparini, L., Cruces, G., & Tornarolli, L. (2008). A turning point? Recent developments on inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean. Nacional de La Plata, Argentina: CEDLAS.

Herrera, A. O., Scolnik, H. D., Chichilnisky, G., Gallopin, G. C., et al. (1976). Catastrophe or new Society? A Latin America world model. Ottawa: IDRC.

International Labour Organisation. (1976). Meeting basic needs: Strategies for eradicating mass poverty and unemployment: Conclusions of the World Employment Conference. Geneva: ILO.

Kaztman, R. (1989). La heterogeneidad de la pobreza. El caso de Montevideo. Revista de la CEPAL, 37, 141–152.

Lemmi, A., Betti, G. (2006). Fuzzy set approach to multidimensional poverty measurement. Economic studies in inequality, social exclusion and well-being. New York: Springer.

López-Calva, L. F., & Ortiz-Juárez, E. (2009). Medición multidimensional de la pobreza en México: Significancia estadística en la inclusión de dimensiones no monetarias. Estudios Económicos, special issue, 3–33.

López-Calva, L. F., & Rodríguez-Chamussy, L. (2005). Muchos rostros, un solo espejo: Restricciones para la medición multidimensional de la pobreza en México. In M. Székely (Ed.), Números que mueven al mundo: La medición de la pobreza en México. Mexico City: Miguel Ángel Porrúa.

Paes de Barros, R., De Carvalho, M., & Franco, S. (2006). Pobreza multidimensional no Brasil. Texto para discussão No. 1227. Brazil: IPEA.

PNUD. (2009) Informe sobre Desarrollo Humano para Mercosur 2009–2010 “Innovar para incluir: jóvenes y desarrollo humano”. Buenos Aires.

Ravallion, M., Chen, S., & Sangraula, P. (2009). Dollar a day revisited. The World Bank Economic Review, 23, 163–184.

Santos, M., Lugo, M., Lopez Calva, L. Cruces, G., & Battiston, D. (2010). Refining the basic needs approach: A multidimensional analysis of poverty in Latin America. Research on economic inequality Vol. 18: Studies in applied welfare analysis: Papers from the third ECINEQ meeting (pp. 1–29). Bingley: Emerald.

Sen, A. (1992). Inequality re-examined. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sen, A. K. K. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. London: Allen Lane.

Stewart, F. (1980). Country experience in providing for basic needs. In P. Streeten, F. Stewart, S. J. Burki, A. Berg, et al. (Eds.), Poverty and basic needs. World Bank working paper 33061 (pp. 9–12). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Streeten, P., Burki, J. S., Haq, M. U., Hicks, N., & Stewart, F. (1981). First things first: Meeting basic human needs in developing countries. New York: Oxford University Press.

Székely, M. (2003). Lo que dicen los pobres. Cuadernos de desarrollo humano No. 13. México: Secretaría de Desarrollo Social.

The Cocoyoc Declaration. (1974). Adopted by participants in the UNEP/UNCTAD symposium on patterns of resource use, environment and development strategies. International Organization, 29(3), 893–901.

World Health Organization (WHO) & United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2000). Global Water Supply and Sanitation Assessment 2000 Report.

World Bank. (2008). World Development Indicators. Poverty Data. A Supplement to World Development Indicators. Washington DC: World Bank.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the United Nations Development Programme Regional Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford. Santos thanks ANPCyT-PICT 1888 for research support. The authors are thankful for comments provided by Andrés Ham, by participants of OPHI Seminars Series in Trinity Term 2009, and of the third Meeting of the Society for the Study of Economic Inequality (ECINEQ), Buenos Aires, 21–23 July, 2009. The authors are also grateful for suggestions from two anonymous referees and thank Felix Stein for research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The paper was written while Lopez Calva was at the Regional Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), New York, USA.

The paper was written while Maria Ana Lugo was at the Economics Department and at the Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI), Queen Elizabeth House (QEH), Oxford Department of International Development, University of Oxford, UK.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Battiston, D., Cruces, G., Lopez-Calva, L.F. et al. Income and Beyond: Multidimensional Poverty in Six Latin American Countries. Soc Indic Res 112, 291–314 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0249-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0249-3